Seh Ong Hill

Introduction

The Bukit Brown Cemetery Complex mapped out by Mok Ly Yng based on the land lot tracings from this map shows a surviving area of approximately 390 acres. The biggest Chinese cemetery outside of China consists of four identifiable cemeteries bordering each other : Bukit Brown, Lau Sua (Old Hill), Kopi Sua (Coffee Hill) and Seh Ong Sua (Ong Clan Hill) This map shows the various cemeteries demarcated

In the following article Jave Wu traces the link between Seh Ong Sua (Ong Clan Hill) and the origins of the Hokkien Ong Clan way back to dynastic China, 550 BC. Jave researches & consults in Chinese culture, history & religion, specialising in Taoism.

Seh Ong Sua and the Hokkien Ong Clan (星洲姓王山與開閩王氏)

By Jave Wu

Seh Ong Sua is also sometimes known as “Tai Wan Sua” in Hokkien. “Tai Yuan Shan” (太原山 pinyin: Tàiyuán😉 refers to the capital and largest city of Shanxi Province in North China. )

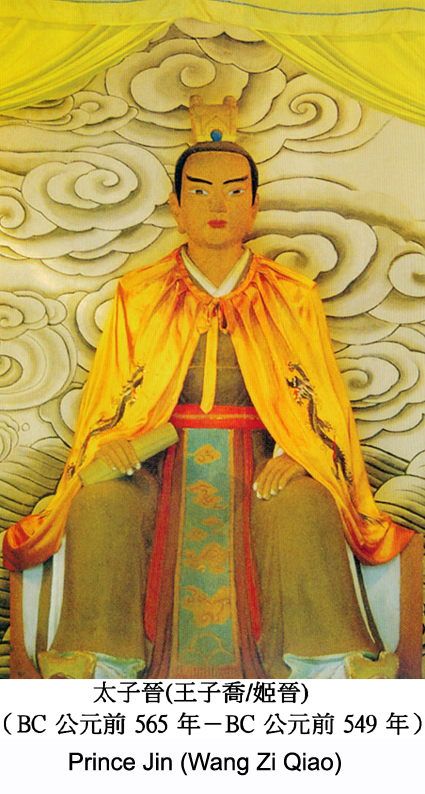

The connection began in the late Zhou Dynasty when the first ancestor of the Ong clan, Prince Jin (太子晉), also named Wang Zi Qiao (王子喬/姬晉), was stripped of his royal status by his father King Ling of the Zhou (周靈王) in 551 BC (周靈王廿二年).

Born in 565 BC, Prince Jin was supposed to be a descendant of the Yellow Emperor (黃帝). He was a precociously intelligent child who often offended his father because he was given to speaking out in the face of his father, King Lin’s stubbornness and lack of wisdom.

During a morning assembly of the Court, King Ling suggested an impractical method of dealing with the frequent flooding in the kingdom. Prince Jin was about 14 or 15 then and he objected to his father’s suggestion in front of the other court officials, which placed King Ling in an awkward situation. Outraged, the King stripped Prince Jin of his royal title. The Prince was disappointed and foresaw the collapse of the Empire. He suffered from depression for 3 years before passing away in 549 BC at the age of 17, leaving behind his wife and a young son, Ji Zong Jing (姬宗敬).

Soon after Prince Jin’s death, King Ling also departed the mortal world. Prince Jin’s younger brother, Prince Gui (太子貴), ascended the Zhou throne as King Jing (周景王). At a young age, Ji Zong Jing was appointed as the Premier (大司徒 – 相等丞相之職) by his uncle King Jing.

Well aware that his uncle was an inept ruler like his grandfather, and seeing that the Empire was collapsing, Zong Jing resigned from his post and left the Imperial court, escaping to Taiyuan City (太原市) in Shanxi Province (山西省) to take refuge. To avoid being recognised, he changed both his surname & name.

As he was a descendant of the Imperial family, he used the Chinese character “Wang” (王 = king or “ Ong” in Hokkien) in place of his actual surname “Ji” (姬), and changed his name from “Zong Ji” (宗敬) to “Rong” (榮). Henceforth, he was known as Wang Rong (王榮), symbolising the royal lineage will be “prosperous & continuous.”

The Wang clan took root in Taiyuan City and the descendants multiplied over the generations. By the Tang Dynasty, there were many people with the surname Wang (Ong) all over the Middle Kingdom (中原). As a result of this historic beginning, those of the surname Wang (Ong) refer to Taiyuan as their place of origin. This also explains how the name of Taiyuan Shan in Singapore came about.

From 615 to 755 AD, after the rebellion by An Lushan (安祿山), southern China (especially the Fujian area) was in turmoil with constant strife between warlords. In 885 AD, 3 brothers, Wang Chao (王朝), Wang Shenzhi (王審知) & Wang Shenggui (王審邽) recruited an army which drove into southern China and brought peace to the troubled region. To protect the common peoople from further suffering, the three brothers built a kingdom in Fujian which came to be known as the Min Kingdom (閩國). The establishment of the Ong clan in southern China could be traced to this victory.

During the late Ming & early Qing Dynasties, many Hokkien Ong clansmen left their homeland in Southern China for Southeast Asia. By the late Qing Dynasty, their descendants had settled in many parts of Southeast Asia including Singapore.

In 1872, the members of the Hokkien Ong clan in Singapore decided to have a place where the living could reside and where their departed ancestors could be buried. Three of them, Ong Ewe Hai (Wang You hai 王有海), Ong Kew Ho (Wang Qiu he 王求和) and Ong Chong Chew (Wang Zong zhou 王沧洲 ) contributed $500 each to buy a plot of land between Toa Payoh and Bukit Timah, approximately 97 acres which was to become Seh Ong Hill (姓王山)

Soon after the cemetery was established, the three good friends proposed building a temple there to honour the first ancestor of the Hokkien Ong clan, with the assistance of other clan members. This was the “Temple of the King of Min” or Min Wang Ci (閩王祠). After the temple was constructed, Wang Youhai (王友海) set off for Fuzhou in Fujian Province in China (中國福建省福州市), where he brought back the ancestral urn and paintings of the three Wang brothers who established the Min Kingdom from Zhong Yi Wang Temple in Qing Cheng Si Street (慶城寺街忠懿王廟).

In 1875, the Hokkien Ong Ancestral Temple (閩王祠) was set up to assist Hokkien Ong clan members. In 1944, the name of the association was changed to Hokkien Ong Temple General Association (閩王祠公會) and in 1970, this was changed again to Singapore Hokkien Ong Clansmen General Association (開閩王氏總會).

From 1982 to 1990, the land around Seh Ong Hill was developed and some vacant land was acquired by the government. Using the compensation which amounted to approximately 9 million dollars, the clan bought a piece of land in Bukit Batok Street 23 where the Hokkien Ong Clan Temple was rebuilt. The construction was completed in 1999 and then President Mr Ong Teng Cheong was invited to be the Officiating Officer for the grand opening of the new temple on 2 May 1999.

Till today, the Hokkien Ong clan still conducts annual ceremonies for the Spring and Autumn honouring their ancestors in Singapore and as well as in China. it allows the clan to remember the credit & merit they had accumulated in building the “Hokkien Ong Kingdom”

“The trees have roots, and the water, its source.”

Dedicated to the Ong clan & its ancestors

References:

http://bukitbrowntomb.blogspot.com/2011/11/blog-post.html

History of Clan Associations in Singapore Vol. 2, SFCCA 2005.

One Hundred Years’ History of Chinese in Singapore 新加坡华人百年史。

For more of the Ong connection at Bukit Brown – http://bukitbrown.org/a-great-hill-for-us-to-remember and A Grand Repose.

Pantuns

by Norman Cho

The pantun is sometimes described as Malay poetry. It consists of stanzas made up of rhyming quatrains (4-liners). Its history was thought to have originated from golden period of the Malays during the 15th century. When a pantun is sung, it becomes the dondang sayang (melody of love). Normally, the last word of the first line would rhyme with that of the third line, and, the second line would rhyme with the fourth line. If this is not achievable, then the rhyme would just be at the first and third line, or, the second and fourth line.

Composing a pantun is no mean feat. One must first have an excellent grasp of the Malay vocabulary in order to select meaningful words to rhyme while remaining contextually precise, which is equally challenging. The first two lines of the stanza will describe a situation/scene while the next two lines will either provide a follow-up on the situation/scene or the meaning behind the situation/scene. Very often, the pantun would carry hidden meanings and one would need to read between the lines. In the old days, nyonyas could pass sarcasm through the subtlety of a pantun to unsuspecting peers! It takes wit to compose a pantun and intelligence to decipher its intended meaning.

Here is an example:

Chek Syed turun ka paya

Bua kana tiga persegi

Jangan di rompak ruma saya

Tiang nya batu dinding nya besi

Mr Syed went to the marsh

Triangular are the olives

Do not rob my house

Its pillars are stone and its roof metallic

(Intended meaning: I am but a poor person)

– Source: malaycivilization.ukm.my

Dondang Sayang is pantun in its sung form. This art-form was believed to have been originated from Malacca during the 16th century from the music that was brought in by the Portuguese when they colonised the settlement. Western musical instruments like the violin and the accordion would accompany the Malay drums and the gong. A topic would first be selected and an impromptu quatrain would be composed and sung using this quatrain as a challenge to another singer who must sing a reply in the context of the topic. It is indeed a challenge of wits and words!

The Babas and the Nyonyas are adept in the art of pantun which they had adopted from the Malays. One of the exponent of this art-form is Baba Koh Hoon Teck. Not only did he actively participated in the Dondang Sayang but even composed and published books on Pantuns which were published by his company, Koh and Company.

Koh HoonTeck (photo: Cheah, J. S. (2006). Singapore: 500 early postcards (p.11). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.)

Koh Hoon Teck was laid to rest at Bukit Brown Cemetery and sent off with pantuns which was his dying wish. He died on Valentine’s Day 14th February 1956 according to an article.

Here’s a tribute to Koh at his tomb during the Peranakan Trail at Bukit Brown Cemetery in 2011

Mr. G.T Lye gives a spontaneous rendition of a pantun and shares some anecdotes at the tour, captured on video by Victor Yue

You can listen to a performance of dondong sayang by the late Baba William Tan

By Catherine Lim and Ang Yik Han

Date line Sunday 22 April 201

A week after the traditional fortnight period of observances for family Qing Ming, a group of tomb keepers observed a collective Qing Ming for the tombs under their care. The group of 5 take care of some 200 graves in blocks 5 and 2 at Bukit Brown. A core group of 3 has been observing this practice for some 20 years. They were joined this year by a mother and daughter team. The tomb keepers Qing Ming practices follow closely those observed by families with one exception. It has has three objectives: first, to honour the dead; second, to thank the “Gods” for their livelihood and pray for their continued support; third – the exception – to ask for forgiveness for any unintentional offence caused in going about their duties in the past year and pray for continued protection,

The tomb keepers of blocks 5 and 2 have commandeered a staked tomb which will have to make way for the highway. The family don’t mind. It is a cool corner to rest up, a strategic meeting point for their clients who are descendents of those buried and this was where operation Tomb Keepers Qing Ming gathered.

As they went about their preparations, there was no set order of who does what or who should pray first. But there was a great sense of duty and mission from people who knew just what to do intuitively, honed by years of practice and mutual respect.

Ah Chua at 80 years old, is the eldest tomb keeper and stops to pose for the camera. The younger tomb keeper (in blue) is responsible for getting supplies and general organisation. The lady tomb keeper in pink is part of a daughter and mother team who for this Qing Ming joined this group. They help in cleaning and sweeping because of the additional work load at the blocks which are heavily staked. Mother and daughter have their own “turf” at another block which was first looked after by husband and father who has passed away.

The tomb keepers pray to 3 deities for Qing Ming:

1)The Earth Deity Tu Di Gong (土地公) 2) Another earth deity Tua Pek Kong (大伯公) for wealth and fortune 3) Mountain Deity( (山神) so tomb keepers won’t get lost in the hills and undergrowth . 山神 is important especially to the tombkeepers

Each tomb keeper lights up 11 joss sticks – 5 to represent the 5 directions which the earth deity encompasses, 3 for the wealth deity and 3 for the mountain deity

The second make shift altar is set up across from the earth deity's for the ancestors whose graves are tended by the tomb keepers (photo Catherine Lim )

The two elders beseech the ancestors to partake of their offerings and to look after them as well (photo Catherine Lim)

Preparations for the burning of the paper offerings

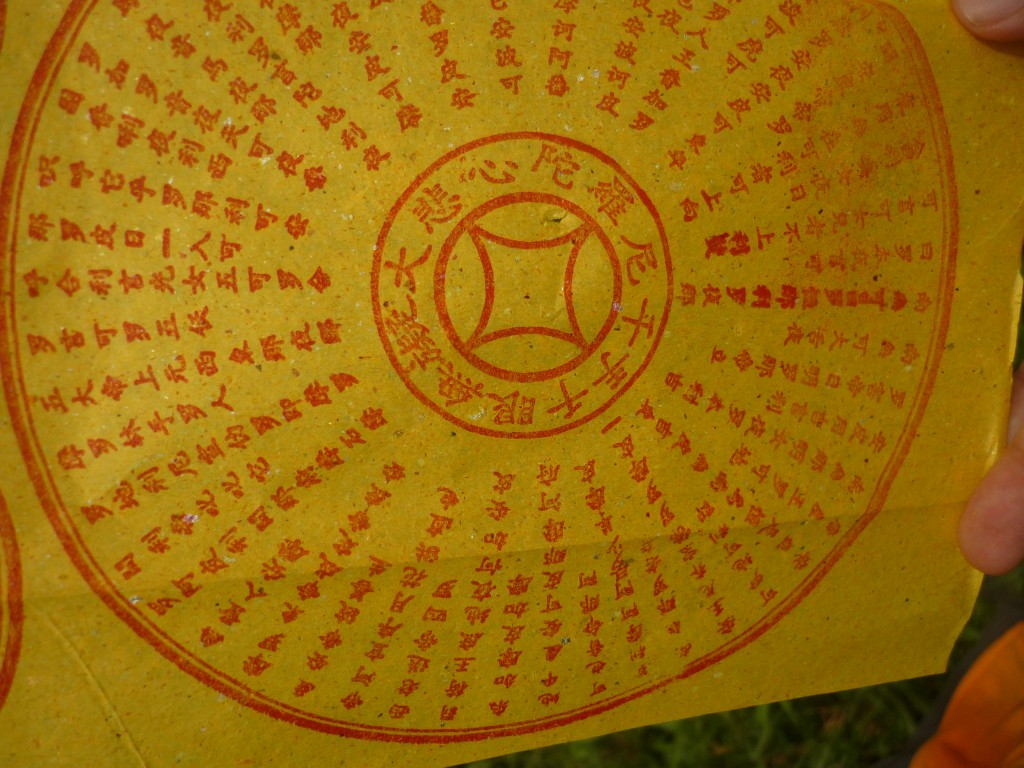

Stars of fortune, prosperity and longevity imprint. This type of paper is also known "Heavenly Emperor " - 天公金 paper and is the only destined for heaven (photo Catherine Lim)

Gold for the underworld, folded just so to facilitate the burning and quick passage down to hell. (photo Catherine Lim)

You can never have too much currency in the underworld, silver and gold paper and ingots (photo Catherine Lim)

"Rebirth mantra paper" - 往生纸 - also known as "seven mantra paper" (七言咒纸), offered to the spirits to help their rebirth, each circle represents a mantra (photo Catherine Lim)

At the earth deity’s alter, the stack is also being built.

She soldiers solo on building her stack of paper offerings at the earth deity's altar (Photo Catherine Lim)

Bangsawan and the Bukit Brown connection. One of the earliest impresarios of traditional Malay Opera is buried in Bukit Brown and is highlighted in Group 2 Tour.

The Beginning of Bangsawan in Singapore

by Norman Cho

Before the advent of the television or the sound movies, theatrical performances were the few forms of entertainment available to the masses. One of which was the Bangsawan. The Bangsawan (Malay Opera) troupes consisted of professional Malay actors. The origins of the Bangsawan probably originated from the western plays. A small orchestra consisting of the violin, the accordion and local Malay percussion instruments such as the kompang, would normally accompany the stage-acts. Comedy and tragedy were the common genres. Stories which imbed morals were often told through these plays. While the plays were in Malay, the stories were adapted from legends and folklore from diverse origins such as Chinese, European, Hindi, Arabian and Malay. The classical Malay language was normally used. This would be a higher form of Malay that was used by the Malay Royal Courts, which was archaic.

The most renowned was the Star Opera Company (1909 – 1927) which was owned by the Peranakan brothers – K.H. Cheong (Cheong Koon Hong) and K.S. Cheong (Cheong Koon Seng) and was managed by their nephew Y.L. Tan (Tan Yew Lee). It was situated at Star Opera Hall – Theatre Royal, North Bridge Road. They accepted reservations through phone bookings as early as 1918. Tickets costs between $0.50 to $5. Star Opera was so popular that it received patronage from various Malay Royals like the Sulatan of Trengganu in 1910. Even the Europeans attended its 1914 production of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” in Malay.

Their star artiste was Khairudin, also popularly known as Tairu (Tairo). His name was synonymous with the Bangsawan. He was so sought-after that his performances were frequently sold-out. As with many movie stars of today, fame invited gossip. Magic charms had been suggested for his unwavering popularity. The nyonyas mesmerized by Tairu’s dashing good looks, literally threw their jewellery on stage after each performance – a diamond ring or a hurriedly unfasten kerosang intan (diamond brooch) being the commonest items. Flustered Babas forbade their wives from attending his performance. His career peaked during 1918 but he stopped performing for the Star Opera around 1924 to start and star in a very successful company called “Dean’s Opera” also at Theatre Royal, North Bridge Road. He had probably taken over the venue from Star Opera Company. By then he billed himself as Kairo Dean. Born in Hong Kong in 1890, he came to Singapore in 1900 and studied in Belilios Public School. He was not very good at his studies and worked as a handbill boy for Wang Kassim at the age of 14, earning 15 cents per day. He was talent spotted by its director Gulam Mydin and the rest is now history…

Over at Frankel Estate’s Opera Estate, streets were not only named after European Operas like Tosca, Aida or Figaro. Jalan Bangsawan, Jalan Khairuddin and Jalan Bintang Tiga of the Malay Opera world could also be found.

More on Bangsawan by Norman Cho here

Recently Bangsawan was revived by the Singapore River. Read Jerome Lim’s blog for more.

This article is adapted by Norman from

“an article first published in The Peranakan, Issue 3, 2011, pp. 3. Reproduced courtesy of The Peranakan Association, Singapore”

淸明- 杜牧 (唐著名詩人)

淸明時節雨紛紛 qīng míng shí jié yǔ fēn fēn

路上行人欲斷魂 lù shàng xíng rén yù duàn hún

借問酒家何處在 jiè wèn jiǔ jiā hé chù yǒu

牧童遙指杏花村 mù tóng yáo zhǐ xìng huā cūn

Incessantly the rain falls during Qingming

On the roads are travelers deep in sorrow

Where is there a tavern to be found?

The shepherd boy points to Xinghua (Almond Flower) Village in the distance

(poem by Dumu translated by Ang Yik Han)

My Cheng Beng 2012 is a photo essay by Toh Zheng Han in memory of his late Ah Chors (great grandparents), Ah Kong (grandfather) and Ah Ma (grandmother) It marks his family observance of the festival and perhaps a coming of age for him in a year which has seen him playing his part to save Bukit Brown. Zheng Han is a 3rd year student, currently studying English and History at NTU/NIE.

Reflection

On the morning of 31st March 2012, three days before the actual day of Cheng Beng on 4th April my family and I headed to Track 14 (Old Choa Chu Kang Road) to the Hokkien Cemetery and Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery to pay respect to our ancestors. It had rained nonstop the night before. The poem 淸明- 杜牧 (唐著名詩人), captured the mood of the day, perfectly.

I only remember tagging along with the family for Cheng Beng about five years ago. I did not know why I wanted to go then. Maybe I thought it would be somewhat of an adventure to be climbing up the hills to visit my ancestors.

Recently, many Singaporeans including me have been trying to save Bukit Brown Cemetery from an 8 lane highway because we feel it is an intrinsic part of our nation’s history, heritage and habitat. Although I do not have any ancestors buried at Bukit Brown, it spurred me to find out more about my country and my ancestors. Personally, I feel that it is only by being able to find out about my country’s and ancestor’s histories that I am able to understand more about Singapore and myself. Cheng Beng offered me a chance to reflect upon this, to help me connect the past to the present and future; it reminds me that Singapore is home from the very day my great grandfather decided to make this place his home.

Family History (paternal)

This year, I decided to write this short reflection and take my camera to snap shot my family’s past. I have always wondered how my ancestors made the long and difficult journey out of their village many kilometers inland of Quanzhou, Fujian to Singapore without modern transportation such as cars, trains or planes. Instead they traveled the arduous journey by a boat all the way to Singapore. I guess I will never be able to find out or fully understand how it feels to leave home and make a new life for myself in a strange land. But I feel fortunate because my ancestor took that journey and I came to be born here.

My paternal great grandfather passed away about 20 years after arriving in Singapore a few years before the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. My father never knew him. Of my paternal great grandmother (his grandmother), he has only very vague memories as she passed away in the mid 50s a few years after he was born.

My father recalls life was tough growing up. He was one of 10 children and his parents – my grandparents – eked out a living raising poultry and pigs, and growing vegetables. Meals consisted mostly of porridge with soy sauce and some vegetables, and only occasionally a treat of meat. I have wondered how it would have felt to eat this meager meal day in and day out. But I am also guilty of complaining at times when my father cooks and I ask ‘Why is it the same thing again?”

It has only been in recent years that I felt a compulsion, a hunger to find out more about my family’s past and by extension to get a sense of my country’s past. Of course I realised I am no longer able to ask or hear stories from my grandparents who both passed away more than 10 years ago. I had not realised how much my grandparents doted on me when I was a child. But I am not about to let this deter me as I turn to my Ah pek (阿伯/ uncle), Ah kor (阿姑/ auntie) and the extended family to find out about my history, my story.

Cheng Beng 2012

1st Stop – Paternal great grandfather up the hill @ Track 14 Hokkien Cemetery

On top of a hill the simple pre- war grave of my paternal great grandfather, made almost entirely of bricks

The five-coloured paper represents the 5 cardinal directions and signifies that the grave has been visited. Some people choose to put the paper in the form of a flower for both aesthetic and pragmatic purposes, as paper can't be blown away by the wind

Some vegetables growing out of a grave about 3 metres away from my great grandfather’s grave

First up, offerings for the Earth Diety consisting of tea, sweets and biscuits together with the incense, special candles and joss paper that my uncle is burning. 3 incense sticks at anyone time

2nd Stop – Paternal great grandmother mid-hill @ Track 14 Hokkien Cemetery

Shock when we reached great grandmother’s place. The heavy downpour throughout the night caused some flooding, or ‘im chwee’ in Hokkien. The flood was cleared by two of my Ah Peks later.

"Huat Kueh"on the headstone of my great grandmother together with red coloured paper taken from the stack of 5 coloured paper. Some use any stone or bricks in place of the Huat Kueh

Great grandmother till clear more than half a century later. No renovating done. You can also see the company that built her grave

2 sons and 7 grandsons listed. In the old days, many graves did not have names of daughters and granddaughters listed.

Final picture with my great grandmother before we left for Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery. Notice the moat that prevents water from accumulating and which directs and channels water downhill. There was some flooding earlier, because of soil and debris that had choked the exit of the grave.

3rd Stop – Paternal grandfather @ Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery

My grandfather’s grave. I noted the difference between the size of a new grave and the old graves earlier.

Incense paper, gold, silver etc for my grandfather. Notice the circle and dot in the middle? It ensures that this gets sent to only my Ah Kong. Just like how a crossed cheque works

4th Stop – Paternal grandmother @ Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery

Quiet moment for my dad with his late mother. Last stop of the day before we went with my Ah Peks (uncle) and Ah Kor (aunties) to have dinner

Favourite drink (Milo) of my grandmother or Ah Mah as I address her in Hokkien. She also likes to eat kuehs like Kueh Bulu and cakes like Pandan Cake. It was only recently that I heard stories from my mother that my late Ah Mah (as a 70 year old lady) used to take a bus alone all the way from Changi to my maternal grandmother’s house at Joo Chiat to visit me when I was a child. Gamsia Ah Mah. Gamsia (Thank you)Mama

Lost in a sea of graves - a failed attempt to locate my maternal great grandfather who passed away in the late 1970s.

Postscript:

I wish to emphasize that every one of us needs to treasure the time we have with our loved ones and not wait until Cheng Beng to do so. While Cheng Beng gives us a formal occasion for the extended family to gather and reminisce about the past, what is even more important is the need to also enjoy the present and love your parents. Treasure the past, and enjoy the present – so that we can eventually embrace the future.

Peranakans in Mourning by Norman Cho

The three most important events in one’s life is thought to be Birth, Marriage and Death. They are seminal. Therefore, the Chinese conceived special rites and rituals associated with each of these occasions.

Traditionally, when death occurred in a Peranakan home, white masking tapes would mark an “X” over the jee-hoe(family plaque) that was hung above the main door as a sign that the residence was in mourning. The main door and the front windows were similarly demarcated. All mirrors in the house were either covered with white cloths or be “X” over with white masking tapes. This was done to prevent deflecting the soul of the recently deceased. If two deaths occurred in a family consecutively, mourning favoured the latest death.

If the deceased had his funeral done away from his own home then a chye kee (red banner/bunting) must be hung at the main door of the residence that hosted the wake. This was to show that nobody from that house had died.

The full duration of the mourning period was three years. This is known as tua-har berat (heavy mourning). It is divided into stages. For the first 100 days, the mourners would wear traditional Chinese mourning garb that was made from belachu (sackcloth material). The womenfolk who would normally don the chignon had to let down their hair as an expression of grieve. The subsequent one year, the mourners would wear fully black baju and sarong (nyonya attire). The nyonya would start doing her chignon during the “black” mourning stage. The following stages would be one year of chit-itam (black-white combination), then six months biru (blue) and the final six months of ijoh (green). Interestingly, each stage is not customarily carried through to the full term for each stage. The mourners would perhaps mourn only 90 days out of the 100 days or 11 months out of the one year.

During the various stages of mourning, the nyonyas would adorn themselves with pearl mourning jewellery set in silver. The whiteness of pearl and silver was thought to be apt for mourning. In the Victorian west, pearl mourning jewellery was also very popular and the pearls signified droplets of tears. It was little wonder that the nyonyas who were under British adopted the same practice. Such pearl jewellery was not only worn by the mourners but also interned with the deceased. It was known that some living nyonyas would commission replicas of their favourite gold diamond jewellery in silver and pearl, to be worn when they depart.

The working male normally wore traditional sackcloth mourning attire till the body was interned. Then, they would switch to wearing a small square patch (made from sackcloth) on the shirt sleeve for 100 days. If the deceased was male, the patch would be worn on the left arm. However, if the deceased was female, the patch would be worn on the right. Subsequently, they would wear a black arm-band for one year, in accordance with the western practice.

When the nyonyas buang/bukak/lepas tua-har (terminates her mourning), she would signify this by wearing bright coloured attire such as red and insert bunga siantan (ixora) onto her chignon. The end of mourning is marked by a definitive splash of colour.

Bunga rampai - shredded pandan with sandalwood dust; yellow and white "chempaka" flowers; jasmine (bunga melor);rose petals;incense tablets (kemenyan) and candles.

A typical Peranakan offering

a.t.bukitbrown is looking for contributions to Culture which touches on the contemporaneous history and customs of the lives of those buried in Bukit Brown, which date from 1833, and which Bukit Brown Cemetery’s operational years cover (1923-1973).

Topics to cover a range of from the significance of offerings to ancestors during Chinese New Year and Qing Ming, to burial and funeral customs and traditions such as marking the period of mourning with observances in dress and diet.

We need contributions which will help the community understand the meanings behind the rituals and traditions We also welcome personal memories of familial practices encountered in the early years of Bukit Brown

Please send contributions to a.t.bukitbrown@gmail with topic : Culture

Recent Comments