Located by the roundabout in Hill 1 (near the LTA signboard) is the tomb of Thio (Teo) Guan Tat who came from Fujian Province and was a pioneer in the remittance business.

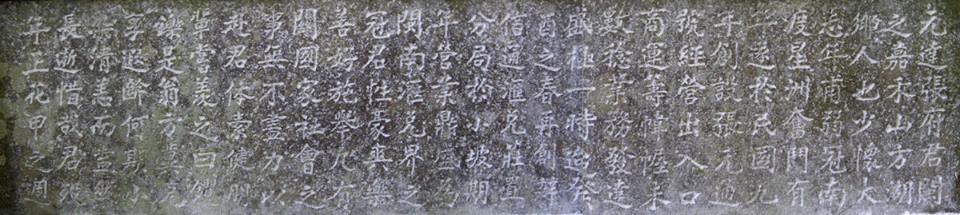

On the altar of his tomb, is an epitaph inscribed in elegant calligraphy

Summarised by Brownie Khoo Ee Hoon:

“Mr Thio Guan Tat came to Singapore as a youth with high aspirations and who strived for many years before succeeding. Finally in 1920 he started “Thio Guan Tong” a import and export business. He profited from his business and shortly after started a remittance agency at South Bridge Road. His remittance business became the most well known and popular Hokkien Remittance company.

Mr Thio is a generous and kind man, who lend a hand to his fellow clan men and society.”

Thio’s tomb stake number 1044 will have to be exhumed to make way for the highway

Mian-Yu-Ting Cemetery, Johor (Part II)

by Choo Ai Loon

(Ai Loon continues from part one of her blog post on Mian-Yu-Ting Cemetery )

Among the tombstones at the Mian-Yu-Ting , is one belonging to Wu You-Xun (邬有询), which pays tribute to his alma mater, Chinese High School (華僑中學 in traditional Chinese characters)

A student with a promising future, Wu You-Xun (邬有询) aspired to become a doctor, In 1920, after completing his Senior Cambridge examination (equivalent to GCE “O” levels) , he enrolled at Chinese High. He graduated among the first batch of students, two years later. In the graduation year book, he was described as a hardworking student who “had no time to chit-chat as time was too precious”.

Wu excelled in English and was a committee member of an English speech society, which I presume was the “Nanyang version of the Toastmasters Club”, and chief editor of an English magazine.

But alas! Wu passed away at just 22 years old, a year after graduation. Inscribed on his tombstone is “graduate of Chinese High School” is a reflection of how proud he must been of his school

In contrast, one grave has only 3 characters inscribed but no name. Gu-ren-mu (古人墓), literally means “the tomb of someone who has passed away”.

This typical Teochew tomb which resembles an arm chair, a pair of couplets in red on the scroll pillars.

The arms of the tomb curve gracefully and there is a dragonhead carved on it The usual practice of depicting the whole dragon it seems has been adapted to just a dragon’s head. I have observed these variations in motifs and representations. This dragon appeared benign compared to the fierce-looking ones found in older tomb carvings.

Another grave had steps leading up the tombstone perhaps imitating a stupa, influenced by Buddhism.

The Tomb of She Mian-Wang

She Mian-Wang (佘勉旺), belonged to a wealthy Teochew family. The surname “She” is more commonly spelt as Sia or Seah.

The She Mian-Wang family profile in Johor parallels that of the Seah Eu Chin in Singapore. Both families had made their fortune from the cultivation and trade of gambier.

Seah Eu Chin’s tomb was discovered in 2012 within Greater Bukit Brown, in a forested area called Grave Hill in Toa Payoh West, Singapore. He co-founded and led the Ngee Ann Kongsi in Singapore, to look after the religious needs and welfare of early Teochew migrant workers.

Similarly, She Mian-Wang was an important figure in the Ngee Heng Kongsi The enormous plot size and the expansive tomb arms of She’s grave reflects his status and wealth in those days. Interestingly, his tablet is enshrined and worshipped at Pu Zhao Chan Si Temple (普照禅寺) in Singapore.

So could these two powerful families in the Teochew community be related? I leave you with this parting thought .

My thanks once again to Mr Bak Jia How and Mr Pek Wee-Chuen for the insightful and enjoyable tour of Mian-Yu-Ting.

Thanks to Mr Bak Jia How and Mr Pek Wee-Chuen for the insightful and enjoyable tour.

Choo Ai Loon, works as a translator and is passionate about art and heritage, She supports Hair for Hope for children with cancer. She blogs at http://chooailoon.wordpress.com/2013/05/05/hair-for-hope-2013/

On a bright Sunday morning, a descendant of the family of Tan Kheam Hock spent 4 hours clearing one of his families’ clusters. Edmon Neoh-Khoo was assisted by Brownie Khoo Ee Hoon who both helped in the clearing and documented the effort. Edmon is also an avid gardener and will continue to look after the tombs of his extended family in Bukit Brown. We salute Edmon for fulfilling his filial duties in such an exemplary manner.

In Hill 2, clearing the way to the family cluster of Tan Kheam Hock.

The tomb of Daisy Tan, granddaughter of TKH, She passed away at 2 months old, dob Oct 28- dod Dec 26. 1933 (photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

A tools of filial piety at the tomb of Tan Poey Joo, granddaughter of TK, dob Sept 22, 1933 – dod May 26, 1954(photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

A special visit to Tan Poey Choo, granddaughter of TKH, to fulfill a brownie promise (photo Khoo Ee Hoon

There is an old Chinese saying:

“Remember the Source of the Water”

We would like to say a big THANK YOU to the My Singapore Destination meet up group for their contributions to clear tombs at Bukit Brown.

Because of your help, a tree which had fallen over the tomb of pioneer Cheang Hong Lim has been removed with the help of tomb keeper Soh Ah Beng.

The clearing of the tomb also paved the way for access to the tomb behind, belonging to Tan Kim Ching.

Clearing was made tougher because of a beehive on the tree.

by Jason Kuo ( 郭子澄)

A unique feature of some of the graves in Bukit Brown is the inclusion of the “Emperors’ Regnal Years or Eras” inscribed on the tombstones. Just as the British refer to the Victorian or Edwardian eras and America, the antebellum years, the regnal years speak to the milieu of the times under each emperor’s rule.

The regnal years are also sometimes combined with the Chinese zodiac year (天干地支), which is a 60- year cycle with each year represented by one of 12 animals (十二生肖), and each animal appearing five times in the cycle to form 60 years.

The inscription on this tomb in the Greater Bukit Brown area is of the 34th year of the Emperor Guangxu (光绪)and the zodiac year of the monkey. Guangxu’s first year of rule began in 1875, so his 34th year would be 1908 of the Gregorian year which was the year of the monkey. The deceased died in 1908, also the year Guangxu died.

With the exception of a long-reigning emperor, such as Qianlong (乾隆), any zodiac year most likely falls only once during each emperor’s reign in the last 150 years of the Qing Dynasty (清朝). For example, the year jiawu (甲午) – the year of the horse – only fell once during the reign of Guangxu. Thus the Jiawu of the Guangxu reign (“光緒甲午年”) is roughly 1894 of the Western era. This was the year of the First Sino-Japanese War, when Taiwan was ceded to Japan.

Four years later in 1898, Emperor Guangxu launched his abortive reform programme. Known as the 100-days reform (百日维新), its failure led to the execution of martyrs, the house arrest of the emperor (and continued rule by the Empress Dowager Cixi 西太后慈禧), and increasing radicalization of Chinese intellectuals. Emperor Gyangxu’s reign, was marked by defeat at the hands of the Japanese, and failure to push through reforms aimed at improving the lives of the Chinese.

Xinhai (辛亥)– the year of the pig – in 1911 was the year of the Wuchang Uprising (武昌起义) that eventually toppled the Qing dynasty. With the demise of the Qing dynasty, the “reign” title becomes Minguo 民国(民國), the republic.

This tomb shows the Mingguo year 32 on the left shoulder. Add on 11 and the year of death is 1943 in the Gregorian calendar, when Singapore was under Japanese occupation. The tomb is also inscribed with the Japanese Imperial calendar year of 2603 on the right shoulder. The Imperial year 1 (Kōki 1, 皇纪) was the year when the legendary Emperor Jimmu (神武天皇) founded Japan in 660 BC, according to the Gregorian calendar. By subtracting 660 from the Japanese imperial calendar year of 2603, we arrive at the equivalent Gregorian year of 1943.The tomb belongs to Dolly Tan whose name is inscribed in Japanese as : “Do-Ri-Tan,” to the the right of the Chinese name.

Taiwan still uses the Minguo “reign” year calendar, alongside the Gregorian calendar. This year, 2013, is Minguo 102.

About Jason Kuo (郭子澄): Born in Taiwan to mainland Chinese parents, Jason came to Singapore when he was six. Educated in Nanyang and Chinese High, he was drawn to Chinese history in particular, because as a child of of refugees, he wanted to understand his roots. He says growing up in Singapore was a wonderful experience as he was exposed to a great variety of languages and cultures. Jason, now works and lives in Hong Kong.

Further observations by the writer on the inscriptions on Dolly Tan’s tomb:

The modern Japanese dating system is identical to the Chinese imperial system. Each emperor’s reign is marked by a reign title. The current emperor’s reign title is Heisei 平成, beginning in 1989. The prior emperor ascended the throne in 1925, and was one of the longest serving monarchs in history. The Showa 昭和 reign began in 1925, and covered the years when Singapore was brutally ruled as Shonan-To 昭南島 [i.e., the southern island of Showa]. As the old emperor entered his 60th year of reign, the Japanese government was still putting out budget proposals that extended to Showa 100 or beyond, since an emperor’s mortality should never be questioned. I’m also intrigued that the tomb uses the lunar dating system even though the year is already Minguo [Minguo 32. 5th day of 4th moon], but in the Japanese rendition it kept the Gregorian system [Imperial year 2603, June 28]

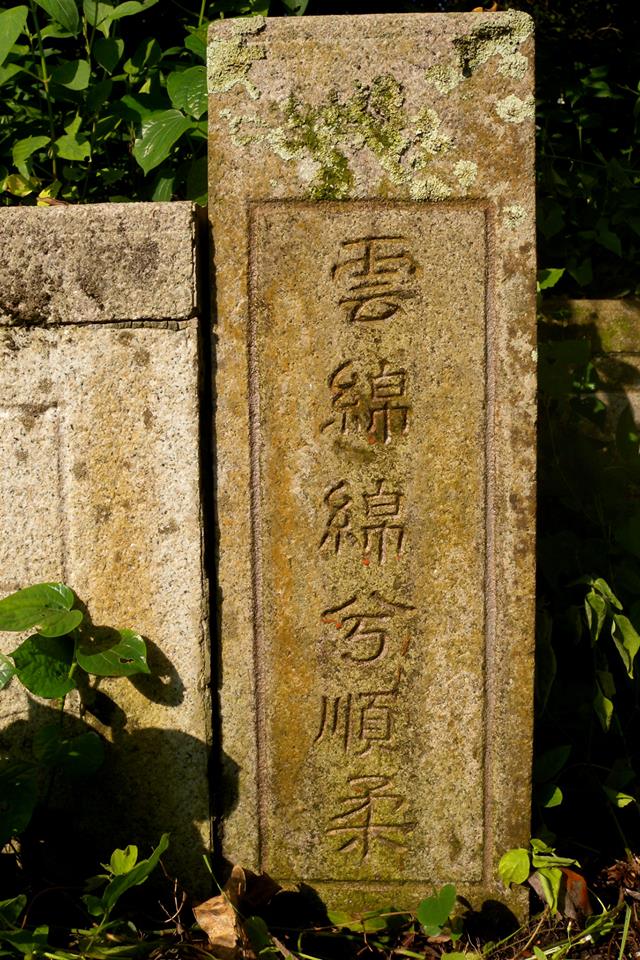

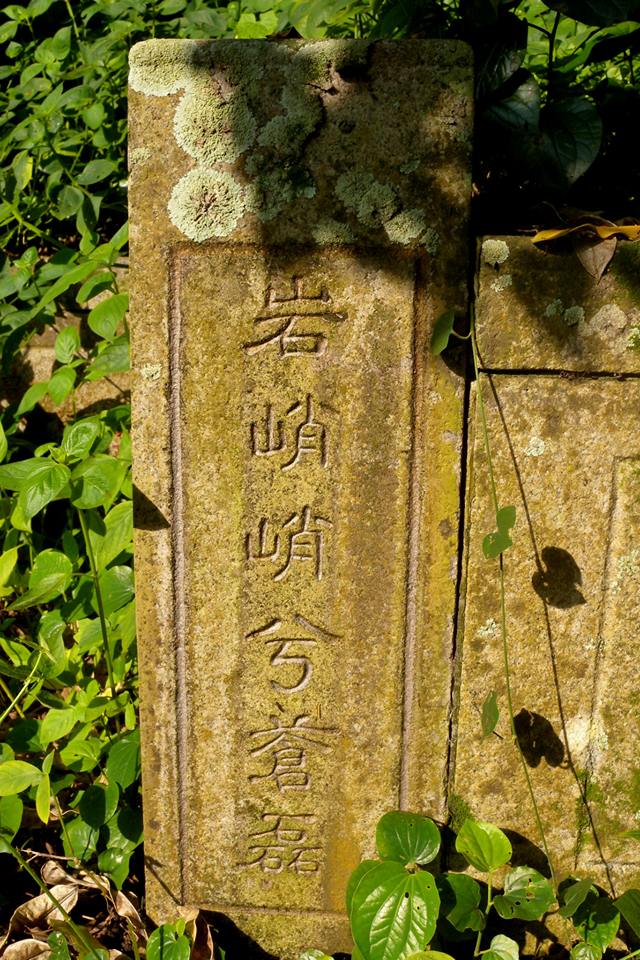

At Bukit Brown, one often finds couplets on the “pillars” of the tombs. They embed auspicious meanings and also tributes to the departed. The above couplets reads:

雲绵绵兮柔顺

岩峭峭兮蒼磊

Translated by Tay Hung Yong from the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery FB group, t reads

“Soft and gentle are the endless clouds;

The rock stands solid for eternity.”

Hung Yong says, “It signifies ever lasting love for the decease.”

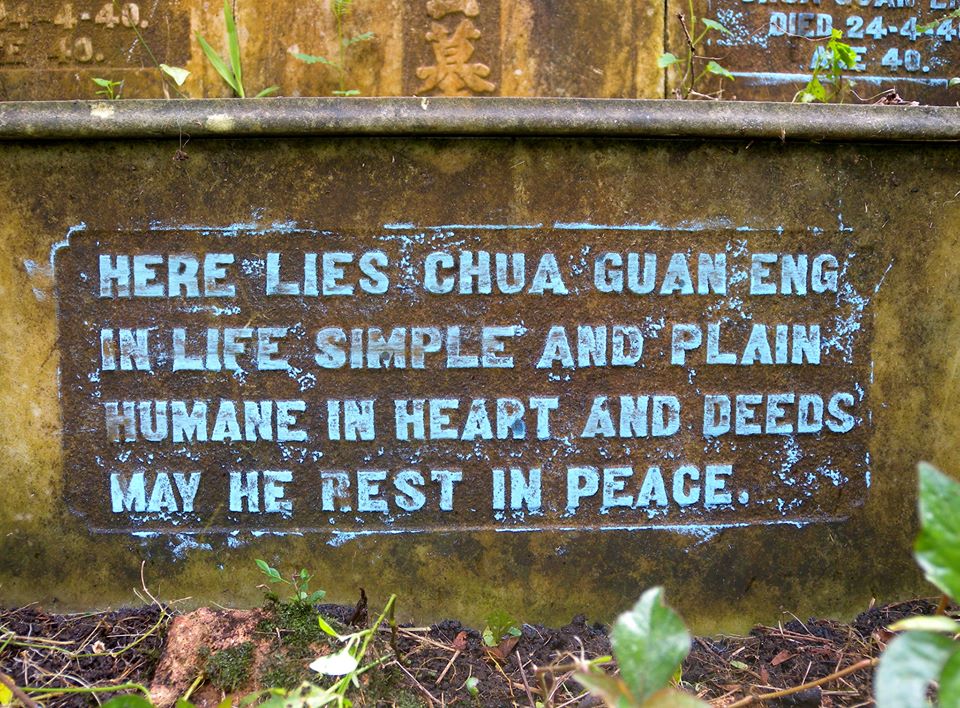

We know there once lived a man named Chua Guan Eng, who died on the 24th April, 1940 aged 40. And that is all we would have known if not for the loving tribute of the inscription on his tomb.

And today, we know Chua Guan Eng’s tomb is staked (912) and will have to make way for the highway.

The Wayang in the Tombs (2)

by Ang Yik Han

The Wayang in the Tombs 1 continues, as Yik Han unravels more iconic scenes from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and other popular stories.

“Temple of Sweet Dew” (Gan Lu Si – 甘露寺)

Zhou Yu, Sun Quan’s viceroy, wanted to lure Liu Bei over to the kingdom of Wu and then incarcerate him, on the pretext of marrying Sun Quan’s younger sister to him. Liu Bei’s advisor, Zhuge Liang, saw through this and ordered Zhao Yun, one of Liu Bei’s generals, to accompany him for protection. At the same time, he sent word to Sun Quan’s father-in-law to get Sun Quan’s mother along so that she can view her prospective son-in-law at the Temple of Sweet Dew. With the old lady around, Zhou Yu’s mischief came to naught and Liu Bei and his lady successfully got hitched.

Bowing man on left is Liu Bei, seated lady in the centre is Sun Quan’s mother, man on the right is probably Sun Quan’s father-in-law.

Editors note: An insight on how Yik Han deciphered this panel.

“The costumes especially the head dress are clues. If you look at what the man on the left is wearing, you can tell he is not just another official. For some tine I thought the figure in the middle is a male till I looked more closely at her headdress which is what you will expect a more senior lady of high social status to wear. Put these two together and you have a high ranking older male, probably some lord, paying respects to an old woman also of high social status. All the other identified panels from this tomb are based on the Three Kingdoms, and there is one famous part of the novel which has this setting, so that’s how I identified the scene. If you area Chinese opera fan, you may also recognise it easily.”

Here’s an animated excerpt from the opera

Lui Bei’s Farewell to Xu Shu

Compared to his warlord contemporaries, Liu Bei was handicapped by the lack of an able advisor. Fortunately for him, a brilliant strategist named Xu Shu joined him and helped him achieve some small victories. Just when things seemed to be going well for Liu Bei, his rival Cao Cao found out about this and he managed to get someone to send a forged letter to Xu Shu, purportedly from Xu Shu’s mother. The letter claimed she was in Cao Cao’s custody and her life was in danger unless Xu Shu abandon Liu Bei and join Cao Cao’s camp. The filial Xu Shu had no choice but to obey and the inevitable farewell came. On the day Xu Shu left, Liu Bei saw him off with his retainers and followed behind him for part of his journey. Upon reaching a forest, Liu Bei exclaimed “I want this forest to be cut down!” When his retainers asked him why, Liu Bei replied that this was because the trees blocked his view of the departing Xu Shu.

Here’s an opera you can view on the sending off.

The panels are from the tombs of the Teo Family located in Hill 2

The Third Madam teaches her son (三娘教子)

During the Ming Dynasty, there was a businessman by the name of Xue Guang who had a wife Mdm Zhang and two concubines, Mdm Liu (who bore him his only son Xue Yi) and Mdm Wang. Xue Guang conducted his business far from home. One day, he asked a man from his hometown to deliver five hundred taels of silver to his family. Instead of doing so, the man took the silver for himself and told the Xue family that Xue Guang had died. As they believed the report to be true and there were no news from Xue Guang, Mdm Zhang and Mdm Liu remarried after some time due to the family’s slide into poverty.

Only Mdm Wang chose to remain and take care of Xue Yi even though he was not her flesh and blood, together with an old servant Xue Bao. She weaved cloth to support Xue Yi through school. Xue Yi was however mocked by other children in school as the boy without a mother. Losing his temper, he took it out on Mdm Wang when he got home, saying that she had no right to punish him as she was not his mother. In fury, she slashed the cloth on her loom into two, signifying the serverance of their relationship, shocking Xue Yi and Xue Bao who hurriedly interceded on his young master’s behalf. Xue Yi came to his senses and promised to apply himself to his studies diligently, and even offered the cane to Mdm Wang to punish himself. In years to come, Xue Yi gained honours in the imperial examinations.

A movie based on the opera can be found here

Antique Display Shelf (博古架)

by Ang Yik Han

The term “bo gu” (博古) is derived from an inventory of antiques stored in the Xuanhe Palace commissioned by the Song Emperor Huizong. The published compilation consisting of 30 volumes was titled “bo gu tu”( 博古图) or diagrams of antiques. Subsequently, the shelves used in the Song palaces to display choice antiques came to be known as “bo gu” shelves. Over time, such shelves became popular outside of the royal court and appeared in the homes of the landed gentry, where they were used in studies and other private spaces to display antiques, curios and art pieces. Ranging in size from cabinets to small tabletop display racks, they still provide an Oriental touch for many homes today.

In Chinese art, antique display shelves containing various items with auspicious or felicitious connotations often appear as decorative motifs. However, few have been observed as tomb decorations at Bukit Brown. A rare pair can be seen at Ong Sam Leong’s tomb on the carved panels adjoining the Earth Deity’s altar.

The following objects can be seen on the panel on the left (from right to left)

- a vase with peony flowers – peace and prosperity.

- a tripod fruit platter containing a peach, a pumpkin and a citron – the fruits symbolise longevity, fertility (especially male offspring) and happiness. Collectively, they are known as the “3 Abundances”.

- what seems to be a Western clock – this may be an admonition to descendants to be mindful of time which waits for no man.

Those on the right panel are (from left to right)

- a censer with threading incense smoke above – fertility and generations which go on and on

- a container with a staff from which hangs a chime (bell) in the an “ao yu” or dragon fish – the character for chime in Mandarin is phonetically similar to “wishing” and the “ao yu” finds common use in an idiom which means “to be the best” (独占鳌头), so this could be an expression of wishing (descendants) to take the lead in all their endeavours

- a container with what seems to be a pair of forceps used with incense

- what looks like a branch from a plum tree – the plum blossom is admired for its resilience so this could be the implied meaning here

This is another example of the fine tomb sculpture which adds to the elegance of the tombs of Bukit Brown.

Editor’s Footnote : The same features were discovered on a tomb in the deep undergrowth of Lau Sua by Brownies exploring the area. Clothed in moss, the features are still discernible and the tomb itself is pretty grand!

Through time and distance, Grace Seah remembers and pays tribute to her grandparents buried in Bukit Brown.

“To forget one’s ancestors is to be a brook without a source, a tree without root”

(Chinese proverb)

As a young girl, I remember accompanying my parents to Bukit Brown Cemetery to pay respects to my late grandparents every Qing Ming. It was always an exciting time for me, folding the paper money into boat shapes, helping to trim the overgrown vegetation around the tombs, sweeping the surrounds and running around admiring the neighbouring tombs.

As the years went by, I gradually stopped attending to this annual ritual and left it entirely to my parents to do their filial duty on their own. My life took on a momentum of its own that left me with hardly any time to think about my ancestry and heritage and old traditions of my childhood. In time, I moved to another country to set up home there with my own family.

With the sense of loss I felt during the first few years of settling into my adopted country, there was renewed impetus to capture and treasure the precious memories of my Peranakan heritage and family mementos. The one memory I had of my grandparents was this beautiful old photo taken around the year 1934. It shows my paternal grandparents with my father, their youngest son and his 2 elder brothers.

I never grew up knowing my Mama and Kong Kong as they passed from this world before I could remember much. However, I have always felt particularly drawn to them through this photo. It was as if they were always smiling at me. I grew to love this special family photo with all my heart.

In this family photo are:

The matriarch and patriarch are my paternal grandparents. Both were buried in Bukit Brown. My father is the youngest boy in the picture. The dapper young gentleman in the black suit is his 2nd brother Tan Kim Teck and my 3rd uncle Tan Kim Cheng is in the middle. In those days daughters were not part of the family photos. One of my dad’s sisters Tan Imm Neo eventually married Cheang Theam Chu, son of Cheang Jim Chuan and grandson of Cheang Hong Lim.

My grandparents came from humble backgrounds but worked hard to raise a large family in the Peranakan tradition of those times. My grandfather passed away in 1946 and my grandmother single-handedly presided as the matriarch in the family until her death in 1964.

Through a series of coincidences and unexpected events, I was one day led to the amazing work being done by the Bukit Brown community to preserve the heritage that is Bukit Brown. Suddenly memories of all that I loved about Bukit Brown and memories of visits to my grandparents graves came rushing back at such a speed that it left me breathless. For reasons that only God and the Universe understand, I was given this one last chance to help locate the tombs of my grandparents before the government deadline of 31 Dec 2012.

It was a family photo that started the chain of events identifying my grandparents’ tombs. It was an unbelievable feeling when I finally reconnected with them. My 88-year-old father was also pleasantly surprised with the discovery, as with age, he had himself lost touch with his parents’ graves at BB.

I would like to think that Mama & Kong Kong had a hand in making all this happen. Who would have thought that this beautiful family photograph would be the key to ensuring that their earthly remains will finally be laid to rest permanently amongst the others, in a special place, never to be forgotten again.

Editors note : The tombs of Tan Keng Kiat and Chan Gin Neo are staked and will have to be exhumed to make way for the eight-lane highway. When Grace Seah posted a request on the Facebook page to help find their tombs, the response was near instantaneous, as Brownie Ee Hoon had remembered taking photos of the tombs and noting its unique features.

Recent Comments