Bangsawan and the Bukit Brown connection. One of the earliest impresarios of traditional Malay Opera is buried in Bukit Brown and is highlighted in Group 2 Tour.

The Beginning of Bangsawan in Singapore

by Norman Cho

Before the advent of the television or the sound movies, theatrical performances were the few forms of entertainment available to the masses. One of which was the Bangsawan. The Bangsawan (Malay Opera) troupes consisted of professional Malay actors. The origins of the Bangsawan probably originated from the western plays. A small orchestra consisting of the violin, the accordion and local Malay percussion instruments such as the kompang, would normally accompany the stage-acts. Comedy and tragedy were the common genres. Stories which imbed morals were often told through these plays. While the plays were in Malay, the stories were adapted from legends and folklore from diverse origins such as Chinese, European, Hindi, Arabian and Malay. The classical Malay language was normally used. This would be a higher form of Malay that was used by the Malay Royal Courts, which was archaic.

The most renowned was the Star Opera Company (1909 – 1927) which was owned by the Peranakan brothers – K.H. Cheong (Cheong Koon Hong) and K.S. Cheong (Cheong Koon Seng) and was managed by their nephew Y.L. Tan (Tan Yew Lee). It was situated at Star Opera Hall – Theatre Royal, North Bridge Road. They accepted reservations through phone bookings as early as 1918. Tickets costs between $0.50 to $5. Star Opera was so popular that it received patronage from various Malay Royals like the Sulatan of Trengganu in 1910. Even the Europeans attended its 1914 production of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” in Malay.

Their star artiste was Khairudin, also popularly known as Tairu (Tairo). His name was synonymous with the Bangsawan. He was so sought-after that his performances were frequently sold-out. As with many movie stars of today, fame invited gossip. Magic charms had been suggested for his unwavering popularity. The nyonyas mesmerized by Tairu’s dashing good looks, literally threw their jewellery on stage after each performance – a diamond ring or a hurriedly unfasten kerosang intan (diamond brooch) being the commonest items. Flustered Babas forbade their wives from attending his performance. His career peaked during 1918 but he stopped performing for the Star Opera around 1924 to start and star in a very successful company called “Dean’s Opera” also at Theatre Royal, North Bridge Road. He had probably taken over the venue from Star Opera Company. By then he billed himself as Kairo Dean. Born in Hong Kong in 1890, he came to Singapore in 1900 and studied in Belilios Public School. He was not very good at his studies and worked as a handbill boy for Wang Kassim at the age of 14, earning 15 cents per day. He was talent spotted by its director Gulam Mydin and the rest is now history…

Over at Frankel Estate’s Opera Estate, streets were not only named after European Operas like Tosca, Aida or Figaro. Jalan Bangsawan, Jalan Khairuddin and Jalan Bintang Tiga of the Malay Opera world could also be found.

More on Bangsawan by Norman Cho here

Recently Bangsawan was revived by the Singapore River. Read Jerome Lim’s blog for more.

This article is adapted by Norman from

“an article first published in The Peranakan, Issue 3, 2011, pp. 3. Reproduced courtesy of The Peranakan Association, Singapore”

by Andrew Tan

In Bukit Brown Cemetery, an avenue, like prime real estate, connects Singapore’s prominent families—all inter-related, as these powerful cliques were linked by arranged marriages to perpetuate their wealth and influence through six generations, during 150 years of British rule (1819 to 1959).

Chronology

1819-1867 Beginnings

The earliest Asian elites in Singapore were comprador-kapitans from Malacca, who brokered with European (mainly British) companies, exclusive credit and arms deals. To procure native products for Europeans, compradors resourced from powerful clan headmen who controlled the supply of coolie labour, ships, and native products—crucial to entrepot success. Business partnerships were tied by arranged marriages between all families.

Family examples: Tan Tock Seng and his family network supplied and distributed manufactures for the British “country traders”; they also married influential relatives of the compradors and Kapitan Cina. Together, this was the first powerful clique in Singapore, which broadened (after Singapore’s cessation as entrepot of the opium-arms trade following British victory over Qing China) to include revenue farmers and labour contractors as their enterprises penetrated Southeast Asia.

1867-1900 Rise

From 1867, with Singapore a crown colony, the long established families recruited scholars and professionals as sons-in-law, to perpetuate their vested interests (e.g. tax-free “free trade” policies, opium farms, colonial intervention in tin-rich Malaya) through positions in the advisory board and councils at the municipal, rural and legislative level; appointments rotated among relatives (who advised the Governor on nominations) to ensure advantageous policy continuity.

The immediate decades after Suez Canal opened in 1869 diverted oceanic traffic through Singapore. To compete internationally, merchant families pooled their resources into joint-venture consortiums (in steamships); their offspring intermarried too. Ties between in-laws counted more than paper contracts.

Family examples: Notable Queen scholars (Lim Boon Keng, Song Ong Siang etc) and other top professionals were sons-in-law of well established merchant-shipping families like the Wee-Ho Hong-Lee group, as well as others who partnered in Straits Steamship.

1900-1941 Peak

Insatiable demand for World War One commodities (tin, rubber) produced the first multi-millionaires in Singapore: these nouveaux-riches—their heirs and heiresses were courted and charmed by Old Money. Merging New Money with Old gave birth to multifamily-owned conglomerates (e.g. OCBC, UOB, Straits Steamship) tying together banks, ships, plantations, factories and newspapers.

Large fortunes would aggrandize social ambition: Plutocrats usurped collective and consular institutions (e.g. Ngee Ann Kongsi, Chinese Chambers of Commerce), to connect with powerful Chinese warlords of lucrative market potential, offering to regimes funds for schools and humanitarian relief, using family-controlled newspaper editorials to galvanize mass involvement.

Ability to lead the Chinese masses into action was recognized by the British military; however, these plutocrats on war councils were relocated with their families to India just weeks before the Japanese Occupation.

Family examples: Families from shipping, commodities, revenue farming, and remittances, co-founded the conglomerates of OCBC and UOB, with ties to the burgeoning sectors like film and publishing, and family connections in politics.

1945-1959 Turning Point

In postwar Singapore, enriched by military contracts in the Cold War, scions used their wealth to contest for elected self-government, but the expanded, impoverished electorate rejected these “rich men’s parties” (Progressive Party and Democratic Party, whose members were related, merged into the Liberal Socialist Party), in favour of a new regime, the People’s Action Party (PAP).

Family examples: Contracts were monopolized by consortiums who subcontracted to each other. Chain of suppliers for the British military coalesced and expanded to retail giants.

1959 onwards Decline

Following Singapore’s independence under the PAP, the old elites diminished in economic influence: their once-predominant, century-old monopoly of colonial contracts was overshadowed by the growth of public state-sector industries in partnership with foreign multinationals. Attrition too, their vast landholdings compulsorily acquired by the state for redevelopment.

Their hereditary clan-leadership in communities has been subsumed by government departments that fund and run all neighbourhood activities and amenities. More than cultural and community centres, clans were once the centre of powerful labour unions. They once ran schools; but today, the Education Ministry syllabus and compulsory mandarin has created a generation disconnected with their dialect heritage, previously stressed in clan schools.

Arranged marriages and pedigrees became obsolete as post-war mass education broadened careers and widened choices in life partners. Also, professionalization broke down class barriers. The Women’s Charter in 1961 ended the quasi-feudal family structure.

As Singapore developed to become a middle class society, a new breed of technocrats allied with the PAP replaced the Old Establishment.

A multifamily tree, with 1000 people from 100 families, 6 generations interlinked in strategic alliances from the late 1700s to now, will be published in 2012. I shed light on the influential cliques (made up of powerful families) who dominated Singapore’s society and economy past two hundred years. Andrew Tan

Today, at precisely 12 pm, the sirens will sound all over Singapore to mark the darkest period in our nation’s history. 71 years ago on 15th February, the British surrendered to the Japanese after the devastating defeat of Singapore’s last strategic post of Bukit Chandu (Opium Hill.) Read Jerome Lim’s moving tribute to those who died valiantly to protect Singapore in that battle here.

a.t bukitbrown remembers the war by sharing the life and times of Tay Koh Yat, one of the war heroes buried in Bukit Brown.

Tay Koh Yat (1880 – 1957)

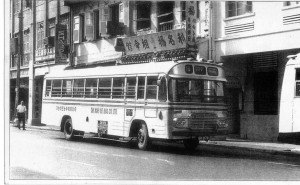

He was a pioneer in Singapore’s public transportation, but also a feisty patriot who started and led his own self defence force of 20,000 during the onset of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore in World War 2.

His grave located near the Bukit Brown cemetery gates is a fairly well maintained tomb and comes with benches, as if to offer a chance for people to gather and talk about his legendary deeds. The funeral cortege for Tay was grand with a reported 100 cars in attendance.

Tay was born in 1880 in Kinmen and came to Singapore when he was 22 years old. He started as a general worker in a trading company and was paid $2 a month. $1.50 was sent home to his family. Tay managed to survive on what was left because at that time, the meals, transport, housing was provided by his employer. So 50 cents was a luxury to be spend on aerated water or some porridge at hawker stalls. 2 bowls of porridge would cost only 1 copper coin, and 1 cent was equivalent to 4 copper coins.

After working for more than 10years, Tay saved up enough to start his own small firm, dealing with salted fish. He was just 26 years old. His reputation for being hard working and trustworthy led to the expansion of his business in Indonesia

In 1938, Tay noticed that local transportation was inadequate and started the Tay Koh Yat Bus Company. He built up his fleet to 120 buses and became the largest bus operator among the 10 other bus companies.

But more than buses, Tay was admired for his patriotism and daring do in leading a 20,000 strong self defence force which he formed just before the Japanese invasion. His rallying cry “20,000 people, one heart.” The force helped to maintain order and prevent panic and chaos as people started to flee the country with the invasion of the Japanese forces.

Tay stood his ground until the eleventh hour and escaped to Indonesia to escape certain death only on the eve of the fall of Singapore. He was on the Japanese most wanted list. But before he left he had organised a 2000 strong rescue team, for people who injured by the Japanese air raids.

After the war, Tay returned and immediately started to compile the fatalities from his volunteer force and lobbied the colonial government for the same compensation given to widows and children of servicemen who died during the war. Initially rejected, he appealed and the government finally gave in.

Tay next went on to form the Singapore Chinese Appeal Committee for the Japanese Massacre victims to seek justice and compensation. It was estimated that some 50,000 people had died under Japanese hands.

In March 10, 1947, the War tribunal committee found Lieutenant General Kawamura Saburo, Singapore garrison commander and Lieutenant Colonel Oishi Masayuki Kempeitai commander guilty of war crimes and sentenced them to hang.

They had been in charge of the Sook Qing operation in Singapore which massacred thousands of ethnic Chinese.

Tay was invited to witness the execution of the two war criminals. Tay was one of only six people to witness the execution, such was his standing in the community. And, on seeing the two generals, he burst out in anger and sorrow:

“You have committed big sins and really deserve to die, but even when your soul descends to hell to suffer further punishment, still it is not enough to atone for your sins.”

Tay Koh Yat never lost his fiery nature. During the riots of the early 50s of union unrest and political instability, Tay who was by then also managing a newspaper became an indirect target. One day he received a phone call that 4 young people were burning his buses near Rex Cinema. He got his driver to take him to the scene of the arson. When he saw 2 young men burning his bus, he caught hold of one of them and exclaimed “How dare you, burn my bus!” But at 70 he was no match against a young rioter and barely escaped.

Tay Koh Yat’s tomb is in the line of the proposed new highway that cuts through Bukit Brown and his grave is slated to be exhumed, finally uprooting a pioneer and a hero who had always stood his ground.

His tomb is marked as A1 at Blk 5 division 1

A postscript on Bukit Brown ‘s war years: Many of the those who died during the 3 1/2 years of the Japanese Occupation had to be buried hastily in mass plots without tombs at the Paupers Section. They remain largely unknown.

A Singaporean recalls praying at the site of a similar mass grave where one of his relatives was buried during the war. The circumstances then dictated that bodies were collected and buried in a communal trench. This is in Block 5.

***

Here’s another blog on another war hero buried at Bukit Brown: Wong Chin Yoke. (credit: the Rojak Librarian)

Here’s a newspaper article on Wong Chin Yoke.

***

Other family details:

Marriage certificate of Tay Koh Yat’s daughter with Tan Ean Kiam as marriage solemnizer and 5 colored flag, the national flag at that time (on display at the Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall)

Recent Comments