Old House at Ang Siang Hill

by Arthur Yap

an unusual house this is

dreams are here before you sleep

tread softly

into the three-storeyed gloom

sit gently

on the straits born furniture

imported from china

speak quietly

to the contemporary occupants

they are not afraid of you

waiting for you to go

before they dislocate your intentions

so what if this is

your grandfather’s house

his ghost doesn’t live here anymore

your family past is

superannuated grim

which increases with time

otherwise nothing adds or subtract

the bricks and tiles

untill re-development

which will greatly change

this house-that-was

dozens of it along the street

the next and the next as well

nothing much will be missed

eyes not tradition tell you this

an extract from Thow Xin Wei who writes of the poet Arthur Yap’s work….

In “old house at ann siang hill”, a similar voice seems to suggest that even tradition is expendable in the pursuit of progress:

so what if this is

your grandfather’s house

his ghost doesn’t live here anymore

your family past is

superannuated grim

which increases with time

otherwise nothing adds or subtract

the bricks and tiles

untill re-development

which will greatly change

this house-that-was

dozens of it along the street

the next and the next as well

nothing much will be missed

eyes not tradition tell you this

In contrast to the opening of the poem, the viewpoint has shifted to that of the civil servant, with the casual disdain for the past, the calculative dismissal, and the firm conviction that “re-development” and change will mean progress; to hold on to the past is merely nostalgic sentiment, an old fashioned belief in “ghosts” that is not congruent with the rapidly modernising social and physical landscape of Singapore.

Interactions between those in authority and those subject to it also feature in Yap’s poetry. In “an afternoon nap”, an “ambitious mother… proclaiming her goodness”, punishes her son for his mediocre grades, while the “embittered boy” proclaims his “bewilderment” and berates her for her “expensive taste for education”. Both proclaim the other’s “wrongs”. It is tempting to read this poem as a metaphor for the relationship between government and citizens in Singapore, especially given the paternalistic character of a government which institutes policies regarding its citizens’ child bearing, hygiene and courtesy habits.

The Origins, Traditions and Beliefs of what today has become popularly known as “The Hungry Ghost Festival”

by Victor Yue

Between the ancient Chinese characters and the modern English vocabulary, there seems to be a big mis-match as to what the festival is about. But for ease of communication, some terms that seem to be closest in translation would it seems, have to do. In some cases, such as events, more exciting phrases were coined in Chinese and explains I believe how we have arrived at the name The Hungry Ghost Festival.

The Origins

It is said that although the 7th Month event is an age old tradition and custom from ancient times marked during the 7th lunar month, the term “Gui Jie” meaning Ghost Festival did not appear until the Ming Dynasty. I am curious as to when the word “Hungry” was added into the Ghost Festival, making it the Hungry Ghost Festival. Indeed this additional adjective does much to fire up the imagination of the more impressionable young and those unfamiliar with the 7th Month event.

Older Chinese, simply call it Chit Gue (7th month in Hokkien), Por Tor (Pudu in Mandarin) or Tiong Guan Huay (Zhong Yuan Jie) which is probably more official as these are the words used in the posters and banners put up during this time.

As with most age old traditions, it’s difficult to separate the practice, beliefs and the myths. We tend to embrace them together and it becomes a colourful, cultural potpourri

How is it “celebrated”?

The 7th Month in Singapore means different things to different people. To believers and those who have “the third eye”, it is a month when the entities of the nether world come a calling. “Don’t go out late, Don’t go swimming” would be the warning from Grandma. The grandchildren would dutifully say “yes” and do exactly the opposite! And should anything untoward happen, Grandma would say “I told you so!” and follow up with making reparations to ask the “invisible” for forgiveness.

For the Hokkiens and Teochews (and probably for other dialect groups as well), on the first night of the 7th month, they would be lining up candles and joss-sticks to “welcome” the visitors (who might include their ancestors) offering them food and burning joss-papers (money). They do the same on the last day of the 7th month to send them off. In between, on the 15th day, they would also d0 another similar round of offerings. For the Cantonese, I understand that they do it on the 14th night of the 7th month.

A few days before the arrival of the 7th month, the organisers of the neighbourhood’s 7th Month prayers – officially called “Celebrating Zhong Yuan Jie” – will set up make-shift altar tables at a suitable place, usually close to a lift landing or a corner of an HDB block Some HDB block or blocks may have more than one group of Zhong Yuan Jie organisers. Most of these organisers would have continued since the days when the residents were from a different neighbourhood. They tended to follow the migration of many of the residents from the old houses (kampong /pre-war homes) to their new homes in housing estates.

Back in the good ole days….

In the old days (circa 1950s), this event lasting between one and three days in any neighbourhood was one that the kids look forward to. Most families would subscribe to one of the Zhong Yuan Jie (or Por Tor in Hokkien) having paid a dollar a month. During the Por Tor, the organisers would have the goodies as offerings to the Por Tor Gong (the Tai Shi Ya or Da Shi Ya) before giving each subscribing household a pail of these goodies.

Apart from the 7 essentials (柴米油鹽醬醋茶- charcoal, rice, oil, salt, soya sauce, vinegar and tea – what’s needed in a typical kitchen of the old days ) there might be half a braised duck or chicken, something that was a luxury in the 50s for most families. There would also be an abundance of fruits – from Rambutans to Buah Langsat to Buah Duku.

For children, it was like carnival time. Street wayangs – about the only open air entertainment and free to boot of those times, would spring up. They were set up so skilfully within half a day using only mangrove poles tied together by soaked split rattan, and wooden planks for the flooring. I remember taking a stool from my house to “chope” (reserve) a place to watch. The afternoon show was from 2pm to 5 pm and evening from 8pm to midnight. Food was close at hand. Hawkers would encircle the wayang stage and even underneath the raised stage, selling food such as oh-jian (the traditional barnacles in fried sweet potato flour with eggs ), traditional desserts (offerings from red bean soups to sweet potatoes to tau suan and bubur telegu), fried kway teow, shellfish (cockles and siput) and much, much more. And when I was bored with the wayang I would take a turn at the games station and try my luck at tikam-tikam – just folded paper that for 5 centsa pick, you get a a shot at winning a prize of some cheap toy or sweets. I hardly ever won anything.

In the streets of Chinatown

In the Chinatown of old, each house would, in step with the organising communities for Por Tor, set up their altar tables outside their house to make offerings. As the majority of such houses had multiple tenants, the landlord would lead in organising the prayers. The narrow streets meant street wayangs were allocated specific dates for the Por Tor. One would be able to see the offerings from the beginning to the end of the street, with the triangular flags stuck into the food/fruits fluttering in the wind.

Sometimes, the community prayer ends up with a grand dinner where items are auctioned off and money raised – the collection of which could take up to a year – for the next Por Tor. The funds help to pay for not only the event but also the food baskets.

Enter the getai …

Getais came on the scene in theearly 60’s and overtook the wayangs in popularity (photo by Victor Yue)

Getai probably started in the 60s and quickly held the crowd captive. But long before their entry, some street wayangs had some of their actors/actresses singing before the opera started, as a warm up act, but it did not develop further. It took off probably following the hey day of the wildly popular Wang Sar and Yueh Fong. The duo took Singapore by storm and everyone knew the exclamation “Wah Lao”. During that time, there were also the Getai entertainment establishments where one could pay for entrance and get a drink to watch. The last one, similar to those in Taiwan, to my memory must the one at the former Wisma Atria, which I would go with my classmates each Chinese New Year eve.

In Chinese temples

In the Chinese Temples, the offering on the 15th of the 7th month was to Di Guan, one of the three Officials of the three realms – Tian (Heavens): celebrated on 15th of 1st Lunar Month), Di (Earth): celebrated on 15th of 7th Lunar Month and Shui (Water): celebrated on 15th of the 10th Lunar Month.

According to Taoist beliefs, praying to Di Guan is to ask for elimination of sins and debts. It is from this occasion of praying to the Di Guan or Di Yuan that the world of Zhong Yuan Jie came about.

Family….

For the family, 7th month is also a time for them to remember their ancestors. During the old days, each family, would have their ancestral altar at home. For the Hokkiens it would usually be placed next to another altar dedicated to Tua Pek Kong. For their most recently departed – a parent or grandparent – the family, usually the grandma or mother would prepare the offerings. The departed and the ancestors further down the line would be’invited” to come and partake of the offering. For us kids, it was also another occasion we waited for, for it meant that we could have more elaborate dishes that we would not get otherwise. Chinese New Year and 7th Month are the two major occasions that children look forward to and our poor parents would dread it as they would need to find money to cook up at least something worthy for their ancestors.

Today, many would have have moved the family ancestral tablets to the temples and so, offerings would be at the temples. Food offering’s also became simplified with fast food that could be the packed from chicken rice to Kentucky Fried Chicken.

7th Month represents a spectrum of Chinese culture, of beliefs, tradition and customs, with variations for different dialect groups, and in some instances also influenced by the practices from ancestral place of origin in China. We remember our ancestors; we think about the wandering souls (those whom the descendants have forgotten or who may no longer have living descendants); we seek pardons from the Official of the Earth Realm. This we do, to preserve our unique culture which also evolves with the times.

Victor Yue is Taoist and spends much of his time researching and documenting Chinese religious practices and rituals.

Here is a video he took on a auction on Pulau Ubin for the Hungry Ghost Festival

Here is another of Victor’s video on “Breaking Hell’s Gates” – a rare ritual conducted only once every 5 years at Peck San Theng Temple in Bishan

At Bukit Brown during the 7th month, tour groups also encounter evidence of rituals and offerings

“Bukit Brown : What We Have Really Lost” by Joshua Chiang

(This essay first appeared on The Online Citizen on March 20, 2012 and is reproduced here with the permission of the writer)

On a separate note, I found out from one of the SOS Bukit Brown volunteers that Tan Tock Seng’s grave on a knoll at Havelock Road would also have made way for a road because – get this – the people who planned the road had no idea that the grave belonged to him. It was only through the intervention of activists that the tomb was saved. This is what happens when we’ve lost our roots. We even believe our ancestors are as equally pragmatic as us.

All Things Bukit Brown notes: Till today, there has been no engagement from the relevant bodies on Bukit Brown and development plans are proceeding, deaf to the community of diverse voices which has grown. More have been coming for public tours conducted by volunteers; it has become the subject of lessons, videos, books, heritage forums on and offline and incorporated into a play. Soon it will be the inspiration of the art of a New York artist. He is calling his next exhibition “Extinction”

by Catherine Lim

The tour on Sunday 22 July, starts off rather ignominiously atop a pedestrian bridge which spans a busy dual carriageway and ends with a touch of the macabre, sitting on tombstones under a shady tree.

Welcome to Jon Cooper’s Battlefield Tour of Cemetery Hill aka Bukit Brown Cemetery. The 2 hour tour’s main route takes you mostly along side the greens of one of Singapore’s most exclusive private golf course and club. As Jon paints a picture of the battleground -literally the blood sweat and tears – I gaze out at the golfers blissfully unaware the ground they are strolling was once a battlefield. But I am moving ahead of the tour here.

The view which sets the geographical location of the battleground, now imagine it wild and green (photo Bianca Polak)

Heritage marker which I reckon only gets a passing glance from bus commuters and joggers in the area ( photo Bianca Polak)

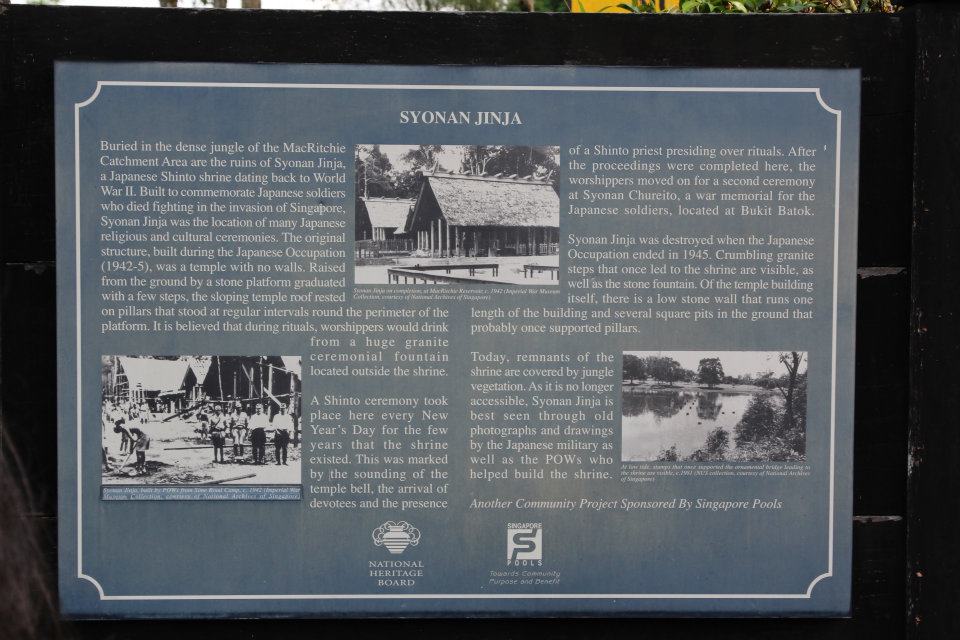

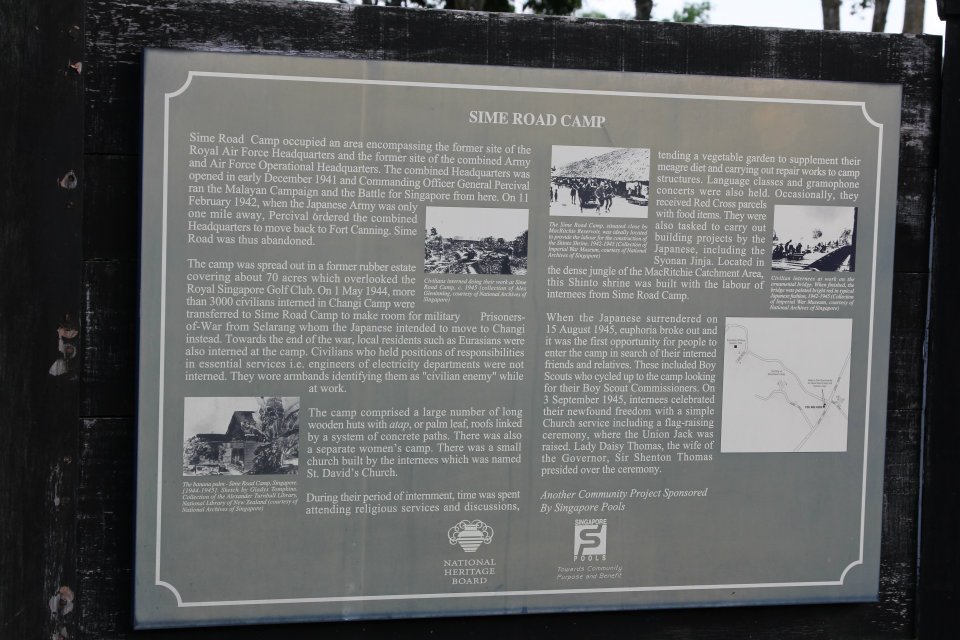

The Shinto Shrine which British POWs helped to build for the Japanese, traces of which are still at MacRitchie Reservoir but off limits to the public (photo Bianca Polak)

Turning into Sime Road SICC, on the left beyond the tall hedges Seh Ong Cemetery (photo Bianca Polak)

Much safer to walk on the soft greens as this mother and daughter team demonstrate (photo Claire Leow)

Third stop 64 Sime Road – The ideal Command House for the British before the war, but there not enough time to consolidate before the Japanese was upon the area (photo Bianca Polak)

Postscript : 64 Sime Road. Post-war building, known as ‘Air House’, official residence of the ‘Commanders-in-Chief and Commanders of the Far East Air Force from 1949 until November 1970’. Far East Air Force was FEAF (pronounced Fee-Eff). HQ FEAF was here in Singapore, the area of operations was from the east of Ceylon to the Solomon Islands in the Pacific, north to southern China and south to East Timor.

Under the shady tree outside number 64 Sime Road, Jon continues the story of brave men from both sides and the battle they faced (photo Claire Leow)

Jon’s most diligent student, he had already been on Jon’s Curator’s Tour of the Adam Road project which was held at the NLB (photo Claire Leow)

And the unexpected surprise of this tour, the caretaker on his own initiative decides we should be let into the ground of number 64 after observing we had been there for some 20 minutes ( photo Claire Leow)

An unexpected bonus for Jon as he is reunited with the insignia of his regiment top row (photo Claire Leow)

Inside, workers who have been maintaining the house, which we suspect will be up for rent soon (photo Claire Leow)

The Group photo, all thought this would make a marvelous war museum for Adam Park and wondered how much was the rent (photo Claire Leow)

As we continued to our fourth stop, from where we stood, we saw this idyllic scene (photo Bianca Polak)

It was here, a 100 metres opposite no, 64 (back on the road heading back to Lornie Rd) under the by now scorching sun that Jon showed us the lay of the land and the battleground ahead at Bukit Brown (photo Claire Leow)

Here is an extract of the battle on the evening of 14th Feb 1942 from an earlier post

The gunners’ targets were the men of the 4th Suffolks, a fresh-faced territorial battalion of the 18th Division who had only landed in Singapore two weeks earlier. The Suffolks, raised from the country towns and farming communities of East Anglia, had already seen combat up at Bukit Tinggi and had been forced to retreat back towards the Lornie Road by the relentless drive of the IJA’s elite 5th Division. The Suffolk’s hasty withdrawal and the stubborn defence of Adam Park by the 1st Battalion Cambridgeshires had allowed the men to establish new positions overlooking the eastern end of the SICC golf course and southern tributaries of the MacRitchie Reservoir. They were all that stood between Yamashita’s army and the all important water pumping stations at Thompson Village and Woodleigh. That evening Yamashita’s exhausted and battle weary troops were to launch one final effort to break through to the east. The leading units of the 11th Regiment of the 5th Division were by now running short of ammunition and artillery shells and the bombardment and attack was to be their final assault. It was to be a ‘make or break’ attack on the hills of Bukit Brown.

At dusk the 3rd Battalion, 11thRegiment led by Colonel Ichikawa surged up the Sime Road and charged across the Lornie Road. Colonel Shimada’s tank company parked up on the fairways of the golf course provided covering fire and his men witnessed the arms and legs of the defending Suffolks fly up into the air with every explosion. He watched as the screaming infantry disappeared into the murk and smoke along the tree line on Hill 130 then to his relief saw the torch lights and flares signal the successful capture of the temple complex. The attack had been a total success; those Suffolks that had not fled or been blown to bits by the barrage had been bayoneted in their trenches. The way was open to Thomson Village; surely Singapore would now surrender.”

The tour continued back to the main road where the group cut through a jogging path in the nature reserve for the most visible evidence of war.

And you have to watch where you are going in case you fall into this hole which will fit a man “comfortably ” (photo Bianca Polak)

This young chap seems to be charging ahead with gusto for the next leg of the tour (photo Claire Leow)

Here, Jon gets a break while BB volunteer guide Claire Leow explains some of the features of a Chinese tomb. This one is the largest single occupant tomb belonging to Onn Choon Neo. The soldiers would probably have found this useful (photo Bianca Polak)

But Jon explains how scary this terrain must have been to the Suffolk boys. Yes they could hide, but bullets could ricochet of the stones and they were be hit, If they decided to make a run for it, they face the swords of the Japanese. It was a grim prospect (photo Catherine Lim)

This was our own Ms G.I. Jane who lasted the whole tour but there was one last stop! (photo Claire Leow)

Our final “resting” place. There used to be a temple here which Colonel Ichikawa had spotted from way across the golf course which was the target of his capture. (photo Claire Leow)

If you want to know what Jon’s parting words to us was, look out for the next Battlefield at Cemetery Hill Tour , hopefully at the end of August. It’s not a difficult terrain to traverse and as I said the main route is pass the golf course but it is hot and humid. Jon is a passionate war archaeologist who with his team has uncovered intimate details about the men who fought in this battle on both sides of the divide . He draws you into the theatre of war with much verve, is great with kids and I was captivated (no pun intended!)

About Jon Cooper : He is an expat, a graduate from the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology at Glasgow University. He has spent the last three years working as the project manager alongside his partners in the Singapore Heritage Society and the National University of Singapore, for The Adam Park Project; a study into the archaeological record of the battle for the estate and the subsequent POW camp that was established there in 1942. The project’s findings r went on show at the National Library in an exhibition entitled ‘Four Days in February earlier this year. The exhibition is now over. and Jon reports, some of the exhibits has had to be stored in his home, where his sons have tremendous fun with their own battle ground”

DR Lim Hock Siew: The Role Model

by Lim Chin Joo

Among the tombs affected by the Government’s decision to exhume Bukit Brown Cemetery to make way for roadworks is that of See Tiong Wah, the grandfather –in-law of Dr. Lim Hock Siew.To find out more about the story, Seah Shin Wong and I visited Dr. Lim at his new house in Joo Chiat Terrace on 12th April without any inkling that it was to be our last meeting with him!

Their living room was still in a mess, yet Dr. Lim was glad to see us and , together with his wife Dr. Beatrice Chen , had a nice chat with us . See Tiong Wah was born to a prominent peranakan family in Malacca in 1885. He came to Singapore when he was six years old to study at St. Joseph’s Institute. After he started work as a bank officer, he rose through the ranks to become a comprador of HSBC. He was an active member of the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce, was appointed as a Justice of Peace, and held the chairmanship of the Hokkien Huay Kuan and Thian Hock Keng Temple for several terms.

See Tiong Wah’s daughter, Lucy Chen nee See, was the mother-in-law of Dr. Lim. Lucy studied law in England in her youth and it was then that she met a young engineering student from Hebei, Chen Xu, who was the son of a key Kuomintang military and political figure, Chen Tiao-yuan. Lucy beacme the first female in the history of Singapore and Malaya to be both raised to the bar as a solicitor in England as well as being accepted into the British Law Society. She married Chen Xu after graduating and returned to Nanjing with him. She gave birth to Beatrice and her two younger brothers soon after. At the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Lucy brought her children to seek refuge in Singapore and stayed with her grandfather, See Tiong Wah, at No. 23 Balmoral Road. The nearby Ewe Boon Road was in fact named after her great grandfather, See Ewe Boon. Beatrice was only 5 years old when she entered Primary One at Nanyang Girls’ Primary School. See Tiong Wah passed away before the fall of Singapore.

Back in China, the Nationalist government was forced to retreat to Chongqing then. Knowing that the Japanese would advance into Southeast Asia (Nanyang), Beatrice, her brothers and their mother Lucy journeyed from Penang to Rangoon by boat, trekked along the Yunnan–Burma Road before reuniting with Chen Xu in Chongqing. At the end of World War II, the family moved back to Nanjing.

After the Chinese Communist Party got into power In 1949, Chen Xu followed the Kuomintang’ troops in their retreat to Taiwan, whereas Lucy would return to Singapore to practice law. Meanwhile, Beatrice entered Hong Kong University to read medicine and graduated in 1958 before coming back to Singapore to work in the Singapore General Hospital.

Beatrice met Dr. Lim Hock Siew at the Singapore General Hospital, and was deeply impressed with his selflessness, his professionalism, gentlemanly demeanour, sense of humour, and firm conviction in his beliefs. On the other hand, Dr. Beatrice Chen cut an elegant figure with her solid bi-cultural background and striking charisma. It was therefore hardly surprising that they would soon be attracted to each other.

Dr. Lim recalled that one day in October 1961, he gathered a dozen of his close friends, including Lim Chin Siong, S Woodhull, James Puthucheary, Poh Soo Kai, Lim She Ping DR Bakar and Fong Swee Suan at his home in Campbell Lane for a “meeting”. It was not until everyone’s arrival that he disclosed that the “meeting” was in fact called to announce his marriage with Beatrice! Dr. Lim jokingly said to us that his mother in law was then not too happy to have a left-wing politician as his son-in-law! Soon after that, their first and only child was born in 1962.

In February 1963, Dr. Lim was detained under the so-called “Operation Coldstore” and was released after nearly 20 years in captivity. Torn apart for decades not long after their marriage , the cruelty inflicted upon the young couple is unspeakable and the untold sufferings would have scarred them for life. Despite all these the couple remained undaunted and committed to each other. Together they went through thick and thin. They are the role models. Their story will go down in history as one of the most glorious chapters in the fight for democracy and freedom in Singapore and Malaya.

At our meeting on the 12th April , we made a date with Dr. Lim to have another chat , but, alas! it is now never to be. What regrets!

This essay was published in the book “Remembering Dr. Lim Hock Siew – OUR FREEDOM FIGHTER” and is reproduced here with the kind permission of Lim Chin Joo

The tomb of See Tiong Wah which is” staked” and affected by the 8 lane highway to be built at Bukit Brown is a “must see” during public tours (photo: Claire Leow)

For more on features of See Tiong Wah tomb please click here

For location and more photos, please click here

The Peranakan Trail was customised for the Peranakan Association and guided by Chew Keng Kiat, Peter Pak and Gan Su-lin. This report was documented and contributed by Gan Su-lin.

A group photo by which to remember the Peranakan Association of Singapore’s visit to Bukit Brown. They reported enjoying the learning journey and the Brownies had lots of fun too (photo Gan Su-lin)

Lovely overcast and breezy day for a guided visit. Today’s tour for the Peranakan Association of Singapore took in the graves of Peranakan pioneers who have left legacies through their own commercial, political, or social endeavours, or the efforts of the illustrious descendants they produced (photo Gan Su-lin)

First stop, Mrs Tan Cheng Siong, the grandmother of current President of Singapore, Tony Tan Keng Yam. (photo Gan Su-lin)

Visitors were particularly impressed by the tomb photo of Mrs Tan Cheng Siong; minimally degraded after many decades of weather exposure. (photo Gan Su-lin)

Brownie Peter Pak regaling the visitors with an explanation of tomb brickwork while waving sprigs of Piper sarmentosum and Murraya koenigii leaves used in Peranankan cooking . (photo Gan Su-lin)

One of the rewards of Brownie work is reuniting descendants with their long-lost forefathers. Cheong Koon Seng’s descendant in a quiet moment at the Koon Seng cluster of grave (photo Gan Su-lin)

More on Cheong Choon Seng here

Keng Kiat introduces the visitors to Tan Yong Thian, pioneering distiller of the essential oil, patchouli. They marveled at the tomb restoration work undertaken by grand-daughter, Brownie Tachi (大姐)Rosalind Tan. (photo Gan Su-lin)

Visiting Khoo Kay Hian, pioneer stock broker was an opportunity to see first-hand a different grave design and style. (photo Gan Su-lin)

“If you look over there, you’ll see we’re now on a hill. You’re looking down the hill.” As it does with many visitors to BB, the intricate tomb carvings on the See Teong Wah cluster of tombs drew admiration and appreciation. (photo Gan Su-lin)

En route to visit Municipal Commissioner Tan Kheam Hock, after whom Kheam Hock Road is named. Another note was made of graves with re-buried (photo Gan Su-lin)

Find out more on Tan Kheam Hock here

A visit was also made to the Tan Keong Saik quartet of tombs. In the foreground, Baba Peter Wee makes an offering of fragrant flowers onto the tomb mound of his grand-uncle, Tan Cheng Tit. (photo Gan Su-lin)

Peter gets cosy with the famous painted Sikh guard at Chew Geok Leong’s tomb. Lessons were learned about living tombs. (ohoto Gan Su-lin)

Find out more on what is a live tomb here

Brownies are always learning! Today, our Peranakan visitors helped us notice that Pang Cheng Yean’s double grave is flanked by that of his mother and of his wife’s mother. (photo Gan Su-lin)

Find out more on Pang Cheng Yean who was a pioneer banker here

Footnote: Customised tours on request can be considered for organisations at a suggested honorarium which goes to defraying expenses for outreach activities. Please email a.t.bukitbrown@gmail.com. All public tours are free of charge.

Dateline : 26 Tuesday 7-pm – 9.30pm

The Ngee Ann Kongsi auditorium of the sprawled out spanking new campus of University Town, NUS fills up. The event: “Moving House” jointly organised by NUS Museum and All Things Bukit Brown. The highlight: a timely resurrection of an award winning documentary by film maker Tan Pin Pin. “Moving House” made in 2001 which followed the Chew family , one of 55,000 Singapore families forced to relocate the remains of their relatives to a columbarium as grave sites made way for urban redevelopment. The screening was followed by a presentation by Dr Hui Yew Foong on the first exhumation documented at Bukit Brown on 3 June 2012 by his team which also included a video clip of present day descendants at the grave of their ancestors. It was a reprisal of a poignant scene from Pin Pin’s Moving House 11 years ago to the present which struck a chord with Judith Huang who was in the audience, and moved her to write in her blog about matters of national importance the morning after. We reproduce it here with her kind permission

Matters of National Importance

For most the glittering success of Singapore is like a mirage, can see but cannot touch. – a friend

I consider myself a patriotic Singaporean, and have been since I was a small child. Perhaps it is a quirk of my character, a function of being unusually enthusiastic about group identities, or perhaps I am just one of those people more susceptible to propaganda. I can’t be sure. But every morning, from the age of 7 through 18, when I recited the Singapore pledge, I meant every word of it (and still do). I still remember this feeling of national pride in progress – particularly economic and technological, that was thick in the air in the 80s and 90s. In particular, when I was in primary school, the object of national pride was the MRT (built in 1986) and Changi airport, both of which featured prominently in any national day poster we would draw for primary school art competitions. There was a sense that this infrastructure, as symbols of modernity and top-of-the-line technology, was part of a national effort to prove that Singapore had a future – or, rather, that Singapore was the future, and that we were all in this together.

The past 5 years saw massive changes in my country’s skyline, population makeup and politics, all of which I am grappling with as a returnee Singaporean. For me something changed when the casinos were opened. I’ve been down by Marina Bay quite a few times now, and I especially enjoyed the iLight festival, where this city really did seem like something out of a scifi movie set, only real. But there is something disconcerting about the fact that our most iconic building is not an opera house, not a national stadium, not a government building, but a casino which bars locals from entering, built for the cynical purpose of milking superrich foreigners to increase the GDP. Can someone who believes gambling is a vice really feel national pride in something like this? I know I feel distinctly uncomfortable when I look at those three slender columns and the ship-like sky garden linking them. Many of my friends from overseas have enjoyed the spectacular view from the top in the infinity pool, but something still restrains me from paying the $20 to enter the sky garden. Somehow, I don’t want my money to go to a company that makes money off other people’s misery and addiction, even if I’m not directly spending it in the casino.

In a week or so another spectacular national development will be unveiled – the supertrees, also in the Marina Bay area. I’m a little more enthusiastic about these, since they also appeal to my geeky side. The supertrees cost $1 billion, and are touted as an amazing man-made imitation of nature, a leap forward in ecological architecture. While I will definitely be checking them out, I can’t help but contrast the construction of the supertrees with the destruction of Bukit Brown, a natural secondary forest, rich in biodiversity, where human heritage and ecology mingle seamlessly.

While watching the screening of Tan Pin Pin’s documentary Moving House at NUS yesterday, I was hit viscerally by the high human cost of national development. The sight of aunties and uncles praying to their ancestors for forgiveness before plunging their hoes into their parents’ graves, the half-curious, half-fearful peering into the grave to see the blackened, shrunken bones of the loved ones they buried some twenty years ago, and the uneasy feeling that their ghosts may be unhappy at these developments were both difficult and fascinating to watch. I think we Singaporeans are no strangers to “sacrificing the small me to complete the big we” (牺牲小我,完成大我). The sort of boh-pian stoicism, the black humour in the “can’t be helped, government needs your land, sorry sorry” explanations offered to the ghosts, are all deeply familiar and endearing, resignation tinged with the tiny sting of resentment.

But the thing is, we are able to swallow this resentment as long as we see the point of the sacrifice. The danger comes when national development is seen to be benefiting not citizens as a whole, but a small, privileged group, which, furthermore, may not even be primarily Singaporean. Yes, the supertrees will be open to the public – the $1 billion is not going to finance a private garden. However, they are located in the Marina Bay CBD area, enhancing the million-dollar views of the skyscraping buildings and condos in that region, and I’m willing to bet that the average heartlander will probably not make the trip down to see them all that often. Bukit Brown, on the other hand, is a far more humble site, though occupying some pretty prime land (next to the exclusive Singapore Island Country Club). It is a sacred site for veneration of ancestors, a rich source of historical information as well as biodiversity. Furthermore, its destruction (and so, the loss of historical memory) is irreversible – it’s not as though we can simply transplant the gravestones somewhere, or preserve the material culture without destroying it.

The truth is that much of the frustration I sense from the people who have relocated, exhumed graves, or had their land repossessed for the sake of “national development” is that simply not enough information is given to explain why their sacrifices matter, and, crucially, what they (and people like them) are going to get out of it. In other words, the cost-benefit analysis, while a process transparent to policymakers, is largely opaque to those affected. Perhaps the average Singaporean would be more willing to relocate because an MRT station needs to be built, rather than a highway, since he may see the MRT as a more egalitarian infrastructure project compared with a highway that he associates with cars (which, due to the high cost of COEs, are out of the reach of most Singaporeans).

Funnily enough, I find that now I have returned, my sense of national pride has shifted from the nation-building projects to the amazing growth of civil society I’ve witnessed from afar in the last few years. I am amazed at the volunteer spirit of the “brownies”, the way they have set out to teach other Singaporeans about their heritage and history and ecology. While the building projects are monumental and aspirational, the movement to preserve Bukit Brown’s heritage is nostalgic and humble, but also noble in its insistence that every pioneer buried there matters, and offers a glimpse of life on this island as it once was, a piece of history that, once destroyed, represents a loss to all of us, because our own understanding of ourselves would be that much poorer. The narration of the past is just as important as the building of the future. We are not rootless creatures. Although our nation may be young, each of our family histories reaches as far back into time as anyone else’s, no matter what our nationality, and it is truly up to us to preserve or discard these pasts.

Whatever the outcome at Bukit Brown, what is remarkable about the movement that has sprung up around it is that dialogue has opened up in ways unimaginable just a few years ago. Although activists may say that the government has been unresponsive, and civil servants may be wringing their hands at the unexpected “trouble” activists have given them, the truth is that the level of dialogue and collaboration has far exceeded any other civil society case in recent memory, and this can only be a good thing, as the government learns how to communicate its plans and decision-making processes better, and civil society gains more experience and tools in making the wishes and aspirations of Singaporeans known.

After all, a sense of national identity needs to come from the citizens themselves, rooted in our culture and our history, because in our democratic society sovereignty rests with the citizens, and legitimacy rests with their elected representatives. It is our shared past and our shared future that makes us Singaporean, and if we don’t stand up to define it, no one else will.

Judith’s other pieces on Bukit Brown can be found here and this one was written after her first visit to Bukit Brown

by Gan Su-lin and Catherine Lim

The tomb staked 1888 or rather its companion is used as an illustration in the LTA sign boards at Bukit Brown to explain to the public how to look out for and identify whether an ancestor could be affected by the 8 lane highway that is going to be built through Bukit Brown.

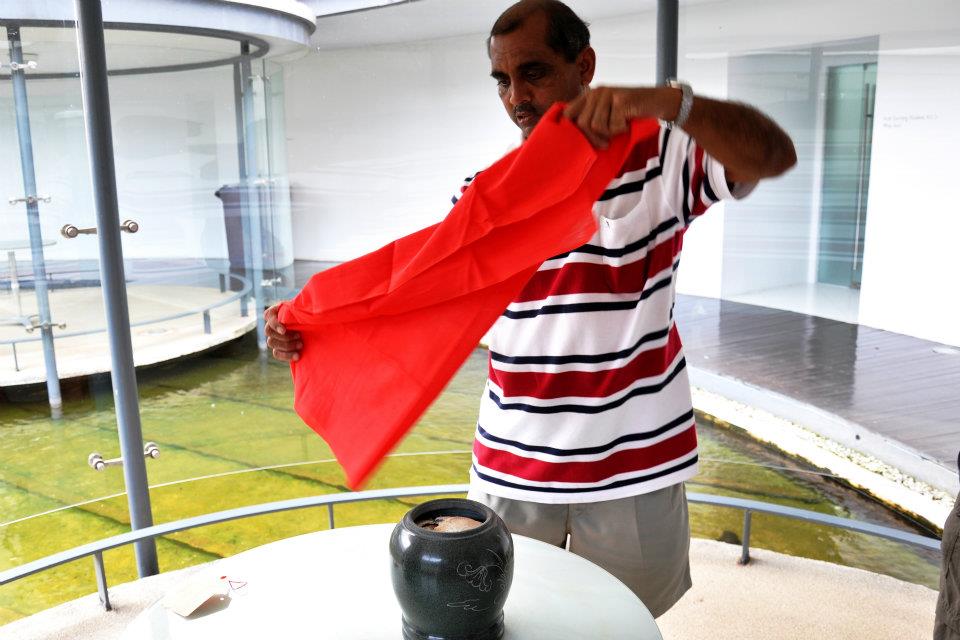

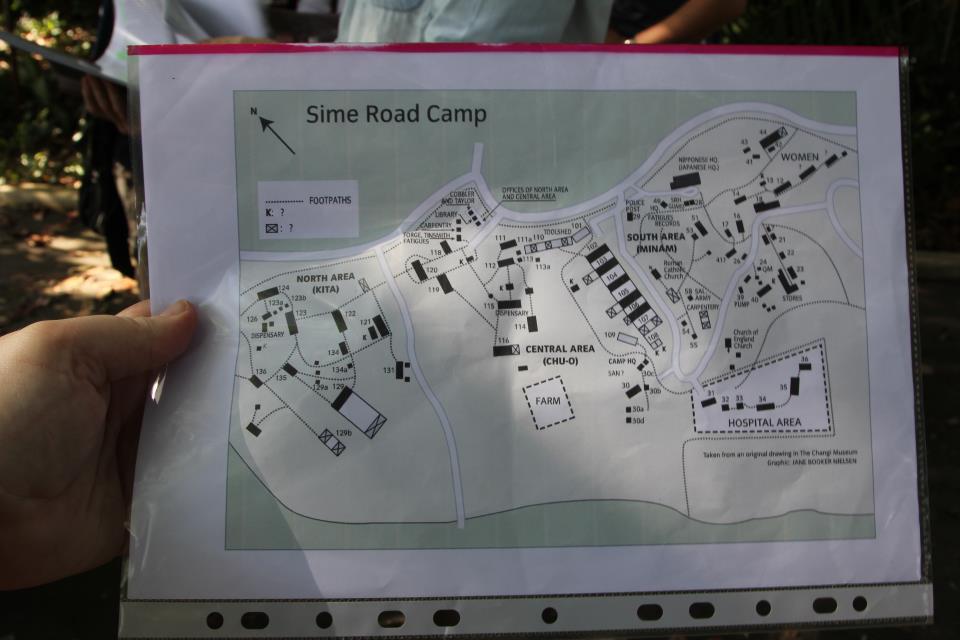

The resident of Tomb 1888 was exhumed on Thursday 21 June 2012 by his descendant, a great grandson who has requested privacy of identity but was kind enough to allow Su-lin and me a chance to document and observe the exhumation from start to end.

On that day, we were told there were 4 exhumations and the following day, 11 were slated. We know this because exhumations has officialdom behind it. They have to be registered with NEA (National Environment Agency) which sends inspectors to spot check that it is conducted properly. There are papers to be signed and processed, but the tomb keepers are familiar with the procedure and cut out as much of the paper work as possible for the descendent. A note here to say that the companion tomb next to 1888 is not occupied which is not uncommon in Bukit Brown. The one beside it was most probably prepared for a spouse but who was not buried there for a variety reasons which we will not speculate on. The descendant was alerted to the existence of his great grandfather’s tomb only last year by Raymond Goh and proceeded to “refurbish” the tomb before news was released that the grave was affected by highway.

The exhumation of staked tomb 1888 started at 8 am with prayers and the digging started about 20 minutes later together with the separation of the tombstone from the backing which is necessary to release the spirit, a way of notifying the “resident”, he is moving house. The latter required the wielding of the mallet against stone which was heart wrenching to observe even for an outsider. The exhumation proved longer than the anticipated one hour because the grave was so well encrypted with granite slabs and brickwork and the coffin so well kept that it required a chainsaw to cut the opening. It was a “clean” exhumation, with remains of bones and nothing else.

Preparing to chant prays with incense, a bell and a dorje or vajra– ” thunderbolt” which is used in Tibetan Buddhism. The brown portfolio is an ipad which had been loaded up with the chants (photo Catherine Lim)

Separating the tombstone from the backing “releases the spirit” notifies the long time resident, he is moving home, the digging starts in tandem (photo Catherine Lim)

A valuable piece of inscription on the lives and times of the ancestor which is saved. (photo Catherine Lim)

Gan Su -lin (who documented) weighs in with Lim Ah Chye (tomb keeper) what to expect. (photo Catherine Lim)

Revealing the coffin, intact and impenetrable after more than 70 years and some excellent brick work that drew the admiration of the grave diggers (photo Gan S-lin)

The first yield is a termites nest which Su Lin picked up thinking it might be the discovery of truffles in Singapore ( photo Gan Su-lin)

The second yield, teacups which survived the long internment, duly collected and delivered to documentation team office (photo Gan Su-lin)

The exhumed ancestor must not be exposed to the sunlight.The use of the umbrella is symbolic and will shade the ancestor right up to the placement at the final resting place The remains were rinsed prior to transfer to crematorium with Chinese wine.(photo Gan Su-lin)

Ah Nan, who speaks fluent Hokkien presides over transfer of ashes to urn with the greatest of respect and meticulous attention ( photo Gan Su-lin)

One last look at the Crematorium before the ancestor was brought to the family temple (photo Catherine Lim)

The exhumation began at 8 am. The gravediggers reached the granite slabs an hour later. The remains were exhumed just after 10am and transported to the crematorium about 10.30. The remains were ready for collection at 11.30am. By 1 pm, the ancestor was” laid to rest” in the family temple.

Luah Kim Kway (赖金奎) the Chivalrous

by Ang Yik Han

On first impression, his is a typical story of a poor migrant made good. Orphaned when young, Luah Kim Kway left for the Nanyang at the age of 19 to seek his fortune. Like other uneducated migrants who toiled unceasingly, he was at various times a coolie, a hawker and a miner before hitting his first pot of gold as a building contractor. Subsequently, he branched out into the rubber and import/export businesses. As a community leader, he was one of the founders of the Chin Kang Association, a locality association catering to Hokkiens from Chin Kang (晋江 – “Jin Jiang” in pinyin) county in Fujian province. He served as the association’s vice chairman for many years and was actively involved in its mutual aid group and school.

Many also knew Mr Luah, or Kway Pek (“Uncle Kway” in Hokkien) as he was respectfully called, as a powerful secret society headman.

A coolie newly arrived in Singapore found himself amongst strangers in a strange land. Very often, there was no one he could trust and turn to for support other than clansmen or associates from his home village. Thus was born the “coolie keng” or coolie quarters which provided shelter, occupational support and fellowship for coolies sharing a common origin. In return for a small sum every month, the coolie had a space where he could sleep and stow the trunk containing his meagre belongings.

Due to the nature of migrant society then, differences were often settled by force of arms and numbers counted. Members of coolie kengs banded together for self protection and over time coolie kengs became synonymous with secret societies. There were frequent clashes amongst rival coolie kengs over turf issues. Some of them even evolved into criminal organisations which were a constant headache to the colonial authorities.

Many of the Chin Kang Hokkiens who arrived in Singapore in the early days worked as lightermen and dock labourers, traditional occupations as their homeland was by the sea. Like coolies from other regions, they were organised along the lines of the coolie kengs they belonged to. According to the Chin Kang Association’s records, at one point there were more than sixty coolie kengs in town set up by Hokkiens from Chin Kang. In areas like Bali Lane, there were Chin Kang enclaves due to the presence of numerous coolie kengs.

The Puah Kor (Hokkien for八股 or “8 formations”) was a confederation of societies largely made up of Chin Kang coolie kengs with a sprinkling of non-Chin Kang groups. Unlike other secret societies which were involved in activities of a criminal nature, the Puah Kor was known for its tight discipline. It did not actively seek conflicts with other groups and acted only to protect its members’ interests. Mr Luah was the leader of the Puah Kor, a position which must have reinforced his ability to arbitrate in conflicts between Chin Kang coolie kengs as well as within the larger Chinese community in his other role as a representative of the Chin Kang Association.

An anecdote demonstrates the extent of his influence. After the war, a Chinese basketball team from Manila composed largely of Chin Kang Hokkiens was in Singapore on a fund raising campaign. For some reason, some factions took a dislike to the team’s captain and there were rumours floating that the coming matches would be violently disrupted. One of the worried organisers took the matter to Mr Luah. Mr Luah only commented in his quiet manner, “Shall we have some fried bee hoon?” During the meal, the conversation ranged far and wide with many things discussed but not the subject of the visit. As the guest was about to take his leave, Mr Luah told him, “Give me sixty tickets for tonight’s game.” That night, two hundred stout men turned up for the game at Gay World which proceeded peacefully. The following evenings were without incident as well.

For obvious reasons, it is almost impossible to obtain documented accounts of secret society personalities. Mr Luah was an exception. His contributions and high regard in society were acknowledged in an obituary published in the Nanyang Siang Pau when he passed away in 1951. It described him as a principled man whom others trusted and mentioned his generosity to those in need. As an epitaph, a phrase used by the paper, “a chivalrous man” (大侠) would be most fitting.

Mr Luah’s final resting place is by the side of the road in Hill 3, a short distance from Tan Chor Lam’s grave.

References:

- 新加坡晋江会馆纪念特刊(1918-1978)[Commemorative Publication, 1918-1978]

- 新加坡晋江会馆庆祝成立80周年暨互助部成立52周年纪念特刊 [80th Anniversary and Mutual-Aid Section’s 52nd Anniversary Souvenir Magazine]

- Interview with Ho Bee Swee, Collection of Oral History Recording Database

Seh Ong Hill

Introduction

The Bukit Brown Cemetery Complex mapped out by Mok Ly Yng based on the land lot tracings from this map shows a surviving area of approximately 390 acres. The biggest Chinese cemetery outside of China consists of four identifiable cemeteries bordering each other : Bukit Brown, Lau Sua (Old Hill), Kopi Sua (Coffee Hill) and Seh Ong Sua (Ong Clan Hill) This map shows the various cemeteries demarcated

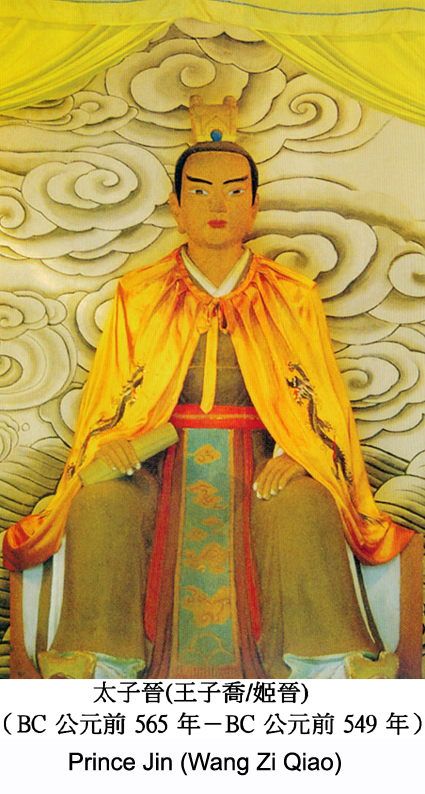

In the following article Jave Wu traces the link between Seh Ong Sua (Ong Clan Hill) and the origins of the Hokkien Ong Clan way back to dynastic China, 550 BC. Jave researches & consults in Chinese culture, history & religion, specialising in Taoism.

Seh Ong Sua and the Hokkien Ong Clan (星洲姓王山與開閩王氏)

By Jave Wu

Seh Ong Sua is also sometimes known as “Tai Wan Sua” in Hokkien. “Tai Yuan Shan” (太原山 pinyin: Tàiyuán😉 refers to the capital and largest city of Shanxi Province in North China. )

The connection began in the late Zhou Dynasty when the first ancestor of the Ong clan, Prince Jin (太子晉), also named Wang Zi Qiao (王子喬/姬晉), was stripped of his royal status by his father King Ling of the Zhou (周靈王) in 551 BC (周靈王廿二年).

Born in 565 BC, Prince Jin was supposed to be a descendant of the Yellow Emperor (黃帝). He was a precociously intelligent child who often offended his father because he was given to speaking out in the face of his father, King Lin’s stubbornness and lack of wisdom.

During a morning assembly of the Court, King Ling suggested an impractical method of dealing with the frequent flooding in the kingdom. Prince Jin was about 14 or 15 then and he objected to his father’s suggestion in front of the other court officials, which placed King Ling in an awkward situation. Outraged, the King stripped Prince Jin of his royal title. The Prince was disappointed and foresaw the collapse of the Empire. He suffered from depression for 3 years before passing away in 549 BC at the age of 17, leaving behind his wife and a young son, Ji Zong Jing (姬宗敬).

Soon after Prince Jin’s death, King Ling also departed the mortal world. Prince Jin’s younger brother, Prince Gui (太子貴), ascended the Zhou throne as King Jing (周景王). At a young age, Ji Zong Jing was appointed as the Premier (大司徒 – 相等丞相之職) by his uncle King Jing.

Well aware that his uncle was an inept ruler like his grandfather, and seeing that the Empire was collapsing, Zong Jing resigned from his post and left the Imperial court, escaping to Taiyuan City (太原市) in Shanxi Province (山西省) to take refuge. To avoid being recognised, he changed both his surname & name.

As he was a descendant of the Imperial family, he used the Chinese character “Wang” (王 = king or “ Ong” in Hokkien) in place of his actual surname “Ji” (姬), and changed his name from “Zong Ji” (宗敬) to “Rong” (榮). Henceforth, he was known as Wang Rong (王榮), symbolising the royal lineage will be “prosperous & continuous.”

The Wang clan took root in Taiyuan City and the descendants multiplied over the generations. By the Tang Dynasty, there were many people with the surname Wang (Ong) all over the Middle Kingdom (中原). As a result of this historic beginning, those of the surname Wang (Ong) refer to Taiyuan as their place of origin. This also explains how the name of Taiyuan Shan in Singapore came about.

From 615 to 755 AD, after the rebellion by An Lushan (安祿山), southern China (especially the Fujian area) was in turmoil with constant strife between warlords. In 885 AD, 3 brothers, Wang Chao (王朝), Wang Shenzhi (王審知) & Wang Shenggui (王審邽) recruited an army which drove into southern China and brought peace to the troubled region. To protect the common peoople from further suffering, the three brothers built a kingdom in Fujian which came to be known as the Min Kingdom (閩國). The establishment of the Ong clan in southern China could be traced to this victory.

During the late Ming & early Qing Dynasties, many Hokkien Ong clansmen left their homeland in Southern China for Southeast Asia. By the late Qing Dynasty, their descendants had settled in many parts of Southeast Asia including Singapore.

In 1872, the members of the Hokkien Ong clan in Singapore decided to have a place where the living could reside and where their departed ancestors could be buried. Three of them, Ong Ewe Hai (Wang You hai 王有海), Ong Kew Ho (Wang Qiu he 王求和) and Ong Chong Chew (Wang Zong zhou 王沧洲 ) contributed $500 each to buy a plot of land between Toa Payoh and Bukit Timah, approximately 97 acres which was to become Seh Ong Hill (姓王山)

Soon after the cemetery was established, the three good friends proposed building a temple there to honour the first ancestor of the Hokkien Ong clan, with the assistance of other clan members. This was the “Temple of the King of Min” or Min Wang Ci (閩王祠). After the temple was constructed, Wang Youhai (王友海) set off for Fuzhou in Fujian Province in China (中國福建省福州市), where he brought back the ancestral urn and paintings of the three Wang brothers who established the Min Kingdom from Zhong Yi Wang Temple in Qing Cheng Si Street (慶城寺街忠懿王廟).

In 1875, the Hokkien Ong Ancestral Temple (閩王祠) was set up to assist Hokkien Ong clan members. In 1944, the name of the association was changed to Hokkien Ong Temple General Association (閩王祠公會) and in 1970, this was changed again to Singapore Hokkien Ong Clansmen General Association (開閩王氏總會).

From 1982 to 1990, the land around Seh Ong Hill was developed and some vacant land was acquired by the government. Using the compensation which amounted to approximately 9 million dollars, the clan bought a piece of land in Bukit Batok Street 23 where the Hokkien Ong Clan Temple was rebuilt. The construction was completed in 1999 and then President Mr Ong Teng Cheong was invited to be the Officiating Officer for the grand opening of the new temple on 2 May 1999.

Till today, the Hokkien Ong clan still conducts annual ceremonies for the Spring and Autumn honouring their ancestors in Singapore and as well as in China. it allows the clan to remember the credit & merit they had accumulated in building the “Hokkien Ong Kingdom”

“The trees have roots, and the water, its source.”

Dedicated to the Ong clan & its ancestors

References:

http://bukitbrowntomb.blogspot.com/2011/11/blog-post.html

History of Clan Associations in Singapore Vol. 2, SFCCA 2005.

One Hundred Years’ History of Chinese in Singapore 新加坡华人百年史。

For more of the Ong connection at Bukit Brown – http://bukitbrown.org/a-great-hill-for-us-to-remember and A Grand Repose.

Recent Comments