by Sugen Ramiah

It was the ninth day of the seventh lunar month, and I have been busy documenting rituals and customary practices of the Hungry Ghost Festival. Every temple or ‘sintua’ (a group of devotees with no temple and who gather in a place which host the deity statues and censers) has its own designated date, to perform cleansing rituals for the wandering souls. Released into the human realm, these are souls who have no one to remember them and assuage their suffering by making them offerings. This year I was fortunate to have been invited by the members of ‘Xuan Jiang Dian’ (Tortoise Hill) temple, to observe their seventh month memorial service.

Due to lack of space at the temple’s premises, a temporary tentage was set up in an open car park located in Bukit Merah View. Preparatory rituals had begun earlier that day, performed by visiting priests from China. These rituals were to cleanse and protect the holding ground from negative elements.

Members of the temple and fellow Brownies(the volunteers at Bukit Brown) gathered in the late afternoon and were greeted by the thunderous sounds of the temple’s newly formed gongguan (percussion) troupe.

We left the premises just before 7pm to gather lost souls from two different locations. The first was at the East Coast Park beach, followed by Bukit Brown cemetery. When we reached our first destination, a temporary altar was set up and chanting accompanied by the sounds of cymbals and drums began.

The Chinese believe that once a soul departs from its mortal body, it loses its direction. Lanterns help to light the way for the soul. Since they were going to call on many souls, a two metre long paper inscription fixed to an extended bamboo branch was used; It was to ensure maximum visibility for the souls. As the priests sang, the branch was flagged rhythmically according to the melody. Once the lanterns returned to ashore, offerings of paper money were burnt and the gongguan troupe received the wandering guests with their music.

The altar was then dismantled and we proceeded to our next destination, the Bukit Brown Cemetery. As the convoy led by the gongguan transported on a brightly decorated truck, turned into the Sime Road, the gleaming LED lights of the truck, glowed in the poorly lit road. The deafening clangs and gongs must have awakened the neighbouring residents including the residents of Bukit Brown. As the truck drove past the cemetery gates, the buses stopped at the T-junction of Sime and Kheam Hock Roads with Jalan Halwa. A few of us alighted and ran through the cemetery gates with heightened anticipation.

As we entered, the vision of a trail of lighted candles against the backdrop of the night sky, took our breathe away.

The temporary altar was once more erected, but this time they placed a special tablet dedicated to the lost souls of Bukit Brown. As the priests chanted and called upon the countless souls, I was moved by their rituals. Unlike the powers that be who have abandoned them, I was glad there were still Samaritans who remembered them.

These are the souls of ancestors who have been long forgotten, infants and the unsung heroes who died tragically during the war. To give them temporary lodging, meals to feed their hunger and prayers to purify their weary souls, is by far the greatest act of kindness and filial piety.

As the priests circled the roundabout, there was a sense of closure in the air, as though the souls have found the light. To conclude the rituals, paper money was burnt as an offering and the gongguan troupe signaled the close of the ceremony at Bukit Brown.

It was time to return to Bukit Merah for the concluding rites. We alighted along the main road, about five hundred metres away from the holding ground and lined up for a procession. The gongguan troupe on the glittering LED flower truck led the way. Following immediately behind, the tablet dedicated to the wandering souls, the lanterns carried by devotees and participants holding joss sticks. This drew the attention of the residents in the neighbourhood and the people eating at the hawker centre.

As we marched triumphantly down the street with our “guests”, we felt that we had accomplished something meaningful: We had found and acknowledged in our hearts, the forgotten souls of Bukit Brown.

Sugen Ramiah a teacher by training, has been observing and documenting Chinese festivals and rituals conducted by temples for the past one and half years.

Every year on the 1st day of the 7th month lunar calender, the Chinese believe the gates of hell are opened, and the spirits are released to the earthly realm. Liew Kai Khiun shares his reflections of the rituals conducted at Bukit Brown Cemetery for the wandering souls.

Remembering the Forgotten and Forsaken

I had the opportunity to participate in one of the rituals for the lunar 7th Month festival at Bukit Brown Cemetery. Known as the “Hungry Ghost Festival”, this is a time where souls are released from hell for a month to roam the human realm. Although considered an inauspicious month where no weddings and property transactions takes place, it is actually a time for the living to remember the forgotten dead. Even the practice can be seen to be feudal, it is actually a spiritual extension of acts of charity to the wandering and homeless souls.

Long before it was known to the larger public, devotees from temples have quietly organized rituals to commemorate the nameless souls from the pauper graves of Bukit Brown Cemetery. While I have participated in Chinese folk religious rituals since I was a kid (particularly during military service), being self-taught in Karl Marx, I am not a very religious person. But, since the finalization of plans to run a mega expressway through Bukit Brown Cemetery by the end of the year, I felt the need to apologize and beg for forgiveness for not doing enough to stop this soulless project of the living from penetrating into this soulful place of the dead.

The night with this particularly group of devotees and the priest has been my most soulful and spiritual experience in Bukit Brown Cemetery. As the priest blessed my car before I exit the premise in the wee hours of the morning, I have never felt so tranquil and at ease driving home. Although these activities are done away from the public limelight, I feel the need to pen my thoughts here to clear common misconceptions and prejudices of such practices.

I am also truly humbled by their continued efforts without any intention of public recognition whatsoever. For those who have been forgotten and forsaken in life, it is rituals and activities like such that we try to remember them in their after-life.

It is not the road, but the rich cultural and ecological diversity that gives Singapore a soul.

Co-existence of Culture and Nature: This is a wonderful moment where smoke from the incense emerges amidst the hanging roots and leaves

Footnote: Unlike in HDB estates, these devotees do clean up and pack up after the rituals end

For more from Kai Khiun’s album, please click here

Since the news of the redevelopment of Bidadari Cemetery in the late 1990s, Kai Khiun has been involved in advocacy of Singapore’s built and natural heritage. As an academic, he has also been involved in the research and documentation of socio-cultural and historical issues in East and Southeast Asia, and has published some works recently on the use of the social media by conservationists in Singapore.

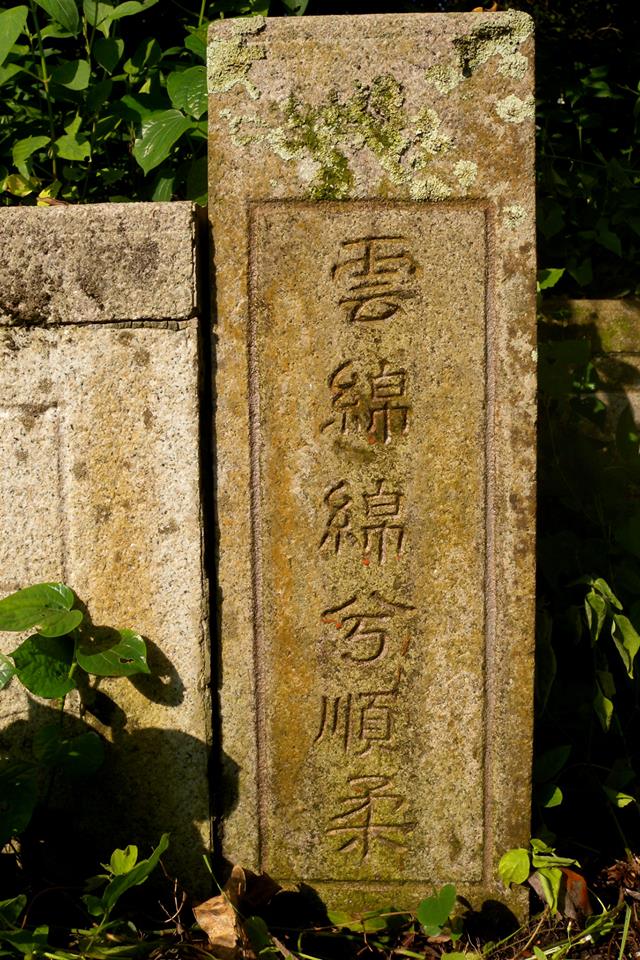

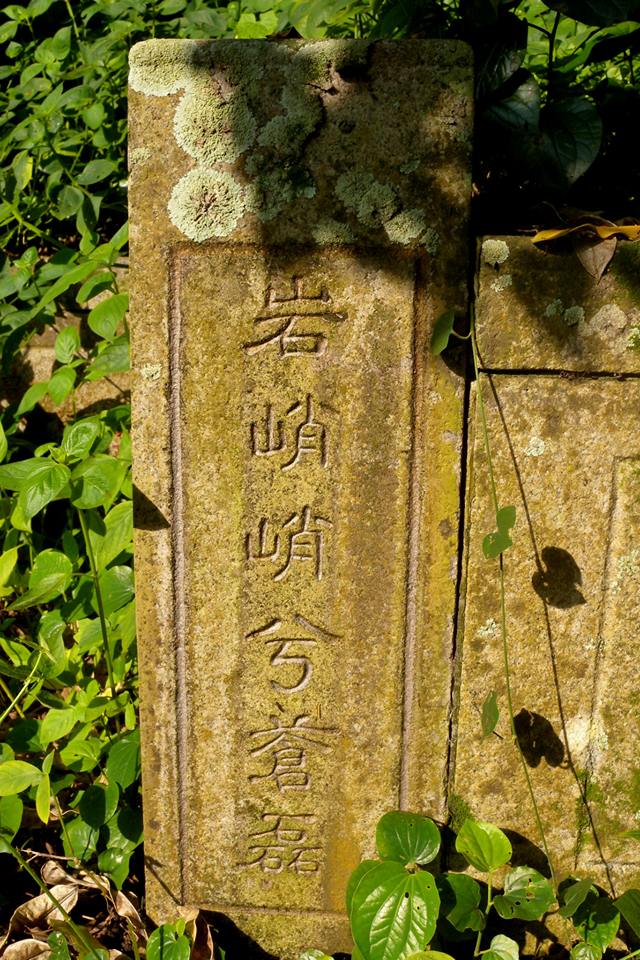

At Bukit Brown, one often finds couplets on the “pillars” of the tombs. They embed auspicious meanings and also tributes to the departed. The above couplets reads:

雲绵绵兮柔顺

岩峭峭兮蒼磊

Translated by Tay Hung Yong from the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery FB group, t reads

“Soft and gentle are the endless clouds;

The rock stands solid for eternity.”

Hung Yong says, “It signifies ever lasting love for the decease.”

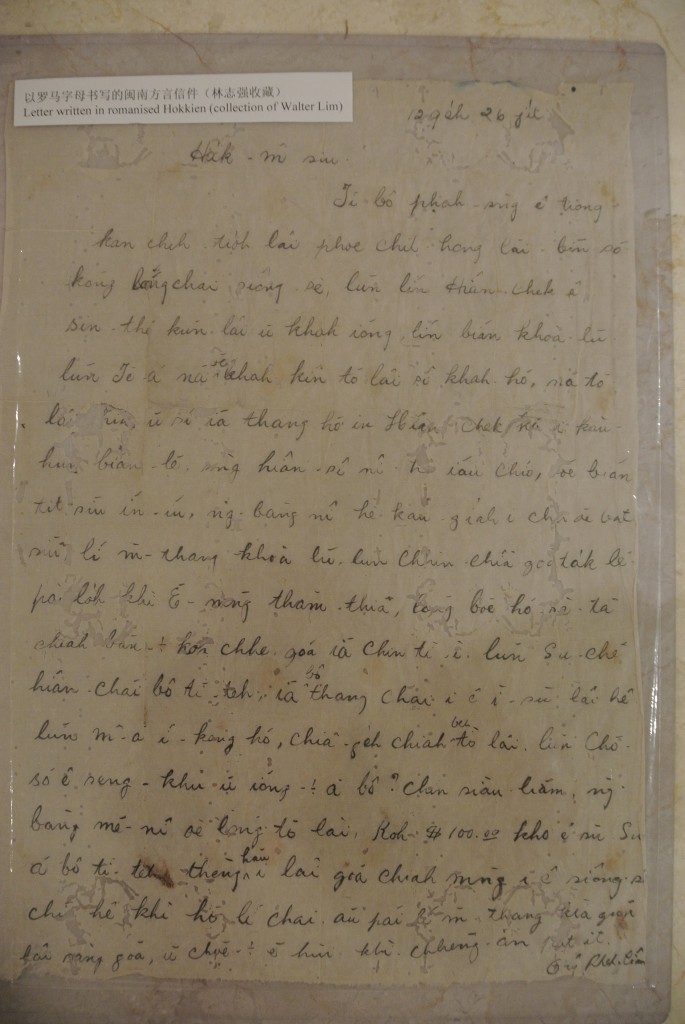

A letter in Romanized Hokkien , or Pe̍h-ōe-jī as it is known, on display at the exhibition Our Roots, Our Future, piqued the interest of many. But no one could fully decipher its meaning. A challenge was sent out to the Singapore Heritage Bukit Brown Cemetery FB group. It caught the eye of 卓育興 Yu Hsing Jow who is a Taiwanese living in Singapore researching on Hokkien culture here. He alerted an expert from Xiamen, Lim Kian Hui. who was able to help decipher and translate the the letter.

卓育興Yu Hsing Jow translated it into Mandarin, and from Mandarin, we finally have an almost full English translation by Brownie Ang Yik Han. It reads:

Hàk-ḿ: (the letter is addressed to a woman named Hak)

I received a letter out of the blue which covered many details. Your uncle’s health is better, please don’t worry. If his son can return it will be better, as your uncle can teach and encourage him. He is young and susceptible to temptations, hopefully he will be wiser when he is older, please don’t worry. As for the relatives, they are not in good condition when I visit them in Amoy every week, but I am not too concerned. Your senior is not here now, I have no wish to inform her as well, but she will be back in the first lunar month. How are the sisters-in-law? They are so young, I wish they can be back every year. Also, there is the matter of the $100. The teacher is not in school, I will enquire about him later. As for this mark (unclear what this is) , please do not send it to me in the future, it takes a lot of effort. Take care.

The content is representative of letters that would have been exchanged by families and friends separated in the Chinese Diaspora. It covers in one page an update on financial matters and the domestic situation at home, but the tone of the letter also expresses care, concern and reassurance.

Here is the letter transcribed in Pe̍h-ōe-jī by 卓育興 Yu Hsing Jow

Ha̍k-ḿ siu

Jí-bô phah-sǹg ê tiong-kan, chiap-tio̍h lâi phoe chit hong, lāi-bīn sō kóng long chai siông-sè . lūn lín hiân-chek ê sin-khu, kūn lāi ū khah iōng, lín bián khoà-lū. lūn jī á nā-sī khah kín tò-lâi pó khah hó. Nā tò-lâi chia, ū sî iā thang hō͘ in hiân-chek khah I kàu-hùn, bián-lē. sǹg hiân-sî nî-hè iáu chió, bē bián tit-siū ín-iń, ng-bāng nî-hè kàu gia̍h i chiū ē bat siūⁿ . lí m̄-thang khoà-lū. lūn chhin-chiâⁿ goá ta̍k lé-pài lo̍h khì Ē-Mn̄g thām thiā, long boē hó-sè. Tā-chiah chia bān-bān koh chhōe, goá iā chin tì-ì . lūn su-chē hiân-chai bô tī the, iā thang chai ié ī-sū. Lái heⁿ lun̄ mā ái kóng hó, chiaⁿ-ge̍h chiah beh tò-lâi. Lūn chō sō ê seng-khu ū ióng-ióng á-bô. Chin siàu-liân ǹg-bāng mê-nî ē long tò-lâi, koh $100.00 kho ě sū. Suá bô ti-teh thēng hāu-lâi,góa chiah mn̄g I ê siông-sè, chit ê kì-hō,lí chai āu-pái m̄-thang kià kòe lâi sàng góa, ū chōe chōe êhùi khì. Chhéng an put it.

Ông pheh lîm

Many thanks to 卓育興 Yu Hsing Jow for the transcription and his time spent in helping to translate the letter. He has since included the letter to the Wikipedia on Singaporean Hokkien

About the letter:

The Letter was donated to the exhibition Bukit Brown: Our Roots,Our Future, by a descendant of Tan Boon Hak, cousin of Tan Kah Kee)

The Wayang in the Tombs (2)

by Ang Yik Han

The Wayang in the Tombs 1 continues, as Yik Han unravels more iconic scenes from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and other popular stories.

“Temple of Sweet Dew” (Gan Lu Si – 甘露寺)

Zhou Yu, Sun Quan’s viceroy, wanted to lure Liu Bei over to the kingdom of Wu and then incarcerate him, on the pretext of marrying Sun Quan’s younger sister to him. Liu Bei’s advisor, Zhuge Liang, saw through this and ordered Zhao Yun, one of Liu Bei’s generals, to accompany him for protection. At the same time, he sent word to Sun Quan’s father-in-law to get Sun Quan’s mother along so that she can view her prospective son-in-law at the Temple of Sweet Dew. With the old lady around, Zhou Yu’s mischief came to naught and Liu Bei and his lady successfully got hitched.

Bowing man on left is Liu Bei, seated lady in the centre is Sun Quan’s mother, man on the right is probably Sun Quan’s father-in-law.

Editors note: An insight on how Yik Han deciphered this panel.

“The costumes especially the head dress are clues. If you look at what the man on the left is wearing, you can tell he is not just another official. For some tine I thought the figure in the middle is a male till I looked more closely at her headdress which is what you will expect a more senior lady of high social status to wear. Put these two together and you have a high ranking older male, probably some lord, paying respects to an old woman also of high social status. All the other identified panels from this tomb are based on the Three Kingdoms, and there is one famous part of the novel which has this setting, so that’s how I identified the scene. If you area Chinese opera fan, you may also recognise it easily.”

Here’s an animated excerpt from the opera

Lui Bei’s Farewell to Xu Shu

Compared to his warlord contemporaries, Liu Bei was handicapped by the lack of an able advisor. Fortunately for him, a brilliant strategist named Xu Shu joined him and helped him achieve some small victories. Just when things seemed to be going well for Liu Bei, his rival Cao Cao found out about this and he managed to get someone to send a forged letter to Xu Shu, purportedly from Xu Shu’s mother. The letter claimed she was in Cao Cao’s custody and her life was in danger unless Xu Shu abandon Liu Bei and join Cao Cao’s camp. The filial Xu Shu had no choice but to obey and the inevitable farewell came. On the day Xu Shu left, Liu Bei saw him off with his retainers and followed behind him for part of his journey. Upon reaching a forest, Liu Bei exclaimed “I want this forest to be cut down!” When his retainers asked him why, Liu Bei replied that this was because the trees blocked his view of the departing Xu Shu.

Here’s an opera you can view on the sending off.

The panels are from the tombs of the Teo Family located in Hill 2

The Third Madam teaches her son (三娘教子)

During the Ming Dynasty, there was a businessman by the name of Xue Guang who had a wife Mdm Zhang and two concubines, Mdm Liu (who bore him his only son Xue Yi) and Mdm Wang. Xue Guang conducted his business far from home. One day, he asked a man from his hometown to deliver five hundred taels of silver to his family. Instead of doing so, the man took the silver for himself and told the Xue family that Xue Guang had died. As they believed the report to be true and there were no news from Xue Guang, Mdm Zhang and Mdm Liu remarried after some time due to the family’s slide into poverty.

Only Mdm Wang chose to remain and take care of Xue Yi even though he was not her flesh and blood, together with an old servant Xue Bao. She weaved cloth to support Xue Yi through school. Xue Yi was however mocked by other children in school as the boy without a mother. Losing his temper, he took it out on Mdm Wang when he got home, saying that she had no right to punish him as she was not his mother. In fury, she slashed the cloth on her loom into two, signifying the serverance of their relationship, shocking Xue Yi and Xue Bao who hurriedly interceded on his young master’s behalf. Xue Yi came to his senses and promised to apply himself to his studies diligently, and even offered the cane to Mdm Wang to punish himself. In years to come, Xue Yi gained honours in the imperial examinations.

A movie based on the opera can be found here

The Wayang in the Tombs

by Ang Yik Han

(Popular tales performed in Chinese Wayang carved in iconic scenes on tomb panels.)

In the ” Romance of the Three Kingdoms” General Guan Yu is immortalised as the epitome of loyalty and righteousness. He played a significant role in the establishment of the state of Shu Han during the period of the Three Kingdoms.

Guan Yu took a poisoned arrow in his right arm when he was besieging the city of Fanzheng. Determined not to retreat, he called upon the services of the famed physician Hua Tuo to treat him on the battlefield. Hua Tuo saw that the poison had spread to Guan Yu’s bones and he had to operate on his arm and cleanse the poison by scrapping his bones. Undeterred, Guan Yu subjected himself to the ordeal, all the while sipping his wine and playing a game of chess. ( photo by Yik Han)

Legend? Embroidered truth? It does not matter, over the ages from at least the Ming Dynasty, the image of Guan Yu smiling and sipping his wine while Hua Tuo scrapped his arm bone has been a source of wonder and encouragement for many.

This tomb is located in Hill 2 and belongs to the Teo Family.

More tombs featuring Guan Yu, here

From Madam White Snake :

A panel possibly of the White Snake parting with her husband after he was taken in by the words of the monk Fa Hai. (photo Yik Han)

The White Snake and her companion the Green Snake (the two ladies in the boat) leading the creatures of the sea in an attempt to flood Jinshan Temple and rescue her husband Xu Xian (许宣) from the clutches of the monk Fa Hai (法海). (photo by Yik Han)

From Nezha conquers the Dragon King :

Nezha storming the palace of the Dragon King with his signature Qiankun ring in one hand, his spear in the other and riding on his “fire wind wheels”. The Dragon King flanked by his courtiers are seated on his throne on the right, a bumbling turtle is trying to resist Nezha, and on the left is a shellfish nymph. (photo Yik Han)

Nezha storming the Dragon King’s domain as the Dragon King riding on a magnificent dragon beats a hasty retreat covered by his underlings. The armed figure on the right may be Nezha’s father Li Jing (李靖), furious with the havoc created by his son (Photo Yik Han)

The panels can be seen at the tombs of Poh Cheng Tee and his wife, and mother, in Hill 1, stake numbers 1017 – 1019. Exhumation of staked tombs in the way of the 8 lane highway is expected to begin after April 15th

Four Appointments (四聘)

by Ang Yik Han

Yet another set of four popular stories from Chinese history, this time found at the double tomb of Chew Joo Chiat and his wife, the subjects of the “Four Appointments” are two great rulers and two renowned officials who assisted their masters ably in establishing their kingdoms.

1 Yao Appoints Shun (尧聘舜)

Yao (尧), a great ruler of the Xia Dynasty (夏朝) the origins of which have been lost in time, was troubled. His son was not fit to assume the mantle of leadership and the whole land knows it. He had no choice but to hand over to someone from outside the family but a suitable candidate had to be sought. Word came to his ear of a filial young man, Shun (舜), a commoner who had lost his mother at a young age. His father’s already bad temper became worse after this and after he remarried, his affection turned from him to his new son. Shun’s stepmother and his stepbrother also treated him badly. Despite this, he was steadfast in his obedience to his parents. His filial piety was such that one day, the celestial courts sent an elephant to help him till the soil and birds to weed his fields. Yao judged that Shun was the best candidate for the position after he met him and even married his two daughters to him. Shun did not fail to disappoint and became another great ruler. The motif of the elephant in Chinese art has since been associated with peace and prosperity in the land on this account.

Shun sits by his fields as the elephant and what looks like a well-fed bird helps him out with his farming. Yao approaches from the left. (photo Yik Han)

2 Shun Appoints Yu (舜聘禹)

During Shun’s (舜) reign, floods were a constant scourge for the people. He appointed Gun, father of Yu (禹) to tackle this problem. Gun’s efforts were ultimately unsuccessful and Yu was appointed in his place. Unlike his father who tried to stem the flood waters with dams and embankments and failed, Yu created tributaries to disperse the waters. He was so dedicated to his work that he was supposed to have traveled around the land continuously for ten years. Even though he passed by his house 3 times, he did not stop to visit his family and missed his child’s birth and growing years. When he eventually succeeded in taming the waters, his knowledge of the lay of the land was unsurpassed. Coupled with his well-known concern for the people’s welfare, none was thought more eligible to take over as Shun as ruler. Till today, he is known as the “Great Yu” (大禹) in remembrance of his deeds.

Yu building a brick wall in preparation to channel the flood waters as Shun arrives on the scene. (photo Yik Han)

3 Shang (Cheng) Tang Appoints Yi Yin (商汤聘伊尹)

The last ruler of the Xia Dynasty (夏朝) was a tyrant notorious for his wanton cruelty and excesses. He paid no heed to governmental matters, which was to be his undoing. One of his vassals, Cheng Tang (成汤) saw the opportunity to advance himself, quietly built up his strength and bringing men of talent into his fold. Hearing about Yi Yin (伊尹), he visited and met him with his buffalo. Yi Yin rebuffed his invitation however, stating that he had no wish to become an official and that he had no abilities to speak of. Cheng Tang had no choice but to leave. Soon after, however, Yi Yin was brought to his attention again, such was his reputation. It was only on Cheng Tang’s third visit that he succeed in convincing Yi Yin to cast his lot with him. With his help, Cheng Tang overthrew the Xia and became the first king of the Shang Dynasty (商朝). As for Yi Yin, he is remembered as a great politician, strategist, philosopher as well as a good cook; he was adopted as one of the patron deities of cooks in China.

Yi Yin pulling his buffalo behind him as Cheng Tang respectfully makes clear his intention in meeting him. (photo Yik Han)

4 King Wen Appoints Tai Gong (文王聘太公)

During the Shang Dynasty (商朝), the Duke of the West, Ji Chang (姬昌), traveled around his realm to seek men of talent who could help him administer his domain. One day, on the banks of the River Wei, he saw an old man who was fishing with no bait, using only a bare fish hook which was straight instead of curved. When asked why he did this, the old man replied that those who were willing would be hooked voluntarily. Realising he had met an exceptional person, the Duke invited the old man into his carriage and personally pulled him along for eight hundred steps. The old man, Jiang Ziya (姜子牙), was to become the Duke’s trusted advisor and his kingdom’s chancellor, helping his son overthrow the tyrannical rule of the Shang Dynasty and establish the Zhou Dynasty (周朝). Ji Chang was given the posthumous title of King Wen (文王) after his son’s success and his able advisor was appointed as the Grand Duke (太公). This story forms part of the “Investiture of Deities” (封神演义), a fictionalised account of the Zhou’s triumph over the Shang replete with supernatural elements which has been part of popular literature and performance arts for centuries.

The Duke of the West on his way to visit the old man who waits for fish which cast themselves willingly on his hook. (photo Yik Han)

A common thread runs through the four stories: in their search for men of ability and virtue to help administer the country, rulers have to humble themselves and seek far and wide. The stories are a reminder of the respect that society is supposed to accord to the ones who have both the talent and heart to assume the mantle of government.

The Dragon King, The Emperor and a New Wife….

The most spectacular cluster of tombs at Bukit Brown belonging to Ong Sam Leong and family is resplendent with carved panels which depict stories from epic Chinese classics.

Ang Yik Han shares 2 panels of a story in the Chinese classic “Journey to the West”

Panel 1 from:

“After touring the underworld, the spirit of Emperor Taizong returns”

游地府太宗还魂

Underworld official adds 2 strokes to character as Emperor flanked by 2 companions look on (photo Yik Han)

Background: One of the dragon kings ran afoul of celestial law and was sentenced to be executed by an official at the Tang court. The desperate dragon turned to the then Emperor, Li Shiming (李世民), and beseeches him not to allow the official to go to sleep as that was the time the deed was supposed to be done. The Emperor agreed to help and promptly summoned the official to play chess overnight with him. During the game however, the official dozed off and in that short interval his spirit went off and slew the dragon king.

进瓜果刘全续配

Old House at Ang Siang Hill

by Arthur Yap

an unusual house this is

dreams are here before you sleep

tread softly

into the three-storeyed gloom

sit gently

on the straits born furniture

imported from china

speak quietly

to the contemporary occupants

they are not afraid of you

waiting for you to go

before they dislocate your intentions

so what if this is

your grandfather’s house

his ghost doesn’t live here anymore

your family past is

superannuated grim

which increases with time

otherwise nothing adds or subtract

the bricks and tiles

untill re-development

which will greatly change

this house-that-was

dozens of it along the street

the next and the next as well

nothing much will be missed

eyes not tradition tell you this

an extract from Thow Xin Wei who writes of the poet Arthur Yap’s work….

In “old house at ann siang hill”, a similar voice seems to suggest that even tradition is expendable in the pursuit of progress:

so what if this is

your grandfather’s house

his ghost doesn’t live here anymore

your family past is

superannuated grim

which increases with time

otherwise nothing adds or subtract

the bricks and tiles

untill re-development

which will greatly change

this house-that-was

dozens of it along the street

the next and the next as well

nothing much will be missed

eyes not tradition tell you this

In contrast to the opening of the poem, the viewpoint has shifted to that of the civil servant, with the casual disdain for the past, the calculative dismissal, and the firm conviction that “re-development” and change will mean progress; to hold on to the past is merely nostalgic sentiment, an old fashioned belief in “ghosts” that is not congruent with the rapidly modernising social and physical landscape of Singapore.

Interactions between those in authority and those subject to it also feature in Yap’s poetry. In “an afternoon nap”, an “ambitious mother… proclaiming her goodness”, punishes her son for his mediocre grades, while the “embittered boy” proclaims his “bewilderment” and berates her for her “expensive taste for education”. Both proclaim the other’s “wrongs”. It is tempting to read this poem as a metaphor for the relationship between government and citizens in Singapore, especially given the paternalistic character of a government which institutes policies regarding its citizens’ child bearing, hygiene and courtesy habits.

The Origins, Traditions and Beliefs of what today has become popularly known as “The Hungry Ghost Festival”

by Victor Yue

Between the ancient Chinese characters and the modern English vocabulary, there seems to be a big mis-match as to what the festival is about. But for ease of communication, some terms that seem to be closest in translation would it seems, have to do. In some cases, such as events, more exciting phrases were coined in Chinese and explains I believe how we have arrived at the name The Hungry Ghost Festival.

The Origins

It is said that although the 7th Month event is an age old tradition and custom from ancient times marked during the 7th lunar month, the term “Gui Jie” meaning Ghost Festival did not appear until the Ming Dynasty. I am curious as to when the word “Hungry” was added into the Ghost Festival, making it the Hungry Ghost Festival. Indeed this additional adjective does much to fire up the imagination of the more impressionable young and those unfamiliar with the 7th Month event.

Older Chinese, simply call it Chit Gue (7th month in Hokkien), Por Tor (Pudu in Mandarin) or Tiong Guan Huay (Zhong Yuan Jie) which is probably more official as these are the words used in the posters and banners put up during this time.

As with most age old traditions, it’s difficult to separate the practice, beliefs and the myths. We tend to embrace them together and it becomes a colourful, cultural potpourri

How is it “celebrated”?

The 7th Month in Singapore means different things to different people. To believers and those who have “the third eye”, it is a month when the entities of the nether world come a calling. “Don’t go out late, Don’t go swimming” would be the warning from Grandma. The grandchildren would dutifully say “yes” and do exactly the opposite! And should anything untoward happen, Grandma would say “I told you so!” and follow up with making reparations to ask the “invisible” for forgiveness.

For the Hokkiens and Teochews (and probably for other dialect groups as well), on the first night of the 7th month, they would be lining up candles and joss-sticks to “welcome” the visitors (who might include their ancestors) offering them food and burning joss-papers (money). They do the same on the last day of the 7th month to send them off. In between, on the 15th day, they would also d0 another similar round of offerings. For the Cantonese, I understand that they do it on the 14th night of the 7th month.

A few days before the arrival of the 7th month, the organisers of the neighbourhood’s 7th Month prayers – officially called “Celebrating Zhong Yuan Jie” – will set up make-shift altar tables at a suitable place, usually close to a lift landing or a corner of an HDB block Some HDB block or blocks may have more than one group of Zhong Yuan Jie organisers. Most of these organisers would have continued since the days when the residents were from a different neighbourhood. They tended to follow the migration of many of the residents from the old houses (kampong /pre-war homes) to their new homes in housing estates.

Back in the good ole days….

In the old days (circa 1950s), this event lasting between one and three days in any neighbourhood was one that the kids look forward to. Most families would subscribe to one of the Zhong Yuan Jie (or Por Tor in Hokkien) having paid a dollar a month. During the Por Tor, the organisers would have the goodies as offerings to the Por Tor Gong (the Tai Shi Ya or Da Shi Ya) before giving each subscribing household a pail of these goodies.

Apart from the 7 essentials (柴米油鹽醬醋茶- charcoal, rice, oil, salt, soya sauce, vinegar and tea – what’s needed in a typical kitchen of the old days ) there might be half a braised duck or chicken, something that was a luxury in the 50s for most families. There would also be an abundance of fruits – from Rambutans to Buah Langsat to Buah Duku.

For children, it was like carnival time. Street wayangs – about the only open air entertainment and free to boot of those times, would spring up. They were set up so skilfully within half a day using only mangrove poles tied together by soaked split rattan, and wooden planks for the flooring. I remember taking a stool from my house to “chope” (reserve) a place to watch. The afternoon show was from 2pm to 5 pm and evening from 8pm to midnight. Food was close at hand. Hawkers would encircle the wayang stage and even underneath the raised stage, selling food such as oh-jian (the traditional barnacles in fried sweet potato flour with eggs ), traditional desserts (offerings from red bean soups to sweet potatoes to tau suan and bubur telegu), fried kway teow, shellfish (cockles and siput) and much, much more. And when I was bored with the wayang I would take a turn at the games station and try my luck at tikam-tikam – just folded paper that for 5 centsa pick, you get a a shot at winning a prize of some cheap toy or sweets. I hardly ever won anything.

In the streets of Chinatown

In the Chinatown of old, each house would, in step with the organising communities for Por Tor, set up their altar tables outside their house to make offerings. As the majority of such houses had multiple tenants, the landlord would lead in organising the prayers. The narrow streets meant street wayangs were allocated specific dates for the Por Tor. One would be able to see the offerings from the beginning to the end of the street, with the triangular flags stuck into the food/fruits fluttering in the wind.

Sometimes, the community prayer ends up with a grand dinner where items are auctioned off and money raised – the collection of which could take up to a year – for the next Por Tor. The funds help to pay for not only the event but also the food baskets.

Enter the getai …

Getais came on the scene in theearly 60’s and overtook the wayangs in popularity (photo by Victor Yue)

Getai probably started in the 60s and quickly held the crowd captive. But long before their entry, some street wayangs had some of their actors/actresses singing before the opera started, as a warm up act, but it did not develop further. It took off probably following the hey day of the wildly popular Wang Sar and Yueh Fong. The duo took Singapore by storm and everyone knew the exclamation “Wah Lao”. During that time, there were also the Getai entertainment establishments where one could pay for entrance and get a drink to watch. The last one, similar to those in Taiwan, to my memory must the one at the former Wisma Atria, which I would go with my classmates each Chinese New Year eve.

In Chinese temples

In the Chinese Temples, the offering on the 15th of the 7th month was to Di Guan, one of the three Officials of the three realms – Tian (Heavens): celebrated on 15th of 1st Lunar Month), Di (Earth): celebrated on 15th of 7th Lunar Month and Shui (Water): celebrated on 15th of the 10th Lunar Month.

According to Taoist beliefs, praying to Di Guan is to ask for elimination of sins and debts. It is from this occasion of praying to the Di Guan or Di Yuan that the world of Zhong Yuan Jie came about.

Family….

For the family, 7th month is also a time for them to remember their ancestors. During the old days, each family, would have their ancestral altar at home. For the Hokkiens it would usually be placed next to another altar dedicated to Tua Pek Kong. For their most recently departed – a parent or grandparent – the family, usually the grandma or mother would prepare the offerings. The departed and the ancestors further down the line would be’invited” to come and partake of the offering. For us kids, it was also another occasion we waited for, for it meant that we could have more elaborate dishes that we would not get otherwise. Chinese New Year and 7th Month are the two major occasions that children look forward to and our poor parents would dread it as they would need to find money to cook up at least something worthy for their ancestors.

Today, many would have have moved the family ancestral tablets to the temples and so, offerings would be at the temples. Food offering’s also became simplified with fast food that could be the packed from chicken rice to Kentucky Fried Chicken.

7th Month represents a spectrum of Chinese culture, of beliefs, tradition and customs, with variations for different dialect groups, and in some instances also influenced by the practices from ancestral place of origin in China. We remember our ancestors; we think about the wandering souls (those whom the descendants have forgotten or who may no longer have living descendants); we seek pardons from the Official of the Earth Realm. This we do, to preserve our unique culture which also evolves with the times.

Victor Yue is Taoist and spends much of his time researching and documenting Chinese religious practices and rituals.

Here is a video he took on a auction on Pulau Ubin for the Hungry Ghost Festival

Here is another of Victor’s video on “Breaking Hell’s Gates” – a rare ritual conducted only once every 5 years at Peck San Theng Temple in Bishan

At Bukit Brown during the 7th month, tour groups also encounter evidence of rituals and offerings

Recent Comments