Alex Lim’s Story Part II

On the 2nd April 2012, Alex Lim and his family observed Qing Ming at Bukit Brown starting with his grandmother’s tomb, Tan Tee Teo which was accessed from Lornie Road. Part II continues as the family proceeded into Bukit Brown proper, to Hill 4 where they paid their respects to Lim Kee Tong and his wife, the paternal great great grandparents to Alex and his brothers.

Lim Kee Tong was a Singapore pioneer businessman and philanthropist who contributed to free education, to the Lam Ann clan and was a trustee of an award winning temple. As Alex goes through the rites of tomb sweeping, he recounts to the documentation team, led by Dr Hui Yew Foong and bukitbrown.com, what he has been told, heard and followed up on the life and times of his illustrious ancestor – a narrative that continues to unfold.

A closer look at the tomb of Lee Kee Tong and his wife and what it tells us

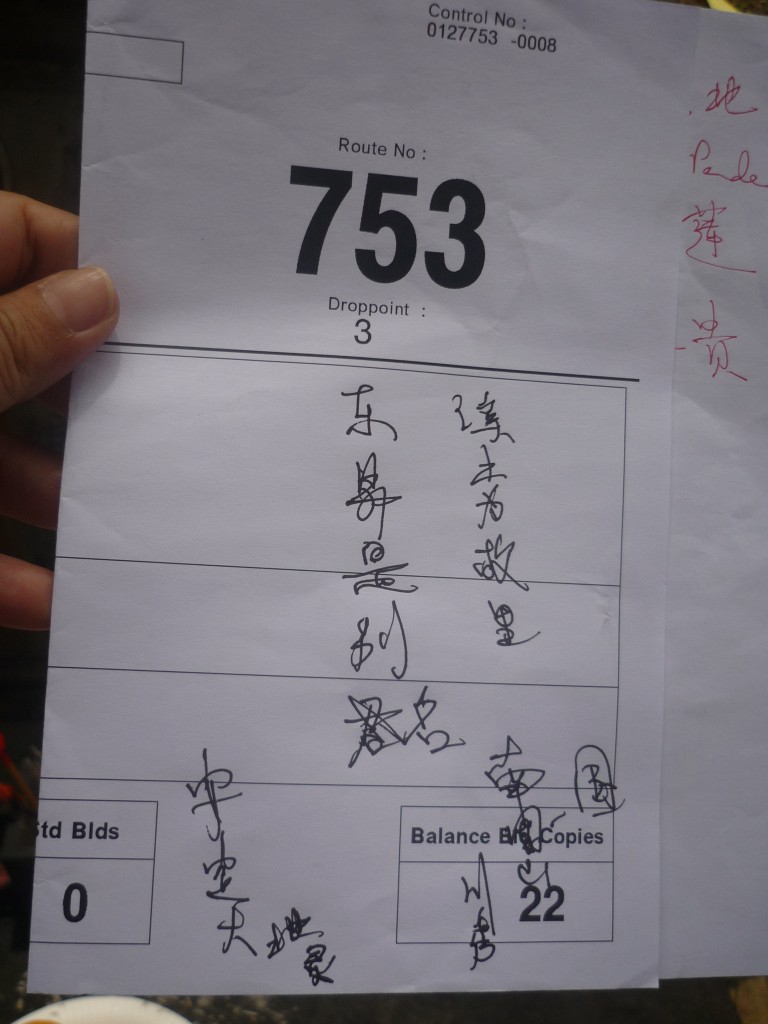

Couplets Translated by Ang Yik Han

The couplets, on the headstone, are based on his name 箕當:

箕裘克紹傳家有仁風

Following in his father’s footsteps, his benevolence passes down through the generations;

當義勇为遺德留千古

Always ready to answer the righteous call, his virtue remains for eternity

The couplets on the pillars are 溪東, 東昇 is my GGGF’s 號 -Pseudonyms or aliases (from Alex Lim)

南國山川秀

安宅大地靈

溪土為故里

東昇是別名

“The southern land has fine hills and rivers

With the earth’s auras it is a good place to build a tomb

Xi (Dong) is my hometown;

Dong Sheng is my other name”

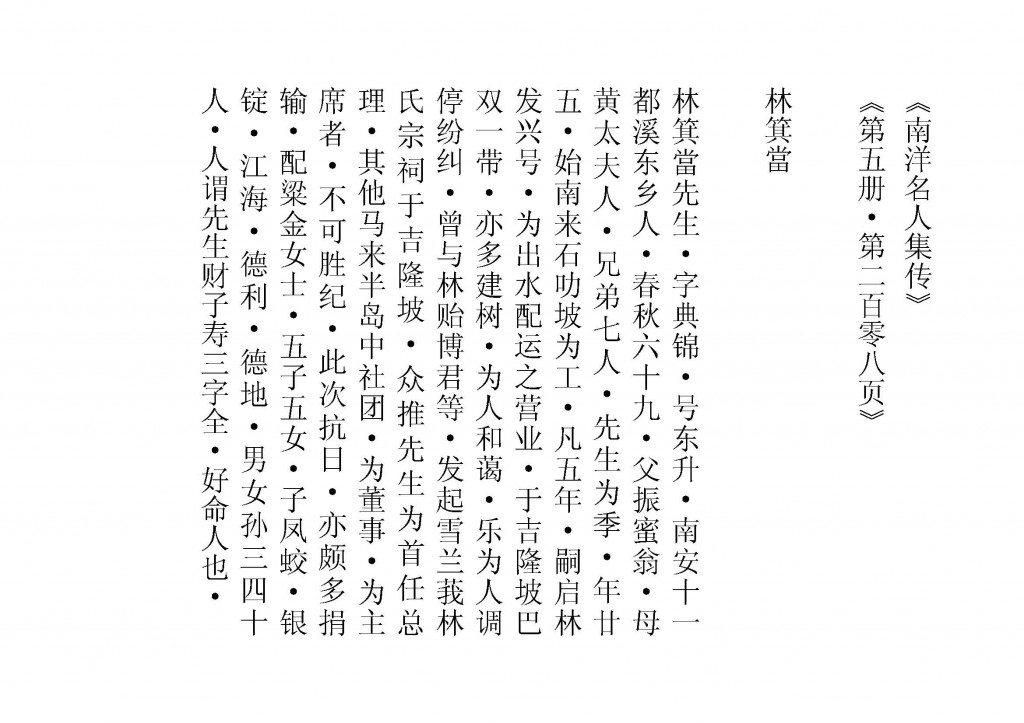

About Lim Kee Tong :

Lim Kee Tong was on the Board of Directors which rebuilt the Hong San See at Mohamed Sultan Road in 1913 .His name is inscribed on the granite pillars at the temple’s front, a distinction given only to those who played a major role in its construction. In addition, he was one of the founders and chairman of a school based in the temple’s premises which provided basic education to poor children from the neighbourhood. Subsequently, he was also appointed as a trustee of the temple.

Apart from Singapore, Lim Kee Tong was also active in Klang and Kuala Lumpur where he was one of the co-founders of the Selangor Lim Clan Association as well as its first chairman. His name can also be found amongst the contributors to the Lim (Lam Ann) Clan Family Self-Management Association in Cantonment Road, the umbrella body for the Lim clan in Singapore. He was active in many other community groups and often gave generously to public and charitable causes such as famine and war relief funds.

Lim Kee Tong’s business interests:

“The trading company name was called Lim Huat Hin 林發興 and it was mainly active in Kuala Lumpur, Selangor & S’pore. Business routes included Indonesia, Philippines & China. My the second generation which ran the family business included my great grandfather and one or two my great granduncles who had their final resting places in Indonesia & Philippines. Exact locations unknown. My father said before that GGGfather, was also a landlord with 13 ~ 17 shop houses @ Hong Lim Pa Sat (Covent Garden).” Alex Lim

Closing shots of Qing Ming at Bukit Brown for the Lim’s on 2 April 2012

One for the family album for brother Roger, who could not be there for Qing Ming (photo Catherine Lim)

Alex’s Story Part 1

Compiled by Catherine Lim

In 1940, when Lim Sian Chin was only 6 months old, his mother passed away from a mysterious illness. Tan Tee Teo 陳甜桃; was only 23 years old.

On 2nd April, 2012, exactly 72 years to the date of Tan’s death (according to the lunar calendar) Lim Sian Chin, with his wife Hai Lian and 2 sons, Alex and Yong Beng paid what could be their last Qing Ming respects to her. (Roger, the middle son of Lim’s was in Dubai) Staked grave 3716 is one of nearly 4000 graves which lie in the way of an 8 lane highway that the government plans to build that will slice Bukit Brown Cemetery into half.

This is the photo essay of the Lims’ Qing Ming 2012 which was also covered by the documentation team led by Hui Yew Foong. It is composed from the view point of the eldest son, Alex.

” I remember back then when I was this nigh high, playing here among the lallang and the mozzies are still here ….” (photo Catherine Lim)

The Lim family were Taoist practitioners. In recent years, they have become Buddhists, as father believes after a period of time, the departed are already well and truly reincarnated. So offerings are “symbolic”

A unique way of wedging coloured paper through grass stalks so it won’t fly away (photo Catherine Lim)

This tradition comes from a Han emperor who after a long stint away from at war , returned home to pay respects to his parents. Their graves had become overgrown. So he decided to throw paper in 5 cardinal directions and where they landed and stayed, that would be where their graves were. A stone was used to wedge the paper to their tomb stones (that is why you still see stones on top of tombstones, it shows descendents have paid a visit.) Alex has his own unique way of “marking” the spot.

Post Script to Tan Tee Neo : The widower of Tan Tee Neo was to later marry her much younger sister sometime during or after World War 2. It was a fruitful union which resulted in half siblings for Lim and that branch of the family too continue to honour their late aunt at Qing Ming.

Alex’s story continues in Part II coming up soon where he pays his respect to his great great grandparents who are also buried in Bukit Brown. They are Lim Kee Tong 林箕當, Neo Kim 梁金. Find out more about the part Lim Kee Tong played in the setting up of a free school and a temple.

饮水思源 Remember The Source of the Water

Elizabeth Ong and Emma Lim

By Catherine Lim

In 2002 in London and Scotland, two Singapore couples stationed in the United Kingdom, welcomed new arrivals, both girls. Born four months apart, the Ongs in London named their daughter Elizabeth and she was their second child. The Lims in Scotland named their daughter, Emma and she was their first born

In 2006, after 13 years abroad, the Ongs returned home to Singapore because they felt it was time for their young family to root themselves to their country and they returned to the family home which with their children now houses 4 generations. Their children, elder brother Alexander to Elizabeth were enrolled in Nanyang Primary School and because they were still very young adapted well.

In 2010, the Lims after 12 years abroad returned home for very much the same reasons, to be with family and reconnect to their homeland. By then Emma had a brother and a sister. Their grandparents had visited them frequently when they were in Scotland and the grandchildren settled down comfortably in Singapore, all under one roof. Emma was able to enroll in Nanyang Primary School.

In 2011 Elizabeth and Emma met for the first time. They barely spoke in the first term of school but by term two their friendship just took off. Both are in the choir; Emma sings alto, and Elizabeth second soprano. Their passions are artistic. Dance lessons for Emma every weekend, and Elizabeth has been talking art lessons since 2007. Their mothers met and play dates were arranged whenever the girls had free moments in their busy schedules of school and extra curricula activities. But mostly the girls just text each other when apart.

As their friendship grew so did their mothers’. It was not long before they realised they had similar experiences of living abroad and coming home. When their husbands came into the picture, the Ong and Lim families found a deeper connection which reached back into Singapore’s past and found another friendship which their daughters’ echoed.

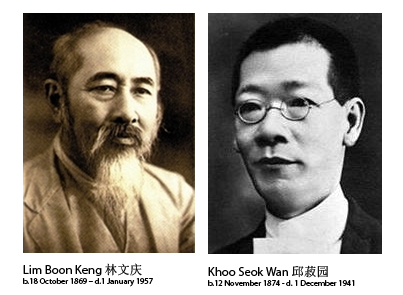

Elizabeth, is the great great granddaughter of Singapore pioneer and scholar Khoo Seok Wan and Emma is the great great great granddaughter of another luminous pioneer, Lim Boon Keng.

Lim Boon Keng and Khoo Seok Wan

By Ang Yik Han

One was the dapper son of a rich rice merchant from China, a poet and scholar who sat for the Imperial exams. The other was a local born Western trained doctor, recognised by government and society as one of the leading voices of the Straits Chinese community. Khoo Seok Wan and Lim Boon Keng made an unlikely pair of friends. But the historical and political milieu of their times gave birth to unlikely pairings.

Both men were supporters of the reformist movement in China which sought to re-vitalise the Qing Dynasty. Khoo founded the Thien Nan Shin Bao, a local Chinese newspaper sympathetic to the reformist cause; Lim Boon Keng was its English editor. Subsequently, Lim and his father-in-law took over another Chinese newspaper which also adopted the reformist line.

When Kang Youwei, the leader of the reformists, fled China after the Reform’s failure, Khoo offered him shelter in Singapore and sucour for the cause. With the threat of assassins dispatched by the Qing government hanging over Kang, Lim worked with Khoo and the Straits Settlements authorities to protect him. Kang moved three times during his short stay of five months in Singapore. The first two places were properties belonging to Khoo Seok Wan and the third hideout was none other than Lim Boon Keng’s house.

The two also combined their efforts in education and social reform. They established the Singapore Chinese Girls School with other progressive members of the Chinese community at a time when the proper place of women was at home and female education was look upon with disdain. Half of the funds for the school ($3000) were contributed by Khoo Seok Wan and both men served on the inaugural Board of the school.

Khoo’s role in society was greatly diminished in the years following his bankruptcy. He became destitute and had to scrap a living with his pen. Even then, the friendship continued.

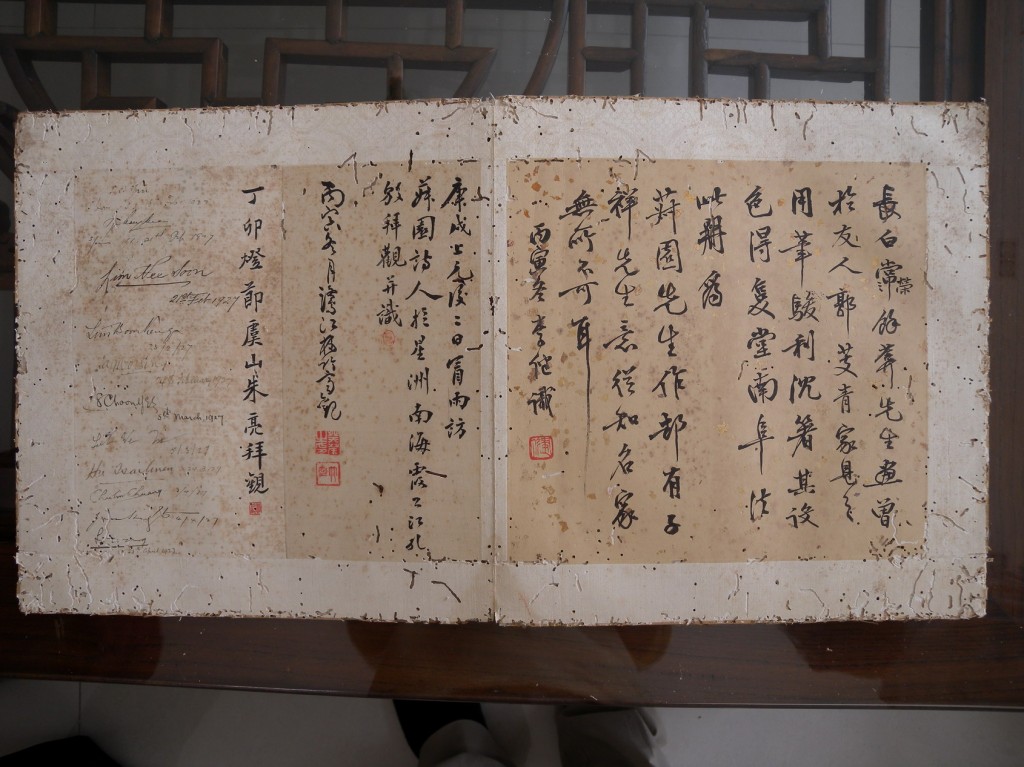

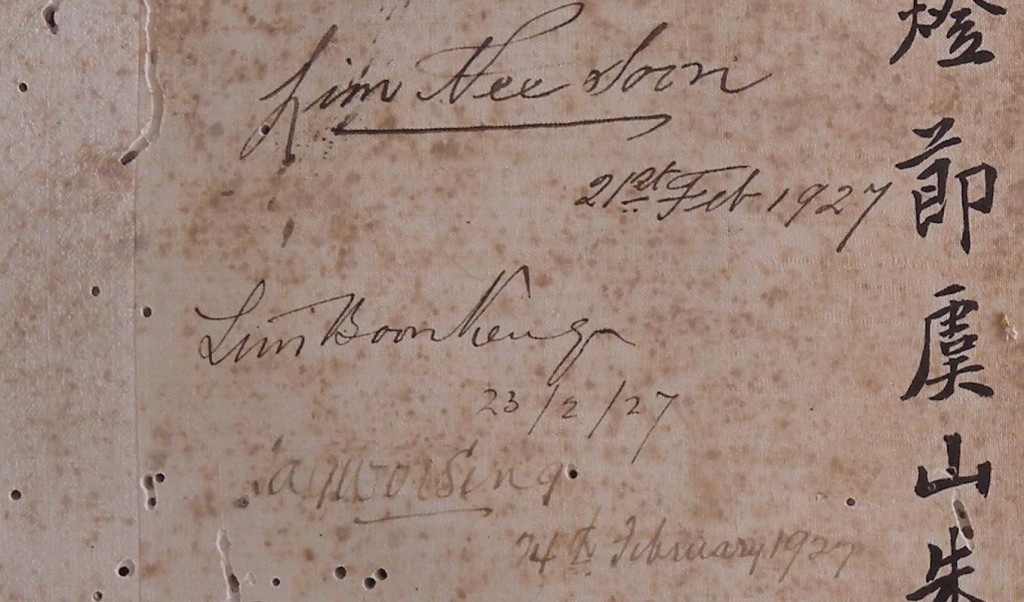

The Ong family has in their possession a book of calligraphy and original paintings which belonged to Khoo Seok Wan.

This book bears the signatures of various guests who had the honour of leafing through it, including Lim Boon Keng who visited in February 1927. By then, his full time job was the Chancellor of the Amoy University. Lim’s occasional trips back to Singapore were primarily for the never ending task of raising funds for the University, yet somehow he found time to visit his old friend. This signature is testimony to their enduring friendship.

Post script on Emma and Elizabeth

Emma on her friend, Elizabeth:

Elizabeth is pretty and cute.

Elizabeth is smart, funny and my BFF.

Elizabeth has a kind heart and always helps me when I am in need.

Elizabeth on her friend, Emma:

Emma is my BFF and she is fun and exciting to be with.

She always sticks by me through thick and thin.

Emma is pretty and she is a true friend to me.

The search for a long lost aunt buried at Bukit Brown began last year, when Miho Tan requested the help of Raymond and Charles Goh to locate his father’s sister. She provided these details

Name : Tan Lay Chee

Grave : C III, 857

Age : 18

Year of death : December 1932

Following up this year, Raymond found Miho’s aunt and from her tomb inscription discerned that Tan Lay Chee died at the young age of 17 on Christmas Day, 1932. She was unmarried, but a boy was inscribed in the tomb as a “stepson”. According to the information Raymond gathered – the burial registry does record cause of death – she died of mo tan, a kind of high fever.

He recalls her family visiting her tomb a few years ago but they had forgotten the route as the surrounds had become quite inaccessible due to fallen trees and overgrowth.

The family of Tan Lay Chee visited her soon after Raymond located her tomb, and brother Lay Chee connected once more with his elder sister.

Also buried at Bukit Brown, is Miho’s grandfather. Miho captured a family visit to his tomb in February in a video here

Grandfather Tan Choon Kiat was a book keeper and died at the relatively young age of 51 years old.

Miho’s grandmother, Lim Geok Yan survived her husband by more than 30 years. She died just past her 80th birthday and her ashes are interred at Bright Hill Temple at Sin Ming. Her grandfather’s tomb, is a double tomb but he rests alone. It can be deduced that his wife was originally intended to rest side by side with him.

The life and times of Lim Geok Yan is deeply etched in the mind of Miho’s father. He was the youngest of 8 children, 6 boys and 2 girls. We know she had to bury a child and as a young widow life must have been tough. Miho recalls what his father shared with him:

“Being a tough nonya my Dad says she had to pawn her jewellery bit by bit in order to maintain the household , the daily expense had to cover (they lived in a traditional Peranankan house), around 16 members which included 7 “cha bor kan” – Hokkien for maids. She was a strict mother too (Dad did not elaborate). I’m sure she would have been been a strict grandmother too and maybe I’ll be allowed to wear traditional Baba wear on special days.”

Miho remembers being taken to the Baba House, where her father pointed to a portrait of Lim Ho Puan hanging there, and he said to Miho, “there, that is your chor kong – (Hokkien for great grandfather)”

Lim Ho Puan is among a list of luminaries which include Lim Boon Keng, Lim Nee Soon and Lim Yew Hock named in the book Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, Business, Politics and Socio Economic Change, 1945 – 1967

A simple tomb of a long lost aunt, has become for the niece who never knew her, a touch stone revealing a family history which is both personal and historical.

Norman Cho Pays Tribute to Cho Kim Leong

– Norman Cho, 40 year-old Technical Officer (IT). A fifth generation Baba from my father’s paternal family and seventh from his maternal side. Presently, attempting to piece together my family genealogy.

“Ever since I was young, I have been curious about my paternal grandfather’s grave. We visited the graves of my materal (grandfather, great grandparents and great great grandparents). However, the family could not remember my paternal grandfather’s grave even though it is not that far back in time as my mother’s ancestors’ graves. I had never dreamed that I could finally find his grave if not for the Bukit Brown Cemetery Project. All that I knew was that he was buried in Bukit Brown. Finally, I can place a name to the grave that is my grandfather’s and be a dutiful grandson.”

The grave of my paternal grandfather, Cho Kim Leong, stood unmarked and forgotten for 6 and a half decades at Blk 4 Div A P584, Bukit Brown Cemetery. He died on 16 Dec 1945 at the age of 43 years and was buried on 18 Dec 1945. Cho Kim Leong, born in Malacca, was the son of Cho Poo, a Malaccan Peranakan pioneer of gambier, tapioca and rubber plantations in the late 1800s.

Grandfather was the only son of the third wife, Kong Moy Yean and grew up in the privileged millionaire’s row of Heeren Street, Malacca, unit no. 151. The family was known to have another unit which was at no, 84. I can imagine that the family was fairly well-off. He was the manager for his father’s rubber estate in Johore. (Click here for images of Heeren Street.)

His marriage to my grandmother Yeo Koon Neo in 1934 was his second, after the death of his first wife. When his mother died in 1935, grandfather inherited over 76 acres of the rubber estate. Then came World War II, the family fortune was ravaged and grandfather was forced to sell off his rubber estate just months before the war ended. He was consumed by depression over the loss of his property for worthless Japanese “banana money” and died soon after on 16 Dec 1945.

By then my grandmother, a widow with young sons in tow, aged 10 and 8, was too poor to afford to construct a proper tomb for him as bread-and-butter issues were of greater concern. Wealth and status is transient and change is the only constant both in life and in death.

Courtship and Marriage of Cho Kim Leong and Yeo Koon Neo

The marriage between my grandfather, Cho Kim Leong, and my grandmother, Yeo Koon Neo in 1934, was not strictly an arranged one. They were allowed to go on dates. Koon Neo’s mother and her cherki-kaki ( a favourite Peranankan card game with Nonynas) who were good friends, decided to find husbands for their daughters when they came of age. Both their daughters were of the same age and naturally became best of friends. So the 2 elders left word in the cherki-playing circles in Singapore that they were “cari kia-sai” (looking for a son-in-law). Grandmother’s only request to her mother was that she wanted a Peranakan husband who was educated and could take care of her as she was illiterate. (Editor’s note: To learn about Peranakan culture, click here.)

Cho Kim Leong was introduced to grandmother’s friend and a certain Lee Yong Teck was introduced to my grandmother. However, in a twist of fate, it was discovered that both Kim Leong and his new-found date shared the same surname “Cho”. The witty elders decided on a quick-fix solution … why not they swap partners, as both men were equally eligible. Little did they know that the two Cho families had different ancestry – my grandfather was Hokkien while his new-found date was Cantonese. Therefore, even though the spelling in English was identical, their Chinese character was different.

While the present-day couples would go on dates privately, my grandparents dated each other with their couple friends in tow. They went for trishaw-rides, watched movies, strolled along the Esplanade and chatted over meals. The closest physical contact that my grandfather had with grandmother was holding her hand. Even then, she was bashful initially and retracted her hand.

Hanging Out in the 1930's at Esplanade. (Source: http://www.singaporephotographs.com/2011_04_01_archive.html)

They were married less than a year after their first date. Grandfather immediately whisked her off to Malacca where they settled for 2 years, before grandmother convinced him to relocate in Singapore at 421 Joo Chiat Road. They had 2 sons. My father was the elder. By this era, most Peranakan couples had opted for a Western-style wedding. It was less elaborate and less costly. However, the fashion in Singapore lagged behind those of the West by almost a decade. You would notice that in the wedding portrait that the gown and veil were those popular in Europe in the 1920s. A marriage certificate was not compulsory then. My grandparents solemnized their marriage at the ancestral altar, witnessed by family members. The colonial government recognized such marriages as legal and binding.

Thanks to a twist of fate, this was the result. The picture of the Cho family shows Norman’s grandfather Cho Kim Leong, carrying his toddler son (Norman’s father) in the centre of the picture. His wife, Norman’s grandmother, is in the white kebaya seated in front of him) and includes the Tay family (from Norman’s fourth grand-aunt, who was his grandmother’s sister). This extended family portrait was taken in the front compound of the house at Joo Chiat Road. The row of shop houses in the background still stands today.

” an article first published in The Peranakan, Issue 3, 2011, pp. 3. Reproduced courtesy of The Peranakan Association, Singapore”

Recent Comments