As part of Bukit Brown : Our Roots, Our Future, a series of talks were programmed to enrich the exhibition which was held at the Chui Huay Lim Club, the co-organiser of the exhibition.

Speaker Dr Imran bin Tajudeen gave insights into Singapura’s Historic Cemetery at Jalan Kubor which has royal roots. Several old settlements existed in Singapore besides the Temenggong’s estuarine settlement at Singapore River before Raffles’ arrival in 1819. Among these, Kampung Gelam and the Rochor and Kallang River banks were also sites of historic graveyards related to old settlements of Singapura both before and during colonial rule. The Jalan Kubor cemetery is the only sizable cemetery grounds still largely undisturbed. It belongs with Kampung Gelam history but has been excluded from the “Kampong Glam Conservation District” boundary, and is important for several reasons. It forms part of the old royal port town that was developed when Tengku Long of Riau was installed as Sultan Hussein in Singapore, and is aligned along the royal axis of the town. It is also the final resting place of several traders of diverse ethnicity from the old port towns of our region – neighbouring Riau, Palembang, and Pontianak, as well as Banjarmasin and the Javanese and Bugis ports further afield. Some of these individuals are buried in family enclosures, mausolea, or clusters. Conversely, there are also hundreds of graves of unnamed individuals from Kampung Gelam and surrounding areas. The tombstone forms and epigraphy reflect this immense socio-cultural diversity, and were carved in Kampung Gelam by Javanese and Chinese stone carvers, except for a number of special cases. Several large trees of great age are also found in this lush ‘pocket park’. The talk discusses the histories that can be retrieved from this important site and the dire need to protect it.

Speaker’s Bio

Dr Imran bin Tajudeen is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, NUS. His research interests centre around vernacular urbanism, house and mosque architecture in Southeast Asia, and critical perspectives in urban heritage studies. Of relevance to this talk is his article, ‘Reading the Traditional City in Maritime Southeast Asia: Reconstructing the 19th century Port Town at Gelam-Rochor-Kallang, Singapore,’ published in the Journal of Southeast Asian Architecture in 2005. His research papers have won prizes at major international conferences, including the ICAS Book Prize 2011 for the best PhD paper in the field of Social Sciences.

———————————————————————————————————

Part 1 and Part 2 of theEnglish talks from other speakers are also available.

The Cho Family Re-Discovered

by Norman Cho

The search for my family tree has been an exhilarating adventure for me…

It all began with the discovery of my late paternal grandfather’s (Cho Kim Leong) grave at Bukit Brown in Nov 2011 after a long and arduous search for it. The construction of his tomb began soon after this discovery. This was followed by more discoveries about the man (Kim Leong) himself, through family documents, interviews with those who remember him and through the artefacts that he left behind. My exciting journey in the search for my ancestors was chronologically recounted in the All Things Bukit Brown blog as more and more interesting events unfolded.

It has indeed been a blessing for me, when the spouse of a newly-discovered cousin, Richard Brockett, unexpectedly contacted me in Facebook. It was a bolt out of the blue! They were from Australia and were the descendants of my granduncle, Cho Kim Choon. Incidentally, he was reading the blogs that were posted in the All Things Bukit Brown blog. Recognising the names mentioned in the blog and touched by the accounts that I had recounted, he decided to contact me. He had just finished working on his family tree and is now working on his wife’s family tree. We were perfect in seeking each other’s help to piece together the “Cho Family Jig-Zaw Puzzle”! Somehow, I believe in grandfather’s divine intervention in making this happen.

Their family had kept a treasured family portrait of my great-grandfather, Cho Poo, with his wives and 5 sons, taken at their family home in Hereen Street, Malacca, circa 1920s. He kindly emailed me a copy of this cherished family portrait with the only known image of Cho Poo and of his wives. Finally, I was able to see my paternal great-grandparents for the very first time. The feeling was indescribable.

Great-grandfather looked stern. My great-grandmother (wife #3), Kong Moey Yean, who was dressed in a dark baju-panjang seated on the left of the picture, looked pretty much the regal matriarch. All the sons are dressed in western suit and positioned in chronological order of seniority from left to right – Kim Choon, Keow Teng, Kim Leong (my Grandfather), Kim Tian and the little boy Kim Hock who is standing beside wife #2. Like many affluent families in the Straits Settlement whose sons received an English education, they wore western suits. Although, thought to be English-educated, Cho Poo still remained a traditionalist by wearing Chinese attire in this photo. A fairly wealthy man, Cho Poo reportedly sold 5,000 acres of land in Seremban in 1895. He was a pioneer in tapioca, gambier and rubber planting who died in 1932. Little else was known about the man. Hopefully, more will be revealed as I track down more relatives from his 5 sons…

I had never thought that I would come this far… but with faith and perseverance, I know that more good things will come my way.

Editors Note: We are gratified that Norman was able to connect with a long lost cousin all the way from Australia through our blog. We salute Norman for his faith and perseverance.

Read more tips from on how to trace your ancestry from Norman here

Norman has also contributed posts on Peranakan customs and culture. Here’s a list you can click on

Pantuns , Bangsawan in Singapore , Peranakans in Mourning

Four Appointments (四聘)

by Ang Yik Han

Yet another set of four popular stories from Chinese history, this time found at the double tomb of Chew Joo Chiat and his wife, the subjects of the “Four Appointments” are two great rulers and two renowned officials who assisted their masters ably in establishing their kingdoms.

1 Yao Appoints Shun (尧聘舜)

Yao (尧), a great ruler of the Xia Dynasty (夏朝) the origins of which have been lost in time, was troubled. His son was not fit to assume the mantle of leadership and the whole land knows it. He had no choice but to hand over to someone from outside the family but a suitable candidate had to be sought. Word came to his ear of a filial young man, Shun (舜), a commoner who had lost his mother at a young age. His father’s already bad temper became worse after this and after he remarried, his affection turned from him to his new son. Shun’s stepmother and his stepbrother also treated him badly. Despite this, he was steadfast in his obedience to his parents. His filial piety was such that one day, the celestial courts sent an elephant to help him till the soil and birds to weed his fields. Yao judged that Shun was the best candidate for the position after he met him and even married his two daughters to him. Shun did not fail to disappoint and became another great ruler. The motif of the elephant in Chinese art has since been associated with peace and prosperity in the land on this account.

Shun sits by his fields as the elephant and what looks like a well-fed bird helps him out with his farming. Yao approaches from the left. (photo Yik Han)

2 Shun Appoints Yu (舜聘禹)

During Shun’s (舜) reign, floods were a constant scourge for the people. He appointed Gun, father of Yu (禹) to tackle this problem. Gun’s efforts were ultimately unsuccessful and Yu was appointed in his place. Unlike his father who tried to stem the flood waters with dams and embankments and failed, Yu created tributaries to disperse the waters. He was so dedicated to his work that he was supposed to have traveled around the land continuously for ten years. Even though he passed by his house 3 times, he did not stop to visit his family and missed his child’s birth and growing years. When he eventually succeeded in taming the waters, his knowledge of the lay of the land was unsurpassed. Coupled with his well-known concern for the people’s welfare, none was thought more eligible to take over as Shun as ruler. Till today, he is known as the “Great Yu” (大禹) in remembrance of his deeds.

Yu building a brick wall in preparation to channel the flood waters as Shun arrives on the scene. (photo Yik Han)

3 Shang (Cheng) Tang Appoints Yi Yin (商汤聘伊尹)

The last ruler of the Xia Dynasty (夏朝) was a tyrant notorious for his wanton cruelty and excesses. He paid no heed to governmental matters, which was to be his undoing. One of his vassals, Cheng Tang (成汤) saw the opportunity to advance himself, quietly built up his strength and bringing men of talent into his fold. Hearing about Yi Yin (伊尹), he visited and met him with his buffalo. Yi Yin rebuffed his invitation however, stating that he had no wish to become an official and that he had no abilities to speak of. Cheng Tang had no choice but to leave. Soon after, however, Yi Yin was brought to his attention again, such was his reputation. It was only on Cheng Tang’s third visit that he succeed in convincing Yi Yin to cast his lot with him. With his help, Cheng Tang overthrew the Xia and became the first king of the Shang Dynasty (商朝). As for Yi Yin, he is remembered as a great politician, strategist, philosopher as well as a good cook; he was adopted as one of the patron deities of cooks in China.

Yi Yin pulling his buffalo behind him as Cheng Tang respectfully makes clear his intention in meeting him. (photo Yik Han)

4 King Wen Appoints Tai Gong (文王聘太公)

During the Shang Dynasty (商朝), the Duke of the West, Ji Chang (姬昌), traveled around his realm to seek men of talent who could help him administer his domain. One day, on the banks of the River Wei, he saw an old man who was fishing with no bait, using only a bare fish hook which was straight instead of curved. When asked why he did this, the old man replied that those who were willing would be hooked voluntarily. Realising he had met an exceptional person, the Duke invited the old man into his carriage and personally pulled him along for eight hundred steps. The old man, Jiang Ziya (姜子牙), was to become the Duke’s trusted advisor and his kingdom’s chancellor, helping his son overthrow the tyrannical rule of the Shang Dynasty and establish the Zhou Dynasty (周朝). Ji Chang was given the posthumous title of King Wen (文王) after his son’s success and his able advisor was appointed as the Grand Duke (太公). This story forms part of the “Investiture of Deities” (封神演义), a fictionalised account of the Zhou’s triumph over the Shang replete with supernatural elements which has been part of popular literature and performance arts for centuries.

The Duke of the West on his way to visit the old man who waits for fish which cast themselves willingly on his hook. (photo Yik Han)

A common thread runs through the four stories: in their search for men of ability and virtue to help administer the country, rulers have to humble themselves and seek far and wide. The stories are a reminder of the respect that society is supposed to accord to the ones who have both the talent and heart to assume the mantle of government.

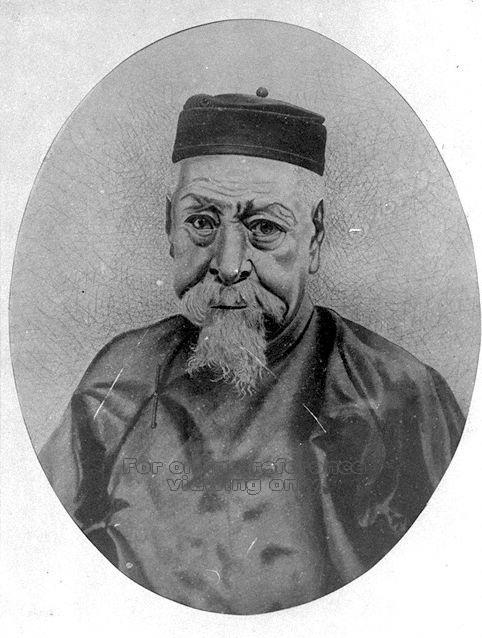

Seah Eu Chin (1805-1883)

Singapore’s Pioneer Gambier and Pepper Plantation King

Founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi

It started with a breaking news flash on the Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook page posted by Raymond Goh just after 2 pm on Friday 16 November 2012:

“Breaking news….the Goh Brothers have found the triple tomb of one of foremost Teochew pioneers of Singapore – Seah Eu Chin and his two wives, sisters of Tan Seng Poh. Details to follow…”

This was followed by the first photo of the tomb described as :

“Tomb of Seah Eu Chin, founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi, with his two wives Tan Beng Guat and Tan Beng Choo. Eu Chin passed away in 1883. We will take exact measurements tomorrow, but his tomb is believed to be as big as Ong Sam Leong.

Tomb of Seah Eu Chin, founder of Ngee Ann Kongsi, with his two wives Tan Beng Guat and Tan Beng Choo. (photo Raymond Goh)

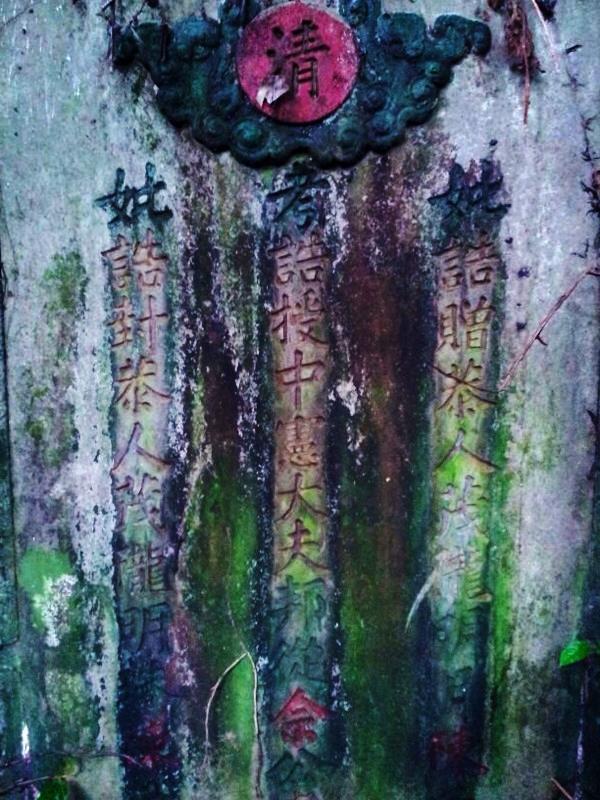

The tomb inscriptions included imperial titles, but Raymond reports, reading the inscriptions is proving a challenge as some of characters are missing. The lettering is done with some kind of metal which has fallen off.

This is Charles’ account of the search for Seah Eu Chin

“Like the previous finds of Ann Siang and the elder Gan, minutes before the find, there will be rain. For Seah, there were additional ‘help’. On the 1st day, a cobra reared its head preventing us from going one way. Another hissed to stop our tracks when we tried another way. And we met a monitor lizard on the start of the 3rd route. Thinking something’s wrong, we stopped our search minutes after we started. (After Eu Chin’s find, we knew we had went the wrong side of the hill then.) The 2nd day we tried a new location. The trek was smooth, and when rain fell, a sense of hope, and there rose a feeling that something was right. We found it in 10 minutes.”

The next morning, the Goh brothers were back at the grave and posted a photo of the grave in full glory:

The brothers have cleared a path towards the grave so his descendants, members of the Teochew Community and Brownies can visit later. The location of the grave is under wraps at the moment until such time as the descendant who made the request for help to find Seah Eu Chin is informed.

An extract on Seah Eu Chin from The Straits Times, 24 Sept 1932, Page 12

Chinese Benefactor of 1845 – Ngee Ann Kongsi:

In or about the year 1845 the late Seah Eu Chin, at that time a prominent Teochew merchant in Singapore and 12 other Teochew merchants then in Singapore, promoted the formation of a fund for the propagation and observance in Singapore of the doctrines, ceremonies, rites and customs of the chinese religions as observed by the Teochew community, a community of Chinese originating from certain districts in the Kwantung Province of China, and for other charitable purposes for the benefit of the members for the time being in Singapore of the Teochew community…

There is a blog post on Seah Eu Chin here.

Related Post:

October 13 saw volunteer guides, Walter Lim, Yik Han, Keng Kiat and Ee Hoon guiding 2 groups on a special Tong Meng Hui (TMH) Tour for museum docents and students from Pioneer JC working on a TMH project.

The tour was researched and designed by Walter who conducted the first Revolutonary tour in Mandarin also for museum docents. This TMH tour was adapted in English by the bi lingual brownie volunteer guides and co-ordinated by one f9 brownie, me 😉 The 2 tours were filmed for an upcoming documentary series on Bukit Brown.

Visiting Khoo Seok Wan, the hibiscus is always in bloom, the poet speaks through the poem he wrote for himself inscribed on his alter (photo Catherine Lim)

Read the poem here

Tie a red ribbon on a stake tomb? KSW tomb is in the way of the 8 lane highway (photo Catherine Lim)

The Republican Party was formed after the TMH. See Tiong Wah and Khoo Seok Wan are members. The party together with TMH are collectively part of the Reformation movement of new China after the fall of Qing Dynasty.

Tan Chor Nam, aka as Tan Lian Chye last and most significant stop for the docents. His photo with Sun Yat Sen is the first one which greets visitors at Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall

The docents felt that visiting the TMH tombs helped to bring these pioneers alive and they have more stories to share when they next guide at the Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall.

compiled by Catherine Lim

The Origins, Traditions and Beliefs of what today has become popularly known as “The Hungry Ghost Festival”

by Victor Yue

Between the ancient Chinese characters and the modern English vocabulary, there seems to be a big mis-match as to what the festival is about. But for ease of communication, some terms that seem to be closest in translation would it seems, have to do. In some cases, such as events, more exciting phrases were coined in Chinese and explains I believe how we have arrived at the name The Hungry Ghost Festival.

The Origins

It is said that although the 7th Month event is an age old tradition and custom from ancient times marked during the 7th lunar month, the term “Gui Jie” meaning Ghost Festival did not appear until the Ming Dynasty. I am curious as to when the word “Hungry” was added into the Ghost Festival, making it the Hungry Ghost Festival. Indeed this additional adjective does much to fire up the imagination of the more impressionable young and those unfamiliar with the 7th Month event.

Older Chinese, simply call it Chit Gue (7th month in Hokkien), Por Tor (Pudu in Mandarin) or Tiong Guan Huay (Zhong Yuan Jie) which is probably more official as these are the words used in the posters and banners put up during this time.

As with most age old traditions, it’s difficult to separate the practice, beliefs and the myths. We tend to embrace them together and it becomes a colourful, cultural potpourri

How is it “celebrated”?

The 7th Month in Singapore means different things to different people. To believers and those who have “the third eye”, it is a month when the entities of the nether world come a calling. “Don’t go out late, Don’t go swimming” would be the warning from Grandma. The grandchildren would dutifully say “yes” and do exactly the opposite! And should anything untoward happen, Grandma would say “I told you so!” and follow up with making reparations to ask the “invisible” for forgiveness.

For the Hokkiens and Teochews (and probably for other dialect groups as well), on the first night of the 7th month, they would be lining up candles and joss-sticks to “welcome” the visitors (who might include their ancestors) offering them food and burning joss-papers (money). They do the same on the last day of the 7th month to send them off. In between, on the 15th day, they would also d0 another similar round of offerings. For the Cantonese, I understand that they do it on the 14th night of the 7th month.

A few days before the arrival of the 7th month, the organisers of the neighbourhood’s 7th Month prayers – officially called “Celebrating Zhong Yuan Jie” – will set up make-shift altar tables at a suitable place, usually close to a lift landing or a corner of an HDB block Some HDB block or blocks may have more than one group of Zhong Yuan Jie organisers. Most of these organisers would have continued since the days when the residents were from a different neighbourhood. They tended to follow the migration of many of the residents from the old houses (kampong /pre-war homes) to their new homes in housing estates.

Back in the good ole days….

In the old days (circa 1950s), this event lasting between one and three days in any neighbourhood was one that the kids look forward to. Most families would subscribe to one of the Zhong Yuan Jie (or Por Tor in Hokkien) having paid a dollar a month. During the Por Tor, the organisers would have the goodies as offerings to the Por Tor Gong (the Tai Shi Ya or Da Shi Ya) before giving each subscribing household a pail of these goodies.

Apart from the 7 essentials (柴米油鹽醬醋茶- charcoal, rice, oil, salt, soya sauce, vinegar and tea – what’s needed in a typical kitchen of the old days ) there might be half a braised duck or chicken, something that was a luxury in the 50s for most families. There would also be an abundance of fruits – from Rambutans to Buah Langsat to Buah Duku.

For children, it was like carnival time. Street wayangs – about the only open air entertainment and free to boot of those times, would spring up. They were set up so skilfully within half a day using only mangrove poles tied together by soaked split rattan, and wooden planks for the flooring. I remember taking a stool from my house to “chope” (reserve) a place to watch. The afternoon show was from 2pm to 5 pm and evening from 8pm to midnight. Food was close at hand. Hawkers would encircle the wayang stage and even underneath the raised stage, selling food such as oh-jian (the traditional barnacles in fried sweet potato flour with eggs ), traditional desserts (offerings from red bean soups to sweet potatoes to tau suan and bubur telegu), fried kway teow, shellfish (cockles and siput) and much, much more. And when I was bored with the wayang I would take a turn at the games station and try my luck at tikam-tikam – just folded paper that for 5 centsa pick, you get a a shot at winning a prize of some cheap toy or sweets. I hardly ever won anything.

In the streets of Chinatown

In the Chinatown of old, each house would, in step with the organising communities for Por Tor, set up their altar tables outside their house to make offerings. As the majority of such houses had multiple tenants, the landlord would lead in organising the prayers. The narrow streets meant street wayangs were allocated specific dates for the Por Tor. One would be able to see the offerings from the beginning to the end of the street, with the triangular flags stuck into the food/fruits fluttering in the wind.

Sometimes, the community prayer ends up with a grand dinner where items are auctioned off and money raised – the collection of which could take up to a year – for the next Por Tor. The funds help to pay for not only the event but also the food baskets.

Enter the getai …

Getais came on the scene in theearly 60’s and overtook the wayangs in popularity (photo by Victor Yue)

Getai probably started in the 60s and quickly held the crowd captive. But long before their entry, some street wayangs had some of their actors/actresses singing before the opera started, as a warm up act, but it did not develop further. It took off probably following the hey day of the wildly popular Wang Sar and Yueh Fong. The duo took Singapore by storm and everyone knew the exclamation “Wah Lao”. During that time, there were also the Getai entertainment establishments where one could pay for entrance and get a drink to watch. The last one, similar to those in Taiwan, to my memory must the one at the former Wisma Atria, which I would go with my classmates each Chinese New Year eve.

In Chinese temples

In the Chinese Temples, the offering on the 15th of the 7th month was to Di Guan, one of the three Officials of the three realms – Tian (Heavens): celebrated on 15th of 1st Lunar Month), Di (Earth): celebrated on 15th of 7th Lunar Month and Shui (Water): celebrated on 15th of the 10th Lunar Month.

According to Taoist beliefs, praying to Di Guan is to ask for elimination of sins and debts. It is from this occasion of praying to the Di Guan or Di Yuan that the world of Zhong Yuan Jie came about.

Family….

For the family, 7th month is also a time for them to remember their ancestors. During the old days, each family, would have their ancestral altar at home. For the Hokkiens it would usually be placed next to another altar dedicated to Tua Pek Kong. For their most recently departed – a parent or grandparent – the family, usually the grandma or mother would prepare the offerings. The departed and the ancestors further down the line would be’invited” to come and partake of the offering. For us kids, it was also another occasion we waited for, for it meant that we could have more elaborate dishes that we would not get otherwise. Chinese New Year and 7th Month are the two major occasions that children look forward to and our poor parents would dread it as they would need to find money to cook up at least something worthy for their ancestors.

Today, many would have have moved the family ancestral tablets to the temples and so, offerings would be at the temples. Food offering’s also became simplified with fast food that could be the packed from chicken rice to Kentucky Fried Chicken.

7th Month represents a spectrum of Chinese culture, of beliefs, tradition and customs, with variations for different dialect groups, and in some instances also influenced by the practices from ancestral place of origin in China. We remember our ancestors; we think about the wandering souls (those whom the descendants have forgotten or who may no longer have living descendants); we seek pardons from the Official of the Earth Realm. This we do, to preserve our unique culture which also evolves with the times.

Victor Yue is Taoist and spends much of his time researching and documenting Chinese religious practices and rituals.

Here is a video he took on a auction on Pulau Ubin for the Hungry Ghost Festival

Here is another of Victor’s video on “Breaking Hell’s Gates” – a rare ritual conducted only once every 5 years at Peck San Theng Temple in Bishan

At Bukit Brown during the 7th month, tour groups also encounter evidence of rituals and offerings

By Eugene Tay

Eugene helms the movement “We support the Green Corridor” and is one of the partners of All Things Bukit Brown.

The Green Corridor is a former railway while Bukit Brown is a cemetery, so different yet so similar. The Green Corridor and Bukit Brown both connects the past and future, and both involves heritage and the environment. I hope that all of you can support the preservation of Bukit Brown, just as you have actively supported The Green Corridor so far.

I supported The Green Corridor proposal by NSS because I feel that it would improve Singapore’s long-term resilience. The biggest threat to Singapore is apathy, and when Singaporeans do not feel a sense of belonging and are not bothered with what goes on here, then Singapore is in trouble.

For Singapore to survive and prosper in the long term, it is necessary to have more opportunities in preserving our shared memories and creating our shared vision. And keeping the railway lands as a Green Corridor is one opportunity not to be wasted.

Similarly, I feel that Bukit Brown is another excellent opportunity that enables Singaporeans to feel they belong here by remembering our past and creating our future.

Remembering Our Past

Bukit Brown tells the stories of our forefathers who built Singapore, and creates opportunities for history education and discovery. The cemetery connects Singapore’s past and present, and allows us to understand that Singapore’s success is built up by our forefathers’ sweat and tears, and should not be taken for granted.

We should preserve Bukit Brown because it helps us remember our past and keeps us rooted to Singapore.

Intense interest in the historical tombs and shared camaraderie on public tours (photo Catherine Lim)

Creating Our Future

Bukit Brown presents the opportunity for transforming the cemetery into a world-class living outdoor museum or heritage park. If this transformation adopts a bottom-up approach and with stakeholder engagement, it would allow us to come together, plan and work towards a future Singapore where heritage, nature and our economic needs can co-exist.

We should preserve Bukit Brown because it enables us to work together and build bonds and resilience, and to create a space where our children and their children can enjoy and be proud of.

Support Bukit Brown

Singapore is a young nation and needs more common spaces like The Green Corridor and Bukit Brown to remind us how we got here and why this is home, and to create opportunities for building our future social resilience. Support Bukit Brown, just as you have supported The Green Corridor.

Here’s what you can do:

1. Sign the petition to save Bukit Brown 100% at the SOS Bukit Brown – Save Our Singapore website.

2. Join the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook Group to understand more about Bukit Brown and keep yourself updated.

3. Spread the message by sharing with your friends about Bukit Brown and urging them to sign the petition.

In the end, our society will be defined not only by what we create, but by what we refuse to destroy. – John C. Sawhill

By Eugene Tay

It was the inaugural Revolutionary Tour so dubbed because the tombs visited belong to the revolutionaries of the Tong Meng Hui. They made Singapore a base to raise funds to support Sun Yat-Sen in bringing about the fall of the Qing Dynasty who ruled between the 1905 – 1911. it was popularly called the “辛亥革命” (Revolution of the Xin Hai Year) Post 1911 they continued to play a part in influencing the course of China’s history and also contributed to Singapore’s social, economic and community development.

Walter Lim led the tour conducted in Mandarin for some 36 guides from the Sun Yat Sen museum, many of whom also guide in Mandarin at the Singapore History and Peranankan Museums. He was assisted by volunteers, Yik Han and Ee Hoon. As tours went, it was one of the most engaging and lively of tours conducted at Bukit Brown, with participants sharing their insights and postulating various theories. It took nearly 5 hours to cover just under 10 tombs. There are 13 known TMH tombs and 14 tombs known to belong to Republicans – the latter was formed after TMH at Bukit Brown. Collectively both groups were part of the Reformation movement of the New China.

The following is a photo essay report with photos by Ee Hoon and captions contributed by Walter and Yik Han. Of the tombs covered 3 belong to Republicans: Khoo Seok Wan, Leow Chia Heng and See Tiong Wah . The rest are Tong Meng Hui

First stop Tay Koh Yat. At the height of his business he owned a total of 163 buses serving public transportation. He was a patriot who started and led his own self defence force of 20,000 before the onset of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore in World War 2. With a price on his head, Tay escaped to Indonesia with Tan Kah Kee on the eve of the war. After the war, Tay returned and immediately started to compile the fatalities from his volunteer force and lobbied the colonial government for the same compensation given to widows and children of servicemen who died during the war. Initially rejected, he appealed and the colonial government finally gave in. Tay next went on to form the Singapore Chinese Appeal Committee for the Japanese Massacre victims to seek justice and compensation.

The first stop is introduction by Yik Han to Tay Koh Yat, transport pioneer, war hero and Tong Meng Hui member (photo Ee Hoon )

Stop 2, destination : the tomb of 蒋玉田(Chio York Chiang) (1856-1927). He was one of the pioneer batch of Hokkien TMH member. Others were, Tan Chor Nam, Lim Keng Chew and Liew Hong Sek.

Interesting inscription of the head stone, one side has ” 时国民党老同盟独具先“ and ”为华侨界代議士尚繋後思“ The first “He is a pioneer of the Guo Min Tang with sharp foresight” the second statement on the right says that he is a “Representative of the oversea chinese righteous member, a thoughtful person”

Around the tomb of Chio York Chiang – Buried with him is his brother, in the same tomb so the names on the tomb shoulders are those of their respective children

A tight squeeze around the tomb of Chio York Chiang which is unique in that it is inscribed with his and his brother’s, sons’ names on each of the tomb shoulders.(photo Ee Hoon )

Stop number 3 Tomb of Khoo Kay Hian and his third wife Lee Poh Neo, behind are his 2 older wives and watching over the cluster his mother. The first of the tombs on the tour which is staked for exhumation as it is in the way of the proposed 8 lane highway.

Stop 4 See Tiong Wah

Making their way to See Tiong Wah cluster in a hill once known as See Tiong Wah hill because so many of his relations including his mother, wives and in laws are buried here. This cluster is also staked ( photo Catherine Lim)

Ee Hoon takes a sip before launching into what she knows of See’s genealogy including his marriage to Khoo Seok Wan’s sister. ( photo Catherine Lim)

For more on See Tiong Wah, see here

The next stop 5, took participants up another part of Hill 2 into an overgrown tomb belonging to Boey Chuan Poh who built Wan Qing Wan

A sight of the tomb of Boey Chuan Poh, he is not a poor man but he has a really humble tomb, unmatched to his social status at that time.

Boey barely revealed. Much ado about just who/what was Wan Qing Yuan named after, mother, wife or horse? Officially it is his mother (photo Ee Hoon)

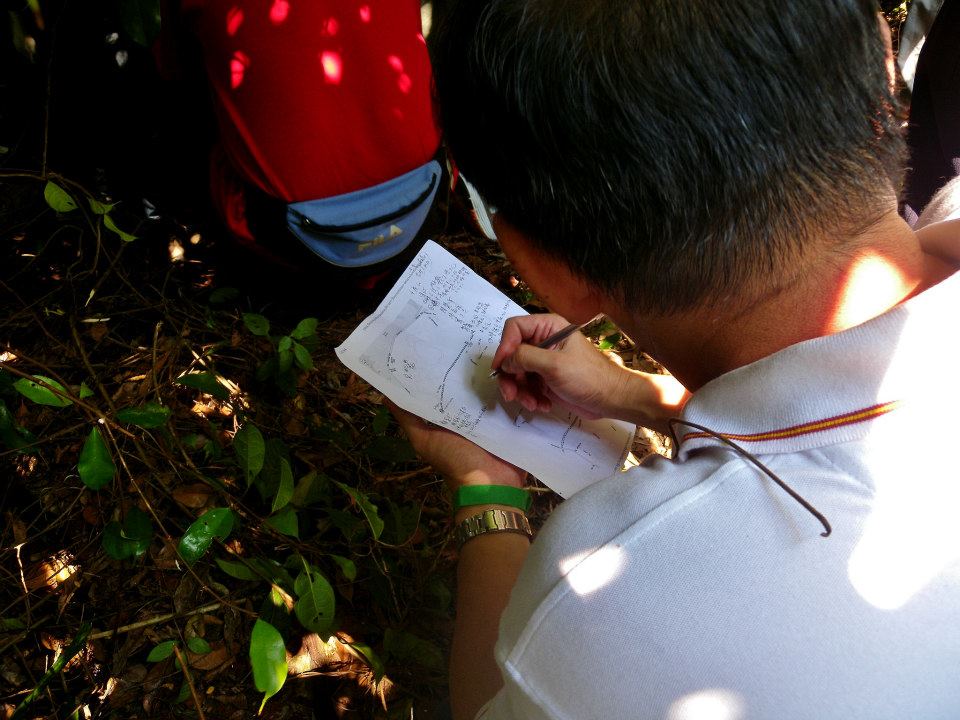

Much scribbling not just here where it was cramped but at all the tombs visited, We are expecting the tours at SYS to be much expanded as a result of this tour! (photo Ee Hoon)

Stop 6 Tan Chor Nam

Stop 7 Lim Keng Chiew

Lim was an early member of the Tongmenghui and the first secretary of its Singapore branch. He was so active in promoting the revolutionary cause that his shoe business suffered. But you say he left his footprint on the movement. He was one of the founders of the Ho San Kong Huay, a locality organisation for Hokkiens from the Ho San region in Xiamen. (Photo Ee Hoon)

Stop 8 Khoo Seok Wan

To Hill 4 and a grave marked by a hibiscus tree which always seems to be in full blossom (photo Ee Hoon)

Read about it here

A chance near where KSW tomb is located to study the LTA’s plans for he 8 lane highway and contemplate the stake tombs which are in the way, including Khoo Seok Wan’s (photo Ee Hoon)

In fact when you see these boards in Hill 4, follow it, look for the hibiscus plant and it will lead you to KSW, ironic isn’t it? ( photo Ee Hoon)

Stop 9 Leow Chia Heng

For more on Leow, please click here

Nearly 5 hours later, still enough energy for one last cheer, for more tours to come (photo Ee Hoon)

Look out for Revolutionary Tours in October in English!

By a strange coincidence, different forms of mosaic art flourished in the West and East independently of each other. The renowned Byzantine mosaics have their parallels in the “jian nian (剪黏)” or cut and paste mosaic sculptures of Southern China. This decorative technique is widely used in traditional architecture, particularly in the elaborate sculptures adorning the roofs of temples in the Fujian and Chaozhou regions. Migrants from these regions brought the technique abroad and mosaic sculptures can be seen in many traditional buildings in Singapore and Malaysia.

A cemetery is not the usual place to find an ornate temple roof but the art of “jian nian” has nevertheless managed to find its way into Bukit Brown. On Hill 4, at the tomb of Mdm Yeoh Siew Kheng (commonly known as the “5 cats” tomb due to the presence of 5 lions), a lavish display of “jian nian” mosaics can be seen. There are the five lions, a pair of male attendants and tableaux featuring the 8 immortals. Even the Chinese characters of the tomb couplets are mosaics.

Time and the elements have not been kind to these art pieces but enough remain to give a hint of the once gay colours and resplendent forms.

So far, this is the only instance of “jian nian” mosaic sculptures found in Bukit Brown. With so many tombs unexplored there may be more surprises in store.

Recent Comments