By Serene Tan

Not long after my dad passed away in 2011, the government announced plans for an 8 lane highway that would cut through Bukit Brown, and graves in the way would have to be exhumed.

The news of the highway triggered a memory. The last time I visited my grandpa’s tomb was more than 40 years ago when I was a young girl. I could vividly recall my grandpa’s tomb at Bukit Brown. Concerned it might be affected, I realised it was time to visit him.

I arranged with my cousin to visit the grave for the ‘Qing Ming’ festival the next year, 2012. It was a relief to learn that his grave was not staked for exhumation. But to my dismay, the tomb was in a dilapidated condition. The tomb had been neglected for more than 15 years after my dad suffered a massive stroke which left him paralyzed and wheel chair bound.

It dawned on me then, that I now had the responsibility to carry on my father’s duty to ‘sweep’ grandpa’s tomb during the ‘Qing Ming’ festival. His tombstone spoke to my roots.

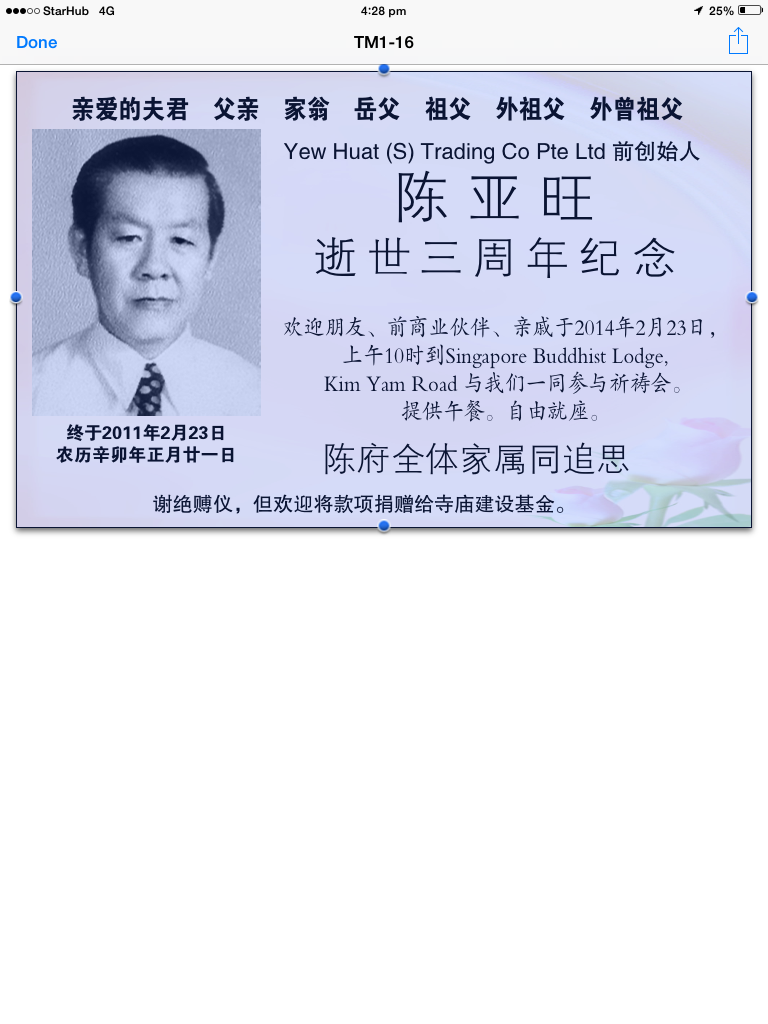

Inscribed on the tombstone was my ancestral hometown , Kimen, my grandfather’s death date, 1937, and the names of his children. My father was the only son. For the first time I came to know my father’s birth name 陈天吉, Tan Tien Kiat, inscribed on the tomb. My grandpa passed away when my dad was only five and dad changed to a simpler name, 陈 亞 旺, Tan Ah Ong

I arranged with a contractor to renovate my grandpa’s tomb, and before work started, I decided it was also time to visit my ancestral home in Kinmen, Taiwan . Unconsciously, I think I was seeking the blessings of my father and grandfather.

My grandpa Tan Teow Meng (陈 朝 明 )left his home in Kinmen, more than 100 years ago. In Singapore, I was told he worked as a lorry driver and died because of a bout of high fever.

My father had attempted to visit his ancestral home, thrice in the 80s. Kinmen is a small archipelago of islands and at that time was under a military administration because of fighting with China. The only means of transport then was by military helicopter. Visitors to the island were restricted but because Dad could claim to be descended from his ancestors in Kinmen, getting permission was not the problem. Each time, it was bad weather which prevented my father’s flight on the helicopter from taking off from mainland Taiwan.

He was so close and yet so far. I felt deeply the pain of his disappointment. Dad subsequently passed away, without fulfilling his dream.

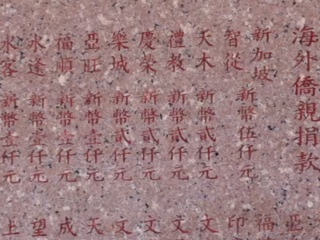

It was in my ancestral village of Houshan (后山), now known as Bishan, that I learned my father had contributed funds to two temples. His name was inscribed on the list of donors for both temples. This one is from the smaller village temple 陈氏宗祠

I placed my father’s photo as close as I could to the inscription of his name among the temple’s donor list (photo Serene Tan)

My heart swelled with pride. There is an old Chinese saying “Drink Water, But Remember the Source”- “饮水思源” . My father, although he was not able to visit his ancestral home, never forgot his roots.

The family home and land in Kinmen, remains abandoned. But at home in Singapore, my grandpa’s tomb has been rebuilt with granite stone and fresh inscriptions in gold dust. My grandpa had a humble life his son – my father – worked hard and became a successful business man and never forgot his father. I have always admired my father for his work ethic and persistence.

So as I marked Qing Ming at my grandpa’s new “home” after my visit to Kinmen, I felt happy and blessed to have been able to accomplish my father’s dream of visiting our ancestral home.

***

My journey to my ancestral home in Kinmen in a photo essay.

My ancestral home and land, abandoned. Relatives I met told me, the home was occupied by troops during the conflict with China and they also dismantled the wooden structures to build their bunkers. ( photo Serene Tan)

The village temple 陈氏宗祠

The temple serves residents nearby to offer prayers anytime as and when they deem necessary. (陈氏宗祠)

My father also donated to the larger Tan clan ancestral temple, 陈氏 家廟. Unlike the village temple, it’s opened only for certain festival celebrations and entry restricted to only male descendants. I was privileged to be granted permission to enter, as an exception.

- In the courtyard of the Tan temple, holding a photo of my father (photo Serene Tan)

My father’s name 亜 旺 on the donors list.

4th from left is my father’s name on the list of donors from Singapore to the Tan temple (photo Serene Tan)

Meeting my relatives for the first time, I learned my great grandfather’s name is 陈 正. So he is the earliest of my ancestors I have come to know.

I will be marking my father’s third death anniversary at the Singapore Buddhist Lodge, 17-19 Kim Yam Road on 23 Feb 2014 at 10 am. Friends and relatives are welcome to join us in prayers.

Chew Chai Pin

(b. 11 November 1911 – d. 13 June 1941)

Among the 4,000 graves which will have to be exhumed to make way for the highway is that of Chew Chai Pin (# 1253)

The Grave of Chew Chai Pin ( photo credit : The Bukit Brown Documentation Project)

Chew Chai Pin was one of three founders of the Chinese High School in Batu Pahat. Unlike the other prominent Chinese men who contributed to the school, Chew was not well known then in the community. He held the concurrent position of director and teacher of the Ayer Hitam School. But he was soon to answer a higher calling.

On March 6, 1940, Chew went to China from Singapore to Yangon and China, to visit and give moral support to the Nanyang volunteer mechanics and drivers, as well as civilians and troops. The Nanyang Volunteers were recruited and trained from South East Asia, to transport war and logistic supplies through the notorious China-Burma highway to sustain China’s war effort against the invading Japanese. Chew represented Batu Pahat as part of a deputation comprising of representatives from the overseas Chinese communities of South East Asia.

But on March 29 1940, the vehicle he was in overturned and he sustained serious injury to his spinal cord. He was warded at a hospital at Xiaguan (Yunnan) while the rest of the deputation proceeded to their destinations. He was visited by none other than Tan Kah Kee, who was instrumental in galvanizing the support of the overseas Chinese in Nanyang (South East Asia) for the second Sino-Japanese War. Tan made arrangements to have Chew sent to Yangon for treatment as the doctors in Xiaguan were unable to heal him. Chew’s legs were numb and he could not walk for more than a year. Chew also received a letter of consolation from the Commander-in-Chief of the war and leader of the Kuomintang , Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek.

On March 4th of 1941, a year after his accident, an arrangement was made for him be transported to Singapore for treatment. Just when many thought Chew would recover, he died in Singapore on June 13, 1941 at 0615 hours. It was said that his funeral in Singapore was attended by more than 400 people. He was hailed in both Singapore and Malaysia as a patriot who sacrificed his life for China.

An obituary in the Nanyang Siang Pau to the memory of Mr Chew Chai Pin proclaims: “He Died for his Country”

On his deathbed, he urged his compatriots to spare no effort for China’s salvation. He said:

“I am ashamed to have done nothing in service of my country. How can I die without doing anything for the motherland? I must do something for the nation when I come back in another life.” Chew Chai Pin.

Chew was just 30 years old when he died.

Tan Kah Kee wrote in his memoirs that when the deputation left Singapore by ship on the 6th of March, it was sent off by a crowd in high spirits. Only Chew’s mother and wife were weeping. Somebody observed to Tan, that the deputation would be away for only 3 months and it was an honour to be a delegate, so even though one could excuse Chew’s mother as she was of an older generation, his wife who was educated and a teacher was showing too much emotion. After seeing Chew in hospital six months after his accident, when he could not be cured by the doctors there, Tan Kah Kee remarked that it seemed the mother and wife had been prescient of what was to come at the point of parting.

Chew was born on 11/11/11 in the Hokkien Province, Tong An County, Au To village. He married in November 1937, and was childless at the time of his death. After he passed away, his parents adopted a son on his behalf.

postscript : Chew Chai Pin’s grave has been claimed.

***

Source: From the blog of 沈志堅’who is a teacher at Chinese High School in Batu Pahat. (Translated by Fabian Tee)

Additional information from the Memoirs of Tan Kah Kee

On 2nd January, 2014, June Tan witnessed and photo documented the exhumation of her grandfather, Ong Kim Soon. She also shared with us the testimonial of how a promise was fulfilled to carry on the lineage of another family. It speaks to men and women of honour and ties of kinship which live on till today.

The exhumation of Ong Kim Soon begins, after the family conducted their pre- exhumation rituals (photo June Tan)

***

By June Tan

My grandfather was an ordinary man. He worked hard to make ends meet and was an honest man of principles. When he passed away at the age of 47 , he left behind his wife & 6 children aged between 6-22 years old then.

The story I want to share of my grandfather has to start from my great great grandparents.

My great great grandfather Ng died at a very young age. He was in his 20s then. He left behind his wife but no descendants. The women of that era usually did not remarry if their husband passed on. It was deemed to be their duties to take care of their in- laws .

However, my great great grandmother was a young lady in the prime of her life at that time. Her mother- in- law decided that she should not stay as a widow and allowed her to remarry. She, however, set a condition for the man (suramed Ong) who was to marry her- that the first son born by them had to take the surname “Ng” (黄). As a gratitude to the old lady, they readily agreed.

Soon after, my great grandfather was born and he took the Ng surname. However, great great grandfather Ong soon fell very ill and with his wife they were unable to produce a 2nd child. Their son, my great grandfather had no option but to reinstate his surname to Ong in order to perpetuate the Ong family line.

The older generation is a generation of principles. It was resolved that the next male child born in the family will carry the surname of Ng to honour the promise of my great great grandparents.

Years later, my grandfather was born and he adopted the “Ng” (黄) surname. In fact, of the 3 sons born in that generation, my grandfather and his 2nd brother took on the Ng surname as a gratitude to the Ng family.

At age 47, my grandfather passed away. All that he left behind was a meagre sum of S$24. The family was faced with the task of paying for a decent burial place.

Seh Ong Sua (which adjoins Bukit Brown) was the only cemetery with free burial grounds available for the Ong descendents . My grandfather’s brothers, my grand uncles, approached the person in charge of the Ong Clan then. However, only descendants of the Ong clan could be buried there. After hearing the origins of my grandfather’s surname, the Ong clan agreed to accord him a burial ground in Seh Ong on condition that that he had to use his Ong surname on the headstone of his grave.

Hence, the surname on his tomb is Ong (王) whereas his children will continue to take the Ng surname.

For these reasons, my great grandmother had “set” a rule for my mum’s generation that they are allowed to marry Ngs’ but not Ongs’ as that is the origin of their bloodline.

***

A few photos from June Tan’s album of her grandfather’s exhumation. The coffin was fully intact and the set of bones, nearly complete. With her permission, the complete album which she has captioned as a photo essay, is available here

The remains after the coffin (which was fully intact) was opened with an electric saw (photo June Tan)

The bones are washed with white wine as required by traditional exhumation practices. (photo June Tan)

***

Ong Kim Soon has moved to Yishun Columbarium. Rest in Peace.

Editor’s note: We would like to thank June Tan for sharing her photos of her grandfather’s exhumation and her family story with us. If you are a descendant who has ancestors staked for exhumation, please share your story with us.

Email us: a.t.bukitbrown@gmail.com

You can read about another first hand account by a grandson, who witnessed his grandfather’s and aunt’s exhumations, here

A personal account by Aylwin Tan who witnessed the exhumation of his grandfather and aunt at Bukit Brown on the morning of Wednesday, 8th January,2014.

***

I received a phone call from the exhumation office about 1.5 hours after I had registered. Picked my Dad up and went directly to the gravesite.

The green tentage is that of my aunt Tan Siok Hwa (aged 10) and the grey is my grandpa, Tan Cheng Moh. Both were killed during a Japanese raid; a bomber scored a direct hit on the bomb shelter where my grandpa had put his entire family, including his close relatives. Apparently, grandpa’s thinking was that they should all stick together and if they all died, so be it.

Their funerals were carried out in haste. A number of traditions were abandoned for fear of being caught out in the open by the Japanese bombers e.g. mourners alighting to perform rites at every bridge along the way to the burial ground.

Mr Lee (the gentleman in yellow boots seen in the first photo) told me that the coffins and remains had disintegrated and had merged with the soil. Not surprising, given that they had passed about 70 years ago. The gravediggers gathered some earth and put it in plastic bags for the purposes of cremation.

I was curious to know how the gravediggers knew that they had dug deep enough to reach the remains. Mr Lee explained that the gravediggers would know once they reached a flat surface as this was the bottom of the coffin.

The gravediggers were also able to tell that my aunt died when she was a child. If you look at my aunt’s grave, you can see a ‘step’ indicating that the coffin was shorter than an adult’s.

The grave of grandfather dug until a flat even surface was reached, where the coffin had been laid (photo Aylwin Tan)

I was worried that Dad would not be able to negotiate the uneven terrain to the grave sites but the path worn out by the gravediggers proved manageable. Mr Lee told me that these gravediggers are the last of their kind in Singapore.

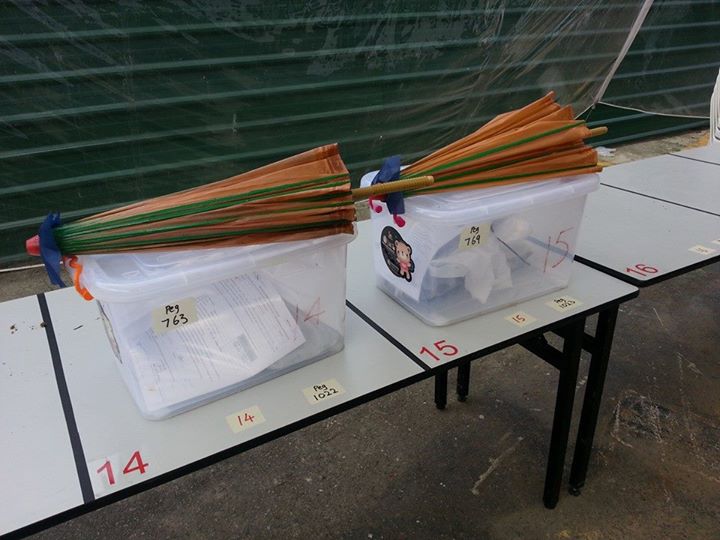

Dad spent some time telling his story to the gravediggers while I sorted out with Mr Lee the items found in the graves. Dad’s chair was provided by Swee Hong, the company that won the exhumation tender, a testimony to their planning and attention to detail. Also, you can see how they used the umbrellas to shield the boxes from the sun.

Umbrellas shading the remains from the sun as required by traditional practices. Aylwin’s father (seated) chatting with the grave diggers (photo Aylwin Tan)

The gravediggers recovered a chain and part of a bowl from my aunt’s grave. The bowl was probably used in the funeral rites. Mr Lee asked if I would donate them for research. I shall have to ask my elders’ permission first.

My grandpa’s grave yielded a bullet and a piece of metal which looked like a cone with the top portion cut off. I had to surrender the bullet as it was not a spent round. The gravediggers surmised that the metal piece came from the bomb but I wonder where the bullet came from. Dad said that the metal piece was not the cause of grandpa’s death; a beam had fallen on grandpa’s head and cracked it open. Death was instantaneous. The sight must have been extremely traumatic for the family. Dad was only 11 or 12 then.

One unexpected development came about when Dad suddenly said that my great grandfather was also buried somewhere in Bukit Brown. Dad did not know his name or the location of the grave site. Apparently, only one of grandpa’s brothers had this information and he had since passed. According to Mr Lee, great grandpa’s remains will be exhumed and disposed of if unclaimed after a period. Mr Lee also said that there was still hope if someone in my family could remember great grandpa’s name as the tombstone would surely state grandpa’s name. I’ll try my best to ask my relatives but am not very hopeful.

I will miss the 2 “Yodas” guarding grandpa’s grave. The other 2 guards look kind of effeminate.

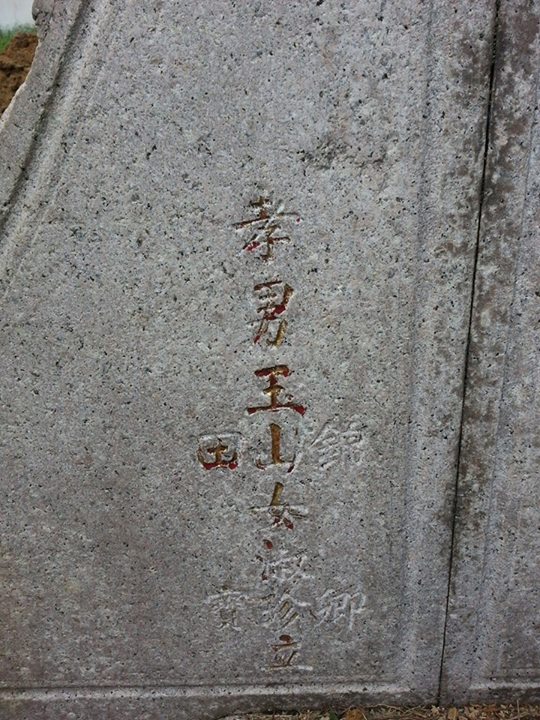

The left panel of the tombstone lists grandpa’s sons and daughters. Dad is ‘Geok San‘, which means ‘jade mountain’ in Chinese. In accordance with Chinese tradition, the sons and male cousins in the same generation have the same identifying name. In my Dad’s generation, the name is ‘Geok‘. In mine, it is ‘Wee’, which means ‘great‘ in Chinese. I understand that these names are predetermined by the Chinese Almanac.

The exhumation ended on a quiet note. After I had given written confirmation of the items from the graves that I had retained, I was given printed photographs of the two grave sites and that was it.

I was very impressed with the professionalism of the Swee Hong staff. They were attentive to my requests and sensitive to religious aspects of the exhumation. They worked fast but were in no hurry, allowing claimants all the time they needed to carry out their religious observances. Thanks to them, the exhumation process went smoothly.

– Aylwin Tan-

Additional Information : Both grandfather and aunt died on 18 Jan 1942.

Grave of Tan Cheng Moh 陳青茂 #769 (photo credit The Bukit Brown Cemetery Documentation Project )

Grave of Tan Siok Hwa 陳淑華 #763 (photo credit The Bukit Brown Cemetery Documentation Project)

Editor’s note: We would like to thank Aylwin Tan for giving us permission to reproduce his personal account on the blog. If you are a descendant who has ancestors staked for exhumation, please share your story with us.

Email us: a.t.bukitbrown@gmail.com

by Sugen Ramiah

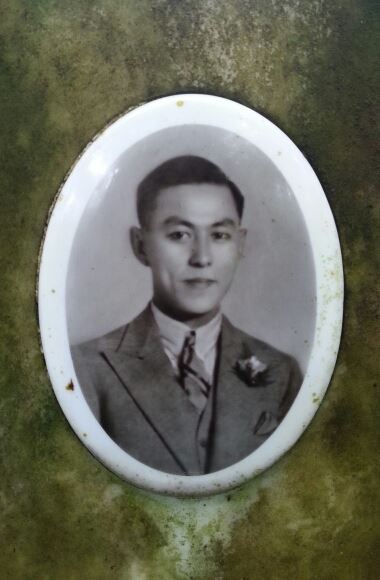

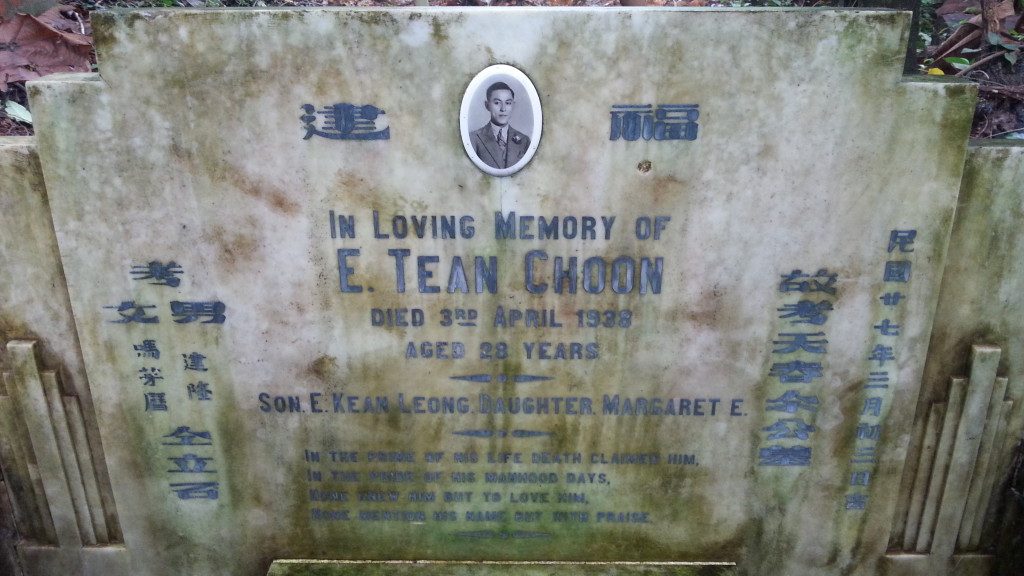

While exploring Hill 4, I stumbled upon a tomb of a young man, by the name of Ee Tean Choon.(E Tean Choon on tombstone)

It was very unique because the tomb was of a modern design in marble. And so I started a little research on his family in early November 2013. It was on the 31st of December 2013, while strolling with brownies Peter and Ee Hoon, that I was told that there was another art deco tomb, similar to that of Ee Tean Choon that also belonged to the Ee family, his grandparents. Here’s what I have traced of the Ee Tean Choon family tree.

Grandparents: Ee Swee Hin and Khoo Swee Yee

Ee Swee Hin passed away on the 8th September 1942 and his wife Khoo Swee Yee, on the 19th February 1955. They are buried together in Hill 5 Division B with LTA tag #1122 and will be exhumed in March.

Father: Ee Yean Keat

Ee Yean Keat was the eldest son of Ee Swee Hin and Khoo Swee Yee. He had two other siblings, Ee Yean Bee and another adopted brother – Tan Eng Yam. Born in Malacca in the year 1884, he was educated in a high school there and came to Singapore to look for a better future. He married Seow Joo Neo and had seven children. He first started work with Netherlands Trading Society in 1904. After 6 years, in 1910, he worked as a cashier with the KPM shipping company. He wanted an early retirement after 25 years with the shipping company. However, he later joined the Straits Times Press (Malaya) Ltd and officially retired in 1959 at the age of 75. He was also known as the “Grand Old Man’ of the accounts section of Straits Times Press (Malaya). He passed away on the 24th of September 1968 at the age of 84. The Obituary section in the archives indicates that he left behind 2 wives. Seow Joo Neo the mother of Ee Tean Choon, passed away on the 4th of January 1985 at the age of 102. She left behind 19 grandchildren and 16 great grandchildren. No information has been uncovered about Ee Yean Keat’s other wife.

Ee Tean Choon (E Tean Choon on tombstone)

Ee Tean Choon born in the year 1910 and was the first born of Ee Yean Keat and Seow Joo Neo of No.350 East Coast Road. He was the eldest of seven children. He married Ruby Chia Boey Neo , the fifth daughter of Mr & Mrs Chia Keng Chin of No.8 Saint Thomas Walk, on the 3rd of October 1936. Chia Boey Neo the grand-daughter of Mr Chia Hood Theam, was born in July 1914 and was 22 years old when she married Ee. They didn’t have their own children but adopted two babies -Willie Ee Kean Leong and Margaret Ee.

Sadly, Ee Tean Choon died of typhoid, on the 3rd of April 1938, at just 28 years old. He left behind a young widow and two infants, barely two years after his marriage. The two infants were then adopted by his brother, Ee Tean Cheng and the young widow returned to her parents’ house.

Inscribed on the tomb is an epitaph :

‘In the prime of his life death claimed him, In the pride of his manhood days, none knew him but to love him, None mention his name but with praise.’

I believe that the epitaph was taken from ‘The life of Rev. William James Hall, M. D.: Medical Missionary on the slums of New York, Pioneer Missionary to Pyong Yang, Korea’ 1897. It is about how Rev Hall ministered to the sick and wounded of Korea and his martyrdom. Coincidentally, both William (Willie for short) Willie and Margaret, were the names of Dr. Hall’s great grandparents.

Ee Tean Choon is buried in Hill 4 Division C with LTA tag #2612. He has been claimed by the family of his wife, the late Mdm Chia Boey Neo.

Brother : Ee Tean Cheng

Ee Tean Cheng was actively involved in many athletic associations such as the Useful Lads Badminton Party, Horlicks Badminton Party and was elected as vice president of the S.A.S.U (Singapore Armature Sports Union) in 1940. The tournaments, training and meetings were often held in the badminton court of the Ee’s residence at East Coast Road. He worked for Ford Motors and married to Ong Lian Neo Nellie on the 15th December 1940. Unfortunately, she passed away on the 26th October 1941 while in labour, both mother and child didn’t survive. She was buried in Bukit Brown and Raymond Goh has a blog post on her life here

Ee Tean Cheng had a second marriage to Lily Oon Siok Neo. They had a son, Winston Ee Kean Leng and also adopted the late Ee Tean Choon’s children – Willie and Margaret. He had five grandchildren. He passed away on 3rd April 1999, coincidentally the anniversary of his brother, Ee Tean Choon ( 3rd April 1938)

Brother: Ee Tean Chye

Colonel Ee Tean Chye was the first Commander of the Singapore Air Defence Command and in 1972, the first Chief of Air Force of the Republic of Singapore Air Force. He has three children, Patricia Ee, Laura Ee and Christopher Ee.

Son: Willie Ee Kean Leong

Willie Ee Kean Leong was the director of Sankyo Seiki Singapore Pte Ltd. He married Lim Eng Hong, eldest daughter of Mr Lim Kim San, former cabinet minister and first chairman of HDB. They had two children, Ee Kuo Ren and Ee Yuen Ling.

Daughter: Margaret Ee

Margaret Ee married Mr Richard Png and had two children, Dr Kenneth Png and Keith Png.

Postscript : Unfortunately both grandparents and grandson will be moving house to make way for the new highway. However both grandparents and grandson will be interned in the same block in Choa Chu Kang Columbarium. This is just another story of another ordinary family that has contributed to this country. May they rest in Peace.

Offerings for Ee Tean Choon on the day of the Winter Solstice 21 December 2013, prepared by brownies Choo Ai Loon and Sugen Ramiah (photo Sugen Ramiah)

Sugen Ramiah is a teacher by training and his interest includes observing and documenting Chinese festivals and rituals conducted by temples. This is his first foray into researching family trees.

Read his blog posts on Salvation for Lost Souls here and here

References for Ee Family

The life of Rev. William James Hall, M. D. : medical missionary to the slums of New York, pioneer missionary to Pyong Yang, 1897. (E-book) Emmanuel College Library, Victoria University

Announcement. (1936, June 23). The Straits Times

Tean Cheng-Ong. (1940, December 16). The Singapore Free Press and the Mercantile Advertiser

Deaths. (1941, October 26). The Straits Times

Cashier, 75, Retires for Second Time. (1959, December 31). The Singapore Free Press

Deaths. (1968, September 25). The Straits Times

Deaths. (1985, January 5). The Straits Times

Condolences. (1994, September 4). The Straits Times

Deaths. (1999, April 4). The Straits Times

Deaths. (2000, June 20). The Straits Times

The Air Force, Singapore : Republic of Singapore Air Force, 1988

Controlled Growth Restriction Policies For Certain Closed Food-Chain Systems by Patricia G. M. Ee 1992. Simon Fraser University, April 1992.

Pre- exhumation rituals for the nearly 4,000 pioneers who will have to be exhumed to make way for the highway, took place on the morning of Thursday, 28th November. A short and simple ceremony, it was organised by the Land Transport Authority and Swee Hong construction company for descendants. More than 500 descendants together with well wishers and brownies were in attendance.

The rituals were conducted by 7 members of the Inter Religious Organisation.

Prayers were offered for the peaceful move of the soon to be exhumed pioneers to their new homes and for the safety of the people who will be working on the site.

The descendants who arrived were confronted by a new almost “fortress-like” Bukit Brown where barriers had been put up in preparation for exhumations, scheduled to begin in December 2013

The area for the ritual prayers was under a marquee enclosed by a metal barrier and restricted to descendants. Registration was required.

The area within was quickly filled to capacity

It quickly became standing room only

The scheduled time to begin the prayers was 10am. It was delayed because of the unexpected crowds and started about 15 minutes later.

Religious leaders from left to right represented: Jainism , Buddhism , Taoism , Hinduism , Christianity, Sikhism and Baha’i faith (photo below)

The religious leaders took their turns to pray starting with Jain leader in pink, followed by Buddhist leader. (photo below)

The Taoist leader (in black robes) was followed by the Hindu religious leader

The prayers took about 10 minutes and the ceremony was over. A few descendants took the opportunity to also pay their last respects personally to their ancestors and came bearing offerings.

Victor Lim, a brownie offered his own prayers of remembrance and respect to the earth deity at the Lorong Halwa gates. Bukit Brown to him is a place to remember his ancestors and affectionately as he is always wont to say “my playground”

Victor Lim : “I don’t know when we can meet again. Since the past 1 1/2 years, we have been meeting with those lonely souls every week. This morning we are departing from this endless, from a party that needs to be dispersed. Alas, we would still need to leave and this brings me good memory. I wish you all the best, bless you peace when you leave, and may this good luck come forth to your new home. We will think of you now and then, and we will be together , not forgetting the milestones of our social memories and roots.”

And finally, all the way from London, Sugen Ramiah remembers Bukit Brown in his prayers at the Westminster Cathedral. His message : While Rev Fr Paul Staes said a prayer for the dead in Bukit Brown, I too lit up a candle and said a prayer for the dead in the Chapel of Holy Souls.

Eternal rest

grant unto them O Lord,

may perpetual light

shine upon them;

May they rest in peace. Amen

Amen, indeed amen. A ceremony that seem all to short, commemorates a farewell to those for whom Bukit Brown has been home for decades. We wish you all a safe and peaceful passage to your new homes.

Read Walter Lim’s blog on the rituals in Chinese here

A postscript. Thursday, 28 November 2013, was also the day the Roundabout became a Road.

Follow the path of destruction here

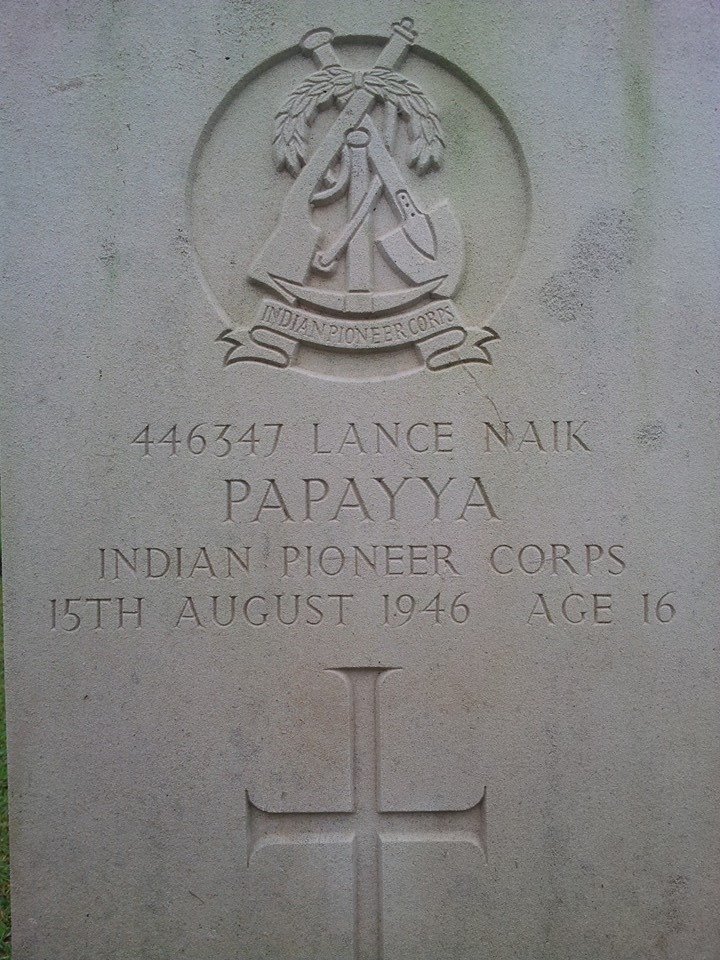

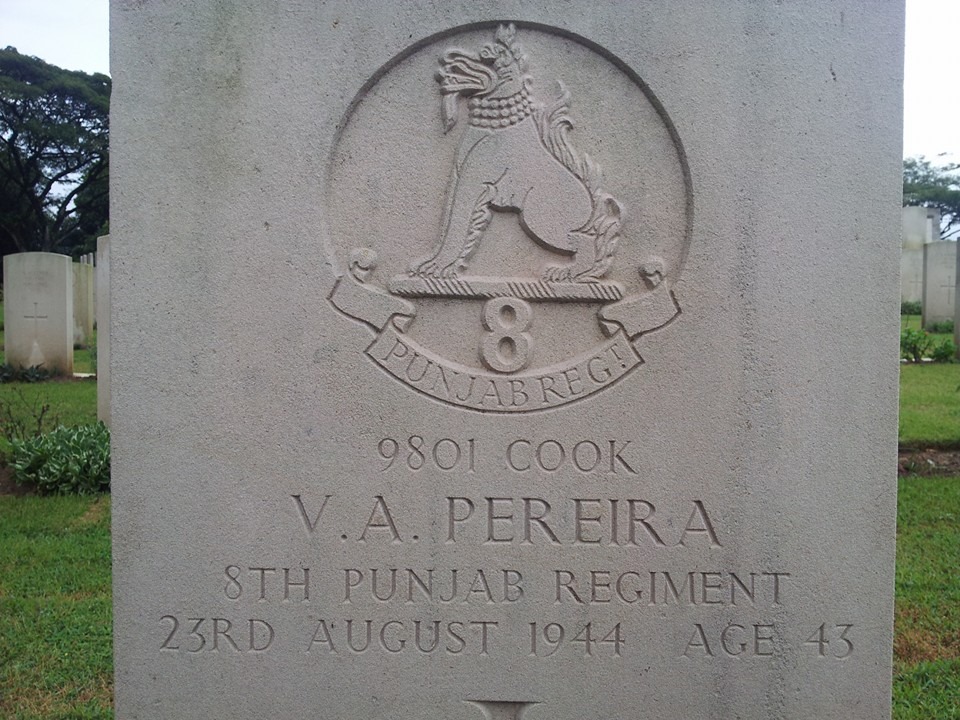

Dateline Sunday 10 November, Kranji War Memorial.

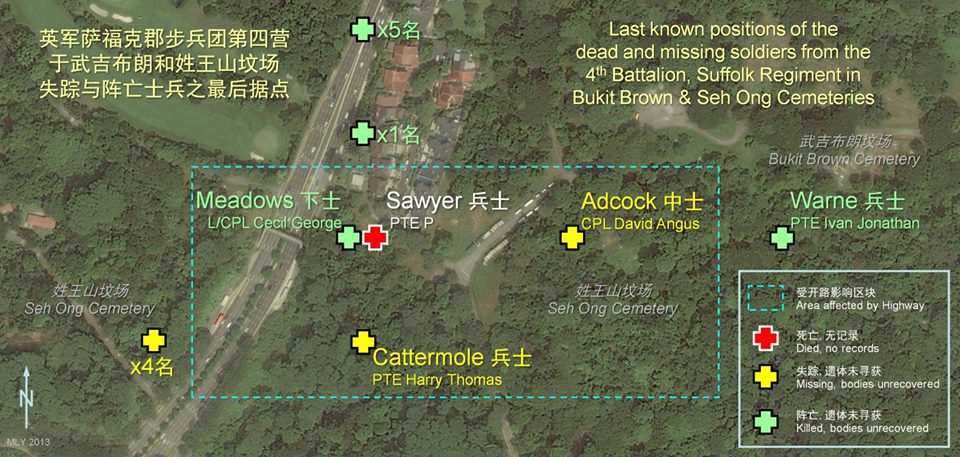

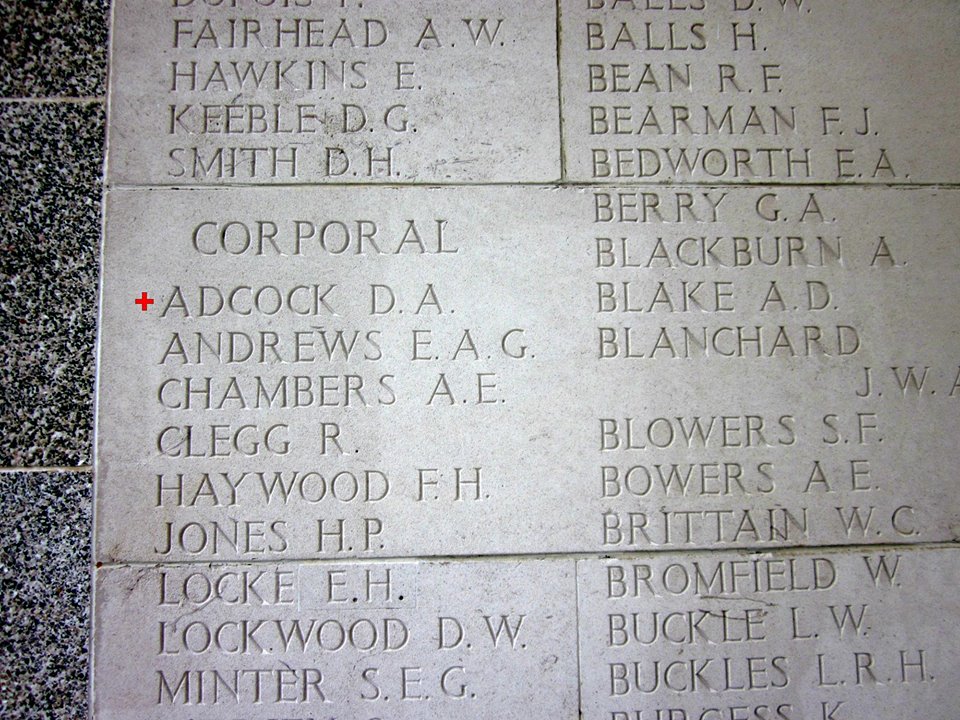

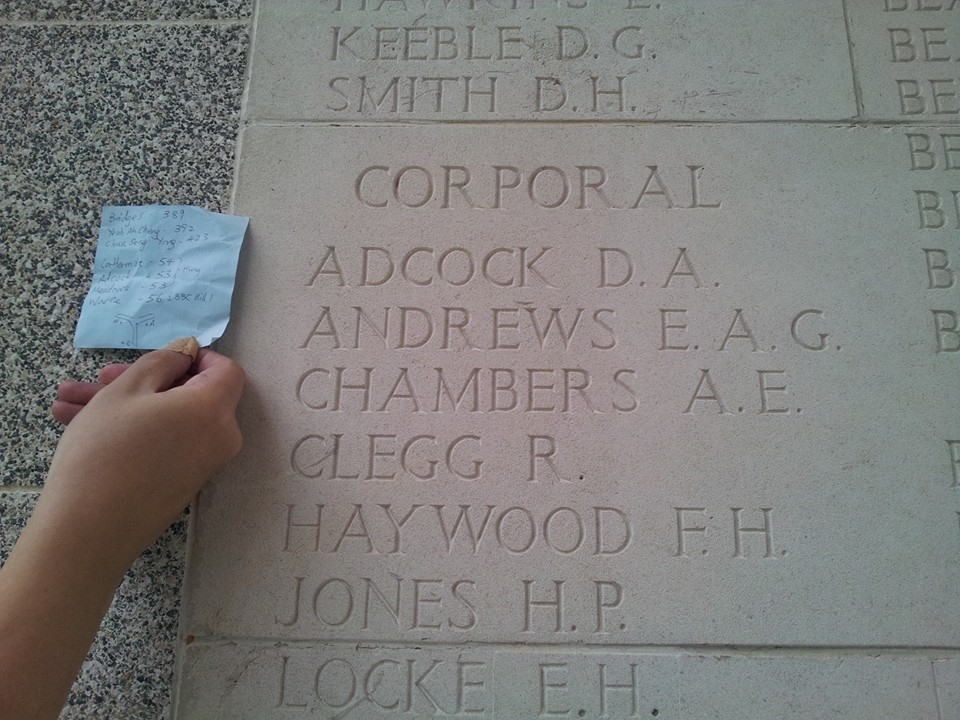

Remembrance Day was commemorated at the Kranji War Memorial in a ceremony dedicated to those who died fighting for Singapore during World War II. Brownies Khoo Ee Hoon and Mok Ly Yng who attended the memorial service had another mission when they were there, to seek out the names of 5 soldiers who had been listed as missing in the Battle at Cemetery Hill (Seh Ong and Bukit Brown Cemeteries).

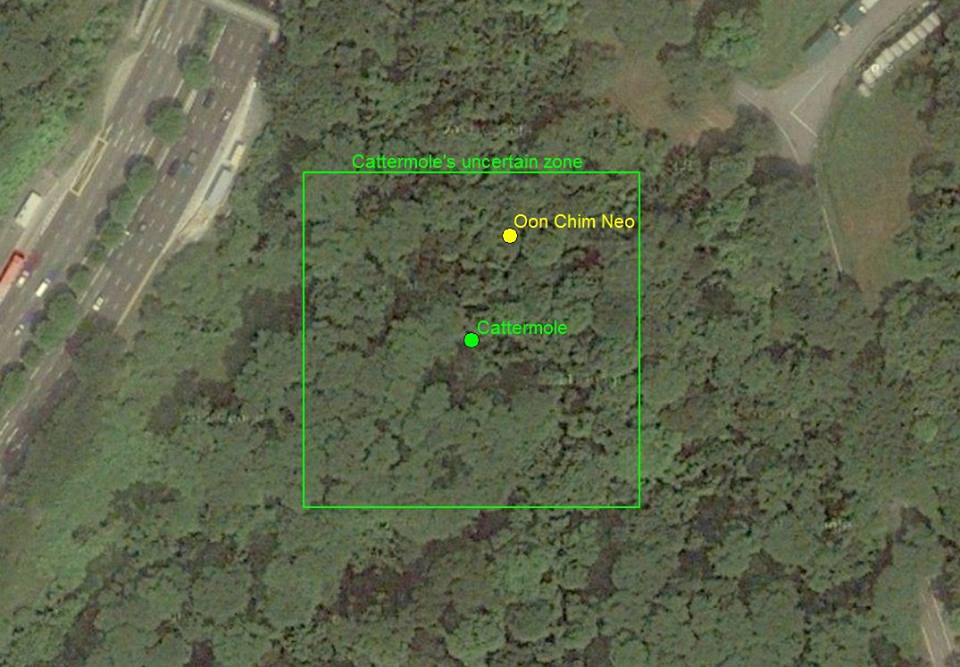

Based on war records, Ly Yng had already mapped out the dead and missing soldiers from the 4th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment, whose last known positions are right in the middle of the proposed 8-lane highway cutting across Seh Ong and Bukit Brown Cemeteries.

The 5 soldiers, named are not the only ones fallen in the battle.

“4x in yellow to the left of the green box represents 4 individuals known to be buried at that position. At the top of the bo along Lornie Road are know to be 5 soldiers (5x), as with the 1x (in green) at the Lornie Road houses. As these soldiers were located outside of the immediate threatened area, I did not include their names, so as to reduce map clutter.But I decided to keep them in the map to provide some context and indicate that there are in fact more soldiers around the area within the Greater BB area.” Mok Ly Yng.

At the Kranji War Memorial, the soldiers’ names on the memorial wall :

Corporal Davis Angus Adcock

Singapore Memorial Column 53, Kranji War Memorial

Missing: 12 Feb 1942

Lance Corporal Cecil George Meadows

Singapore Memorial Column 53, Kranji War Memorial

Killed: 14 Feb 1942

———-

Private Harry Thomas Cattermole

Singapore Memorial Column 54, Kranji War Memorial

Missing: 14 Feb 1942

Missing. Last seen on Hill 95, badly wounded on 14 Feb 1942.

Mok Ly Yng clarification of Cattermole’s position: “Due to the large map coordinate error, Cattermole could be buried within 50 m of the map coordinate’s position. in other words, he could be very, very to Oon Chim Neo’s grave too. In fact the uncertainty area overlaps her grave. “

Private Ivan Jonathan Warne

Singapore Memorial Column 56, Kranji War Memorial

Killed: 14 Feb 1942

Buried top of Highest hill Chinese Cemetery East of Adam Road in Adam Road – Lornie Road Area by padre Polain 2/26 Bn AIF 14.2.42 (crossed out May 1942) Effects 2 Identity Discs, 1 cross.

Private Ivan Jonathan Warne’s position is not affected by the road construction. He is listed as the only known unrecovered casualty to be buried in Bukit Brown Municipal Cemetery proper (Hill 1).

Mok Ly Yng on the case of Private P Sawyer in the map:

“The 5 named individuals on the map were known to have been killed or last seen at those map coordinates just before or after the surrender. But after the war, those who were recorded as’ buried’ could *not* be found again and their remains are still missing. Private P Sawyer is the most difficult to find. His records showed that he had ‘Died in Singapore’ on 14 Feb 1942 and that he was buried on 17 Feb 1942 but this burial record was crossed out at a later unknown date. This leaves him with no records and hence he does not appear on the Singapore Memorial at Kranji nor the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s (CWGC) database or nominal roll, unlike the other 4 named soldiers presented here.”

In battle, the Cambridgeshire Regiment and the Suffolk Regiment fought in adjacent sectors. The Cambridgeshire Regiment held the Adam Park area while the Suffolk Regiment the Bukit Brown Cemetery area. In death, casualties of the two regiments are buried in adjacent sections at Kranji. This photo shows the boundary between the Cambridgeshire Regiment and the Suffolk Regiment in Kranji.

Kranji War Memorial Sunday 10 November, 2013. Cambridgeshire and Suffolk regiments (photo Mok My Yng)

From Jon Cooper. historian and war archeologist on the Adam Park Project, who also conducts the Battlefield Tour at Cemetery Hill once at month at Bukit Brown:

‘The fate of the missing Suffolks on Bukit Brown is just part of the rich WW2 heritage that can be found on the hills. There were many other units fighting in the area, constantly passing over the cemetery during the ebb and flow of warfare. It is most likely that there are more missing men to be found amongst the headstones.

There will also undoubtedly be spent ammunition and equipment to be found across the site, the remnants of fieldworks and bomb craters and the general detritus of war. Each item will be the part of a big jigsaw of artifacts and by plotting the locations in the landscape it will be possible to gather invaluable information about fighting that took place there.

The impending work on the hills will peel back the top layers and will undoubtedly expose these traces of the past.Hopefully the construction teams, with proper instruction will identify these clues and call in the experts to catalog and retrieve the material before the concrete is poured over it. There is a chance; just one chance to collect this invaluable evidence.

But most of all there is the possibility that we may come across the remains of our missing men. A chance to identify them and lay them to peaceful rest amongst their own. The fact that we go to great lengths to retrieve these men says as much perhaps about the attitude of Singaporeans today as it does about their generation of sacrifice.’

Jon Cooper and Mok Ly Yng who are working together to identify locations of the fallen Suffolk soldiers (photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

Mok Ly Yng at the memorial wall looking for the names of the fallen in the Battle on Cemetery Hill ( photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

The Suffolk Regiment casualties list on the Singapore Memorial at the Kranji War Memorial, columns 53 & 54. (photo Mok Ly Yng)

Mok Ly Yng is part of the documentation team tasked by the government to record and document graves affected by the impending highway

The Kranji War Memorial is dedicated to the men and women from United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Sri Lanka, India, Malaya, the Netherlands and New Zealand who died defending Singapore and Malaya against the invading Japanese forces during World War II, it comprises the War Graves, the Memorial Walls, the State Cemetery, and the Military Graves.

Kranji War Memorial, Sunday 10 November 2013. A member of the Royal Air Force, which is Jon Cooper’s unit (photo Mok Ly Yng)

Kranji War Memorial, Sunday 10, November 2013. A member of the Royal Engineers, the unit responsible for mapping and map production (photo Mok Ly Yng)

Ubique Quo Fas Et Gloria Ducunt

Everywhere – Where Right and Glory Lead

This is a blog post that will be updated as the destruction continues……

Thursday 28 November ( Pre Exhumation Rituals) : The Roundabout has become a road

A reminder of what it once was, almost exactly a year back in December 2012 :

Friday 22 November

Wednesday 13 November , roundabout paved

Saturday, 9 November. Morning 9am, no works within the grounds.

Guided walks proceeded from the ‘ole rain tree. Respite!

Thursday, 7th November. The road works in progress

Paving the roundabout, and putting up hoardings along Adam Road.

Photos on Flicker on 7th November, 6pm here

Wednesday 6th November, other areas barricaded by concrete blocks

Wednesday 6th November, 2013 clearing continues at the roundabout

Tuesday 5th November, 2013. The roundabout is destroyed.

Friday, 11 October, 2013. The roundabout is barricaded and sealed

Before Oct 11, 2013. The Roundabout

Dateline 19 October 2013

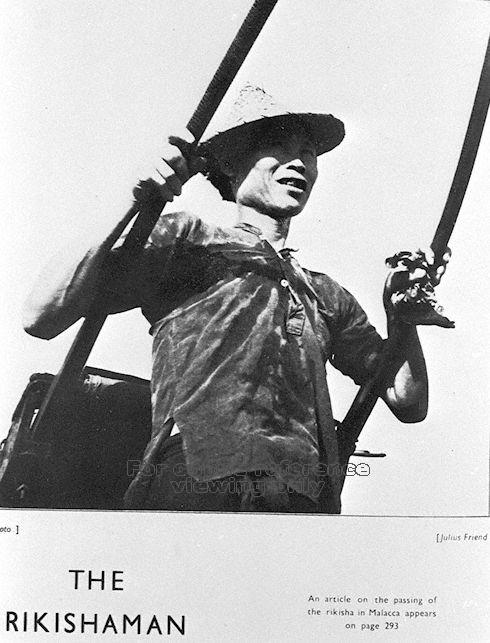

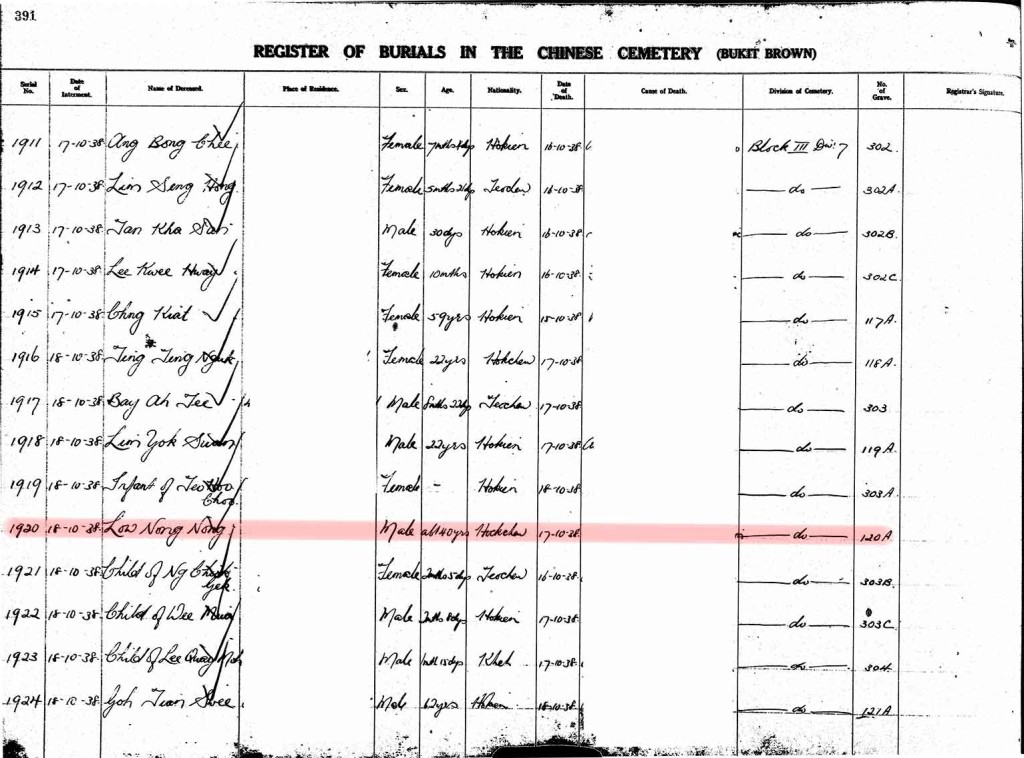

The Story of the Rickshaw Pullers Strike and a Man called Low Nong Nong

(compiled with research by Raymond Goh and a Pat Sg, a member of the Facebook Group -Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown Cemetery)

Today, Raymond Goh located the tomb of rickshaw puller Low Nong Nong who died during a confrontation between striking rickshaw pullers and the police. In the clash which occurred on 17th October 1938, Nong Nong lost his life, and there were no witnesses to his death.

The rickshaw pullers were striking for lower rents of their rickshaws from the owners.

“EXCERPT: {{{ Low Nong Nong was found dying from a fractured skull, face down on the side of the street emptied of his comrades. His death sent reverberations through the rickshaw districts, making pullers more determined than ever to force the owners to come to an agreement on their terms.”

“His funeral the same day was an unnerving, demonstrable display of strength and solidarity. Three thousand men solemnly followed the lorry bearing his coffin to BUKIT BROWN CEMETERY to a pauper’s grave, and, as the police anxiously stood by and watched, one of the longest funeral processions in Singapore’s recent history, stretching from Wajang Satu to Newton Circus, passed.” (Source: Rickshaw Coolie: A People’s History of Singapore, 1880-1940)

The community of rickshaw pullers saw Low Nong Nong as a martyr to their cause. On his tomb his epithet reads:

He died for the public, his death is as heavy as Taishan, tomb erected by his fellow rickshaw pullers

“Taishan” in this case is 泰山, Mt Tai, one of the sacred mountains of China. (from Jason Kuo)

Background to the rickshaw pullers strike : The Lot of the Coolie

Many rickshaw pullers had been on prolonged strike during that period (04 Oct – 15 Nov 1938), & thus had no earnings. Low Nong Nong himself died on 17 Oct 1938 — penniless & w/o any kin in Singapore.

The community of rickshaw pullers had been periodically unemployed from 1928 onwards & throughout the post-Depression 1930s. During this period, the colonial govt had been reducing the no. of rickshaw licenses so as to encourage the use of the motorcar.

In response, profit-seeking rickshaw fleet owners (the “siong thau”) took the opportunity to hike up the rental fees. Fleet owners also made rickshaw pullers contribute part of their earnings to the mandatory “China Relief Fund”, which purportedly assisted countrymen who were suffering “deep water and scorching fire” back in China.

Low Nong Nong was probably described as a martyr by his rickshaw brethren, because:-

Despite being hungry & desperately in need of money, he dutifully observed the rickshaw strike, as previously agreed upon amongst the pullers at the 小坡 (xiǎo pō, “Small Town”) area of town.

He lost his life while participating in a rescue group that had attempted to free a Hockchew rickshaw puller, who was arrested by the police during an earlier confrontation at around 11am on 17 Oct 1938.

Background on the incident : The Betrayal

The morning altercation had occurred because Low Ah Law, a Henghua puller, had unilaterally disregarded the rickshaw strike, & blatantly plied his rickshaw on the streets of 小坡 (“Small Town”) — ie. the side of Sg River where most of the rickshaw pullers were supportive of the ongoing rickshaw strike.

Subsequently, the Henghua puller was confronted & restrained by a “Hockchew crowd” of fellow rickshaw pullers at Victoria Street. The police intervened & one of the Hockchew pullers was consequently arrested.

The “rescue” clash between the Hockchew rickshaw pullers & the police occurred during the afternoon of the same day at the junction of Arab & Victoria Streets. Police reinforcements were deployed & “strong-arm measures” were used to subdue the angry “rescuers”.

It was in this clash that Low Nong Nong was found lying face-down & dying from a broken skull on a street that had been cleared out by the police.

In a sense, Low Nong Nong — who was already famished & simply getting by his day — died alone on a street at 小坡 (“Small Town”), because a fellow 小坡 & Foochow prefecture rickshaw puller had betrayed his brethren by not observing the strike.

Meanwhile, the 大坡 (“Big Town”) rickshaw pullers (including the majority Hokkiens) — who had refused to support the strike — merely looked the other way.

* Account of Low Nong Nong’s death on the afternoon of 17 Oct 1938 from ‘Rickshaw Coolie: A People’s History of Singapore, 1880-1940’ (James Francis Warren): http://goo.gl/E7PEif

EXCERPT: {{{ Unemployed, hungry, and desperately in need of money, [Hockchew puller Low Nong Nong] had visited Seah Toon Tan, a Hockchew friend, that morning. He borrowed a dollar from him and left his house in Geylang at about 9 am, without ever having discussed the strike.

The trouble leading up to his death began when a crowd attempted to restrain a Hengwah, Low Ah Law, who had ventured along Arab Street with his rickshaw. At the junction of Victoria Street he was assaulted by a Hockchew crowd.

Police had barely arrived in time to rescue Low Ah Law and arrest one of the assailants. At once, a new crowd of around 400 began to take shape to rescue the captured puller.

Some were armed with fighting sticks, rickshaw shafts, bottles and bricks, and among them was Low Nong Nong. A clash ensued with the police. Shouts of “pah, mata, pah” (“strike, police, strike”) rent the air, as the crowd of pullers slowly closed in, injuring several constables with wooden clogs, poles and stones they hurled at them.

The situation was desperate with police injured and rickshaws wrecked all over the adjacent streets, until reinforcements arrived. Strong-arm measures were used to control and eventually disperse the crowd. Low Nong Nong was found dying from a fractured skull, face down on the side of the street emptied of his comrades. }}}

books.google.com.sg

Low Nong Nong can be found in blk 3, Div 7, no. 120A @ the pauper’s section (on a hillock about 200 meters from the tombkeepers shed at the foot of Ong Sam Leong family cluster)

s

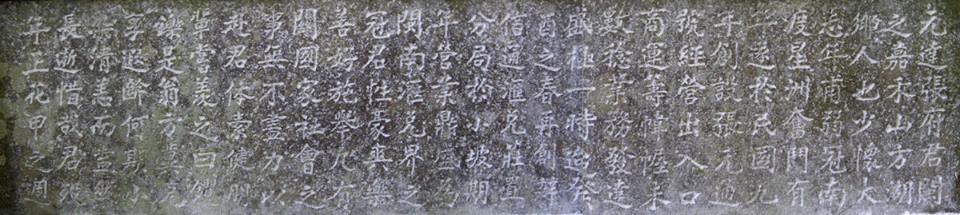

Located by the roundabout in Hill 1 (near the LTA signboard) is the tomb of Thio (Teo) Guan Tat who came from Fujian Province and was a pioneer in the remittance business.

On the altar of his tomb, is an epitaph inscribed in elegant calligraphy

Summarised by Brownie Khoo Ee Hoon:

“Mr Thio Guan Tat came to Singapore as a youth with high aspirations and who strived for many years before succeeding. Finally in 1920 he started “Thio Guan Tong” a import and export business. He profited from his business and shortly after started a remittance agency at South Bridge Road. His remittance business became the most well known and popular Hokkien Remittance company.

Mr Thio is a generous and kind man, who lend a hand to his fellow clan men and society.”

Thio’s tomb stake number 1044 will have to be exhumed to make way for the highway

Recent Comments