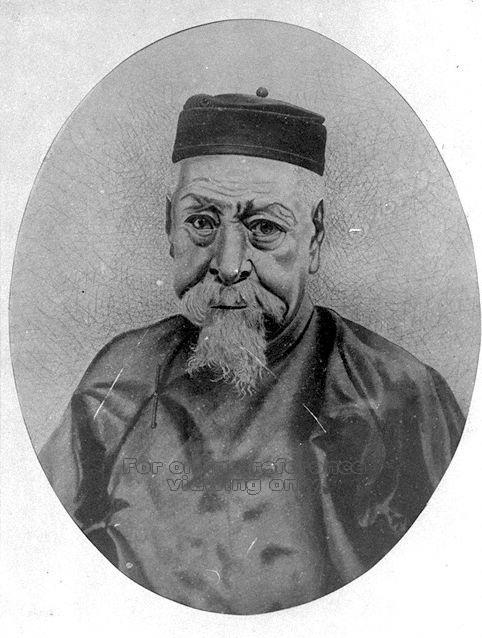

Seah Eu Chin (1805-1883)

Singapore’s Pioneer Gambier and Pepper Plantation King

Founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi

It started with a breaking news flash on the Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook page posted by Raymond Goh just after 2 pm on Friday 16 November 2012:

“Breaking news….the Goh Brothers have found the triple tomb of one of foremost Teochew pioneers of Singapore – Seah Eu Chin and his two wives, sisters of Tan Seng Poh. Details to follow…”

This was followed by the first photo of the tomb described as :

“Tomb of Seah Eu Chin, founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi, with his two wives Tan Beng Guat and Tan Beng Choo. Eu Chin passed away in 1883. We will take exact measurements tomorrow, but his tomb is believed to be as big as Ong Sam Leong.

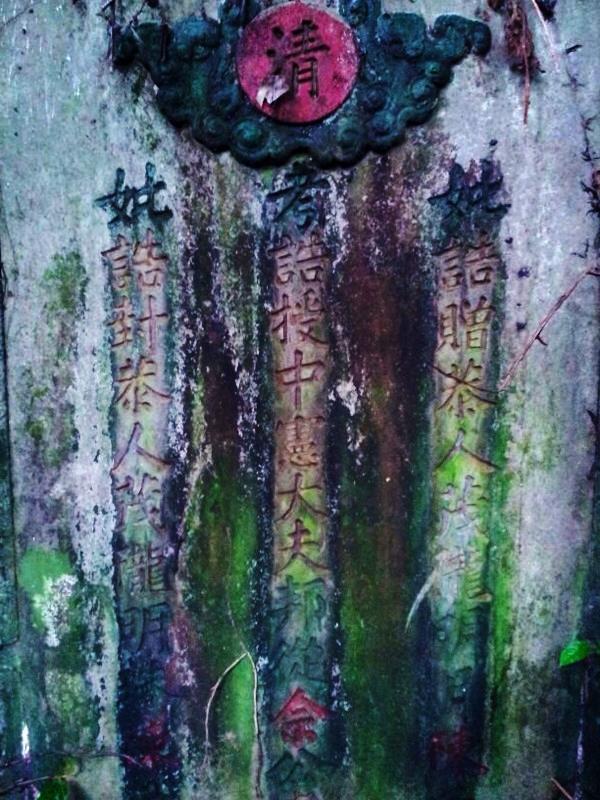

Tomb of Seah Eu Chin, founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi, with his two wives Tan Beng Guat and Tan Beng Choo. (photo Raymond Goh)

The tomb inscriptions included imperial titles, but Raymond reports, reading the inscriptions is proving a challenge as some of characters are missing. The lettering is done with some kind of metal which has fallen off.

This is Charles’ account of the search for Seah Eu Chin

“Like the previous finds of Ann Siang and the elder Gan, minutes before the find, there will be rain. For Seah, there were additional ‘help’. On the 1st day, a cobra reared its head preventing us from going one way. Another hissed to stop our tracks when we tried another way. And we met a monitor lizard on the start of the 3rd route. Thinking something’s wrong, we stopped our search minutes after we started. (After Eu Chin’s find, we knew we had went the wrong side of the hill then.) The 2nd day we tried a new location. The trek was smooth, and when rain fell, a sense of hope, and there rose a feeling that something was right. We found it in 10 minutes.”

The next morning, the Goh brothers were back at the grave and posted a photo of the grave in full glory:

The brothers have cleared a path towards the grave so his descendants, members of the Teochew Community and Brownies can visit later. The location of the grave is under wraps at the moment until such time as the descendant who made the request for help to find Seah Eu Chin is informed.

An extract on Seah Eu Chin from The Straits Times, 24 Sept 1932, Page 12

Chinese Benefactor of 1845 – Ngee Ann Kongsi:

In or about the year 1845 the late Seah Eu Chin, at that time a prominent Teochew merchant in Singapore and 12 other Teochew merchants then in Singapore, promoted the formation of a fund for the propagation and observance in Singapore of the doctrines, ceremonies, rites and customs of the chinese religions as observed by the Teochew community, a community of Chinese originating from certain districts in the Kwantung Province of China, and for other charitable purposes for the benefit of the members for the time being in Singapore of the Teochew community…

There is a blog post on Seah Eu Chin here.

Related Post:

The Dragon King, The Emperor and a New Wife….

The most spectacular cluster of tombs at Bukit Brown belonging to Ong Sam Leong and family is resplendent with carved panels which depict stories from epic Chinese classics.

Ang Yik Han shares 2 panels of a story in the Chinese classic “Journey to the West”

Panel 1 from:

“After touring the underworld, the spirit of Emperor Taizong returns”

游地府太宗还魂

Underworld official adds 2 strokes to character as Emperor flanked by 2 companions look on (photo Yik Han)

Background: One of the dragon kings ran afoul of celestial law and was sentenced to be executed by an official at the Tang court. The desperate dragon turned to the then Emperor, Li Shiming (李世民), and beseeches him not to allow the official to go to sleep as that was the time the deed was supposed to be done. The Emperor agreed to help and promptly summoned the official to play chess overnight with him. During the game however, the official dozed off and in that short interval his spirit went off and slew the dragon king.

进瓜果刘全续配

by Gan Su-lin and Catherine Lim

The tomb staked 1888 or rather its companion is used as an illustration in the LTA sign boards at Bukit Brown to explain to the public how to look out for and identify whether an ancestor could be affected by the 8 lane highway that is going to be built through Bukit Brown.

The resident of Tomb 1888 was exhumed on Thursday 21 June 2012 by his descendant, a great grandson who has requested privacy of identity but was kind enough to allow Su-lin and me a chance to document and observe the exhumation from start to end.

On that day, we were told there were 4 exhumations and the following day, 11 were slated. We know this because exhumations has officialdom behind it. They have to be registered with NEA (National Environment Agency) which sends inspectors to spot check that it is conducted properly. There are papers to be signed and processed, but the tomb keepers are familiar with the procedure and cut out as much of the paper work as possible for the descendent. A note here to say that the companion tomb next to 1888 is not occupied which is not uncommon in Bukit Brown. The one beside it was most probably prepared for a spouse but who was not buried there for a variety reasons which we will not speculate on. The descendant was alerted to the existence of his great grandfather’s tomb only last year by Raymond Goh and proceeded to “refurbish” the tomb before news was released that the grave was affected by highway.

The exhumation of staked tomb 1888 started at 8 am with prayers and the digging started about 20 minutes later together with the separation of the tombstone from the backing which is necessary to release the spirit, a way of notifying the “resident”, he is moving house. The latter required the wielding of the mallet against stone which was heart wrenching to observe even for an outsider. The exhumation proved longer than the anticipated one hour because the grave was so well encrypted with granite slabs and brickwork and the coffin so well kept that it required a chainsaw to cut the opening. It was a “clean” exhumation, with remains of bones and nothing else.

Preparing to chant prays with incense, a bell and a dorje or vajra– ” thunderbolt” which is used in Tibetan Buddhism. The brown portfolio is an ipad which had been loaded up with the chants (photo Catherine Lim)

Separating the tombstone from the backing “releases the spirit” notifies the long time resident, he is moving home, the digging starts in tandem (photo Catherine Lim)

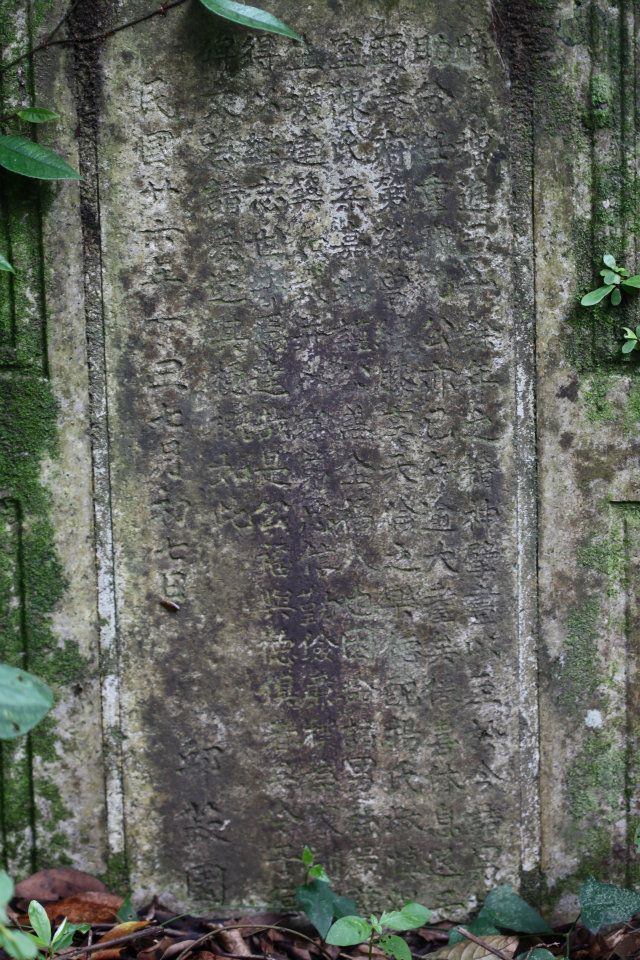

A valuable piece of inscription on the lives and times of the ancestor which is saved. (photo Catherine Lim)

Gan Su -lin (who documented) weighs in with Lim Ah Chye (tomb keeper) what to expect. (photo Catherine Lim)

Revealing the coffin, intact and impenetrable after more than 70 years and some excellent brick work that drew the admiration of the grave diggers (photo Gan S-lin)

The first yield is a termites nest which Su Lin picked up thinking it might be the discovery of truffles in Singapore ( photo Gan Su-lin)

The second yield, teacups which survived the long internment, duly collected and delivered to documentation team office (photo Gan Su-lin)

The exhumed ancestor must not be exposed to the sunlight.The use of the umbrella is symbolic and will shade the ancestor right up to the placement at the final resting place The remains were rinsed prior to transfer to crematorium with Chinese wine.(photo Gan Su-lin)

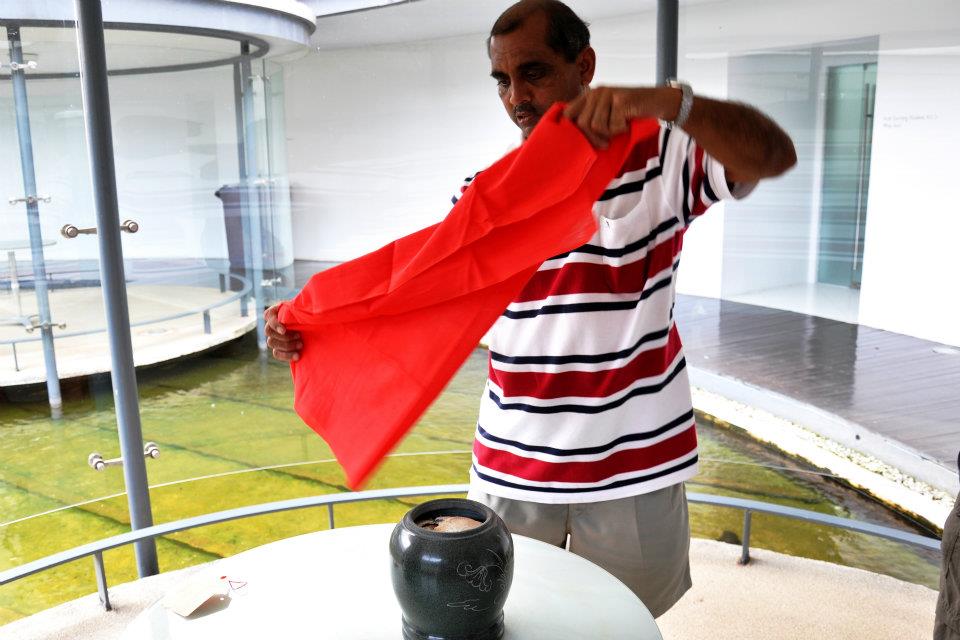

Ah Nan, who speaks fluent Hokkien presides over transfer of ashes to urn with the greatest of respect and meticulous attention ( photo Gan Su-lin)

One last look at the Crematorium before the ancestor was brought to the family temple (photo Catherine Lim)

The exhumation began at 8 am. The gravediggers reached the granite slabs an hour later. The remains were exhumed just after 10am and transported to the crematorium about 10.30. The remains were ready for collection at 11.30am. By 1 pm, the ancestor was” laid to rest” in the family temple.

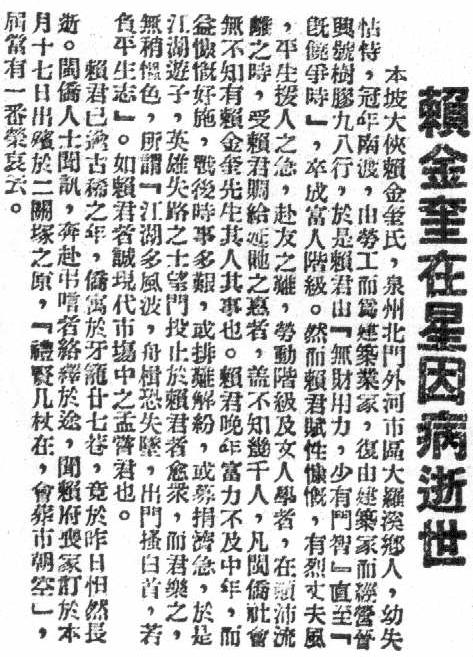

Luah Kim Kway (赖金奎) the Chivalrous

by Ang Yik Han

On first impression, his is a typical story of a poor migrant made good. Orphaned when young, Luah Kim Kway left for the Nanyang at the age of 19 to seek his fortune. Like other uneducated migrants who toiled unceasingly, he was at various times a coolie, a hawker and a miner before hitting his first pot of gold as a building contractor. Subsequently, he branched out into the rubber and import/export businesses. As a community leader, he was one of the founders of the Chin Kang Association, a locality association catering to Hokkiens from Chin Kang (晋江 – “Jin Jiang” in pinyin) county in Fujian province. He served as the association’s vice chairman for many years and was actively involved in its mutual aid group and school.

Many also knew Mr Luah, or Kway Pek (“Uncle Kway” in Hokkien) as he was respectfully called, as a powerful secret society headman.

A coolie newly arrived in Singapore found himself amongst strangers in a strange land. Very often, there was no one he could trust and turn to for support other than clansmen or associates from his home village. Thus was born the “coolie keng” or coolie quarters which provided shelter, occupational support and fellowship for coolies sharing a common origin. In return for a small sum every month, the coolie had a space where he could sleep and stow the trunk containing his meagre belongings.

Due to the nature of migrant society then, differences were often settled by force of arms and numbers counted. Members of coolie kengs banded together for self protection and over time coolie kengs became synonymous with secret societies. There were frequent clashes amongst rival coolie kengs over turf issues. Some of them even evolved into criminal organisations which were a constant headache to the colonial authorities.

Many of the Chin Kang Hokkiens who arrived in Singapore in the early days worked as lightermen and dock labourers, traditional occupations as their homeland was by the sea. Like coolies from other regions, they were organised along the lines of the coolie kengs they belonged to. According to the Chin Kang Association’s records, at one point there were more than sixty coolie kengs in town set up by Hokkiens from Chin Kang. In areas like Bali Lane, there were Chin Kang enclaves due to the presence of numerous coolie kengs.

The Puah Kor (Hokkien for八股 or “8 formations”) was a confederation of societies largely made up of Chin Kang coolie kengs with a sprinkling of non-Chin Kang groups. Unlike other secret societies which were involved in activities of a criminal nature, the Puah Kor was known for its tight discipline. It did not actively seek conflicts with other groups and acted only to protect its members’ interests. Mr Luah was the leader of the Puah Kor, a position which must have reinforced his ability to arbitrate in conflicts between Chin Kang coolie kengs as well as within the larger Chinese community in his other role as a representative of the Chin Kang Association.

An anecdote demonstrates the extent of his influence. After the war, a Chinese basketball team from Manila composed largely of Chin Kang Hokkiens was in Singapore on a fund raising campaign. For some reason, some factions took a dislike to the team’s captain and there were rumours floating that the coming matches would be violently disrupted. One of the worried organisers took the matter to Mr Luah. Mr Luah only commented in his quiet manner, “Shall we have some fried bee hoon?” During the meal, the conversation ranged far and wide with many things discussed but not the subject of the visit. As the guest was about to take his leave, Mr Luah told him, “Give me sixty tickets for tonight’s game.” That night, two hundred stout men turned up for the game at Gay World which proceeded peacefully. The following evenings were without incident as well.

For obvious reasons, it is almost impossible to obtain documented accounts of secret society personalities. Mr Luah was an exception. His contributions and high regard in society were acknowledged in an obituary published in the Nanyang Siang Pau when he passed away in 1951. It described him as a principled man whom others trusted and mentioned his generosity to those in need. As an epitaph, a phrase used by the paper, “a chivalrous man” (大侠) would be most fitting.

Mr Luah’s final resting place is by the side of the road in Hill 3, a short distance from Tan Chor Lam’s grave.

References:

- 新加坡晋江会馆纪念特刊(1918-1978)[Commemorative Publication, 1918-1978]

- 新加坡晋江会馆庆祝成立80周年暨互助部成立52周年纪念特刊 [80th Anniversary and Mutual-Aid Section’s 52nd Anniversary Souvenir Magazine]

- Interview with Ho Bee Swee, Collection of Oral History Recording Database

Ever since they were “discovered” in early 2012 – when volunteer guides started to trail Raymond Goh on his missions to help descendents find ancestors in Bukit Brown – they have been a talking point.

Dubbed “Naked Angels” by I believe one among the community, we speculated on their genesis and gender. And sometimes wondered about the ancestry behind the double tomb which is also guarded by a pair of sikh guards.

No one had visited in a very long time. To visit the tomb means being subject to being bitten not just by mozzies but also the most vengeful ants to be found thus far, for having their territory disturbed.

But just two weeks ago, a family contacted Raymond Goh whom he believed were the family who “owned” the angels. The community was excited. An appointment was made with Raymond for Saturday May 12 th. The pair of cousins who turned up after lunch time that day were perhaps a little taken back by Raymond’s entourage of five. If there were, they took it in their stride. At least two of the volunteers were familiar to them as they had attended a guided a tour just the previous week.

Armed with their family tree, Raymond helped “reconnect” them their great grandfather and his 3 wives, and their grandfather who died during the Japanese war. A grand total of 5 tombs!

This is your great grandfather Teo Chin Chay buried together with his first wife Gan Chwee Sian who was China born and had bound feet (photo Catherine Lim)

The inscriptions on the tomb stone are deeply carved and clear to read the names (photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

“Now let’s look for the other two wives. See the plot number again” with tomb keeper Lim in blue (photo Catherine Lim)

Raymond had already bounded up the other side of the hill and penetrated deep into the bush (photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

“It took me quite some time to find it, but I have now familiarized myself with the pauper divisions, so much so that the tombkeepers themselves ask my assistance if they encounter difficult to find tombs in pauper divisions. This one is in Blk 3 Div 11, in the depths of the forest.” Raymond Goh

So ends another fruitful afternoon for Khoo Ee Hoon, Peter Pak, Chew Keng Kiat with Raymond Goh. But we still don’t know much about how it came to be that a wealthy trader and businessman by the name of Teo Chin Chay came to have a pair of such unusual angels guarding his tomb. Could it be a Western take to Golden Boy and Jade Girl? The mystery continues.

Reported by Catherine Lim who was there but did not go bush bashing up the hill!

Alex’s Story Part 1

Compiled by Catherine Lim

In 1940, when Lim Sian Chin was only 6 months old, his mother passed away from a mysterious illness. Tan Tee Teo 陳甜桃; was only 23 years old.

On 2nd April, 2012, exactly 72 years to the date of Tan’s death (according to the lunar calendar) Lim Sian Chin, with his wife Hai Lian and 2 sons, Alex and Yong Beng paid what could be their last Qing Ming respects to her. (Roger, the middle son of Lim’s was in Dubai) Staked grave 3716 is one of nearly 4000 graves which lie in the way of an 8 lane highway that the government plans to build that will slice Bukit Brown Cemetery into half.

This is the photo essay of the Lims’ Qing Ming 2012 which was also covered by the documentation team led by Hui Yew Foong. It is composed from the view point of the eldest son, Alex.

” I remember back then when I was this nigh high, playing here among the lallang and the mozzies are still here ….” (photo Catherine Lim)

The Lim family were Taoist practitioners. In recent years, they have become Buddhists, as father believes after a period of time, the departed are already well and truly reincarnated. So offerings are “symbolic”

A unique way of wedging coloured paper through grass stalks so it won’t fly away (photo Catherine Lim)

This tradition comes from a Han emperor who after a long stint away from at war , returned home to pay respects to his parents. Their graves had become overgrown. So he decided to throw paper in 5 cardinal directions and where they landed and stayed, that would be where their graves were. A stone was used to wedge the paper to their tomb stones (that is why you still see stones on top of tombstones, it shows descendents have paid a visit.) Alex has his own unique way of “marking” the spot.

Post Script to Tan Tee Neo : The widower of Tan Tee Neo was to later marry her much younger sister sometime during or after World War 2. It was a fruitful union which resulted in half siblings for Lim and that branch of the family too continue to honour their late aunt at Qing Ming.

Alex’s story continues in Part II coming up soon where he pays his respect to his great great grandparents who are also buried in Bukit Brown. They are Lim Kee Tong 林箕當, Neo Kim 梁金. Find out more about the part Lim Kee Tong played in the setting up of a free school and a temple.

My Ancestry at Bukit Brown by Lim Su Min.

Saturday 21 April,9 am – 11 am.

I am Lim Su Min, a retired doctor and grandfather to 5 children. I have identified 7 direct ancestors buried at Bukit Brown going back 5 generations for me, 7 generations for my grandchildren. My ancestors reposing at Bukit Brown include the parents and grandparents of Dr. Lim Boon Keng and Tan Tock Seng’s son and grandson, Tan Kim Ching and Tan Boo Liat respectively.

Dr. Lim Boon Keng himself was buried at Bidadari, disintered and ashes at Mt Vernon.

Tan Tock Seng’s tomb cluster stands out along Outram Road. Tan Boo Liat is the father of my grandmother Polly Tan, and Tan Kim Ching is grandfather of Tan Boo Liat. Into this alliance of two great families is the Seow connection. Mrs Seow Watt Chye is mother of my grandfather Seow Poh Leng;

Confused? Let me, Lim Su Min attempt to unravel for you my ancestry by sharing with

you personal stories on my heritage run to visit the tombs of my direct ancestors who are buried in Bukit Brown, share something about the surrounding habitat and some of the neighbours who are buried in the same location. I have invited tomb whisperer Raymond Goh to share some of his insights.

The Route for Lim Su Min’s Ancestry Trail at Bukit Brown Saturday 21st April 2012 covers the TAN- SEOW- LIM Family Connection scattered over various blocks in Bukit Brown.

The tomb stops include :

Tan Kim Ching, GGGGF (great,great,great, grandfather)

(neighbour to Cheang Hong Lim )

Seow Watt Chye GGM (great grandmother)

Tan Boo Liat GGF

Mr & Mrs Lim Mah Peng GGGGF/M

Mr & Mrs Lim Thean Geow GGGF/M

Highlights:

Tan Kim Ching (陳金鐘) (1829 -1892. ) Tan Tock Seng’s eldest son who recommended Anna Leonowens, as the teacher for children of King Mongkut of Siam ( King Rama IV) Buried in Changi, transferred to Bukit Brown (1940). One of Singapore’s earliest “diplomats” and much respected in the Siam court.

Tan Boo Liat, (1875-1934) built his home Golden Bell Mansion,10 Pender Road on Mount Faber, naming it after his grandfather. He was a strong supporter of Dr. Sun Yat-sen and member of the Singapore T’ung Meng Hui along with Lim Boon Keng. In 1920 he was awarded the title Phra Anukul Sayamkich by the Siam court.

Tan Boo Liat’s daughter Polly was the template for Emily of Emerald Hill, written by my sister Stella Kon ( nee Lim). To know that Polly was the niece who eventually married her aunt’s husband 12 years her senior, when the aunt passed away is to understand the complex forces at play in creating “Emily”

By a strange coincidence, different forms of mosaic art flourished in the West and East independently of each other. The renowned Byzantine mosaics have their parallels in the “jian nian (剪黏)” or cut and paste mosaic sculptures of Southern China. This decorative technique is widely used in traditional architecture, particularly in the elaborate sculptures adorning the roofs of temples in the Fujian and Chaozhou regions. Migrants from these regions brought the technique abroad and mosaic sculptures can be seen in many traditional buildings in Singapore and Malaysia.

A cemetery is not the usual place to find an ornate temple roof but the art of “jian nian” has nevertheless managed to find its way into Bukit Brown. On Hill 4, at the tomb of Mdm Yeoh Siew Kheng (commonly known as the “5 cats” tomb due to the presence of 5 lions), a lavish display of “jian nian” mosaics can be seen. There are the five lions, a pair of male attendants and tableaux featuring the 8 immortals. Even the Chinese characters of the tomb couplets are mosaics.

Time and the elements have not been kind to these art pieces but enough remain to give a hint of the once gay colours and resplendent forms.

So far, this is the only instance of “jian nian” mosaic sculptures found in Bukit Brown. With so many tombs unexplored there may be more surprises in store.

The search for a long lost aunt buried at Bukit Brown began last year, when Miho Tan requested the help of Raymond and Charles Goh to locate his father’s sister. She provided these details

Name : Tan Lay Chee

Grave : C III, 857

Age : 18

Year of death : December 1932

Following up this year, Raymond found Miho’s aunt and from her tomb inscription discerned that Tan Lay Chee died at the young age of 17 on Christmas Day, 1932. She was unmarried, but a boy was inscribed in the tomb as a “stepson”. According to the information Raymond gathered – the burial registry does record cause of death – she died of mo tan, a kind of high fever.

He recalls her family visiting her tomb a few years ago but they had forgotten the route as the surrounds had become quite inaccessible due to fallen trees and overgrowth.

The family of Tan Lay Chee visited her soon after Raymond located her tomb, and brother Lay Chee connected once more with his elder sister.

Also buried at Bukit Brown, is Miho’s grandfather. Miho captured a family visit to his tomb in February in a video here

Grandfather Tan Choon Kiat was a book keeper and died at the relatively young age of 51 years old.

Miho’s grandmother, Lim Geok Yan survived her husband by more than 30 years. She died just past her 80th birthday and her ashes are interred at Bright Hill Temple at Sin Ming. Her grandfather’s tomb, is a double tomb but he rests alone. It can be deduced that his wife was originally intended to rest side by side with him.

The life and times of Lim Geok Yan is deeply etched in the mind of Miho’s father. He was the youngest of 8 children, 6 boys and 2 girls. We know she had to bury a child and as a young widow life must have been tough. Miho recalls what his father shared with him:

“Being a tough nonya my Dad says she had to pawn her jewellery bit by bit in order to maintain the household , the daily expense had to cover (they lived in a traditional Peranankan house), around 16 members which included 7 “cha bor kan” – Hokkien for maids. She was a strict mother too (Dad did not elaborate). I’m sure she would have been been a strict grandmother too and maybe I’ll be allowed to wear traditional Baba wear on special days.”

Miho remembers being taken to the Baba House, where her father pointed to a portrait of Lim Ho Puan hanging there, and he said to Miho, “there, that is your chor kong – (Hokkien for great grandfather)”

Lim Ho Puan is among a list of luminaries which include Lim Boon Keng, Lim Nee Soon and Lim Yew Hock named in the book Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, Business, Politics and Socio Economic Change, 1945 – 1967

A simple tomb of a long lost aunt, has become for the niece who never knew her, a touch stone revealing a family history which is both personal and historical.

几枚白石伴青珉,

小筑坟莹隔岁春

地下有灵相谅解,

迟工原是为家贫.

A few pieces of white rock accompany the green stone,

A little grave built but alas late one year

My dear I hope you can understand the reason,

I am late to build because of my poverty.

(Khoo Seok Wan (1874-1941) in memory of his wife, Lu Jie (陆结)

He was a Confucian scholar, a political activist in revolutionary China, a prominent community leader in Singapore and an early advocate for education for girls who helped set up the Singapore Chinese Girls School.

Born into a wealthy merchant family, Khoo’s fortunes waxed and waned because of his extravagant life style ( he was known to be a generous host) and the over extension of his funding activities to revolutionary causes. But embedded in his life is a love story which captured the heart of Bukit Brown resident tomb whisperer Raymond Goh; he was determined to find his grave.

When Khoo Seok Wan’s wife died in 1936 at the age of 44, his fortunes were on the wane and he was bankrupted. He could not afford a tombstone for his wife whom he buried in Bukit Brown. So he buried his own tooth with her and when he could afford it the next year also constructed his own tombstone in preparation to be reunited her one day. The poem was penned to mark the occasion.

Khoo was born in Fujian, China, and followed his mother to Macau before he joined his father in Singapore in 1881. His father, Khoo Cheng Tiong (邱正忠), was a successful rice merchant and prominent community leader in Singapore. Khoo was schooled in traditional Confucian education, and when he was 15 years old, he went back to his hometown to prepare for the Chinese imperial examinations. He passed the district and provincial examinations to attain the level of a juren (举人) that qualified him as a candidate for the central government imperial examinations in Beijing, but he failed in that attempt in 1895 and returned to Singapore.

Khoo suffered from leprosy and lived his last years on the generosity of his friends. He died in Singapore at the age of 68 on 1 December 1941.

He was buried in Bukit Brown cemetery beside his wife. Earlier this year, Raymond Goh finally tracked down the tombstone Khoo built for himself and his wife from records in the Burial Register lodged with the National Archives. Khoo Seok Wan’s tomb is in Blk 4 Section C, is in the path of new dual 4 lane road.

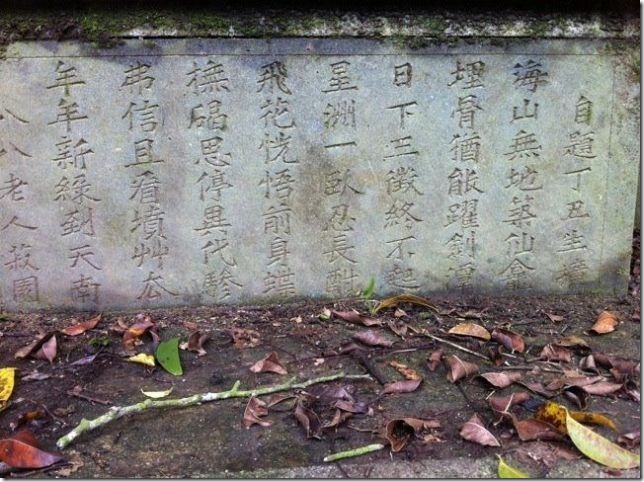

Khoo Seok Wan “live” tomb, inscribed on the altar is his epithet which he penned himself (photo:Raymond Goh)

海山無地築仙龛

… How can the buried bones leap across the sword lake

日下三徵終不起

Even if you beckon 3 times, I could no longer arise

That lay in Singapore enduring long thirst

Flying flowers realized their butterfly past life

Caressing the epigraph, thoughts stop and future generations

If you don’t believe just look at the tomb grass

88 old man Seok Wan

I stand before him, silent, in respect and awe.

His genes embedded in every cell of mine

We are bonded though the course of time.

A white stake declares a foreboding future

His eyeless sockets shedding copious tears

That eight lane highway: unspoken fears

“Could you not ask them to let us rest in peace”

His silenced tongue in eloquence loudly says

His bony hands grasp me in one last fond embrace.

by Lim Su Min 林蘇民 in tribute.

The prolific Khoo is responsible for composing epithets for luminaries buried at Bukit Brown. Among them the father of Khoo Teck Puat, Khoo Yang Thin. His epithet is an exhortation to the descendents through a list of things to do to live a good, honest and honorable life.

Discernible beneath the grime there is true grit Khoo Yang Thin’s grave can be found in group 12 on the map (photo Perry Tan)

Another example is the epithet for Wee Teck Seng’s tomb (just below Gan Eng Seng):

Khoo Seok Wan was also responsible for popularizing the term Sin Chew which is a sobriquet for “Singapore” (translated) Khoo writes: Singapore is an island surrounded by the sea, and with vessels and boats large and small anchored around it; the glitter of artificial lights at night are like a crown of illuminated stars (“星”) when viewed from afar. “洲” (zhou, island) and “舟” (zhou, boat) are homonyms: while the boat lights are like stars, those on the island are like the Big Dipper to accentuate the constellation. This is why the term “Sin Chew” is widely known by folks here and afar.

Editor’s note: In the first posting of this article, Lim Su Min our tea master, believed Khoo Seok Wan to be his great great grandfather based on initial evidence. Further investigation has shown this trail to be false. But in the spirit of paying tribute to Khoo Seok Wan the poet, we are leaving in this post the poem composed by Su Min.

Recent Comments