by Jason Kuo ( 郭子澄)

A unique feature of some of the graves in Bukit Brown is the inclusion of the “Emperors’ Regnal Years or Eras” inscribed on the tombstones. Just as the British refer to the Victorian or Edwardian eras and America, the antebellum years, the regnal years speak to the milieu of the times under each emperor’s rule.

The regnal years are also sometimes combined with the Chinese zodiac year (天干地支), which is a 60- year cycle with each year represented by one of 12 animals (十二生肖), and each animal appearing five times in the cycle to form 60 years.

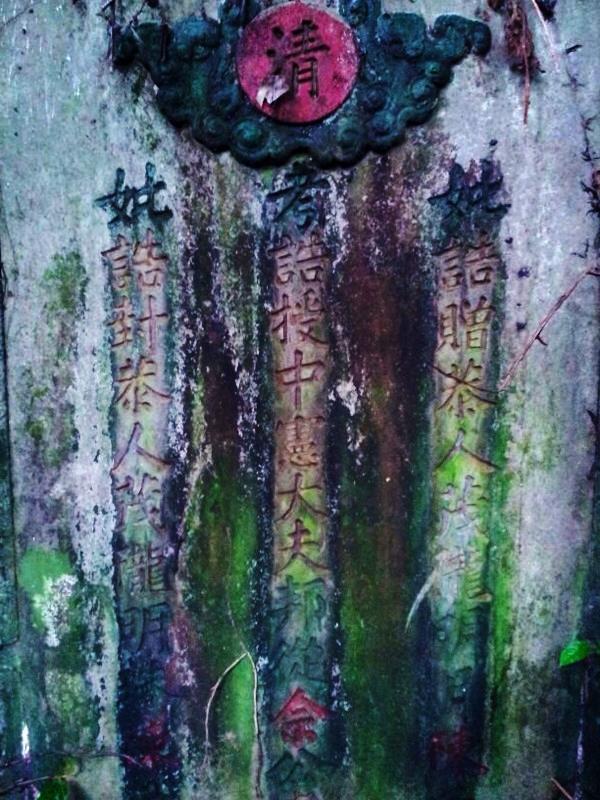

The inscription on this tomb in the Greater Bukit Brown area is of the 34th year of the Emperor Guangxu (光绪)and the zodiac year of the monkey. Guangxu’s first year of rule began in 1875, so his 34th year would be 1908 of the Gregorian year which was the year of the monkey. The deceased died in 1908, also the year Guangxu died.

With the exception of a long-reigning emperor, such as Qianlong (乾隆), any zodiac year most likely falls only once during each emperor’s reign in the last 150 years of the Qing Dynasty (清朝). For example, the year jiawu (甲午) – the year of the horse – only fell once during the reign of Guangxu. Thus the Jiawu of the Guangxu reign (“光緒甲午年”) is roughly 1894 of the Western era. This was the year of the First Sino-Japanese War, when Taiwan was ceded to Japan.

Four years later in 1898, Emperor Guangxu launched his abortive reform programme. Known as the 100-days reform (百日维新), its failure led to the execution of martyrs, the house arrest of the emperor (and continued rule by the Empress Dowager Cixi 西太后慈禧), and increasing radicalization of Chinese intellectuals. Emperor Gyangxu’s reign, was marked by defeat at the hands of the Japanese, and failure to push through reforms aimed at improving the lives of the Chinese.

Xinhai (辛亥)– the year of the pig – in 1911 was the year of the Wuchang Uprising (武昌起义) that eventually toppled the Qing dynasty. With the demise of the Qing dynasty, the “reign” title becomes Minguo 民国(民國), the republic.

This tomb shows the Mingguo year 32 on the left shoulder. Add on 11 and the year of death is 1943 in the Gregorian calendar, when Singapore was under Japanese occupation. The tomb is also inscribed with the Japanese Imperial calendar year of 2603 on the right shoulder. The Imperial year 1 (Kōki 1, 皇纪) was the year when the legendary Emperor Jimmu (神武天皇) founded Japan in 660 BC, according to the Gregorian calendar. By subtracting 660 from the Japanese imperial calendar year of 2603, we arrive at the equivalent Gregorian year of 1943.The tomb belongs to Dolly Tan whose name is inscribed in Japanese as : “Do-Ri-Tan,” to the the right of the Chinese name.

Taiwan still uses the Minguo “reign” year calendar, alongside the Gregorian calendar. This year, 2013, is Minguo 102.

About Jason Kuo (郭子澄): Born in Taiwan to mainland Chinese parents, Jason came to Singapore when he was six. Educated in Nanyang and Chinese High, he was drawn to Chinese history in particular, because as a child of of refugees, he wanted to understand his roots. He says growing up in Singapore was a wonderful experience as he was exposed to a great variety of languages and cultures. Jason, now works and lives in Hong Kong.

Further observations by the writer on the inscriptions on Dolly Tan’s tomb:

The modern Japanese dating system is identical to the Chinese imperial system. Each emperor’s reign is marked by a reign title. The current emperor’s reign title is Heisei 平成, beginning in 1989. The prior emperor ascended the throne in 1925, and was one of the longest serving monarchs in history. The Showa 昭和 reign began in 1925, and covered the years when Singapore was brutally ruled as Shonan-To 昭南島 [i.e., the southern island of Showa]. As the old emperor entered his 60th year of reign, the Japanese government was still putting out budget proposals that extended to Showa 100 or beyond, since an emperor’s mortality should never be questioned. I’m also intrigued that the tomb uses the lunar dating system even though the year is already Minguo [Minguo 32. 5th day of 4th moon], but in the Japanese rendition it kept the Gregorian system [Imperial year 2603, June 28]

As part of Bukit Brown : Our Roots, Our Future, a series of talks were programmed to enrich the exhibition which was held at the Chui Huay Lim Club, the co-organiser of the exhibition.

Speaker Dr Imran bin Tajudeen gave insights into Singapura’s Historic Cemetery at Jalan Kubor which has royal roots. Several old settlements existed in Singapore besides the Temenggong’s estuarine settlement at Singapore River before Raffles’ arrival in 1819. Among these, Kampung Gelam and the Rochor and Kallang River banks were also sites of historic graveyards related to old settlements of Singapura both before and during colonial rule. The Jalan Kubor cemetery is the only sizable cemetery grounds still largely undisturbed. It belongs with Kampung Gelam history but has been excluded from the “Kampong Glam Conservation District” boundary, and is important for several reasons. It forms part of the old royal port town that was developed when Tengku Long of Riau was installed as Sultan Hussein in Singapore, and is aligned along the royal axis of the town. It is also the final resting place of several traders of diverse ethnicity from the old port towns of our region – neighbouring Riau, Palembang, and Pontianak, as well as Banjarmasin and the Javanese and Bugis ports further afield. Some of these individuals are buried in family enclosures, mausolea, or clusters. Conversely, there are also hundreds of graves of unnamed individuals from Kampung Gelam and surrounding areas. The tombstone forms and epigraphy reflect this immense socio-cultural diversity, and were carved in Kampung Gelam by Javanese and Chinese stone carvers, except for a number of special cases. Several large trees of great age are also found in this lush ‘pocket park’. The talk discusses the histories that can be retrieved from this important site and the dire need to protect it.

Speaker’s Bio

Dr Imran bin Tajudeen is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, NUS. His research interests centre around vernacular urbanism, house and mosque architecture in Southeast Asia, and critical perspectives in urban heritage studies. Of relevance to this talk is his article, ‘Reading the Traditional City in Maritime Southeast Asia: Reconstructing the 19th century Port Town at Gelam-Rochor-Kallang, Singapore,’ published in the Journal of Southeast Asian Architecture in 2005. His research papers have won prizes at major international conferences, including the ICAS Book Prize 2011 for the best PhD paper in the field of Social Sciences.

———————————————————————————————————

Part 1 and Part 2 of theEnglish talks from other speakers are also available.

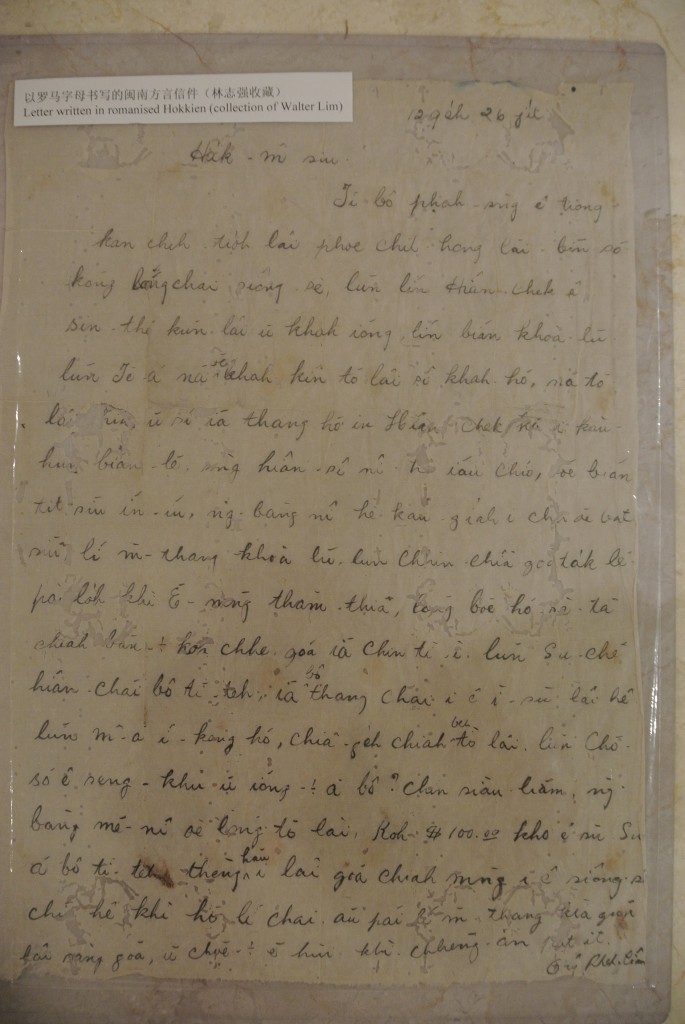

A letter in Romanized Hokkien , or Pe̍h-ōe-jī as it is known, on display at the exhibition Our Roots, Our Future, piqued the interest of many. But no one could fully decipher its meaning. A challenge was sent out to the Singapore Heritage Bukit Brown Cemetery FB group. It caught the eye of 卓育興 Yu Hsing Jow who is a Taiwanese living in Singapore researching on Hokkien culture here. He alerted an expert from Xiamen, Lim Kian Hui. who was able to help decipher and translate the the letter.

卓育興Yu Hsing Jow translated it into Mandarin, and from Mandarin, we finally have an almost full English translation by Brownie Ang Yik Han. It reads:

Hàk-ḿ: (the letter is addressed to a woman named Hak)

I received a letter out of the blue which covered many details. Your uncle’s health is better, please don’t worry. If his son can return it will be better, as your uncle can teach and encourage him. He is young and susceptible to temptations, hopefully he will be wiser when he is older, please don’t worry. As for the relatives, they are not in good condition when I visit them in Amoy every week, but I am not too concerned. Your senior is not here now, I have no wish to inform her as well, but she will be back in the first lunar month. How are the sisters-in-law? They are so young, I wish they can be back every year. Also, there is the matter of the $100. The teacher is not in school, I will enquire about him later. As for this mark (unclear what this is) , please do not send it to me in the future, it takes a lot of effort. Take care.

The content is representative of letters that would have been exchanged by families and friends separated in the Chinese Diaspora. It covers in one page an update on financial matters and the domestic situation at home, but the tone of the letter also expresses care, concern and reassurance.

Here is the letter transcribed in Pe̍h-ōe-jī by 卓育興 Yu Hsing Jow

Ha̍k-ḿ siu

Jí-bô phah-sǹg ê tiong-kan, chiap-tio̍h lâi phoe chit hong, lāi-bīn sō kóng long chai siông-sè . lūn lín hiân-chek ê sin-khu, kūn lāi ū khah iōng, lín bián khoà-lū. lūn jī á nā-sī khah kín tò-lâi pó khah hó. Nā tò-lâi chia, ū sî iā thang hō͘ in hiân-chek khah I kàu-hùn, bián-lē. sǹg hiân-sî nî-hè iáu chió, bē bián tit-siū ín-iń, ng-bāng nî-hè kàu gia̍h i chiū ē bat siūⁿ . lí m̄-thang khoà-lū. lūn chhin-chiâⁿ goá ta̍k lé-pài lo̍h khì Ē-Mn̄g thām thiā, long boē hó-sè. Tā-chiah chia bān-bān koh chhōe, goá iā chin tì-ì . lūn su-chē hiân-chai bô tī the, iā thang chai ié ī-sū. Lái heⁿ lun̄ mā ái kóng hó, chiaⁿ-ge̍h chiah beh tò-lâi. Lūn chō sō ê seng-khu ū ióng-ióng á-bô. Chin siàu-liân ǹg-bāng mê-nî ē long tò-lâi, koh $100.00 kho ě sū. Suá bô ti-teh thēng hāu-lâi,góa chiah mn̄g I ê siông-sè, chit ê kì-hō,lí chai āu-pái m̄-thang kià kòe lâi sàng góa, ū chōe chōe êhùi khì. Chhéng an put it.

Ông pheh lîm

Many thanks to 卓育興 Yu Hsing Jow for the transcription and his time spent in helping to translate the letter. He has since included the letter to the Wikipedia on Singaporean Hokkien

About the letter:

The Letter was donated to the exhibition Bukit Brown: Our Roots,Our Future, by a descendant of Tan Boon Hak, cousin of Tan Kah Kee)

As part of Bukit Brown : Our Roots, Our Future, a series of talks were programmed to enrich the exhibition which was held at the Chui Huay Lim Club, the co-organiser of the exhibition..

Here is Part II of the video recordings, released with permission from the speakers. Part 1 is available here

5 th July, 2013

Chan Chow Wah – Screening of “Light on the Lotus Hill” and post-screening talk

Light on the Lotus Hill” is a research project by Chan CW to document a chapter of the almost forgotten history of Singapore and World War Two. After 5 years of research in Singapore, China, Malaysia, and UK, the book was published on 28 May 2009. It documents the life of a Buddhist monk, Venerable Pu Liang, who supported China Relief Fund’s fund raising activities in Nanyang, today’s South East Asia. The Venerable also offered temple grounds for the training of Nanyang Volunteers who later drove on the Burma Road.

After the fall of Singapore, the Venerable was executed by the Japanese during the Chinese massacre. During the research, a British POW’s daughter helped provided vital evidence as her father, a British POW at Changi, witnessed the execution. This research offers an alternative understand of World War Two and how Nanyang Chinese occupied multiple spaces of wars in China and Colonial Singapore. These parallel worlds collapse into one dark reality as the Japanese invaded Singapore converging Sino Japanese War with World War Two.

Speaker’s bio: By training an anthropologist, Chan graduated with a Masters in Social Anthropology from the London School of Economics. He was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow in 2006, a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute, UK, and a Member of the American Anthropological Association, USA. He is also a Member of the International Oral History Association. His publications include the book “Light on the Lotus Hill” and the article “Storm in Shuang Lin” published in the

April 2007 issue of Biblioasia.

The video has a trailer of the documentary followed by the q&a. The screening itself is not included for copyright reasons

6th July, 2013

Norman Cho – Peranakan Elements at Bukit Brown

Search for Grandpa’s Grave at Bukit Brown and Search for My Ancestry. Discovery of Bukit Brown as the Resting Place of Early Peranakans. A Study of Peranakan Elements like Tiles, Benches, Gates, Stone Carvings and Jewellery worn by the deceased.

Speaker’s bio:

An IT professional who researches on Peranakan material culture, Norman is active in sharing his findings on the internet and through talks.

7th July, 2013

Dr Lai Chee Kien – The Material Culture of Bukit Brown

The Bukit Brown Municipal Cemetery is an important manifestation of the period that consolidated overseas Chinese identity in Singapore. Prior to this period, dialect affinities resulted in spatially-distinct residential enclaves as well as separate burial sites such as the Kwong Hou Sua for Teochews, and Peck San Theng for the Cantonese.

The cemetery at Bukit Brown allows us to examine history through its material culture as well, such as the wide range of materials used for the graves’ construction, like greenstone, granite, bricks, decorative tiles as well as Shanghai plaster. They point collectively to the dedication and wealth bestowed on such afterworld abodes, and to the craftmanship that existed on the island. The epigraphic material may also be deciphered as heritage, and permit the reconstruction of the larger Nanyang community that included Singapore.The talk is an attempt to document such efforts, and to illustrate their importance for Singapore’s collective memory.

Speaker’s bio: Lai Chee Kien is Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore. He is a registered architect, and graduated from the National University of Singapore with an M Arch. by research [1996], and then a PhD in History of Architecture & Urban Design from the University of California, Berkeley [2005]. He researches on histories of art, architecture,settlements, urbanism and landscapes in Southeast Asia. His publications include A Brief History of Malayan Art (1999), Building Merdeka: Independence Architecture in Kuala Lumpur, 1957-1966 (2007) and Cords to Histories (2013).

A very big THANK YOU to Brownie Ang Hock Chuan for videoing the talks!

Tan Seng Chong (1874-1927)

by Dr. Lai Chee Kien

Tan Seng Chong (1874-1927), architect and director of Tan Seng Chong & Co., was listed as the first Chinese person to commence his own architectural practice in Singapore (i.e. as sole proprietor). Born on the island when it was part of the Straits Settlements in 1875, he was educated at Raffles Institution before joining the Singapore Municipality as an apprentice in 1897.

After serving there for 13 years, he commenced private practice in 1910. His office on the top floor of 14, Raffles Quay employed an assistant manager (E.D. Cashin), a chief draughtsman (H. Amin) and an overseer of work (Syed Hamid). The firm also billed itself as surveyors and building agents, and undertook a range of work including the design of the Empire Cinema at Neil Road (1916), works on a Chinese temple (1919), factories, depots and industrial structures.

He designed many bungalows, houses and stretches of shophouses including seven (Nos. 4 – 16) at Emerald Hill Road. His clients included many notables of the day, like Lim Peng Siang, Tan Kah Kee, Tan Chay Yan and Eu Tong Sen. Tan Seng Chong is buried with wife and their tombs are in the way of the proposed highway.

Stake numbers : 1945 and 1946 at Hill 2 in Bukit Brown

The twin tombs of Tan Seng Chong (1945) and wife (1946) in the background, with students documenting the staked graves (photo by Lai Chee Kien)

The Rojak Librarian has more on the life and times of Tan Seng Chong and his family.

Dr. Lai Chee Kien is an architectural historian and Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore

Lai Chee Kien at a recent talk he gave on the material culture of Bukit Brown (photo by Bianca Polak)

You can view Dr Lai’s talk on the material culture of Bukit Brown here

by Grace Seah

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Maya Angelou

In memory of my Uncle Tan Kim Cheng

One might wonder what has WWII & Operation Sook Ching has to do with Bukit Brown as a place in our history.

Among the men, women and children buried at Bukit Brown were victims, killed by the Japanese during the war. Many lived through that tumultuous period in Singapore’s history and carried with them the pain and heartache of not knowing where their son or daughter went during the war, never to be seen again.

This is a story of one such family – my family.

In an earlier blogpost about my grandparents, I shared a much loved family photo which included my grandparents, my father and his 2 elder brothers. One of his brothers was taken by the Japanese that one fateful day in Operation Sook Ching and my grandparents never saw their third son ever again.

Just what was Operation Sook Ching ?

According to the heritagetrails.sg website

“A decree was issued on Wednesday 18 February 1942: All Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 in Syonan-To (as Singapore was called during the Japanese Occupation) were to report to the various registration centres around the island. The decree embodied Japanese hatred for the Chinese, cultivated through years of Sino-Japanese war since 1937. Also, overseas Chinese had been quickly labelled anti-Japanese due to their contributions to war efforts in China. Thus began the Sook Ching operation, or the elimination of anti-Japanese elements.”

A story that is often told in our family revolved around the time my father, Tan Kim Huat – youngest son of Tan Keng Kiat and Chan Gim Neo, – was rounded up by the Japanese, together with his third brother Tan Kim Cheng. Both were taken to a holding area with many other young Chinese males in the vicinity. They were not told of the reason for their detention, but they were all held like prisoners surrounded by fiercely guarded fences and barriers.

Many like my father experienced the sheer terror of not knowing what to expect from their captors that drove them to despair and desperation. Many never lived to tell their story. My father did.

On the night of their capture, my father had a premonition that all of them were going to be killed the next morning. He heard his inner voice telling him to run for his life and resolved to find a way out no matter what. At 22 years of age, my father possessed the courage and brashness of youth which stood him in good stead in this instance.

He sought out his elder brother and told him of his plan to escape. My uncle being of a different nature just could not find it in him to make that dangerous journey. My dad, not being able to convince his brother to follow suit, then decided to make a run for it in the middle of the night.

Whatever possessed my father to take that perilous journey, to this day, he cannot say. But with his every being pumped up with adrenalin, he did the unthinkable and scaled a secured fence and ran away to freedom, all the time expecting a bullet to his back.

Imagine my grandparents’ elation and at the same time heartache when my dad ran home that day but without his brother. The next morning, my aunts went to the place of detention to look for my uncle but never found him again. He was presumed dead, and I believe, his name is engraved amongst those of the many civilian war victims at the Civilian War Memorial near the Padang.

As for the young women, my mama (grandma) had to urgently find a couple of single men willing to take my unmarried aunties as wives at short notice so as to protect them from the Japanese. My aunts were married off to non Peranakans from humble backgrounds. Both my uncles ended up being good men who looked after my aunts and the children that followed as best as they could.

If my aunts had not been hurriedly married , they would most certainly have been taken by the Japanese to be comfort women. If my father had not been so brave, I would not be here today.

We must therefore never forget the courage and spirit of the people of Singapore during the early years. Their blood flows through us, because of them, we are here.

My father on the extreme left beside his mother (my grandma) and next to her my Uncle Tan Kim Cheng who was lost to Sook Ching ( Family Album )

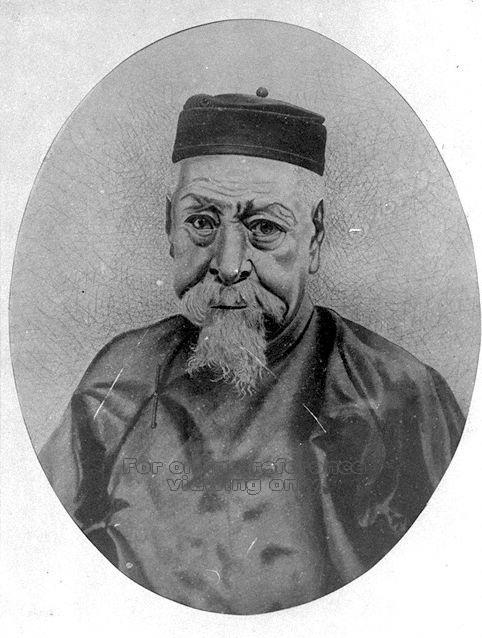

Seah Eu Chin (1805-1883)

Singapore’s Pioneer Gambier and Pepper Plantation King

Founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi

It started with a breaking news flash on the Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook page posted by Raymond Goh just after 2 pm on Friday 16 November 2012:

“Breaking news….the Goh Brothers have found the triple tomb of one of foremost Teochew pioneers of Singapore – Seah Eu Chin and his two wives, sisters of Tan Seng Poh. Details to follow…”

This was followed by the first photo of the tomb described as :

“Tomb of Seah Eu Chin, founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi, with his two wives Tan Beng Guat and Tan Beng Choo. Eu Chin passed away in 1883. We will take exact measurements tomorrow, but his tomb is believed to be as big as Ong Sam Leong.

Tomb of Seah Eu Chin, founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi, with his two wives Tan Beng Guat and Tan Beng Choo. (photo Raymond Goh)

The tomb inscriptions included imperial titles, but Raymond reports, reading the inscriptions is proving a challenge as some of characters are missing. The lettering is done with some kind of metal which has fallen off.

This is Charles’ account of the search for Seah Eu Chin

“Like the previous finds of Ann Siang and the elder Gan, minutes before the find, there will be rain. For Seah, there were additional ‘help’. On the 1st day, a cobra reared its head preventing us from going one way. Another hissed to stop our tracks when we tried another way. And we met a monitor lizard on the start of the 3rd route. Thinking something’s wrong, we stopped our search minutes after we started. (After Eu Chin’s find, we knew we had went the wrong side of the hill then.) The 2nd day we tried a new location. The trek was smooth, and when rain fell, a sense of hope, and there rose a feeling that something was right. We found it in 10 minutes.”

The next morning, the Goh brothers were back at the grave and posted a photo of the grave in full glory:

The brothers have cleared a path towards the grave so his descendants, members of the Teochew Community and Brownies can visit later. The location of the grave is under wraps at the moment until such time as the descendant who made the request for help to find Seah Eu Chin is informed.

An extract on Seah Eu Chin from The Straits Times, 24 Sept 1932, Page 12

Chinese Benefactor of 1845 – Ngee Ann Kongsi:

In or about the year 1845 the late Seah Eu Chin, at that time a prominent Teochew merchant in Singapore and 12 other Teochew merchants then in Singapore, promoted the formation of a fund for the propagation and observance in Singapore of the doctrines, ceremonies, rites and customs of the chinese religions as observed by the Teochew community, a community of Chinese originating from certain districts in the Kwantung Province of China, and for other charitable purposes for the benefit of the members for the time being in Singapore of the Teochew community…

There is a blog post on Seah Eu Chin here.

Related Post:

The Origins, Traditions and Beliefs of what today has become popularly known as “The Hungry Ghost Festival”

by Victor Yue

Between the ancient Chinese characters and the modern English vocabulary, there seems to be a big mis-match as to what the festival is about. But for ease of communication, some terms that seem to be closest in translation would it seems, have to do. In some cases, such as events, more exciting phrases were coined in Chinese and explains I believe how we have arrived at the name The Hungry Ghost Festival.

The Origins

It is said that although the 7th Month event is an age old tradition and custom from ancient times marked during the 7th lunar month, the term “Gui Jie” meaning Ghost Festival did not appear until the Ming Dynasty. I am curious as to when the word “Hungry” was added into the Ghost Festival, making it the Hungry Ghost Festival. Indeed this additional adjective does much to fire up the imagination of the more impressionable young and those unfamiliar with the 7th Month event.

Older Chinese, simply call it Chit Gue (7th month in Hokkien), Por Tor (Pudu in Mandarin) or Tiong Guan Huay (Zhong Yuan Jie) which is probably more official as these are the words used in the posters and banners put up during this time.

As with most age old traditions, it’s difficult to separate the practice, beliefs and the myths. We tend to embrace them together and it becomes a colourful, cultural potpourri

How is it “celebrated”?

The 7th Month in Singapore means different things to different people. To believers and those who have “the third eye”, it is a month when the entities of the nether world come a calling. “Don’t go out late, Don’t go swimming” would be the warning from Grandma. The grandchildren would dutifully say “yes” and do exactly the opposite! And should anything untoward happen, Grandma would say “I told you so!” and follow up with making reparations to ask the “invisible” for forgiveness.

For the Hokkiens and Teochews (and probably for other dialect groups as well), on the first night of the 7th month, they would be lining up candles and joss-sticks to “welcome” the visitors (who might include their ancestors) offering them food and burning joss-papers (money). They do the same on the last day of the 7th month to send them off. In between, on the 15th day, they would also d0 another similar round of offerings. For the Cantonese, I understand that they do it on the 14th night of the 7th month.

A few days before the arrival of the 7th month, the organisers of the neighbourhood’s 7th Month prayers – officially called “Celebrating Zhong Yuan Jie” – will set up make-shift altar tables at a suitable place, usually close to a lift landing or a corner of an HDB block Some HDB block or blocks may have more than one group of Zhong Yuan Jie organisers. Most of these organisers would have continued since the days when the residents were from a different neighbourhood. They tended to follow the migration of many of the residents from the old houses (kampong /pre-war homes) to their new homes in housing estates.

Back in the good ole days….

In the old days (circa 1950s), this event lasting between one and three days in any neighbourhood was one that the kids look forward to. Most families would subscribe to one of the Zhong Yuan Jie (or Por Tor in Hokkien) having paid a dollar a month. During the Por Tor, the organisers would have the goodies as offerings to the Por Tor Gong (the Tai Shi Ya or Da Shi Ya) before giving each subscribing household a pail of these goodies.

Apart from the 7 essentials (柴米油鹽醬醋茶- charcoal, rice, oil, salt, soya sauce, vinegar and tea – what’s needed in a typical kitchen of the old days ) there might be half a braised duck or chicken, something that was a luxury in the 50s for most families. There would also be an abundance of fruits – from Rambutans to Buah Langsat to Buah Duku.

For children, it was like carnival time. Street wayangs – about the only open air entertainment and free to boot of those times, would spring up. They were set up so skilfully within half a day using only mangrove poles tied together by soaked split rattan, and wooden planks for the flooring. I remember taking a stool from my house to “chope” (reserve) a place to watch. The afternoon show was from 2pm to 5 pm and evening from 8pm to midnight. Food was close at hand. Hawkers would encircle the wayang stage and even underneath the raised stage, selling food such as oh-jian (the traditional barnacles in fried sweet potato flour with eggs ), traditional desserts (offerings from red bean soups to sweet potatoes to tau suan and bubur telegu), fried kway teow, shellfish (cockles and siput) and much, much more. And when I was bored with the wayang I would take a turn at the games station and try my luck at tikam-tikam – just folded paper that for 5 centsa pick, you get a a shot at winning a prize of some cheap toy or sweets. I hardly ever won anything.

In the streets of Chinatown

In the Chinatown of old, each house would, in step with the organising communities for Por Tor, set up their altar tables outside their house to make offerings. As the majority of such houses had multiple tenants, the landlord would lead in organising the prayers. The narrow streets meant street wayangs were allocated specific dates for the Por Tor. One would be able to see the offerings from the beginning to the end of the street, with the triangular flags stuck into the food/fruits fluttering in the wind.

Sometimes, the community prayer ends up with a grand dinner where items are auctioned off and money raised – the collection of which could take up to a year – for the next Por Tor. The funds help to pay for not only the event but also the food baskets.

Enter the getai …

Getais came on the scene in theearly 60’s and overtook the wayangs in popularity (photo by Victor Yue)

Getai probably started in the 60s and quickly held the crowd captive. But long before their entry, some street wayangs had some of their actors/actresses singing before the opera started, as a warm up act, but it did not develop further. It took off probably following the hey day of the wildly popular Wang Sar and Yueh Fong. The duo took Singapore by storm and everyone knew the exclamation “Wah Lao”. During that time, there were also the Getai entertainment establishments where one could pay for entrance and get a drink to watch. The last one, similar to those in Taiwan, to my memory must the one at the former Wisma Atria, which I would go with my classmates each Chinese New Year eve.

In Chinese temples

In the Chinese Temples, the offering on the 15th of the 7th month was to Di Guan, one of the three Officials of the three realms – Tian (Heavens): celebrated on 15th of 1st Lunar Month), Di (Earth): celebrated on 15th of 7th Lunar Month and Shui (Water): celebrated on 15th of the 10th Lunar Month.

According to Taoist beliefs, praying to Di Guan is to ask for elimination of sins and debts. It is from this occasion of praying to the Di Guan or Di Yuan that the world of Zhong Yuan Jie came about.

Family….

For the family, 7th month is also a time for them to remember their ancestors. During the old days, each family, would have their ancestral altar at home. For the Hokkiens it would usually be placed next to another altar dedicated to Tua Pek Kong. For their most recently departed – a parent or grandparent – the family, usually the grandma or mother would prepare the offerings. The departed and the ancestors further down the line would be’invited” to come and partake of the offering. For us kids, it was also another occasion we waited for, for it meant that we could have more elaborate dishes that we would not get otherwise. Chinese New Year and 7th Month are the two major occasions that children look forward to and our poor parents would dread it as they would need to find money to cook up at least something worthy for their ancestors.

Today, many would have have moved the family ancestral tablets to the temples and so, offerings would be at the temples. Food offering’s also became simplified with fast food that could be the packed from chicken rice to Kentucky Fried Chicken.

7th Month represents a spectrum of Chinese culture, of beliefs, tradition and customs, with variations for different dialect groups, and in some instances also influenced by the practices from ancestral place of origin in China. We remember our ancestors; we think about the wandering souls (those whom the descendants have forgotten or who may no longer have living descendants); we seek pardons from the Official of the Earth Realm. This we do, to preserve our unique culture which also evolves with the times.

Victor Yue is Taoist and spends much of his time researching and documenting Chinese religious practices and rituals.

Here is a video he took on a auction on Pulau Ubin for the Hungry Ghost Festival

Here is another of Victor’s video on “Breaking Hell’s Gates” – a rare ritual conducted only once every 5 years at Peck San Theng Temple in Bishan

At Bukit Brown during the 7th month, tour groups also encounter evidence of rituals and offerings

It was the inaugural Revolutionary Tour so dubbed because the tombs visited belong to the revolutionaries of the Tong Meng Hui. They made Singapore a base to raise funds to support Sun Yat-Sen in bringing about the fall of the Qing Dynasty who ruled between the 1905 – 1911. it was popularly called the “辛亥革命” (Revolution of the Xin Hai Year) Post 1911 they continued to play a part in influencing the course of China’s history and also contributed to Singapore’s social, economic and community development.

Walter Lim led the tour conducted in Mandarin for some 36 guides from the Sun Yat Sen museum, many of whom also guide in Mandarin at the Singapore History and Peranankan Museums. He was assisted by volunteers, Yik Han and Ee Hoon. As tours went, it was one of the most engaging and lively of tours conducted at Bukit Brown, with participants sharing their insights and postulating various theories. It took nearly 5 hours to cover just under 10 tombs. There are 13 known TMH tombs and 14 tombs known to belong to Republicans – the latter was formed after TMH at Bukit Brown. Collectively both groups were part of the Reformation movement of the New China.

The following is a photo essay report with photos by Ee Hoon and captions contributed by Walter and Yik Han. Of the tombs covered 3 belong to Republicans: Khoo Seok Wan, Leow Chia Heng and See Tiong Wah . The rest are Tong Meng Hui

First stop Tay Koh Yat. At the height of his business he owned a total of 163 buses serving public transportation. He was a patriot who started and led his own self defence force of 20,000 before the onset of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore in World War 2. With a price on his head, Tay escaped to Indonesia with Tan Kah Kee on the eve of the war. After the war, Tay returned and immediately started to compile the fatalities from his volunteer force and lobbied the colonial government for the same compensation given to widows and children of servicemen who died during the war. Initially rejected, he appealed and the colonial government finally gave in. Tay next went on to form the Singapore Chinese Appeal Committee for the Japanese Massacre victims to seek justice and compensation.

The first stop is introduction by Yik Han to Tay Koh Yat, transport pioneer, war hero and Tong Meng Hui member (photo Ee Hoon )

Stop 2, destination : the tomb of 蒋玉田(Chio York Chiang) (1856-1927). He was one of the pioneer batch of Hokkien TMH member. Others were, Tan Chor Nam, Lim Keng Chew and Liew Hong Sek.

Interesting inscription of the head stone, one side has ” 时国民党老同盟独具先“ and ”为华侨界代議士尚繋後思“ The first “He is a pioneer of the Guo Min Tang with sharp foresight” the second statement on the right says that he is a “Representative of the oversea chinese righteous member, a thoughtful person”

Around the tomb of Chio York Chiang – Buried with him is his brother, in the same tomb so the names on the tomb shoulders are those of their respective children

A tight squeeze around the tomb of Chio York Chiang which is unique in that it is inscribed with his and his brother’s, sons’ names on each of the tomb shoulders.(photo Ee Hoon )

Stop number 3 Tomb of Khoo Kay Hian and his third wife Lee Poh Neo, behind are his 2 older wives and watching over the cluster his mother. The first of the tombs on the tour which is staked for exhumation as it is in the way of the proposed 8 lane highway.

Stop 4 See Tiong Wah

Making their way to See Tiong Wah cluster in a hill once known as See Tiong Wah hill because so many of his relations including his mother, wives and in laws are buried here. This cluster is also staked ( photo Catherine Lim)

Ee Hoon takes a sip before launching into what she knows of See’s genealogy including his marriage to Khoo Seok Wan’s sister. ( photo Catherine Lim)

For more on See Tiong Wah, see here

The next stop 5, took participants up another part of Hill 2 into an overgrown tomb belonging to Boey Chuan Poh who built Wan Qing Wan

A sight of the tomb of Boey Chuan Poh, he is not a poor man but he has a really humble tomb, unmatched to his social status at that time.

Boey barely revealed. Much ado about just who/what was Wan Qing Yuan named after, mother, wife or horse? Officially it is his mother (photo Ee Hoon)

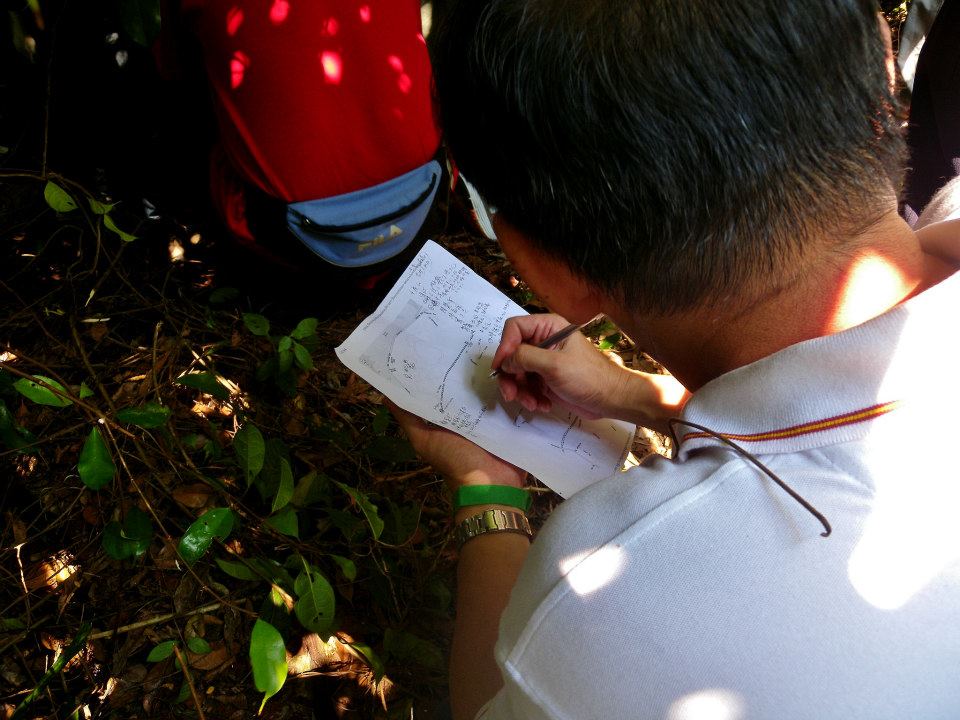

Much scribbling not just here where it was cramped but at all the tombs visited, We are expecting the tours at SYS to be much expanded as a result of this tour! (photo Ee Hoon)

Stop 6 Tan Chor Nam

Stop 7 Lim Keng Chiew

Lim was an early member of the Tongmenghui and the first secretary of its Singapore branch. He was so active in promoting the revolutionary cause that his shoe business suffered. But you say he left his footprint on the movement. He was one of the founders of the Ho San Kong Huay, a locality organisation for Hokkiens from the Ho San region in Xiamen. (Photo Ee Hoon)

Stop 8 Khoo Seok Wan

To Hill 4 and a grave marked by a hibiscus tree which always seems to be in full blossom (photo Ee Hoon)

Read about it here

A chance near where KSW tomb is located to study the LTA’s plans for he 8 lane highway and contemplate the stake tombs which are in the way, including Khoo Seok Wan’s (photo Ee Hoon)

In fact when you see these boards in Hill 4, follow it, look for the hibiscus plant and it will lead you to KSW, ironic isn’t it? ( photo Ee Hoon)

Stop 9 Leow Chia Heng

For more on Leow, please click here

Nearly 5 hours later, still enough energy for one last cheer, for more tours to come (photo Ee Hoon)

Look out for Revolutionary Tours in October in English!

Recent Comments