Sook Ching – Our Loss

7by Grace Seah

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Maya Angelou

In memory of my Uncle Tan Kim Cheng

One might wonder what has WWII & Operation Sook Ching has to do with Bukit Brown as a place in our history.

Among the men, women and children buried at Bukit Brown were victims, killed by the Japanese during the war. Many lived through that tumultuous period in Singapore’s history and carried with them the pain and heartache of not knowing where their son or daughter went during the war, never to be seen again.

This is a story of one such family – my family.

In an earlier blogpost about my grandparents, I shared a much loved family photo which included my grandparents, my father and his 2 elder brothers. One of his brothers was taken by the Japanese that one fateful day in Operation Sook Ching and my grandparents never saw their third son ever again.

Just what was Operation Sook Ching ?

According to the heritagetrails.sg website

“A decree was issued on Wednesday 18 February 1942: All Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 in Syonan-To (as Singapore was called during the Japanese Occupation) were to report to the various registration centres around the island. The decree embodied Japanese hatred for the Chinese, cultivated through years of Sino-Japanese war since 1937. Also, overseas Chinese had been quickly labelled anti-Japanese due to their contributions to war efforts in China. Thus began the Sook Ching operation, or the elimination of anti-Japanese elements.”

A story that is often told in our family revolved around the time my father, Tan Kim Huat – youngest son of Tan Keng Kiat and Chan Gim Neo, – was rounded up by the Japanese, together with his third brother Tan Kim Cheng. Both were taken to a holding area with many other young Chinese males in the vicinity. They were not told of the reason for their detention, but they were all held like prisoners surrounded by fiercely guarded fences and barriers.

Many like my father experienced the sheer terror of not knowing what to expect from their captors that drove them to despair and desperation. Many never lived to tell their story. My father did.

On the night of their capture, my father had a premonition that all of them were going to be killed the next morning. He heard his inner voice telling him to run for his life and resolved to find a way out no matter what. At 22 years of age, my father possessed the courage and brashness of youth which stood him in good stead in this instance.

He sought out his elder brother and told him of his plan to escape. My uncle being of a different nature just could not find it in him to make that dangerous journey. My dad, not being able to convince his brother to follow suit, then decided to make a run for it in the middle of the night.

Whatever possessed my father to take that perilous journey, to this day, he cannot say. But with his every being pumped up with adrenalin, he did the unthinkable and scaled a secured fence and ran away to freedom, all the time expecting a bullet to his back.

Imagine my grandparents’ elation and at the same time heartache when my dad ran home that day but without his brother. The next morning, my aunts went to the place of detention to look for my uncle but never found him again. He was presumed dead, and I believe, his name is engraved amongst those of the many civilian war victims at the Civilian War Memorial near the Padang.

As for the young women, my mama (grandma) had to urgently find a couple of single men willing to take my unmarried aunties as wives at short notice so as to protect them from the Japanese. My aunts were married off to non Peranakans from humble backgrounds. Both my uncles ended up being good men who looked after my aunts and the children that followed as best as they could.

If my aunts had not been hurriedly married , they would most certainly have been taken by the Japanese to be comfort women. If my father had not been so brave, I would not be here today.

We must therefore never forget the courage and spirit of the people of Singapore during the early years. Their blood flows through us, because of them, we are here.

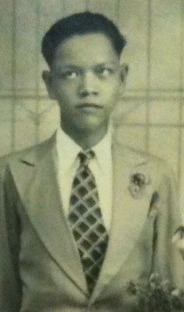

My father on the extreme left beside his mother (my grandma) and next to her my Uncle Tan Kim Cheng who was lost to Sook Ching ( Family Album )

Is this the man which the fountain at Padang was named after him?

No. That was Tan Kim Seng.

Wow… Just wow…

May the Souls of all who lost their lives in the massscre of Sook Ching Rest In Peace…