2015

Aug

14

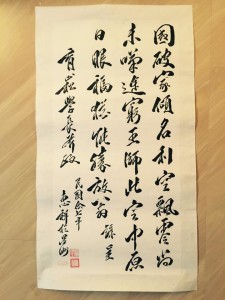

Lim Hui Siang and his Calligraphy

1It all began when a descendant asked for help in the FB group Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown in locating the grave of his maternal grandmother Yang Shu Hua 楊淑華, whom he just discovered was buried in Bukit Brown.

Madam Yang it transpired is the first wife of Prof Lim Hui Siang (pinyin Lin Huixiang, 林惠祥) who was a co founder together with Tan Yeok Seong of the Amoy Anthropological Museum in 1935. The museum still exists today.

Tan’s son Alex then contributed a photo of both, followed by a calligraphy by Prof Lim dedicated to his father.

Jason Kuo a member of the group, impressed by the calligraphy started to unravel its meaning. Together with inputs from Khoo Ee Hoon, this is the translation arrived at with disclaimers.

By Jason Kuo:

As far as we can decipher, these are the character in the piece (all transcriptions in traditional characters):

國破家傾名利空

飄零尚未嘆途窮

王師北定中原日

眼福猶能勝放翁

Translated:

When the country is broken and families are upturned, fame and fortune mean nothing.

Although I am forced to wander, I am not yet lamenting that our cause is hopeless.

My eyes may be luckier than that of Lu You, for I may (live to) see the day when the righteous army sweeps north and pacifies the central plains

[i.e., when we have driven out the Japanese].

A line by line breakdown:

國破 guo2 po4, the broken country

家傾 jia1 qing1, the family fallen (families upturned)

名利 ming2 li4, fame and fortune

空 kong1, emptiness, nothingness (also with Buddhist connotations)

Probable translation:

When the country is broken, and families upturned, fame and fortune become meaningless

飄零 piao1 ling2, wandering (often used as in “forced to flee”)

尚未 shang4 wei4, yet, not yet

嘆 tan4, lament, sigh, cry

途窮 tu2 qiong2, no more paths, dead end, no way to go.

Probable translation:

(Although) wandering (as a refugee), (I am) not yet lamenting that (we have; China has) reached a dead end (i.e., that our cause is hopeless)

王師 wang2 shi1, literally, the king’s army, imperial army, also implies righteous army, since 王道 is the righteous (Kingly/ Princely) Way. Here a reference to the Chinese army.

北定 bei3 ding4, literally, “north pacify”. Pacifying the north (much of which was then occupied by Japan).

中原 zhong1 yuan2, the Central Plains, the heartland of traditional China and the cradle of Chinese civilization.

日 ri4, day

Probable translation:

The day when the righteous army sweeps north and pacifies the Central Plains.

*(Note that this is a verbatim copy of a line from the famous Southern Song Dynasty patriot, Lu You 陸游, whose style name is Fang Weng 放翁 (man who has discarded everything?),

眼福 yan3 fu2, gift for the eyes, i.e., lucky enough to get to see ….

猶能 you2 neng2, can even

勝 sheng4, victorious, be better than

放翁 Fang4 Weng1, the patriot Lu You, or Lu Fangweng

Probable translation:

My eyes may be lucky enough than those of Lu Fangweng (to see the day when the Chinese army triumphs).

The poem was written in 1938, one of the darkest periods in modern Chinese history. However, though defeated in many battles, and with its capital Nanjing routed, the Chinese army continued to defy the Japanese, and achieved a few brilliant victories such as Taierzhuang. Lim’s poem alluded to two Southern Song patriots. The first one, Lu You, was born in the Northern Song era but died during the Southern Song, and saw northern China being conquered by the Jurchen (女真) Jin 金 dynasty. Throughout his life Lu advocated the re-conquest of the north, but the Southern Song court, having fled the north (and with two of its emperors held hostage under the Jurchens), was in no mood for such an undertaking. (Some also speculate that the Southern Song emperor may not have wanted his captured father and brother to return to the throne.) Compare one of Lu’s most famous poems against our 1938 poem:

死後元知萬事空

但悲不見九州同

王師北定中原日

家祭毋忘告乃翁

Rough translation: Although I know that when I die, all will be empty (notice use of word 空, as in 1938 poem), but I am saddened that I cannot see the reunification of China. When the righteous army sweeps north and pacifies the Central Plains (note direct copy by 1938 poem), do not forget to tell this old man (of the good news) during your ancestral rites.

The second patriot is the famous Wen Tianxiang 文天祥. He lived much later than Lu and saw the conquest of the Southern Song by the Mongol Yuan dynasty. He died while in prison in the Yuan capital, modern Beijing. (In fact, it was the Mongols who made Beijing the capital for the first time of all of China. Before then Beijing had often been a capital for divided regimes.) Wen’s most famous work is the Song of Righteousness 正氣歌. In any case, (thanks to research by Khoo Ee Hoon,) he also wrote these words in his poem, En Route to Yangzhouli 至揚州里: 飄零無緒嘆途窮, roughly, Endlessly wandering, I lament that our cause is lost. Compare this against the 1938 poem, where the author is much more optimistic about China’s prospects (but using the exact same words except replacing “endlessly” with “not yet”).

It is somewhat interesting that Mr Lim chose two tragic figures as his role models. One saw the destruction of northern China, while the other saw the conquest of the remaining part of China still under Han rule.

Bonus points: Mongol rule in China has been deeply influential. It was the first time that the historically Han areas of China and the Tibetan areas came under one ruler. Since the modern Chinese states (both the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China) both view the Mongol Yuan dynasty as a continuous Chinese (though not Han) dynasty, Chinese sovereignty over Tibet is traced to the Mongol period. Some Tibetans have a different view: they argue that China was conquered by the Mongols, and that the Mongols ruled both China (i.e., what Chinese nationalists would call the Han areas of China) and Tibet as parts of their empire. Under this view, after the Mongol defeat, China (under the Ming) and Tibet became separate countries again. This argument is compounded when the Manchu dynasty (a successor to the Jurchen Jin dynasty, ironically) conquered Ming China, the Mongols, and Tibet. When the Republic of China defeated the Qing in 1912, the new state’s view was that it had succeeded to all of Qing territory, which it viewed as indelibly “Chinese”. Many Tibetans, however, believed that the Qing were also an alien empire, and that its defeat meant that “China”, Tibet and Mongolia would go their separate ways. In modern times, this view has become academic as the People’s Republic has firmly secured its hold on Tibet (while northern Mongolia, under Soviet support, has long been independent. It’s ironic that most ethnic Mongolians still live within China’s borders, in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region). It is still an emotional issue, though. The Dalai Lama now accepts Tibet as part of the People’s Republic, and only argues about the degree of autonomy Tibet ought to have. However, he is very reluctant to state that Tibet has been part of China “since ancient times”. Yet this statement has been insisted upon by the PRC government.

Further comment: Because the Republic of China, in the form of the Kuomintang regime, was later defeated in the Chinese civil war, the contributions of China during World War II has been muffled for much of the last 70 years. But with greater openness in mainland China and more Western scholarship of that era (see Rana Mitter’s excellent work), the Chinese war effort under Chiang Kai-shek’s government has generated renewed interest, and usually a more favorable assessment. Throughout Chinese history, it has been extremely rare for southern regimes to reconquer the north. If anything, the thrust of history has been for the north (often non-Han regimes) to conquer the south (almost always a Han regime), and with reunification leading to hanification of the non-Han, and ironically expanding China’s territory (so one could say China expands its territory through defeats). The ROC was the only Chinese regime in centuries to accomplish total victory over an alien aggressor. On top of that, it had regained control of both Manchuria and Taiwan, which were thought to be long lost to the Japanese.

=================================================

So what became of the search for Madam Yang’s grave at Bukit Brown? It was found to be one of the tombs affected and already exhumed for the highway. Her grandson is arranging to claim her remains to be interred by family.

All remains not claimed are kept for a duration of 3 years for any claimants before it is cast to sea

Another amazing unfolding of knowledge and events! The power of crowd-sourcing, the willingness to share is amazing! Bravo to everyone!