9th February, 2024

The Year of The Dragon – The Cusp of a New Cycle

“January 23, 2012 to February 9, 2013 marked the Year of the Dragon. According to tradition, the dragon is the fifth animal in the Chinese zodiac and symbolizes loyalty — it is noble, gentle, and intelligent, but also tactless, stubborn, and dogmatic. “ New York Public Library

2012 was the year a nascent community from different disciplines and interests – IT engineers, journalists, a pharmacist by degree, a librarian, academics, artists, teachers, students, nature lovers, heritage proponents, authors, film makers, lawyers, the tomb keepers, the former residents of the Kampong at Lorong Halwa, a cartographer, descendants of the stones and the local and international media – emerged, each to play their part in generating awareness that there is this 100 year old municipal cemetery called Bukit Brown, that sits in the center of our island where the stones tell stories of the past and the flora and fauna breathes life into it. And the government wanted to build an eight lane highway that will cut Bukit Brown in half, cleaving apart 100 years of heritage, habitat and history.” It is a rare original WWII site that saw one of the last and fiercest battles on the rolling hills of the land.

Chapter I: How it began…..

The first official engagement with the government under the Ministry Of Development went badly. While the Minister was abroad, his senior civil servants were engaging with civil society on a date to meet him. We wanted a consultation and an opportunity to ask what were the alternatives that had been considered.

By the time a date was found – it took about three weeks – the circumstances of the meeting had changed. First there were “outsiders” those in heritage circles but Bukit Brown was not necessarily a priority. This was not the scenario we had envisaged when we met at the Nature Society’s HQ at Geylang. We came from roughly seven different organisations/communities including one newly minted, all things Bukit Brown, feeling their way in tentative steps through civil society.

The response to the meeting or more accurately the briefing by the then Minister of National Development was an immediate media statement calling for a moratorium on the roadworks signed by The Nature Society of Singapore(NSS), The Singapore Heritage Society (SHS), Post Museum, Green Drinks, The Rail Corridor, API, (paranormal group) and all things Bukit Brown.

Both NSS and SHS had led the email negotiations to pin down a date and an agenda to bring up to the Minister. And the way the emails were going, we knew that was a 99 percent chance, we would not get the meeting we requested. Instead the Minister announced the plans from exhumation to construction of the highway in a PPT, with a concession that the whole process would be documented. A suggestion that a heritage advocate had suggested to the CEOs of URA & LTA when they invited him for a morning prata to ask his opinion. It was indeed a prata flip. Aside from the seven groups, there were heritage bloggers, representatives from clan associations, The Peranakan Association government agencies, , the Preservation of Monuments Board and the National Heritage Board.

The fact that seven groups from civil society including the two most established the nature and heritage societies, issued a statement disagreeing at the haste the decision was reached without genuine consultation, made headline news. Bukit Brown was after all, one of our oldest Chinese cemeteries and the mother of all cemeteries with many remains reinterred there because of major developments where they were first laid to rest. Their burial grounds , had made way for HDB estates such as Queenstown, and so in the past time and time again, the dead had to make way for the living. This was different, an 8-lane highway. In today’s context with climate change a critical and existentialist issue, questions would have been raised why are we encouraging car ownership? Could nothing be done with the then Lornie Road, only eight years in existence ? They were raised then, almost prescient. Back and forth, like a ping pong game, with the ball falling into the government’s side of the table in a staccato volley. We were called naysayers, unsympathetic to motorists and asked to offer solutions to solve traffic jams.

Then the government announced that they had taken on feedback and as a concession to civil society realigned part of the highway as a bridge. It was the most natural of realignments as the previous plan would involve building the highway into a valley. What had happened was that the Nature Society of Singapore had submitted the proposal independently to allow space under the bridge for animals to pass and shady plants that did not need much sunlight, It did save a few graves from certain “death”. The concession by the authorities was much lauded in the media as an indication that the government of the day was not recalcitrant and was responsive. With that, the first chapter of our journey came to a close.

Chapter II Letting Go……

Two communities, Post Museum and all things Bukit Brown moved on and forward, to continue to conduct public guided walks to spread awareness, the latter community branched into themed walks such as World War Two at Bukit Brown hooking up with a war archaeologist from the UK, whose family was stationed in Singapore because of his wife’s career. He had found himself living on the doorstep of the battleground around the black and white houses in Adam Road and later explored the Mount Pleasant black and whites the Japanese had occupied. He started to conduct WWII guided walks detailing battlegrounds that covered the Island Club links into Bukit Brown proper including the names of soldiers who are still missing and their last known locations. Their remains may very well lie under the highway – grist embedded in the concrete – even as their names are acknowledged at the Kranji War Memorial.

Outside of Bukit Brown, Post Museum which is an arts group helmed by a husband and wife team, secured a grant for an exhibition held at SAM, the Singapore Art Museum. They were to curate other exhibitions at the Substation and the exhibition space in Bencoolen Street of La Salle College. And they have taken the Bukit Brown “index” to the USA. Days before the exhumation exercise was to start, they arranged a candlelight remembrance and lit up the entrance into Bukit Brown. That entry into the cemetery is no longer, absorbed now into the Lornie Highway.

Particularly poignant in Post Museum’s first exhibition at SAM was an installation where the names of the deceased who had to make way for the highway were written in chalk on a big wall by volunteers and the public, with a photo collage of some of the volunteers at their special/favourite spot in Bukit Brown. The GOH for the opening was Ms Jane Ittogi, the present First Lady who was Chairman of SAM then. Ms Ittogi was to later be the GOH for a brownie event, – brownies, that’s how the community of volunteers under the banner of all things Bukit Brown are known to the public. It was to be a much bigger event over a weekend with exhibitions of artifacts including a letter written in romanised Hokkien, presentations on nature and heritage, and a screening of a documentary, Light On Lotus Hill about the efforts here to assist in logistics in support of the Sino-Japanese war. It was a collaboration with the Chui Hway Lin Teochew Club. It followed very soon after atBB also curated the first exhibition at The Substation partnering the Singapore Heritage Society and the Sub. In the meantime, an 8 part TV series called “History from the Hills” debuted with Bukit Brown as the central space, telling the story of Singapore from pre colonial times to independence. It was to be dubbed into both Mandarin & Malay in years to come.

Along the way, the new kid on the civil society block, picked an award from the inaugural Singapore Advocacy Awards celebrating the best and most promising in civil society. It was more than encourage, it sealed, resolved.

But it was the international media who took up the gauntlet to source alternative views, different angles to the issue The BBC, CNA, and Reuters had correspondents based here. Brownies were interviewed on air and quoted in print. They sent in questions to the government but they had no comment. The Economist correspondent and the family of husband and wife with one young son and a mangy and lovable Singapore special lived near Bukit Brown. They treated Bukit Brown as their backyard and had joined the brownies in their explorations, “bush bashing “ together in areas tight with above and under growth. He blogged it in The Banyan. A Singapore artist and former photojournalist with the local media and her partner, a Pulitzer prize winner for journalism who flew in from New York for the Singapore Writers Festival, arranged to visit the site with brownies and an academic in tow, and somehow managed to gained access to the storage where the tomb artifacts of exhumed graves were stored and snapped a few choice photos. And so that was how Bukit Brown Cemetery and us found ourselves in The New York Times in a feature article.

Chapter III Gaining Traction & The Message in the Bottle

“People with Chinese zodiac dragons born in 2012 have great vision and ambition. In addition, they are full of patience and persistence. Therefore, they can achieve success in their career field easily. They are bold people full of justice and energy, and they like to help people who are in trouble. They have good interpersonal relationships, because they care about friends carefully. They have a unique style and can give everyone an interesting chat when they are in a low mood.”

We are not sure that accurately describes the community but time has proven we are patient and persistent. An application was made to the World Monuments Fund, to have Bukit Brown Cemetery recognised as a historical and heritage site under threat from an impending highway. We got it, the first site in Singapore to gain this recognition. It was for two years 2013 an 2014. When the news broke, most of us were at a temple dinner.

We held a media conference in Bukit Brown and had fairer coverage. Meetings followed with the National Heritage Board, there was to be no u-turn for the highway, so we simply went with tapping grants from the Board, and the result was a book, WWII@Bukit Brown launched in 2016, an anthology of stories with contributions from heritage enthusiasts who charted the military movements from both sides of the divide. And the brownies themselves shared stories they researched and encountered on the grounds of Bukit Brown. But the heart of the book were stories from the descendants whose young men had been taken away by Sook Ching – and the equivalent of a pogrom. It also included other tragic deaths, the story of how an elder sister and also an aunt, was killed by shrapnel from a bomb, protecting her mother, a younger brother and a niece. She was only 19 years old, with a steady boyfriend. The chapter was called “ Lost Promises” And that was exactly what WWII had wreaked on the island, a palpable loss.

We followed the book with Wayfinder@BukitBrown, a curated trail with directional signage and information boards for graves both prominent and poor in easily accessible areas, by pathways and areas where descendants clustered around a set of tombs had their tomb keepers maintain the tombs of the ancestors.

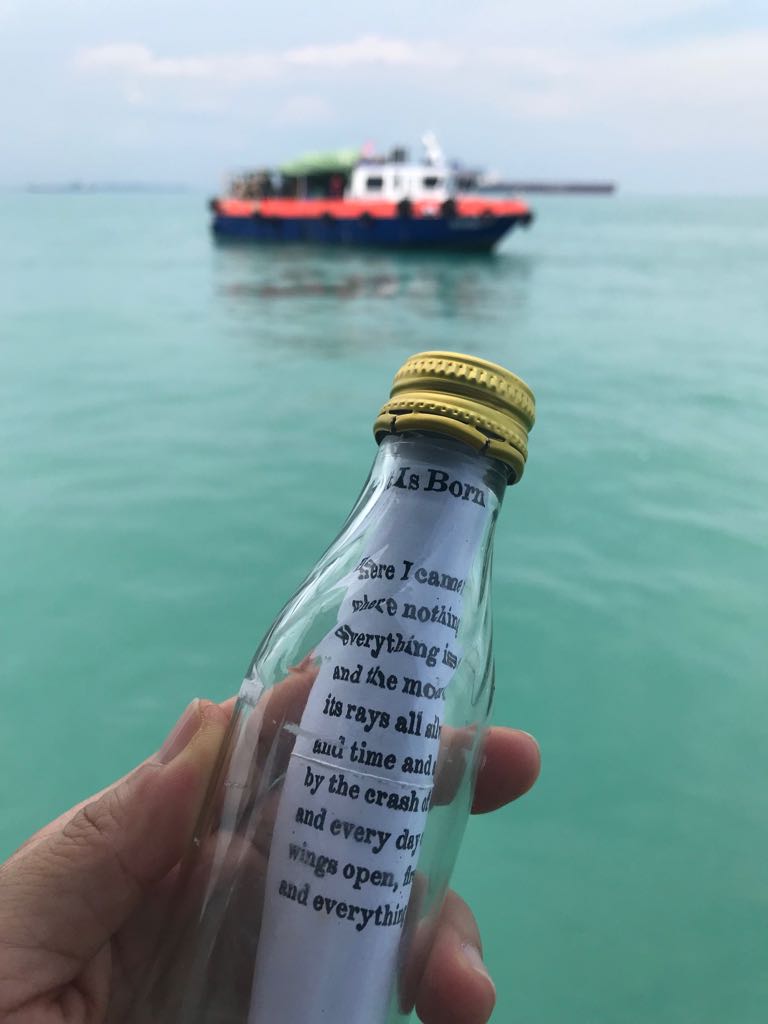

And sometime after Wayfinder was launched, we witness the sea burial of the unclaimed remains of those exhumed for the highway into the waters with a message in a bottle. By sheer dint of fate, a last minute claim was made on the eve by a friend of the brownies, so one less went into the waters. The same waters where their ancestors once sailed through perilous journeys borne by uncertain winds and currents until they reached safe port in “Sin Chew” a sobriquet popularised by the poet Khoo Seok Wan as the “island of stars”; their first glimpse when they arrived at night, the lights from the vessels, necklaced the island. Khoo was himself affected by the highway. The Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall made a claim for his tomb. So he is memorialised, ironically by his tombstone.

Chapter IV It Won’s be to Long, now ……..

IT WON’T BE TOO LONG: THE CEMETERY (DAWN & DUSK) by Drama Box staged as part of the Singapore International Festival in 2016 made a profound and powerful impact on the community, and gave the brownies both inspiration and validation.

Every year, we get requests from students doing their final papers for interviews or to be part of the documentary projects from Mass Comms students, and the occasional foreign media looking to refresh their stories of the country they have been posted to, just how does a cemetery tick the boxes of community, of heart, of a shared and painful past, of rebuilding, of the forging of a new found identity ? Like patchwork the different threads go into a blanket of stories, still being added to.

Over the years, we have received requests to make presentations from the tertiary institutions such as from the LKYPP, the soon to end Yale-NUS, to complement the walks. From schools to community and adventure groups, opposition parties and establishment, we walked with them and guided in a truly inclusive space. So the public guided walks continue to be our backbone even through lock down as we secured permission from STB, through an intermediary who believed in our efforts and had a long standing working relationship with STB. Boy, did we need the fresh air and sunshine, as we breathed maskless. But we were closely monitored for safe distancing and numbers.

We are thankful that all restrictions have been lifted. In the two years of covid, Bukit Brown was “under maintained”, so parts have grown lusher than before. Slowly but surely tho’ regular maintenance is being implemented as before. Not unusual now to see groups of three or four workers cutting the grass by the paths. So is life back to “normal” now?

Now on a Saturday, if you are lucky you may encounter a trio dubbed as “The Three Amigos” which includes a tomb keeper and sometimes a young warrior woman carrying kilograms of water for cleaning and it is said she keeps the amigos honest. Together they explore Bukit Brown and venture into the adjoining cemeteries of Lao Sua, Kopi Sua and Seh Ong, every Saturday and stop only for the CNY and Xmas holidays or when they are away for work or family. Sometimes they have “guests” with them, they are descendants who have requested assistance locating their ancestors. The reuniting of families to their roots is what keeps them grounded and going, bush bashing, recalling mysteries they encountered that now have answers, and they grow our compendium of a past lives brought into the present. Enough for another book, but that’s for the future. This year we consolidate.

We have been walking – walking the talk – now in a complete 12 year cycle of the Chinese astrological animal, the dragon, the one mythical creature among the twelve. Perhaps, there is something symbolic in that, that holds hope and a promise we are closer to our mission to protect Bukit Brown for future generations; descendants are returning to look for their ancestors, to connect with their roots, more young people are researching their family history, as always we “connect” them to their roots and to us, then back to you when we share their stories online in our FB groups, blogs or in our presentations. A virtuous and vibrant cycle.

As we welcome the new wood Dragon, we are in the process of working on version II of WWII@BukitBrown, It has been six years and during this time we have uncovered more stories and new material has been shared with us exclusively on the Japanese battle plan under General Yamashita including his annotations on the maps of what was to become Synona-to. We are grateful we have this exclusive through the generosity of a private, independent researcher of all things Japanese, who has focused on the war years from primary sources.

And we are relaunching Wayfinder, so coming your way is Wayfinder II. More tombs, more areas covered, to be launched with instagram interactivity. We hope to launch phase one covering the original Hills 1 and 3 with add ons by June’24. The designers have done the first two focus groups to find out what worked, what didn’t and what kind of content independent walkers are interested in.

If you have visited Bukit Brown and would like to take part in the next focus group, please contact our designers thestudiosonder@gmail.com.

Subject: Wayfinder II

Information needed: Name, Age, Gender, phone number and Status: student, working, not working or retired. The information is needed to ensure a representative demographic. If there are too many applications, the designers will only be able to contact you if you fit the demographic, and apologies to those who could not be accommodated this time and thank you!

As always on our big projects we bring in the Singapore Heritage Society to work with us, and they will be with us on the book and the wayfinder. On that pragmatic note, all things Bukit Brown would like to bring you back to what the Year of the Rabbit had visited upon the community. It was a year of realigning back to face- to- face meetings with the National Heritage Board who organised a focus group discussion with the Singapore Heritage Society, all things Bukit Brown, the Nature Society, descendants, the inter government agencies with oversight over Bukit Brown and educators. There is something afoot that would be announced, shortly .

Chapter V Farewell 2023 and Welcome 2024

In 2023, we count our collaboration with Temenggong-Artists-in-Residence, our most productive, enjoyable too, when we participated in their Zhong Yuan (aka Hungry Ghost) Festival. On opening night, their GOH was overheard remarking, “this is a living museum” as he gazed upon the grounds of the black and white houses, perched on a hill facing the old port, resplendent with grave artifacts above and below. Twice, he remarked “this is a living museum” Minister, there is one right in the center of Singapore, still vibrant and teaming with nature and humanity.

The country was galvanised by the Presidential elections. Perhaps the community had a soft spot for President Tharman, who had visited Bukit Brown when he was Deputy and Finance Minister then, with the documentation team and all things Bukit Brown. It was one stormy and lighting flashed afternoon when his entourage arrived. He and his wife Ms Itoggi took shelter at a home of a brownie. We were gratified they returned after the storm calmed, and went with the original itinerary covering four out of five hills. We finished late as the skies darkened and there was no light left ‘cept from our phones. And he asked us a question, and that question gave us hope.

So we look towards the Year of The Dragon with hope and our gratitude to you, our supportive community, we greet you with our very best “Huat” wishes, may the wood dragon not breathe fire unto himself! It means, continue your conversations, discussions and debates on Singapore Heritage – Bukit Brown Cemetery, but be polite and respectful, less the Dragon boots you out.

Be safe, be healthy, wealth in terms of currency ain’t what it’s cut out to bring. It is the prosperity and good fortune of living a virtuous life, lending a hand to those in need, looking out for your neighbour, to be kind – these are rewards within themselves. This is what we have learnt from the stones of Bukit Brown, and they have many lessons yet to give.

A guided walk to the rarely traversed hill 4 saw a turnout of 20 enthusiasts, some repeat customers, but the majority were first timers.

Our passing stop was the tomb of Tan Chor Nam, enroute to Hill 4, where Fabian explained the importance of the man who was the founder member of the Tong Meng Hui, the revolutionary arm of Sun Yat Sen, widely acknowledged as the founder President of the Republic of China.

At Hill 4, we had to abandon visiting the Tan Quee Lan cluster, because the route was cut off by too many fallen branches.

And so we proceeded to the Lim cluster to Chong Pang and his story of escape by sea during WW2, ship sunk, fortunately he was rescued, but unfortunately found himself back on the island, forced to serve in the Overseas Chinese Association, (OCA) which was essentially the Japanese propaganda machinery.

Much vilified by his own, was he like Lim Boon Keng who served as head of OSA, vindicated, after the war was over? Join us at our next guided walk to Hill 4 to find out and also find out what happened to his first family after he took a second wife.

The beautiful tomb of the coloured mosaic chips – “jian nian (剪黏)” – was next. Lovingly cleaned and glued back by a brownie over the last weekend. This is the tomb of the five cats, all decorated in a myriad of scattered colours. For an example of a finely restored mosaic chips, look no further than the roof tops of the Hong San See Temples at Mohamed Sultan Road, which received, a UNESCO award for restoration.

From 5 cats, it was just two stops over to Wong Chin Yoke, who on a covert operation in Indonesia was betrayed and killed by Japanese forces during WWII. His remains returned after the war, and he was given military honours at his funeral. Guarding his grave are two life size Sikh Guards.

From there, we moved to the end of Hill 4, adjoining the big bungalows of Caldecott, and visited with two luminaries from our early past,

At the grave of Cheang Hong Lim (CHL), Fabian pointed out how the tombstone was different from the shoulders, which were deep grey and carved elaborately. That’s because CHL was reburied from his family burial grounds in Queenstown area. Once the richest man on the island, he too, had to move house. His vast fortune was amassed from the misfortunes of addition, and many were coolies who could ill afford a opium habit. Yet he was generous to a fault, any appeal for charity would not be turned down. In the end, the question was asked, was he seeking redemption?

Tan Kim Ching, the eldest son of Tan Tock Seng was the last stop. What greater contribution to the then community of the disfranchised and the poverty stricken, the gift of a pauper’s hospital. A hospital that has grown, through the continued contributions of his descendants from Tan Kim Ching his son to Kim Ching’s grandson Tan Boo Liat et al. On his tombstone, Tan is honoured as a special envoy of the King of Siam. It is through a meeting between him and George Henry Brown, that led a widowed governess into the Siamese court to teach the children of King Mongut, the inspiration for the musical “The King and I ”

The brownies have visited the descendant of Tan’s second family, a wife bestowed on him by the King no less. And at the descendants house, which is a line from the daughter of Tan, we saw the jade beads that sometimes appear on the formal portrait of Tan Kim Ching. Unlike, CHL, Tan’s titles from the Manchu Court of China was of the second order. But Tan lived in an earlier time before Cheang Hong Lim, who paid for the title of the first order.

Reflection:

As we glimpse into the lives of the very wealthy and prominent leaders of the Chinese community of that time, we look at not only how they made their money from plantations of pineapples, rubber, and property, but also how they spent it -some may have been profligate – but there were definitely the ones who used their reputation, influence and wealth, to build a better life for the poor, a better society, and a better country. We visited with two this morning.

Thank you to the 20 people who turned up, engaged with Fabian and Catherine, asked interesting questions, shared their insights, we enjoyed your company. Please visit with us and other brownies when they explore other hills. We are in our 11th year of guiding walks and we have learned much on our journey with our visitors, and so we do what we do best, we tell stories.

100,000 graves, 100,000 stories.

The escape by sea, the irony of being rescued and sent back to the “fortress” island that fell so ignominiously

by Catherine Lim

I was working on a production of History from the Hills – an 8 episode docu series which traces the history of Singapore from the perspective of Chinese pioneers who made significant contributions to society and the region in the late 1800s to the 1900s (post-war) and who are buried in Bukit Brown.

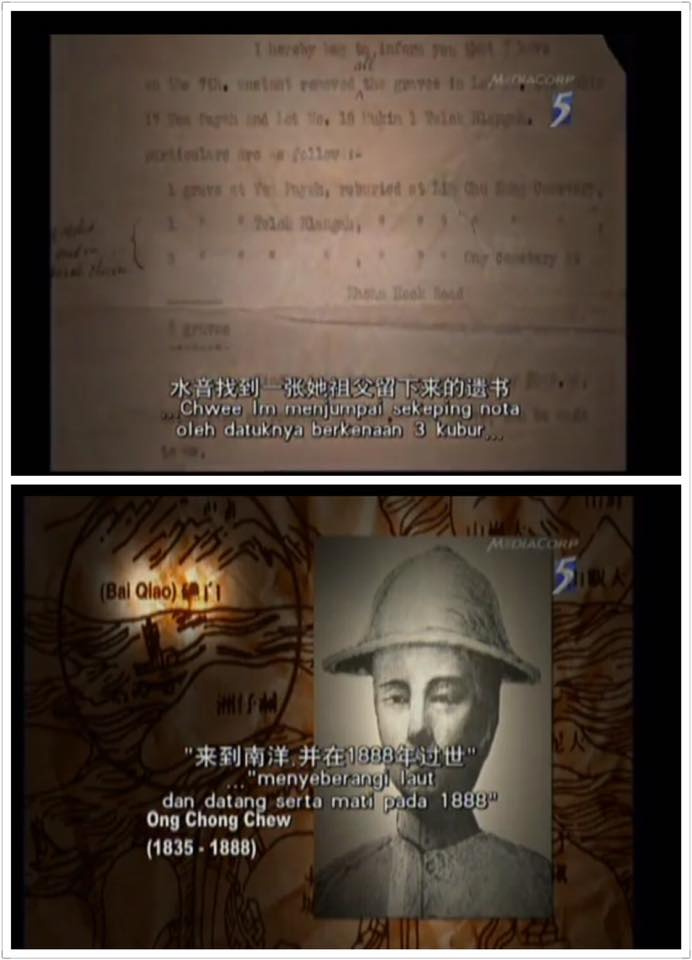

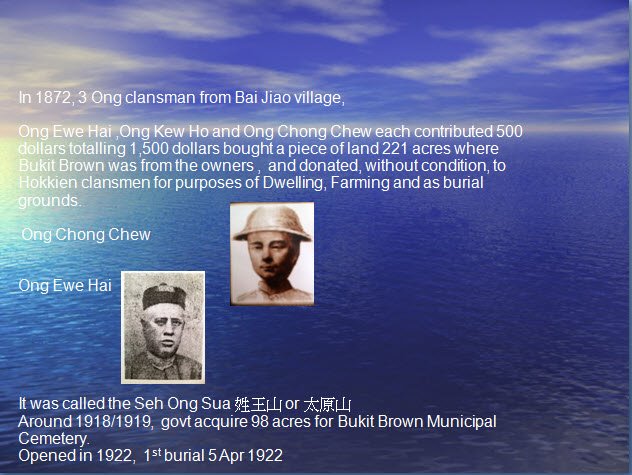

We were to shoot a sequence with Ong Chwee Imm – whose great great grandfather Ong Chong Chew was one of the three Ong “founders” of Seh Ong land – with Raymond Goh. A few weeks before, Chwee Imm had come across a document from among her father’s papers which recorded the graves of Ong Chong Chew together with 2 other family members exhumed from the Telok Blangah family burial ground, had been re-interred to Seh Ong Cemetery.

Seh Ong cemetery also sliced into two parts because of the Lornie Road expressway straddled the expressway; alongside Sime Road adjoining the Bukit Brown Cemetery side and across where the golf course is. There was no indication which side the re-interred exhumed graves may have been relocated. However because extended family including that of Ong Chong Chew’s son Ong Kee Soon’s grave was located on the golf course side, the speculation was that the re-interred remains might be located there. It was a long shot which received an extra boost, when the night before the shoot, Chwee Imm’s brother mentioned that as a child he had accompanied their mother to visit some graves before the expressway was built, and so the mood on the morning of the shoot was palpable and brimming with anticipation.

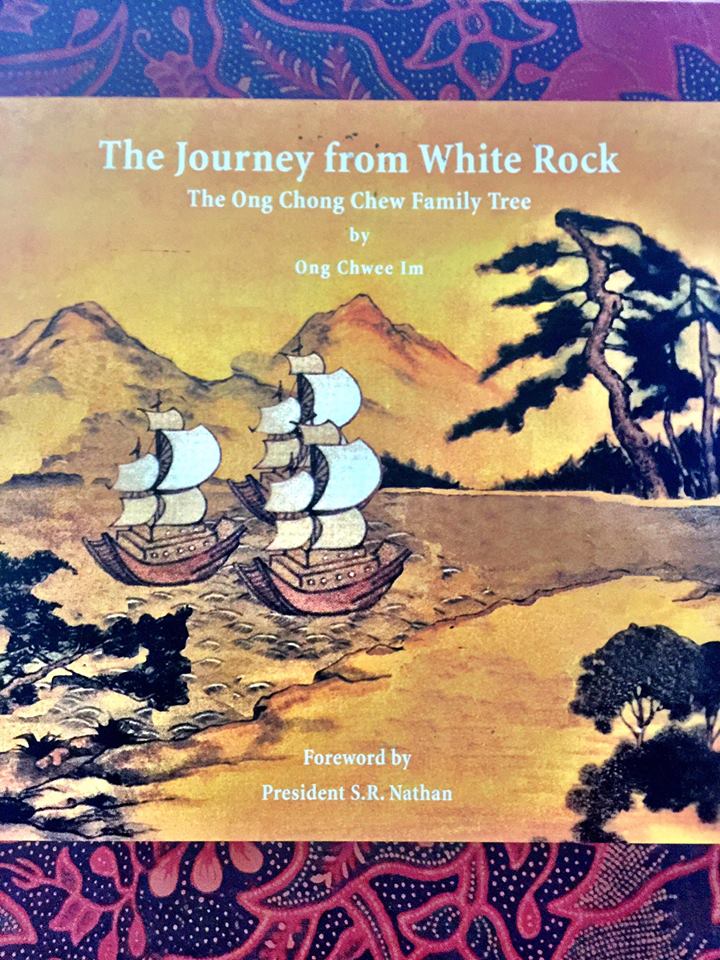

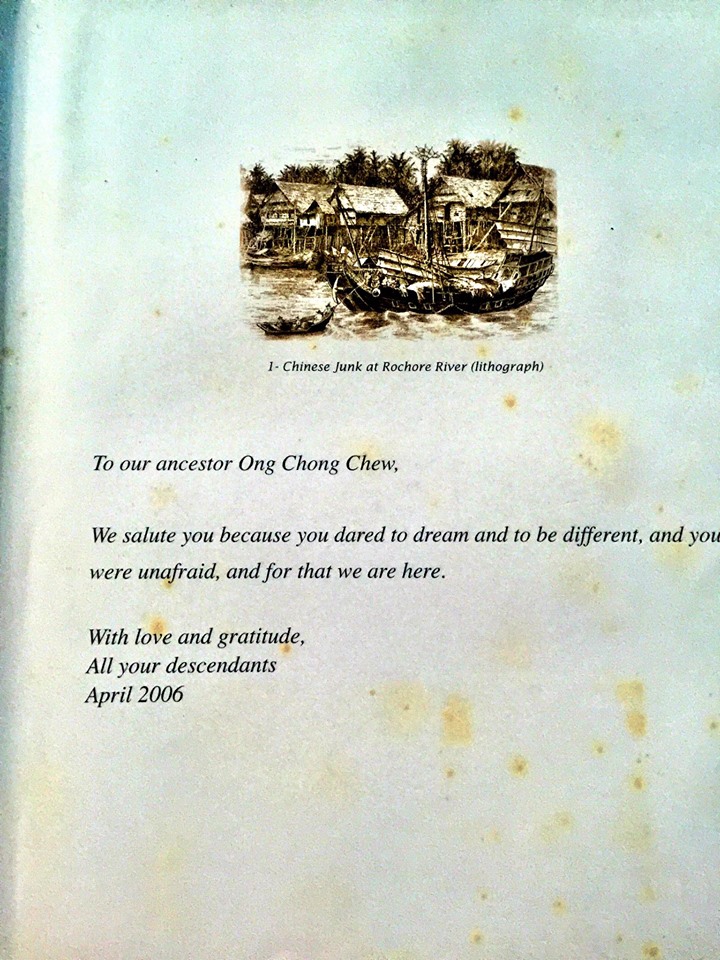

Chwee Imm had long wanted to find the grave of her illustrious ancestor ever since she had written and published ” The Journey from White Rock” (2006) tracing Ong Chong Chew’s life story and his legacy from his hometown in “White Rock” China to Singapore. It would be the final piece missing from her story.

Tomb of Ong Kee Soon, 2nd son of Ong Chong Chew and from whose line Chwee Imm is descended at Seh Ong ( photo Raymond Goh)

The search was undertaken around the area where Ong Kee Soon’s grave was located. It was “bush bashing” terrain and after an hour into shoot when Chwee Imm fell into a depression in the ground, it was decided that the search would be abandoned for safety reasons.

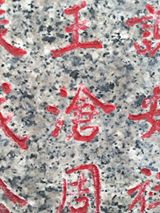

Fast forward, Saturday 17 September, 2016. Raymond Goh on his usual solitary weekend explorations and research in the vicinity of what remains of Seh Ong bordering Bukit Brown, suddenly decided to look down and this was what he saw:

Here are some notes from Raymond’s post on the FB Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown :

“Rediscovery of Ong Chong Chew, his eldest son Ong Kim Cheow and Kim Cheow’s wife in Seh Ong cemetery. Chong Chew’s tomb was a remake when he was re-interred from his family burial ground in Telok Blangah to Seh Ong. Date on tomb -1888. All his children inscribed on tomb matched the records. Kim Cheow was a founding member of Straits Chinese Recreation club and died in 1909, hence his tomb still indicated Qing era, his daughter married Tan Hay Leng, son of Tan Kim Ching”

(The original document from Chwee Imm’s papers had indicated 3 family members including Ong Chong Chew)

Ong Chong Chew also contributed to Chong Wen Ge, Heng San Teng and Sian Cho Keong 仙祖宮(Amoy St)

Raymond Goh offering prayers at a shrine in the vicinity just before he chanced upon the Ong Chong Chew cluster of 3 tombs

At the time of the rediscovery of Ong Chong Chew’s tomb, Chwee Imm was abroad and relatives on FB helped to contact her to inform her.

We look forward to hearing more from her when she has had a chance to visit. But there is no doubt, that given the dedication which was written to her august ancestor in her book, the finding of the tomb marks another important milestone in her journey to White Rock.

For those who are interested in the first episode of History from the Hills which featured the history of Seh Ong land and the initial search for Ong Chong Chew :

More on the founders of Seh Ong here

It was Samira’s first visit and she penned these reflections to share.

“I doubt there are textbooks or academic sources that would be able to do justice to the arcane yet insightful details the places in Bukit Brown had revealed about our past – and these pieces of our tangible history are truly irreplaceable.”

by Samira Hassan

Dateline: Bukit Brown (14th August 2016)

We started the trail off the sidewalk on Lornie Road near a clearing just pass the turn in to Caldecott Hill. It would have been all too easy to miss it whilst walking – overgrown creepers had landscaped the steep steps that led us down the path to the trail. The steps themselves were uneven and rickety, an omnipresent feature in Bukit Brown’s landscape.

The cemetery is sprawled over 5 hills (blocks) as high ground was thought to represent the back of a dragon, an auspicious symbol in Chinese culture.

We first made our way to the tomb of Lim Kee Tong and his wife.

Grave of Mr and Mrs Lim Kee Tong, note the grape vines on the border to the tombstone (photo Catherine Lim)

Their tombstone was largely inspired by post-modernist designs of colonial times with Chinese lions. A mound behind the tombstone is where they are buried, enclosed in a horseshoe shape defined by a brick border. Each feature on the tombstone it seems had its own specific meaning; for example, the vines of grapes at the border of the headstones, because of its seeds, signified the wish for many more generations to follow.

The horseshoe shape is also reminiscent of a womb, alluding to the circle of life. The design of the grave incorporates a drainage system which would direct rain water to flow to the bottom, an important component in fengshui. Water is “chi” or energy and also represents wealth. Diverting water away from the mound helps to stay the course of decomposition, although it is inevitable.

Inscriptions on the tombstones included names of the deceased, dates of death and place of origin. It was explained that sometimes posthumous auspicious names were given as mark of respect by the children. Names of children are also included in the inscriptions so it seems like each grave is family monument in itself. Features and inscriptions on each grave can reveal some aspect about the person’s life and hopes for the family.

And in Bukit Brown, every grave has a story to tell – even the grave of paupers. Moving into the pauper area of Bukit Brown, we learned of the rickshaw puller Low Nong Nong who died in clashes with police when rickshaw pullers went on strike and demonstrated against the increment of rickshaw rentals.

The other rickshaw coolies then pooled together enough money to buy Nong Nong a tombstone and a funeral to acknowledge his sacrifice. In the midst of the other *pauper tombstones where there was barely enough money to erect a simple headstone, Nong Nong’s tombstone was comparable in size to the tombs in the paid plots and also because the mound itself had been cemented over, perhaps because his comrades realised that since he died without kith and kin, there would be no one to help maintain his grave should they themselves pass on or manage to make enough money to return home to China

*Under the colonial administration, free plots in Bukit Brown were set aside for those who died destitute

The fact that even paupers like this rickshaw puller had a story, had a voice, was something that I really appreciated in Bukit Brown: there was no particular class, or group of people, that were entitled to the plot of land, that all of these seemingly disparate narratives had managed to tell a bigger story of Singapore’s history. Such heterogeneity transcended into Ong Sam Leong’s tomb as well, the biggest one in Bukit Brown.

Group photo of ramblers at Ong Sam Leong’s grave, Samira is in the middle in green tshirt, carrying blue and pink tote bags (photo Peter Pak)

The most fascinating thing about his grave were the statues of the Punjabi guards stationed at each side. Around Malaya at that point in time, the British had recruited Punjabi soldiers and policemen from India. Given their positions of authority, they were almost seen as the “guardians of the state” They became also personal body guards of rich towkays such as Ong Sam Leong at a time where lawlessness was more prevalent. For me it demonstrated a deep level of trust between diverse communities and reflected a nascent multicultural society Singapore in the 1900s.

Sikh guards protecting a Chinese reformist fugitive from the Qing Dynasty, Kang You Wei when he sought refuge in Singapore. (Photo from Lai Chee Kien)

Bukit Brown has grown to be more than a resting place for the deceased – it has become a physical emblem of a society that was present in early 20th-century Singapore. From the most minute details in the tombs to the way the entire cemetery is organized – all of these provide important snippets to what civil society used to be like back then, I think this really goes to show that there is sometimes no alternative for trails and fieldwork such as this one.

I doubt there are textbooks or academic sources that would be able to do justice to the arcane yet insightful details the places in Bukit Brown had revealed about our past – and these pieces of our tangible history are truly irreplaceable.

=================

Samira is a year 5 student with Raffles Institution, who is currently serving an internship with Singapore Heritage Society to better understand the challenges of conservation and heritage development

Information on public guided walks when and where and how to register can be found by following Bukit Brown Events on Peatix

The tomb of Wee Theam Tew is yet another significant discovery made by tomb whisperer, Raymond Goh in the Greater Bukit Brown. Wee Theam Tew was a lawyer and died at the age of 52 due to his failing health. His tomb has inscriptions in both English and Chinese, and a set of poetic couplets, which is believed to enhance the livelihood of the deceased’s family. This one reads:

坐山脈正派

向水源當長

添秀山為景

籌華地作玩

This is how one member of the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook community, James Koh translated the couplets to English and added his interpretation of the significance of the words :

The mountain sits with honorable aura

The river flows with abundance

The hills add charm to the landscape

The earth becomes pleasing to the eye with accumulated lustre

He adds that the couplets “represent the things which Mr. Wee wish to bestow on his descendants — reputable status, decent lineage and legacy, strong prospects, and a happy home.

What makes these couplets interesting is, in each sentence, there is supposed to be a stop after the first two words. For e.g., 坐山 ¶ 脈正派. But the second and third words actually form a noun which is related to Mother Nature — 山脈, 水源, 秀山, 華地. This, in turn, displays Mr. Wee’s brilliance in Chinese literature.”

We are assuming these were either written by Wee or chosen by Wee.

Do join the discussions in the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook group page, a platform for all members like James Koh, to learn, as well as contribute and share their knowledge in all things related to heritage, habitat and history.

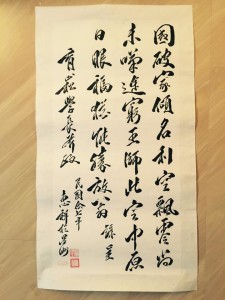

When the country is broken and families are upturned, fame and fortune mean nothing.

Although I am forced to wander, I am not yet lamenting that our cause is hopeless.

My eyes may be luckier than that of Lu You, for I may (live to) see the day when the righteous army sweeps north and pacifies the central plains

[i.e., when we have driven out the Japanese].

Mdm Chng of the Pang Family – A Mother of Journalists, Educationists and Revolutionaries

by Ang Yik Han

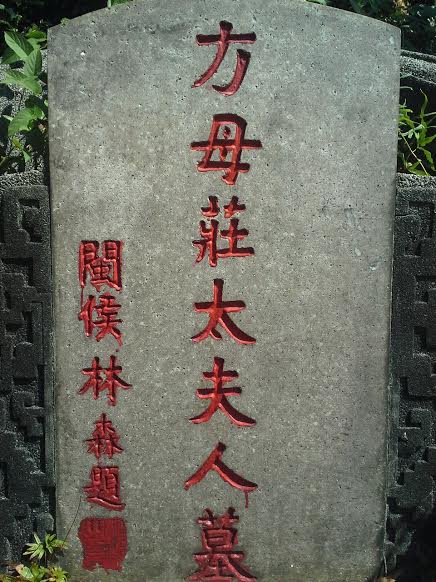

The tombstone of Mdm Chng, who died in 1936 at the age of 77. The characters on the tombstone were written by Lin Sen, KMT Chairman. (photo Yik Han)

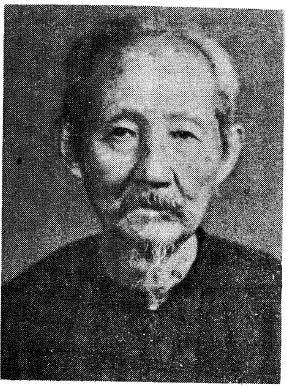

Located at Hill 4 in Bukit Brown, the Teochew style tomb of Mdm Chng of the Pang family (方母莊太夫人) is simple and nondescript. A sharp-eyed observer will notice however that the calligraphy on the tombstone came from the hand of Lin Sen (林森), Chairman, of the ruling pre war Nationalist government in China.

Another sign of her family’s close connection to the Kuomintang was the fact in her obituary in the Nanyang Siang Pau, she was described as the mother of a martyr. This was in reference to her second son, Pang Nam Gang (方南岡), whose story was recorded in Feng Ziyou’s “Anecdotal History of the Revolution《革命逸史》” published in 1948.

Although two of Mdm Chng’s sons passed away before her, the names of all her sons were inscribed on her grave: Siao Cheok少石 (deceased), Nam Gang 南岡 (matyred), Chee Dong 之 棟, Huai Nam 懷南, Chee Cheng 之楨. Also present were the names of two daughters, though her obituary only mentioned one surviving daughter.

Pang Nam Gang had a good grounding in classical Chinese education. However, he spurned the traditional path of becoming a mandarin and chose to pursue his studies in Japan. There, he joined the Tongmenghui. Deeply committed to overthrowing Manchu rule, he devoted his time outside of studies to learning how to make bombs.

In 1905, Pang and eleven of his compatriots in Japan were ordered by Sun Yat-Sen to return to China to assist in the Huang Gang uprising in the Teochew region. Injured while preparing bombs, he was brought to Hong Kong and hospitalised, hence missed out on the action. When the uprising petered out, Pang decided to join his uncle who was a local governor in Gansu, with the intention of seeking opportunities to incite the local Hui people to rise against the Qing. His uncle was initially pleased to see his nephew, but flew into a rage when word reached him that Pang was a revolutionary. Locked up by his uncle, Pang escaped with the help of other relatives, stealing two horses and riding to Hankou, where he sold the horses and boarded ship for Japan to continue his studies. Eventually, he made his way to Penang where he became the editor of the Kwang Wah Yit Poh newspaper which was linked to the Tongmenghui.

The young revolutionary could not sit still for long. When news of the successful 1911 uprising in Wuhan reached the Nanyang, Pang rushed back to China where he raised a fighting force in his home county of Pho Leng. When Yuan Shikai was elected the first President of the nascent Chinese Republic, Pang felt that Yuan could not be trusted as he had too many links with the old regime. Disgruntled, he returned to Penang where he took up his old job at the newspaper.

Pang’s worst fears came true in 1915 when Yuan Shikai assumed the title of Emperor. This time, he could no longer abide the situation and returned to China again to fan the flames of revolution. Unfortunately, he was captured in Macau by Yuan Shikai’s agents and smuggled across the border and imprisoned. At first, he assumed a false identity and did not divulge any information even under torture. However, his fervent preaching of revolutionary ideas to his fellow prisoners gave him away and he was summarily executed. So perished a martyr of the Chinese Revolution at the age of 29.

Photo of Pang Nam Gang (reproduced from the book “The Teochews in Penang: A Concise History” by Mr Tan Kim Hong)

The house of Pang Nam Gang in Pho Leng (taken from the site 方益森的博客 http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_756c1ab90101ipv2.html)

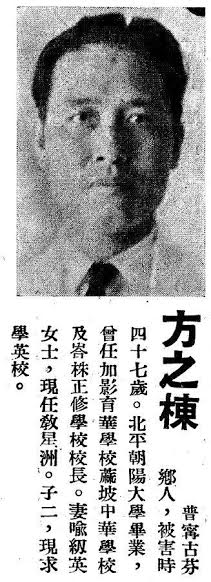

Mdm Chng’s obituary also mentioned that her three surviving sons were active in the areas of journalism, education and social works. Her youngest son, Pang Chee Cheng (方之楨), was in the limelight as well for his involvement in politics. A journalist, he was a KMT cadre who actively canvassed support for the party as one of the main committee members of the Nanyang branch headquarters.

In 1930, Sir Cecil Clementi became the Governor of the Straits Settlements. He had a dislike of the KMT due to its instigations of strikes during his previous posting in Hong Kong. On the day that he arrived and assumed office in Singapore, it was unfortunate that the KMT Nanyang branch headquarters chose to hold its general meeting at the same time.

One of the first acts of the Governor was to summon the KMT representatives to his office where he told them in no uncertain terms that the KMT was not allowed to operate local branches in the Straits Settlements and Malaya. A few months later, the Governor upped the ante by issuing orders to deport Pang Chee Cheng and another KMT stalwart; well aware of the situation, they left on their own for China first.

Quiet diplomacy between the British and Chinese governments behind the scenes eventually led to the deportation orders being rescinded. In later years, Pang Chee Cheng was based largely in China where he was active in the Overseas Community Affairs Council (僑務委員會) set up by the Nationalist government.

Pang Chee Cheng often met with renowned personalities of the day. So it was that when the Indian poet Tagore visited in 1927, Chee Cheng arranged for him to travel to Muar and visit Zhonghua School (中華學校, a forerunner to today’s 中化), where Tagore was received by his brother Pang Chee Dong (方之棟) who was the principal then. A graduate of a university in Beijing, Chee Dong was successively principals of Chinese medium schools in Kajang, Muar and Batu Pahat. In 1933, he may have worked as editor of a Chinese newspaper in Rangoon as well.

After the Japanese invaded, he perished during Sook Ching in Singapore, leaving behind his widow and 2 sons.

A short biography of Pang Chee Dong in the 8th anniversary commemorative publication of the Nanyang Pho Leng Hui Kuan published in 1948.

The fourth son Pang Huai Nam (方懷南) was the first editor of Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商報) established by Tan Kah Kee in 1923. Slightly less than a month into its publication, he left the newspaper as the Straits Settlements authorities found his writing too political for their liking. He was also a committee member of the Poit Ip Huay Kuan and principal of Choon Guan School. It was mentioned in Phua Chay Leong’s “The Teochews in Malaya” that he shared the same sad fate as his elder brother Chee Dong during Sook Ching.

Mentioned as well in Mdm Chng’s obituary was one of her grandsons, Pang Say Hua (方思法). Born in Singapore to her eldest son, he was “fostered” to his uncle Pang Nam Gang; his father was convinced that his second brother would come to no good end with his revolutionary ways and hence it was better that he had a son to his name. Pang Say Hua went back to China to study and subsequently became a signaler in the Nationalist Army. He was one of the many caught up in the tumult of the times. Due to his background, he suffered after the Communists took over, being imprisoned for over ten years. After his release, he worked at various jobs and retired in 1980. His story became known when a civic organisation in the Teochew region which sought to recognize veterans of the Sino-Japanese War found him and publicised his story.

Single for life, he attended church regularly and spent his last days in a Christian old folks’ home where his favourite pastime was to watch Teochew opera. He died in Jan 2015, a month after he celebrated his 104th birthday.

Source: http://www.stcd.com.cn/html/2013-09/21/content_464908.htm

He was an old trustee of the Soon Thian Keing (Temple) who together with his wife is buried at Bukit Brown. Through his personal memories, Ho Siew Tien (1864-1960) helped shed light on the temple’s history.

This story by Ang Yik Han begins with the origins of one of the oldest temples in Singapore.

***************************************************************************************

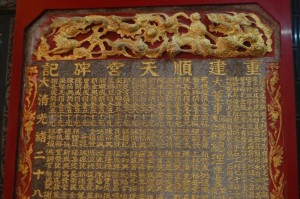

In the 1980s, a debate took place in the local newspapers over the age of an old Chinese temple dedicated to the earth deity Tua Pek Kong in Malabar Street. Historians argued over an ambiguous phrase in one of the temple’s old stelae, which stated that the temple, the Soon Thian Keing (順天宮), was established during the years of the reigns of Jiaqing and Daoguang (“嘉道之際”). As the Jiaqing Emperor ruled from 1796 to 1820 and Daoguang from 1821 to 1850, proponents of an earlier dating for the temple argued that its establishment may have predated the founding of Singapore in 1819. However, there was no direct evidence to support this claim. No artefacts survived from the temple’s earliest days and the stele in question was erected only in 1902 when the temple was reconstructed.

Part of the 1902 stele still preserved in the Soon Thian Keing today. It shows the main temple sponsors and major contributors to the temple’s building fund (photo Yik Han)

One the earliest known accounts of the Soon Thian Keing before its reconstruction was an interview given by one of its trustees, Ho Siew Tian (何秀填), in 1949. He recalled that when he first arrived in Singapore in 1882 at the age of 18, the temple was only a small shrine located next to a tree which housed the Tua Pek Kong statue. The shrine was refurbished by two merchants in 1888. It was only in 1902 (28th year of Guangxu’s reign) that some merchants based in the Sio Po area (the colloquial Chinese term for the part of town north of the Singapore River) came together to construct a proper building for the temple.

Other than getting a new building, the turn of the 20th century was significant for the temple for another reason. Some Hokkien merchants started a school in 1903 and then turned to the temple committee for funding to sustain the school. Thus began the decades long association between the temple and the Chung Cheng School (崇正学校) [not to be confused with Chung Cheng High (中正學校) which was managed by the Hokkien Association].

Every year, the temple provided for the school’s upkeep from the money paid by the resident monk who was contracted to run the temple. In 1916, a school for girls, the Chong Pun Girls School (崇本女校) was started and likewise funded by the temple. Committee members of the Soon Thian Keing sat on the boards of both schools. Prominent alumni members of the Chung Cheng School over the years included Lee Kong Chian and President Ong Teng Cheong.

As the number of students increased, the need for new premises for both schools was keenly felt. In 1938, the construction of a new school building at Aliwal Street was completed. This housed both the Chung Cheng School as well as the Chong Pun Girls School under one roof. It was recorded that Ho Siew Tian was a prime driver in the construction of the new school building along with the then temple chairman. A trustee of the Soon Thian Keing since 1933, he was concurrently the treasurer of the temple and the two schools, a position he held till after the war.

Hailed as one of the most modern Chinese school buildings of its day, the building has been preserved and is today the Aliwal Arts Centre.

As Aw Boon Haw donated substantial funds towards the building’s construction, the school hall was named after his company, Haw Par.

Old photos dating from 1950 which showed girls of Chong Pun exercising in the school field, today a carpark. Sultan Mosque can be seen in the background.

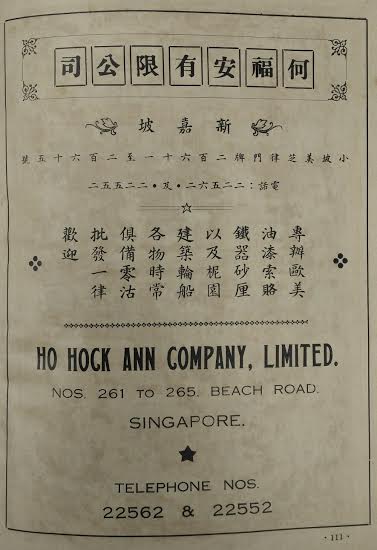

Ho Siew Tian ran a thriving hardware and building materials business under the chop Ho Hock Ann (何福安) at Beach Road. He also owned a number of twakows for transporting goods. As his wealth grew, he made substantial investments in properties. In 1948, he incorporated his firm as a limited company and handed over its running to his sons, who subsequently expanded the business to firearms.

It was urban redevelopment which spelled the end for the temple and the schools. In 1980s, the temple was acquired by the government for building the MRT. It moved successively to various temporary sites before its present building at Lorong 29 Geylang was completed. With the resettlement of the urban residents in the area, dwindling student enrolment led to the closure of Chung Cheng School in the 1980s as well. Its name was transferred to a primary school in Tampines.

Soon Thian Keing today in Lor 29 Geylang (photo Yik Han)

Ho Siew Tian is buried at Hill 4 together with his wife who died 12 years before him. According to obituaries in the Straits Times and the Singapore Free Press, he was one of the oldest men in Singapore at the point of his death at the age of 96. He was survived by 5 sons (2 other sons died before him), 3 daughters, 2 sons-in-law, 7 daughters-in-law, 81 grandchildren, 8 grand sons-in-law, 4 granddaughters-in-law and 37 great grandchildren.

Ang Kok Kian – A Pioneer of the Soap industry

by Ang Yik Han

It is not clear if Ang Kok Kian (洪轂堅) grew up in Penang or he travelled there from his ancestral village in Nan’an county, Fujian province. During the 1910s, he moved to Taiping with his family but left after two years for Singapore, where he felt there were better prospects.

Of the businesses he established in Singapore, the most successful was the See Sen Soap Factory (時鮮肥皂廠), one of the local firms which rose to challenge the dominance of the market by Western manufacturers then. Although sales trailed behind another local firm Ho Hong Soap Factory, its distinctive “Dog’s Head” (狗頭標) brand soap was popular in Singapore, Malaya, Borneo and Hong Kong, both before and after the war.

Dog Brand Trade Mark (Source https://moulmeincacc.wordpress.com/2014/06/03/castle-at-no-19-barker-road/)

Ang Kok Kian passed away in 1939, leaving behind 4 sons. By then, his eldest son Ang Hai Sun (洪海山) was actively involved in the family business. Not content with expanding the soap factory, he went into oil milling to ensure a stable supply of raw materials for the factory.

Although “Dog’s Head” soap has disappeared from the market for decades, the mark of this locally produced soap can still be seen today adorning the house which Ang Hai Sun built, where his descendants still reside.

Home of the present descendants of Ang Kok Kian (source https://moulmeincacc.wordpress.com/2014/06/03/castle-at-no-19-barker-road/)

More information on his descendants here

Double tomb of Ang Kok Kian and his wife at Bukit Brown Hill 4

Died in the year of the Horse, 19 July 1942 and survived by one son named Kah Bo (嘉謀), Hou Xiu Xi ( 侯秀西 )located at Hill 1 was said to be a good orator and a staunch supporter of the China Relief Fund led by Tan Kah Kee.

He spoke at public rallies and occasions such as temple celebrations to exhort the local Chinese to support the anti-Japanese cause. According to an account, he was beaten to death during the Japanese Occupation for refusing to cooperate with the Japanese authorities.

Recent Comments