Researched by Ang Yik Han

Died in the year of the Horse, 19 July 1942 and survived by one son named Kah Bo (嘉謀), Hou Xiu Xi ( 侯秀西 )located at Hill 1 was said to be a good orator and a staunch supporter of the China Relief Fund led by Tan Kah Kee.

He spoke at public rallies and occasions such as temple celebrations to exhort the local Chinese to support the anti-Japanese cause. According to an account, he was beaten to death during the Japanese Occupation for refusing to cooperate with the Japanese authorities.

Today marks the 70th anniversary of Lim Bo Seng’s martyrdom (29 Jun 1944)

An excerpt from Singapore war hero Lim Bo Seng’s diary:

“My duty and honour will not permit me to look back. Every day, tens of thousands are dying for their countries. You must not grieve for me. On the other hand, you should take pride in my sacrifice and devote yourself to the upbringing of the children. Tell them what happened to me and direct them along my footsteps.”

Family members attended a remembrance ceremony organised by Changi Museum, at the Kranji War Cemetery this morning.

Read the Today report here

Tan Ean Teck (1902-1944)

According to “Biographies of Famous Personalities in the Nanyang,” Tan Ean Teck came to Singapore from Tong Ann, China at the age of 16. He worked for about four years in his brother’s (Tan Ean Kiam) company before striking out on his own, setting up his own rubber trading firm.

He was a strong supporter of the anti-Japanese war effort in China, and contributed to charitable causes in both China and other lands. He also contributed to the Hokkien Huay Kuan, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the Tong Ann District Guild, as well as many schools and social institutions,

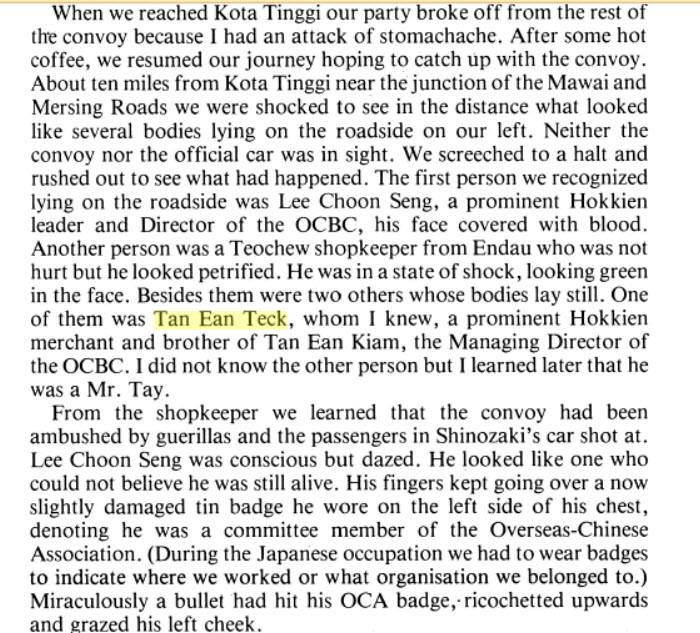

But Tan Ean Teck’s life was tragically gunned down when he became a casualty of WW 2. On 19 April, 1944, the MPAJA (Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army) ambushed officials of the OCA ( Overseas Chinese Association) en route to visit the Chinese settlement of Endau in Johor.

A member of the OCA convoy, captures vividly what happened:

Tan Ean Teck’s body was taken back to Singapore and 4 days later on 23ed April , he was buried in Bukit Brown, close to his brother Tan Ean Kiam. He was 42 years old.

Prologue: Endau and World War II

In August 1943, in order to ease the food shortage problem in Singapore, the Japanese authorities mooted the idea of setting up new settlements outside Singapore and encouraging Singaporeans to relocate to these settlements to cultivate the land there. These settlements were planned to become self-sufficient in food supply. A settlement was created for Chinese settlers at Endau in Johore. (Source: Iinfopedia)

From Alex Tan Tiong Hee

My understanding, based on my late father’s (Tan Yeok Seong) account:

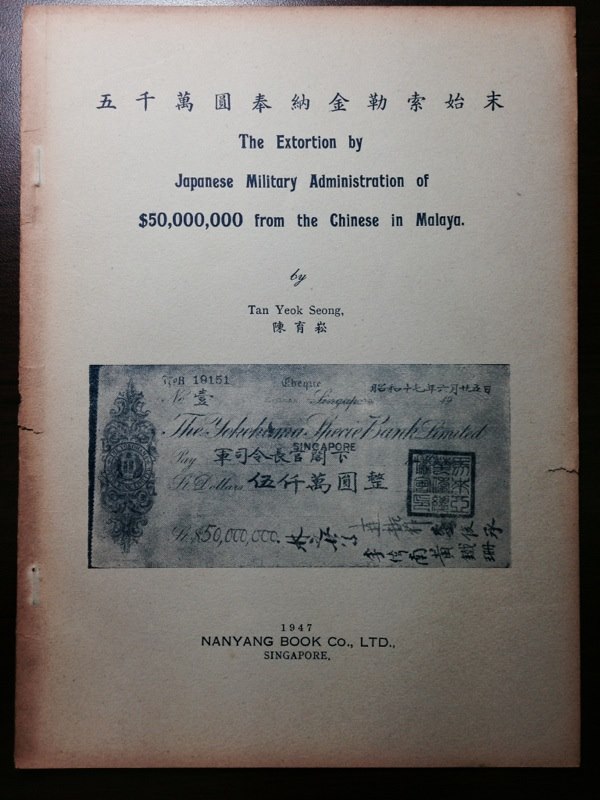

The OCA was not popular with the anti-Japanese elements that went underground to survive. Those living an open unconcealed life in public were natural targets for the Kempeitai who sought revenge against the Chinese, hence the pogrom.

The pacification of Japanese antagonism was the OCA’s raison d’etre and which had to be traded by the raising of $50million from the Chinese community as a gift for the Japanese emperor’s approaching birthday. This being done, the persecution or ‘sook ching’ then ended.

The communist terrorists were enterprising enough to merge with the anti-Japanese underground group to form the MPAJA. They accused the OCA as collaborators and monitored the Endau Project. Their opportunity came when they ambushed and fired at a convoy killing all except Lee Choon Seng who was Vice President of the OCA.

Extract from Collaboration during the Japanese Occupation : Issues and Problems focusing on the Chinese Community by Han Ming Guang (Hons thesis for history):

Even though Endau was administered by the Chinese, the fact that it was sponsored by the Japanese military and established by the O.C.A whom the MPAJA saw as an organisation of collaborators, meant that the Chinese administrators that administered the settlement were now targets for the MPAJA guerrillas. The MPAJA guerrillas ambushed the O.C.A officials that were on their way to visit Endau and in the process wounded Mr Lee Choon Seng, the chairman of the Overseas Banking Corporation. They also managed to kill Mr Wong Tatt Seng, who was in-charge of maintaining peace and order within the settlement, along with other Chinese administrators who were also living in Endau at the time of the attacks.

While it was clear that the MPAJA viewed the members of the O.C.A as well as the Chinese leaders of Endau as collaborators and traitors, in general the people who were living in Endau did not share those views. They understood that the Endau plan was conceived by the O.C.A and Mamoru Shinozaki in order to save Chinese lives from the dreaded Kempeitai , by giving the Chinese community a piece of land in Johore, for them to live separately and free from the Japanese military.

Pat Lin on life in Endau:

According to my parents, Maggie Lim and Lim Hong Bee (H.B. Lim) both of whom were actively involved with the MPAJA in the Endau settlement (Yes, I was there too) there were people in the OCA who were what we may today call double agents. They included some very prominent local people who on the surface professed to be anti-Japanese, but who were informers who were usually rewarded by the Japanese.

As with the French resistance, it was a very difficult time as people all lived under a climate of uncertainty as to who was about to betray them to the Japanese. My mother also had her suspicions as to those who carried out the covert assassination of informers.

She has a vivid story of having to deal with someone who was brought into the Endau clinic (she was the Endau doctor) one evening with a bullet in his head. As a physician she was duty bound to do everything to save him. She was filled with the reluctance to do anything as it was known by the Endau leadership that he fed information to the Japanese that led to people being taken away for execution or disappearing suddenly. Possession of any sort of weapons was punishable by death, but people like my father possessed hand guns that they somehow received from some source and were very carefully hidden.

Endau was located in healthier environs and there were more people who managed to make a go of farming. The staples were kangkong and ubi kayu. My little family brought chickens up from Singapore piled up In chicken coops on top of a lorry. Some of them ran off into the jungle, and others fell prey to wild animals. Wild animals including roaming tigers were a real threat.

The first year in Endau and Bahau were particularly bad before the first harvests. OCA members from Singapore would make periodic visits with whatever they could scrounge up including medicines. Some within the community tried being entrepreneurial by trying to sell black market food stuffs they somehow managed to obtain. Mom recalled being so hungry from having to work and nurse me but my father being ever the man of high ethical standards refused to allow the purchasing of black market goods.

An Epilogue on a Life Miraculously Saved

The metal badge of the OSA worn on the chest, deflected the bullet that could have fatally wounded the Vice President of the OSA, Lee Choon Seng. He believed he was saved for a reason and his life took on a spiritual quest in the aftermath of war. Lee Choon Seng subsequently founded the Poh Ern Shih to dedicate merits to people killed during the occupation. His grandson transfromed the monastery into Singapore’s first green temple.

***********

Editor’s Acknowledgement : This blog post is a compilation of first hand accounts and research from the Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown Facebook Community.

This chronology of the Japanese invasion was compiled by James Tann, a heritage blogger, in the lead up to the 72nd anniversary of the fall of Singapore on 15 February, 1942.

Feb 8, 1942.

The Japanese Army invasion of Singapore Island begins with the crossing at Lim Chu Kang.

February 9, 1942.

Having landed the night before along the Lim Chu Kang coast, by the afternoon of 9th Feb, Tengah Airfield was in the hands of the invading Japanese Imperial Army.

Also on 9 Feb, the Japanese Army opened a 2nd battle front by landing the Imperial Guards Division at Kranji and the Causeway. This Division was to move east heading towards the Sembawang & Thomson regions.

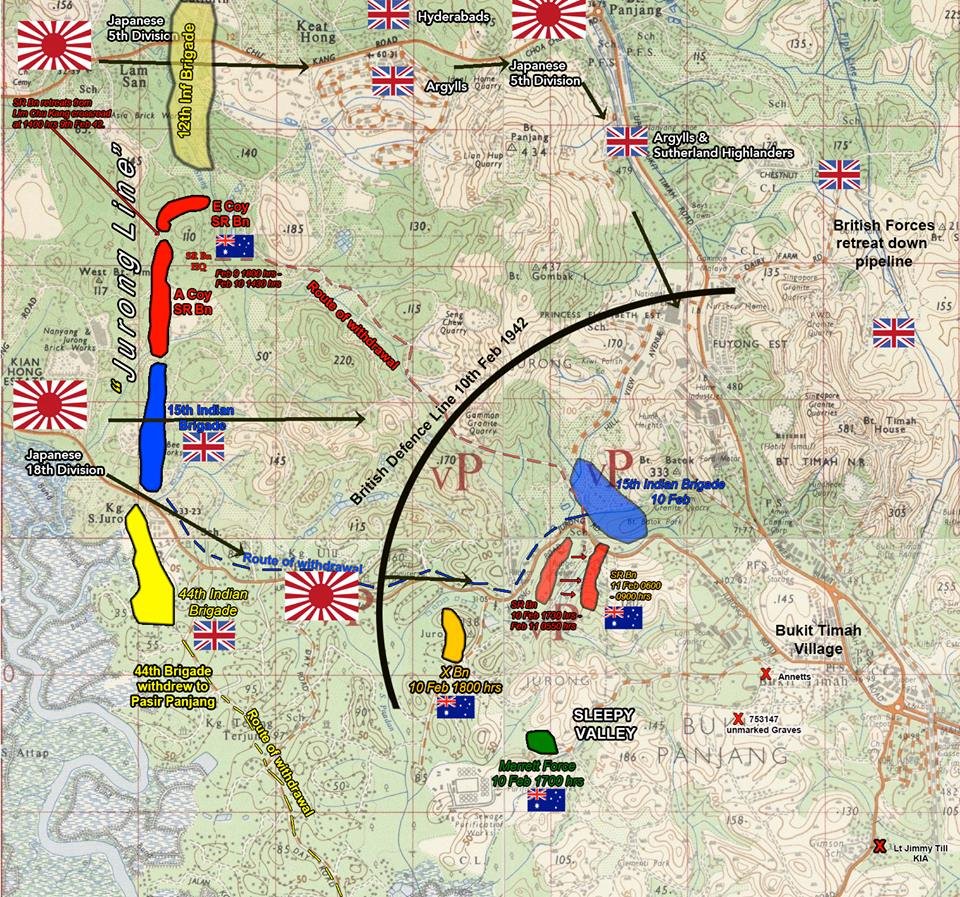

The Jurong-Kranji Line – 9th February, 1942.

The Allied forces formed a futile blockade called the ‘Jurong Line’ stretching east of Tengah Airfield, through Bulim to the Jurong River (where Chinese Garden is today) to try and contain the Japanese forces within the western sector of Singapore.

By evening of 9th Feb 1942, the Jurong Line had collapsed completely due to miscommunication. The main Australian 22nd Brigade retreated, resulting in a domino effect leading other units to retreat as well.

Luckily for them, the Japanese forces did not press their advantage as they had to wait for reinforcements and logistic supplies to follow up across the Straits to continue the invasion.

You can also read how a jungle dirt track saved the lives of 400 soldiers by James Tann here

10th Feb 1942.

The capture of Bukit Panjang and the massacre at Bukit Batok.

With the overnight collapse of the ‘Jurong Line’ blockade, the Japanese 5th Division easily manoeuvred down Choa Chu Kang Road and overpowered the defences by the Argylls & Sutherland Highlanders and the Hyderabad Regiment at Keat Hong. Pushing them back all the way to Bukit Panjang Village. It was the first encounter with Japanese tanks in Singapore by the British.

By the early afternoon, Bukit Panjang Village had fallen to the Japanese. Some British units managed to escape through the farmlands of Cheng Hwa and eventually followed the water pipeline down to British lines near the Turf Club region.

Intending to re-establish the ‘Jurong Line’, the British High Command despatched 2 battalions from Ulu Pandan to Bukit Batok (West Bukit Timah).

X Battalion made it way to 9ms Jurong Road (opp today’s Bukit View Sec Sch), while Merret Force lost its way and camped at Hill 85 (Toh Guan Road today).

The Japanese 18th Div coming down Jurong Road encountered both X Battalion and Merret Force during the night. X Bn, caught totally off guard, was annihilated and lost over 280 men, while Merret Force had half its force killed in the ambush.

The Japanese Commander, Gen Yamashita, had ordered both his 5th and 18th Division to take Bukit Timah Village and Bukit Timah Hill by the 11th Feb. Thus, both units were in a frenzied rush to capture the strategic high point.

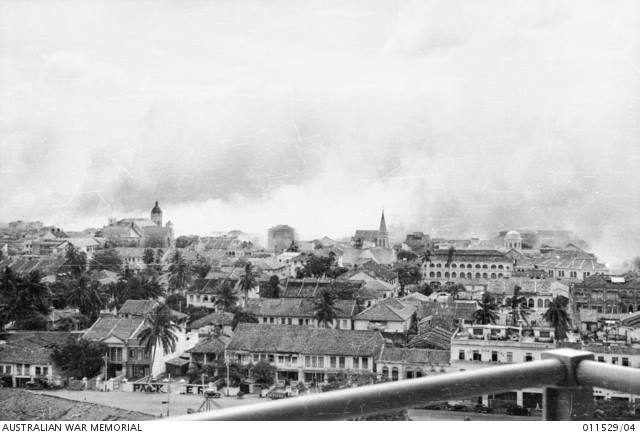

By midnight of 10th Feb, Bukit Timah Village was ablaze and effectively conquered by the invasion force.

Photo credits: Australian War Memorial

1. Japanese soldiers at Bukit Timah Hill

2. Japanese Type 95 HaGo Light Tanks in Bukit Timah Village

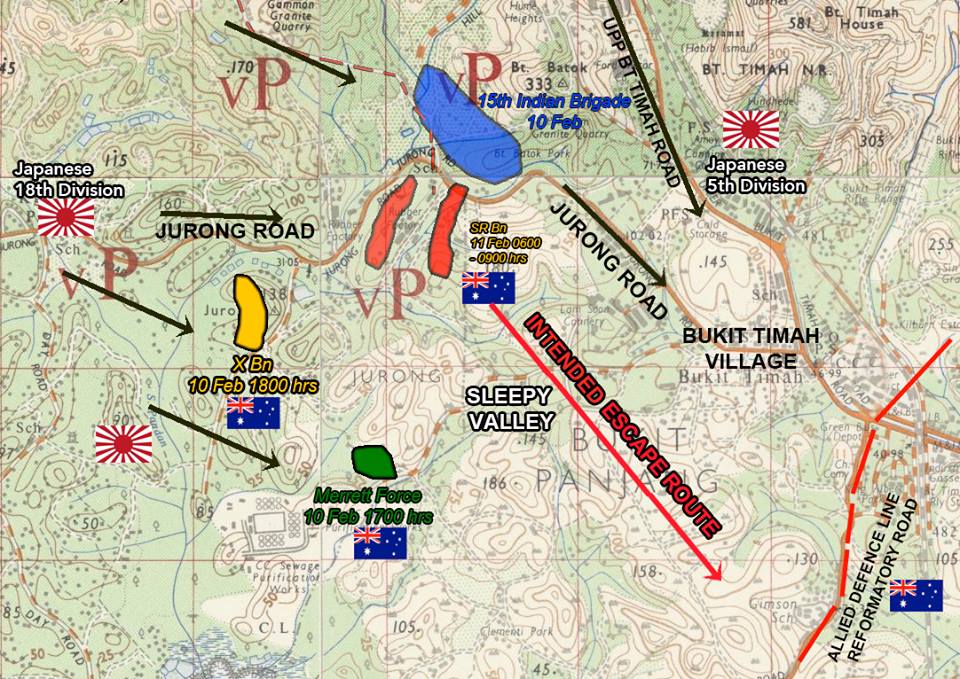

11th February 1942.

The Fall of Bukit Timah Hill and the Tragedy at Sleepy Valley.

By the time Gen.Yamashita’s army crossed into Singapore, he was critically short of supplies, fuel, ammunition and even food for his troops. His strategy was thus to conduct a tropical blitzkrieg – ‘hit them fast hit them hard’ – to capture Bukit Timah. It being the high point for observation also held the British ammunition, food and fuel depots which he coveted.

To raise morale of his troops, he set Feb 11 as the day to capture Bukit Timah Hill. The significance of Feb 11 was that it was the Japanese Kigensetsu, the day they celebrate the ascension of the 1st Emperor and the founding of the Japanese Empire. The task was assigned to competing 5th and 18th Divisions with untold glory going to the unit achieving the objective first.

By midnight of 10th Feb, both units had already reached Bukit Timah Village and the resultant battle against the British defenders set the entire region ablaze. The British retreated and held their line at Reformatory Road (Clementi Road)

By early morning of the 11th, the Japanese had secured Bukit Timah Hill.

Meanwhile back at Bukit Batok…

By the morning of 11 Feb, the senior commander of 15th Brigade, Brigadier Coates, who was to lead the re-taking of the Jurong Line, knew that the Japanese had surrounded his position. He cancelled the order and proceeded to retreat, together with the Special Reserve Battalion, back to allied lines at Ulu Pandan.

Forming 3 columns consisting of 1500 men from the British, Indian and Australian units, they proceeded from Bukit Batok to cross an area called Sleepy Valley.

Unknown to them, the Japanese 18th Division was already waiting to spring their trap on the British soldiers.

What happened next is a seldom mentioned debacle which actually had the highest number of casualties of any skirmish within Singapore during the war. The firefight that took place at Sleepy Valley took the lives of 1100 allied soldiers out of the 1500 who entered that valley of death.

Throughout the day, the British sent in reinforcements to try and re-take Bukit Timah. However, both Tomforce and Massey Force could do little to dislodge the Japanese.

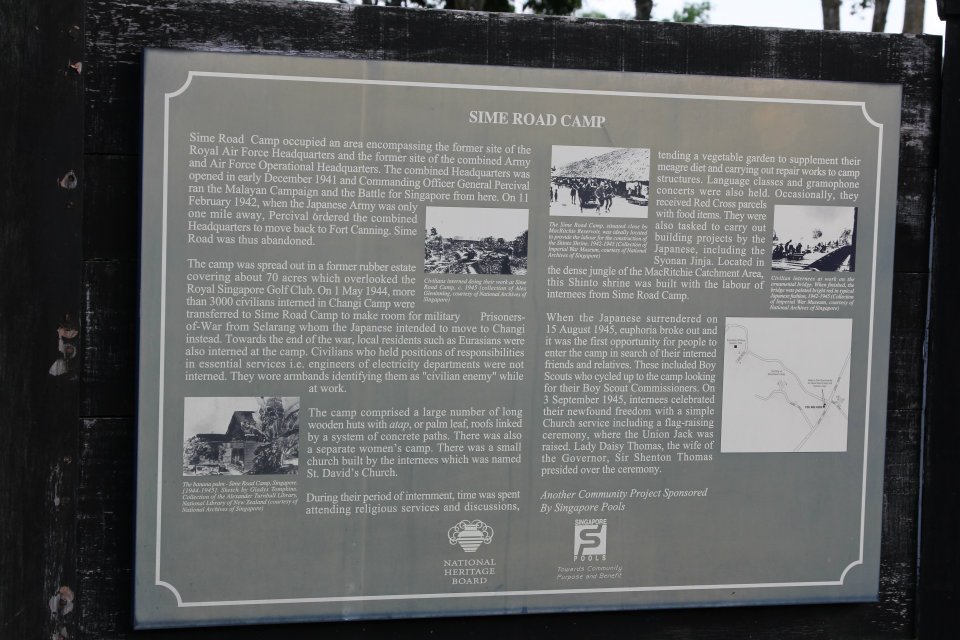

When Bukit Timah Hill fell, Gen Percival moved his HQ from Sime Road to Fort Canning. The fear of the approaching Japanese Army also led them to destroy the infamous 15” Guns at Buona Vista Camp at Ulu Pandan that morning. It was a sign that things had come to bear…

12th Feb 1942.

Yamashita’s Ultimatum.

Tomforce’s attempt to re-take Bukit Timah and Bukti Panjang ended in futility. Unknown to them, they were up against the battle hardened Japanese 56th and 114th Regiments of the 18th IJA Division, Yamashita’s crack troops, who had fought all the way from China.

By the morning of 12th Feb, the British lines were being pushed backed.

Tomforce fell back from Reformatory (Clementi) Road to Racecourse when the Japanese overran the supply depots at Rifle Range. By the end of the day they would retreat all the way back to Adam and Farrer Road.

By then, Gen Percival had redrawn the defence line.

Massey Force would protect the waterworks from Thomson Village to the east of the MacRitchie golf links, where the former HQ at Sime Road was.

Gen Heath’s British units would fall back from Nee Soon, having abandoned the Naval Base, and form the line from Braddell to Kallang.

In the west, the Australians fell back from Reformatory Road to Holland Road (Old Holland Road), while the 44th Indian Brigade formed the line from Ulu Pandan to Pasir Panjang. Sporadic fighting occurred throughout the day along the line.

Elated with the capture of Bukit Timah, Gen.Yamashita was still faced with logistical problems including a critical shortage of ammunition. He knew he wouldn’t be able to last out in a war of attrition and thus resorted to his plan to bluff the British into surrendering, by dropping ultimatum notes into the British lines.

“To the High Command of the British Army, Singapore”

I, the High Command of the Nippon Army have the honour of presenting this note to Your Excellency advising you to surrender the whole force in Malaya.

My sincere respect is due to your army…bravely defending Singapore which now stands isolated and unaided…..futile resistance would only serve to inflict direct harm and injuries to thousands of non-combatants….Give up this meaningless and desperate resistance…If Your Excellency should neglect my advice, I shall be obliged, though reluctantly from humanitarian considerations to order my army to make annihilating attacks..”

(signed) Tomoyuki Yamashita”

Getting no response to his ultimatum message, Yamashita sent his units on probing incursions along the line.

These took place mainly at Sime Road and Pasir Panjang near Normanton.

He had no intention to enter the city as he knew he did not have the resources to fight a street to street battle.

Major Bert Saggers was CO of the Special Reserve Bn that was ambushed at Sleepy Valley. He survived and made his way to Ulu Pandan where he found only 80 of his 420 men alive but all his officers killed. (photo Ian Saggers, Perth Australia )

Lt Jimmy Till was an officer in Bert Sagger’s unit. He was buried near the spot where he was killed. This was near where today’s Ngee Ann Polytechnic Alumni Clubhouse stands. Picture is his grave now at Kranji War Memorial. (photo James Tann)

13th Feb 1942.

The noose tightens around Singapore City.

With the core of Singapore Island firmly in the hands of the Japanese Army, Gen.Yamashita moved his HQ from Tengah to the Ford Motors factory at Bukit Timah.

Strangely, the previous day ended somewhat with a lull in the fighting.

This allowed Gen Percival to continue finalising his last line of defence.

From Kallang Airfield to Paya Lebar, Paya Lebar to Braddell, Thomson Village to Adam Park, Adam Road to Farrer Road to Tanglin Halt, from Buona Vista across Pasir Panjang ending at Pasir Panjang Village.

The last unit to pull out , the 53rd Brigade, left Ang Mo Kio area around noon and the traffic along Thomson Road was so choked that Japanese planes had an easy time strafing the columns along the route.

Gen.Yamashita had actually feared that Gen.Percival would dig in and fight to the last.

In order to continue his feint, despite running low on ammunition and men, he launched attacks to give the British the appearance of Japanese strength.

He ordered the crack 18th Division to take Alexandra Barracks and the 5th Div & the Imperial Guards to attack the Waterworks at MacRitchie and the pumping station at Woodleigh.

Alexandra Barracks was the main British Army Ordnance Depot, where most of their equipment, stores and fuel storage, as well as the main Alexandra Military Hospital, were located

The attack on Alexandra Barracks began from Pasir Panjang (Kent Ridge) after 2 hours of heavy shelling at noon.

Waves of Japanese soldiers fought determined defenders from the 1st Malaya Brigade and the 44th Indian Brigade. Fighting was vicious and often hand to hand. The Malay Regiments were slowly overpowered with the Japanese winning height after height. The Gap, Pasir Panjang Hill III, Opium Hill, Buona Vista Hill, would fall one after the other but fighting would continue till the following day.

Over at MacRitchie, the Japanese 5th Division fought the 55th Brigade (1 Cambridgeshire & 4 Suffolk Regiments) to gain control of the reservoir. An all night tough fight including tanks forced the British Regiments all the way back to Mount Pleasant Road across Bukit Brown cemetery. The Suffolks lost over 250 men defending their ground.

The Japanese Army was now within 5 kilometres of the City on 2 fronts.

All this while, civilians casualties were mounting in the collateral damage from the Japanese shelling.

The City now had up to 1 million evacuees, most in dire straits without shelter, food nor water.

An Officer was to record travelling down Orchard Road:

“Buildings on both side went up in smoke…civilians appeared through clouds of debris; some got on the road, others stumbled and dropped in their tracks, others shrieked as they ran for safety. We pulled up near a building which had collapsed, it looked like a slaughter house; blood splashed, chunks of human being littered the place. Everywhere bits of steaming flesh, smouldering rags, clouds of dust and the groans of those who still survived.”

At the Battlebox, the new HQ at Fort Canning, Gen.Percival and his senior commanders were contemplating the latest orders from Gen.Wavell as well as an order from Churchill.

14th Feb 1942.

Prelude to Capitulation

Throughout the night of 13/14th Feb, sporadic skirmishes occurred both at Pasir Panjang and Adam Road.

At daylight 8.30am at Pasir Panjang Ridge , the Japanese charged up for a final assault on Hill 226 and Opium Hill facing heavy resistance from the 1st Malay Regiment. Bitter hand to hand combat lasted till 1.00pm in the afternoon when the Japanese gained control of the hills and in the process annihilating the Malay Regiment.

As the loss of the strategic ridge gave way, the Japanese advanced along Ayer Rajah in pursuit of Indian troops towards the British Military Hospital. It was then that the tragic incident occurred at the BMH with the senseless slaughter of wounded patients and medical staff.

There was also little relief along Adam Road. The Japanese, with Col Shimada’s Tank Regiment, pressured the line with a bulge through Bukit Brown, towards Caldecott Hill and Adam Park. Bitter fighting occurred around Hill 95 and Water Tower Hill (today’s Adam Park/Arcadia).

The Imperial Guards Division harried the eastern battle line at Paya Lebar and were near to capturing the Woodleigh pump station by mid day.

At British HQ in the BattleBox at Fort Canning, Gen.Percival conferred with his field commanders.

Brigadier Simson advised that the water situation was extremely grave with the threat of epidemic.

Gen Heath, commander of British Forces, and Gen Bennett, commander of Australian Forces, urged Gen Percival to surrender. Percival refused to yield, having direct orders from Churchill via Gen.Wavell, the Commander in Chief based at Java, not to surrender and to fight to the last man.

However, Gen.Percival informed Gen.Wavell that the enemy was close to the City and that his troops were no longer in a position to counter attack much longer.

Gen. Wavell sought permission from PM Churchill to allow Gen.Percival to consider the option of surrendering.

Churchill replied to Gen. Wavell:

“You are, of course, sole judge of the moment when no further result can be gained at Singapore., and should instruct Percival accordingly, C.I.G.S. concurs”

With that, the final key was inserted into play for Singapore. (But the permission for Percival to consider surrendering did not go out to Percival until the next morning of the 15th.)

*CIGS = Chief of Imperial General Staff

Lieutenant-General A E Percival, General Officer Commanding Malaya at the time of the Japanese attack.(photo Imperial War Museum London)

General Sir Archibald Wavell, C-in-C Far East, and Major General F K Simmons, GOC Singapore Fortress, inspecting soldiers of the 2nd Gordon Highlanders, Singapore, 3 November 1941. (photo Imperial War Museum London)

15th Feb 1942.

Chinese New Year – The Year of the Horse

There was absolutely no joy in celebrating Chinese New Year in 1942. The country was in shambles.

The foreboding fear of the encroaching Japanese military, preceeded by tales and rumours of their atrocities in China all portent the unknown that lay ahead.The British masters and their families had all bugged out. What did this mean for the locals now?

A Japanese flag could he seen flying from the top of the Cathay Building! Was this the end?

For the locals, especially for the Chinese, it was going to be the start of three and a half horrifying years.

Morning of 15th Feb saw the opposing forces holding most of their ground, with infiltration mainly by the Japanese within the eastern sector reaching Kallang Airfield. In the west, Japanese troops reached Mount Faber.

Gen. Percival convened his most senior officers at the Battlebox at 9.30am for the latest status reports.

Brigadier Simson reported that water supply could not be maintained for more than a day due to breakages everywhere which could not be repaired. Water was still flowing despite the pumps and reservoir being in enemy’s hands!

The only fuel left were what remained in each vehicle and at a small pump at the Polo Club.

Reserved military rations could last for only a few more days.

With unanimous concurrence of all present, the decision to cease hostilities and to capitulate was made.

A deputation comprising Brigadier Newbigging, HQ Chief Admin Officer, the Colonial Secretary Mr Fraser and Major CH Wild as interpreter, left Fort Canning for the enemy lines at Bukit Timah Road.

At the junction of Farrer Road, they proceeded on foot with Union Flag and a white flag across the defence line for 600 yards where they were met by the Japanese soldiers. They were later met by Col Sugita who refused their ‘invitation’ to the City for negotiations. Instead, Col Sugita demanded that Gen.Percival was to personally surrender to Gen.Yamashita.

To acknowledge this condition, the British were to fly a Japanese Flag from the top of the Cathay Building.

At 5.15pm, the British surrender party drove up to the Bukit Timah Ford Motors factory.

The delegation was made up of Lt-Gen AE Percival, Brigadier Newbigging, Brigadier Torrance, Gen Staff Officer Malaya Command, and Major Wild, the interpreter from III Corps.

Though Gen.Percival tried to negotiate for some terms for his men, Gen Yamashita thought that he was playing for time and pressed Percival for an unconditional surrender, telling him that a major attack on the City was scheduled for 10.30pm that night and any delay, he might not be able to call off the operation in time.

“The time for the night attack is drawing near! Is the British Army going to surrender or not?”

Banging the table he shouted in English “Answer YES or NO.”

At 6.10 pm. Gen.Percival signed the surrender document, handing Singapore over to the Japanese Empire.

************************

Read about the Battle at Bukit Brown on 14 February, 1942, a day before the surrender to the Japanese, here

And the latest on missing soldiers here

Time 9 am – 12 pm

MEETING POINT: Junction of Lorong Halwa, Kheam Hock Road and Sime Road.

Feb 15, 1942 – Singapore, the “Impregnable Fortress” of the British Empire, falls to the Japanese invading forces.

Visit Bukit Brown Cemetery, site of fierce battles involving British (4th Suffolks) and Indian (Royal Deccan Horses) forces, near a village of Chinese and Malay civilians had lived.

Your guides are Claire and Ish Singh, and Peter Pak. Together they will help piece together an important day in Singapore history at the site, and recount personal stories of those buried there as well as an account of their families got caught up in the war. We welcome anyone with knowledge of the area and the battles fought there to join us and honour the memory of the war dead.

Disclaimer: By agreeing to take this walking tour of Bukit Brown Cemetery, I understand and accept that I must be physically fit and able to do so.To the extent permissible by law, I agree to assume any and all risk of injury or bodily harm to myself and persons in my care (including child or ward)

Registration:

Please click ‘Join’ on the FB event page to let us know you are coming, how many pax are turning up, or just meet us at the starting point at 9am.

“We guide rain or shine or exhumations.” – we urge you to wear sensible shoes, carry a bottle of water, put on insect repellent, and come with an open mind as we explore together. We share and talk as we walk, and learn from each other. Our walking tours are meant to be learning journeys, for both participants and guides. We believe in building communities and growing organically.

** IMPORTANT NOTE: GETTING THERE: http://bukitbrown.com/

Reading materials:

This was their last tour report, marking the day bombs first fell on Singapore: http://bukitbrown.com/

To read about the 4th Suffolks battling the Japanese who came across Hellfire Corner on the evening of Feb 14, 1942: http://bukitbrown.com/

To read about the Kheam Hock skirmish and massacre: http://bukitbrown.com/

Bukit Brown is the only Singapore site on the World Monuments Fund Watch List of threatened heritage sites. Read more here: http://bukitbrown.com/

Ish himself found a strong link to his Sikh roots through Bukit Brown: http://bukitbrown.com/

Claire’s TEDx talk touches on the war: http://www.youtube.com/

all things Bukit Brown will mark the weekend with tours and talks on both days. Keep an eye for updates.

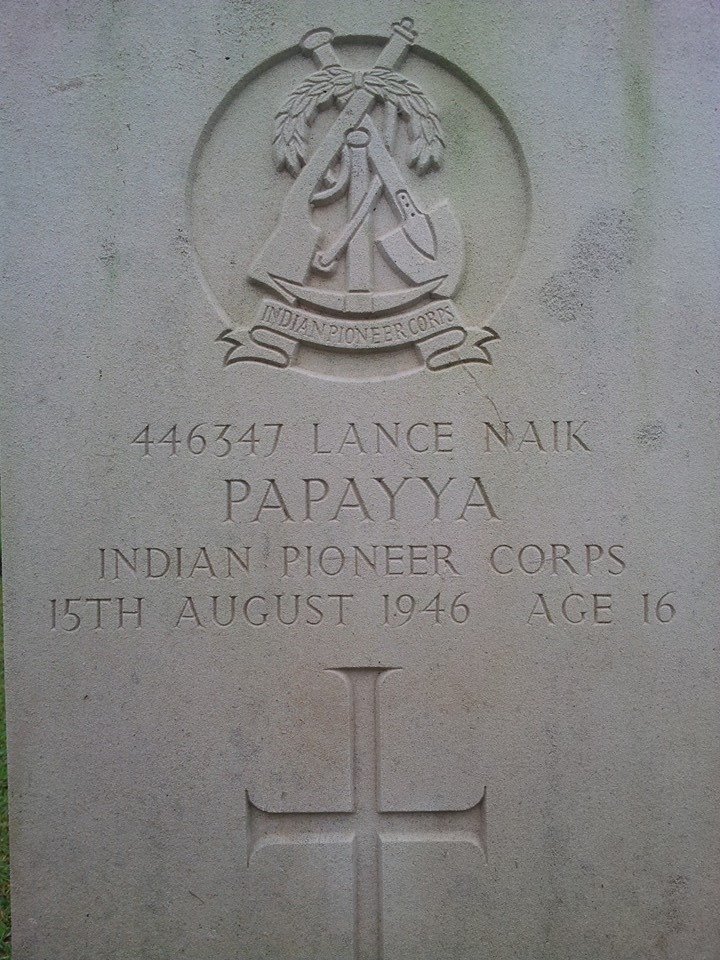

Dateline Sunday 10 November, Kranji War Memorial.

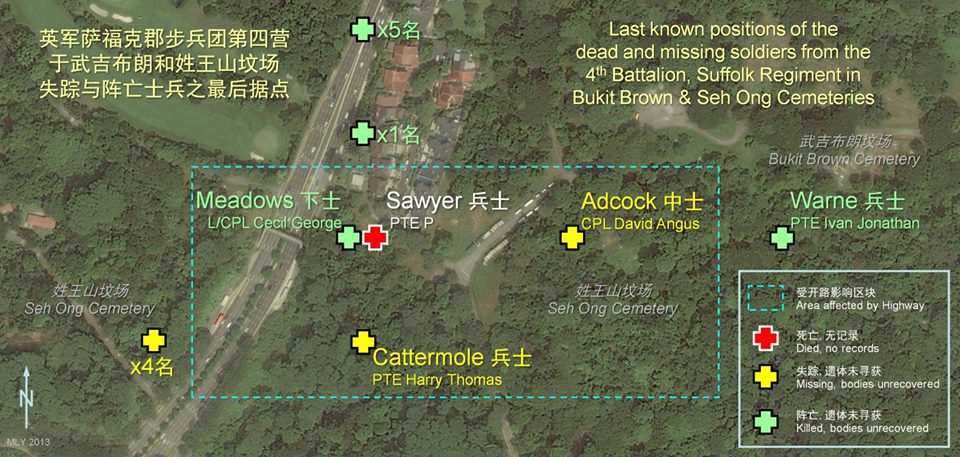

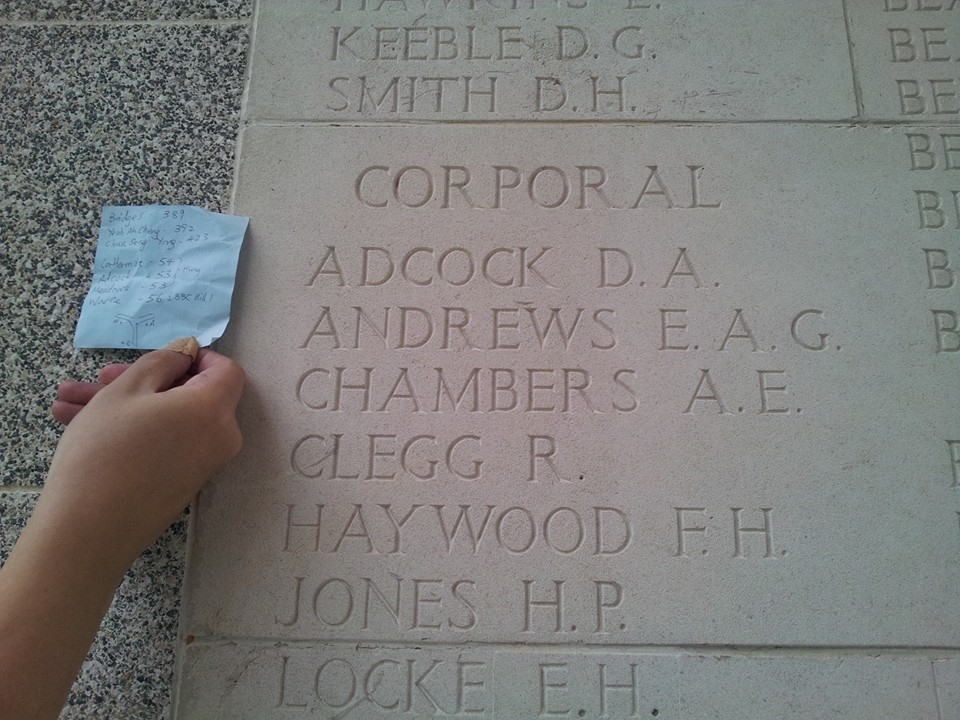

Remembrance Day was commemorated at the Kranji War Memorial in a ceremony dedicated to those who died fighting for Singapore during World War II. Brownies Khoo Ee Hoon and Mok Ly Yng who attended the memorial service had another mission when they were there, to seek out the names of 5 soldiers who had been listed as missing in the Battle at Cemetery Hill (Seh Ong and Bukit Brown Cemeteries).

Based on war records, Ly Yng had already mapped out the dead and missing soldiers from the 4th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment, whose last known positions are right in the middle of the proposed 8-lane highway cutting across Seh Ong and Bukit Brown Cemeteries.

The 5 soldiers, named are not the only ones fallen in the battle.

“4x in yellow to the left of the green box represents 4 individuals known to be buried at that position. At the top of the bo along Lornie Road are know to be 5 soldiers (5x), as with the 1x (in green) at the Lornie Road houses. As these soldiers were located outside of the immediate threatened area, I did not include their names, so as to reduce map clutter.But I decided to keep them in the map to provide some context and indicate that there are in fact more soldiers around the area within the Greater BB area.” Mok Ly Yng.

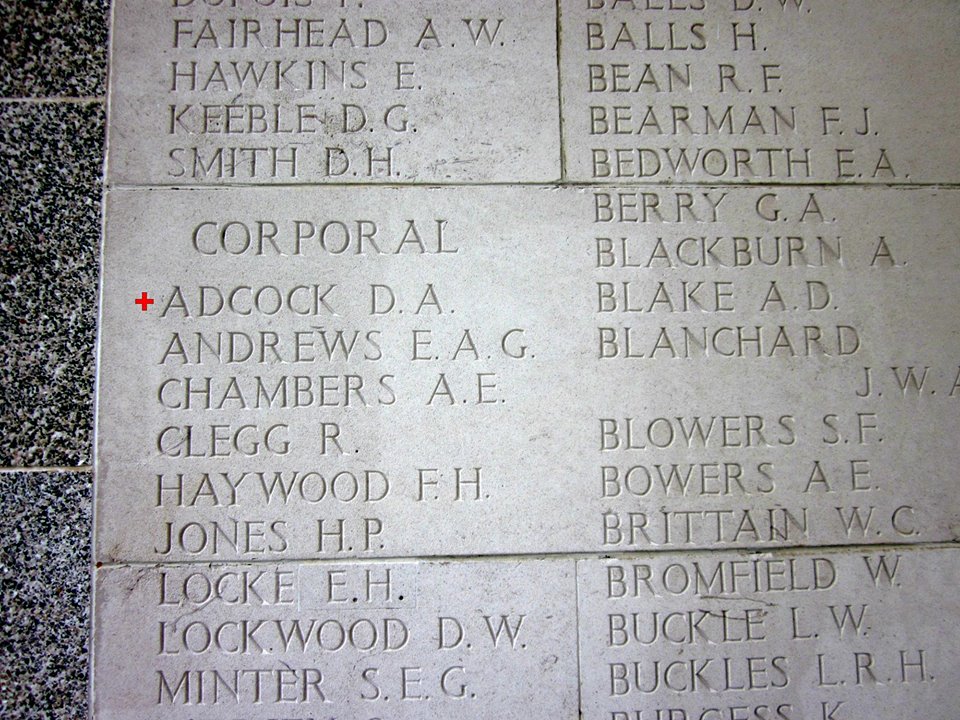

At the Kranji War Memorial, the soldiers’ names on the memorial wall :

Corporal Davis Angus Adcock

Singapore Memorial Column 53, Kranji War Memorial

Missing: 12 Feb 1942

Lance Corporal Cecil George Meadows

Singapore Memorial Column 53, Kranji War Memorial

Killed: 14 Feb 1942

———-

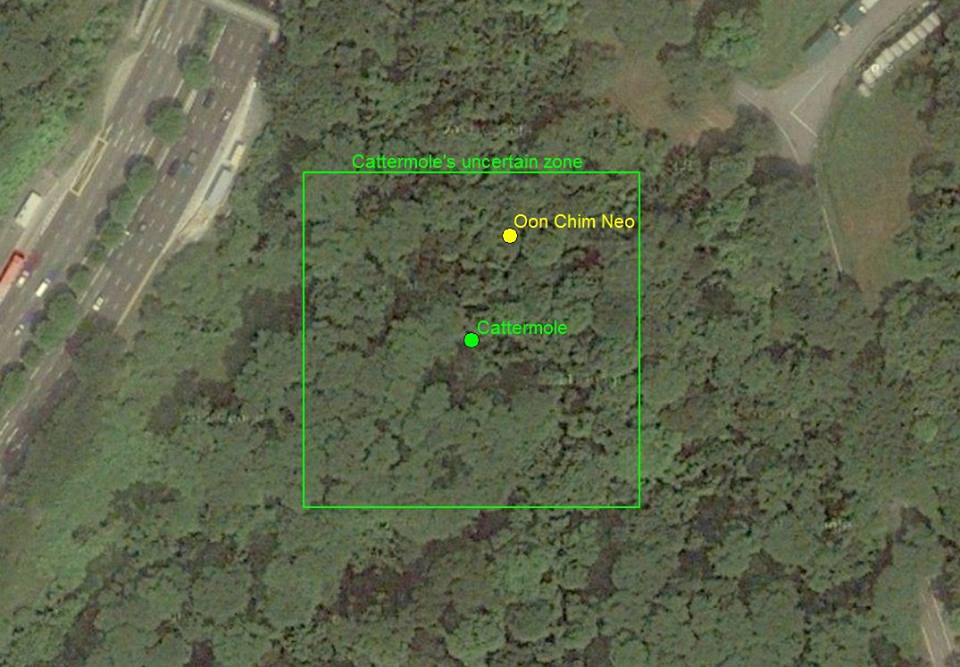

Private Harry Thomas Cattermole

Singapore Memorial Column 54, Kranji War Memorial

Missing: 14 Feb 1942

Missing. Last seen on Hill 95, badly wounded on 14 Feb 1942.

Mok Ly Yng clarification of Cattermole’s position: “Due to the large map coordinate error, Cattermole could be buried within 50 m of the map coordinate’s position. in other words, he could be very, very to Oon Chim Neo’s grave too. In fact the uncertainty area overlaps her grave. “

Private Ivan Jonathan Warne

Singapore Memorial Column 56, Kranji War Memorial

Killed: 14 Feb 1942

Buried top of Highest hill Chinese Cemetery East of Adam Road in Adam Road – Lornie Road Area by padre Polain 2/26 Bn AIF 14.2.42 (crossed out May 1942) Effects 2 Identity Discs, 1 cross.

Private Ivan Jonathan Warne’s position is not affected by the road construction. He is listed as the only known unrecovered casualty to be buried in Bukit Brown Municipal Cemetery proper (Hill 1).

Mok Ly Yng on the case of Private P Sawyer in the map:

“The 5 named individuals on the map were known to have been killed or last seen at those map coordinates just before or after the surrender. But after the war, those who were recorded as’ buried’ could *not* be found again and their remains are still missing. Private P Sawyer is the most difficult to find. His records showed that he had ‘Died in Singapore’ on 14 Feb 1942 and that he was buried on 17 Feb 1942 but this burial record was crossed out at a later unknown date. This leaves him with no records and hence he does not appear on the Singapore Memorial at Kranji nor the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s (CWGC) database or nominal roll, unlike the other 4 named soldiers presented here.”

In battle, the Cambridgeshire Regiment and the Suffolk Regiment fought in adjacent sectors. The Cambridgeshire Regiment held the Adam Park area while the Suffolk Regiment the Bukit Brown Cemetery area. In death, casualties of the two regiments are buried in adjacent sections at Kranji. This photo shows the boundary between the Cambridgeshire Regiment and the Suffolk Regiment in Kranji.

Kranji War Memorial Sunday 10 November, 2013. Cambridgeshire and Suffolk regiments (photo Mok My Yng)

From Jon Cooper. historian and war archeologist on the Adam Park Project, who also conducts the Battlefield Tour at Cemetery Hill once at month at Bukit Brown:

‘The fate of the missing Suffolks on Bukit Brown is just part of the rich WW2 heritage that can be found on the hills. There were many other units fighting in the area, constantly passing over the cemetery during the ebb and flow of warfare. It is most likely that there are more missing men to be found amongst the headstones.

There will also undoubtedly be spent ammunition and equipment to be found across the site, the remnants of fieldworks and bomb craters and the general detritus of war. Each item will be the part of a big jigsaw of artifacts and by plotting the locations in the landscape it will be possible to gather invaluable information about fighting that took place there.

The impending work on the hills will peel back the top layers and will undoubtedly expose these traces of the past.Hopefully the construction teams, with proper instruction will identify these clues and call in the experts to catalog and retrieve the material before the concrete is poured over it. There is a chance; just one chance to collect this invaluable evidence.

But most of all there is the possibility that we may come across the remains of our missing men. A chance to identify them and lay them to peaceful rest amongst their own. The fact that we go to great lengths to retrieve these men says as much perhaps about the attitude of Singaporeans today as it does about their generation of sacrifice.’

Jon Cooper and Mok Ly Yng who are working together to identify locations of the fallen Suffolk soldiers (photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

Mok Ly Yng at the memorial wall looking for the names of the fallen in the Battle on Cemetery Hill ( photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

The Suffolk Regiment casualties list on the Singapore Memorial at the Kranji War Memorial, columns 53 & 54. (photo Mok Ly Yng)

Mok Ly Yng is part of the documentation team tasked by the government to record and document graves affected by the impending highway

The Kranji War Memorial is dedicated to the men and women from United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Sri Lanka, India, Malaya, the Netherlands and New Zealand who died defending Singapore and Malaya against the invading Japanese forces during World War II, it comprises the War Graves, the Memorial Walls, the State Cemetery, and the Military Graves.

Kranji War Memorial, Sunday 10 November 2013. A member of the Royal Air Force, which is Jon Cooper’s unit (photo Mok Ly Yng)

Kranji War Memorial, Sunday 10, November 2013. A member of the Royal Engineers, the unit responsible for mapping and map production (photo Mok Ly Yng)

Ubique Quo Fas Et Gloria Ducunt

Everywhere – Where Right and Glory Lead

by Grace Seah

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Maya Angelou

In memory of my Uncle Tan Kim Cheng

One might wonder what has WWII & Operation Sook Ching has to do with Bukit Brown as a place in our history.

Among the men, women and children buried at Bukit Brown were victims, killed by the Japanese during the war. Many lived through that tumultuous period in Singapore’s history and carried with them the pain and heartache of not knowing where their son or daughter went during the war, never to be seen again.

This is a story of one such family – my family.

In an earlier blogpost about my grandparents, I shared a much loved family photo which included my grandparents, my father and his 2 elder brothers. One of his brothers was taken by the Japanese that one fateful day in Operation Sook Ching and my grandparents never saw their third son ever again.

Just what was Operation Sook Ching ?

According to the heritagetrails.sg website

“A decree was issued on Wednesday 18 February 1942: All Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 in Syonan-To (as Singapore was called during the Japanese Occupation) were to report to the various registration centres around the island. The decree embodied Japanese hatred for the Chinese, cultivated through years of Sino-Japanese war since 1937. Also, overseas Chinese had been quickly labelled anti-Japanese due to their contributions to war efforts in China. Thus began the Sook Ching operation, or the elimination of anti-Japanese elements.”

A story that is often told in our family revolved around the time my father, Tan Kim Huat – youngest son of Tan Keng Kiat and Chan Gim Neo, – was rounded up by the Japanese, together with his third brother Tan Kim Cheng. Both were taken to a holding area with many other young Chinese males in the vicinity. They were not told of the reason for their detention, but they were all held like prisoners surrounded by fiercely guarded fences and barriers.

Many like my father experienced the sheer terror of not knowing what to expect from their captors that drove them to despair and desperation. Many never lived to tell their story. My father did.

On the night of their capture, my father had a premonition that all of them were going to be killed the next morning. He heard his inner voice telling him to run for his life and resolved to find a way out no matter what. At 22 years of age, my father possessed the courage and brashness of youth which stood him in good stead in this instance.

He sought out his elder brother and told him of his plan to escape. My uncle being of a different nature just could not find it in him to make that dangerous journey. My dad, not being able to convince his brother to follow suit, then decided to make a run for it in the middle of the night.

Whatever possessed my father to take that perilous journey, to this day, he cannot say. But with his every being pumped up with adrenalin, he did the unthinkable and scaled a secured fence and ran away to freedom, all the time expecting a bullet to his back.

Imagine my grandparents’ elation and at the same time heartache when my dad ran home that day but without his brother. The next morning, my aunts went to the place of detention to look for my uncle but never found him again. He was presumed dead, and I believe, his name is engraved amongst those of the many civilian war victims at the Civilian War Memorial near the Padang.

As for the young women, my mama (grandma) had to urgently find a couple of single men willing to take my unmarried aunties as wives at short notice so as to protect them from the Japanese. My aunts were married off to non Peranakans from humble backgrounds. Both my uncles ended up being good men who looked after my aunts and the children that followed as best as they could.

If my aunts had not been hurriedly married , they would most certainly have been taken by the Japanese to be comfort women. If my father had not been so brave, I would not be here today.

We must therefore never forget the courage and spirit of the people of Singapore during the early years. Their blood flows through us, because of them, we are here.

My father on the extreme left beside his mother (my grandma) and next to her my Uncle Tan Kim Cheng who was lost to Sook Ching ( Family Album )

by Catherine Lim

The tour on Sunday 22 July, starts off rather ignominiously atop a pedestrian bridge which spans a busy dual carriageway and ends with a touch of the macabre, sitting on tombstones under a shady tree.

Welcome to Jon Cooper’s Battlefield Tour of Cemetery Hill aka Bukit Brown Cemetery. The 2 hour tour’s main route takes you mostly along side the greens of one of Singapore’s most exclusive private golf course and club. As Jon paints a picture of the battleground -literally the blood sweat and tears – I gaze out at the golfers blissfully unaware the ground they are strolling was once a battlefield. But I am moving ahead of the tour here.

The view which sets the geographical location of the battleground, now imagine it wild and green (photo Bianca Polak)

Heritage marker which I reckon only gets a passing glance from bus commuters and joggers in the area ( photo Bianca Polak)

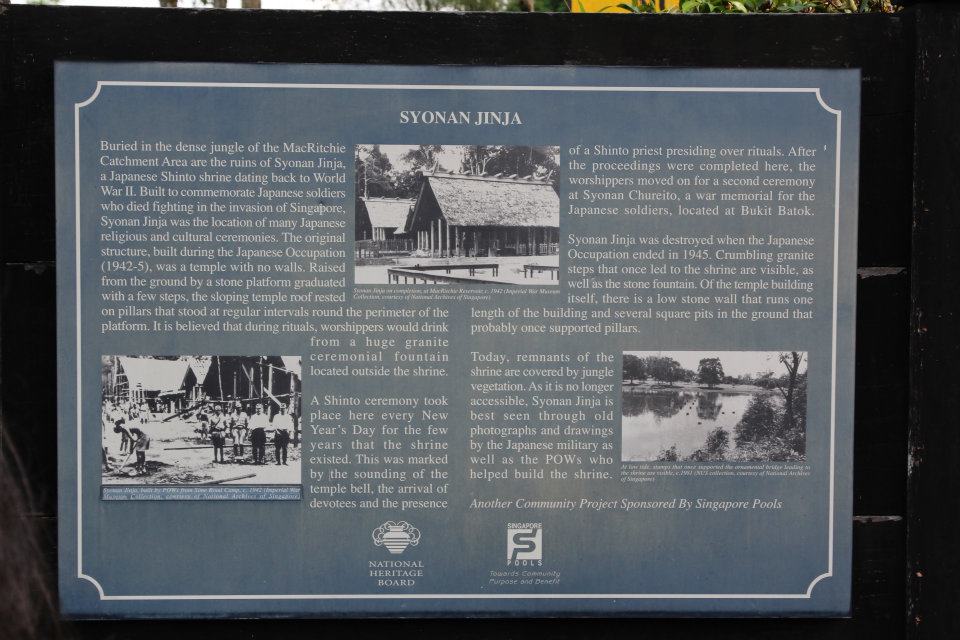

The Shinto Shrine which British POWs helped to build for the Japanese, traces of which are still at MacRitchie Reservoir but off limits to the public (photo Bianca Polak)

Turning into Sime Road SICC, on the left beyond the tall hedges Seh Ong Cemetery (photo Bianca Polak)

Much safer to walk on the soft greens as this mother and daughter team demonstrate (photo Claire Leow)

Third stop 64 Sime Road – The ideal Command House for the British before the war, but there not enough time to consolidate before the Japanese was upon the area (photo Bianca Polak)

Postscript : 64 Sime Road. Post-war building, known as ‘Air House’, official residence of the ‘Commanders-in-Chief and Commanders of the Far East Air Force from 1949 until November 1970’. Far East Air Force was FEAF (pronounced Fee-Eff). HQ FEAF was here in Singapore, the area of operations was from the east of Ceylon to the Solomon Islands in the Pacific, north to southern China and south to East Timor.

Under the shady tree outside number 64 Sime Road, Jon continues the story of brave men from both sides and the battle they faced (photo Claire Leow)

Jon’s most diligent student, he had already been on Jon’s Curator’s Tour of the Adam Road project which was held at the NLB (photo Claire Leow)

And the unexpected surprise of this tour, the caretaker on his own initiative decides we should be let into the ground of number 64 after observing we had been there for some 20 minutes ( photo Claire Leow)

An unexpected bonus for Jon as he is reunited with the insignia of his regiment top row (photo Claire Leow)

Inside, workers who have been maintaining the house, which we suspect will be up for rent soon (photo Claire Leow)

The Group photo, all thought this would make a marvelous war museum for Adam Park and wondered how much was the rent (photo Claire Leow)

As we continued to our fourth stop, from where we stood, we saw this idyllic scene (photo Bianca Polak)

It was here, a 100 metres opposite no, 64 (back on the road heading back to Lornie Rd) under the by now scorching sun that Jon showed us the lay of the land and the battleground ahead at Bukit Brown (photo Claire Leow)

Here is an extract of the battle on the evening of 14th Feb 1942 from an earlier post

The gunners’ targets were the men of the 4th Suffolks, a fresh-faced territorial battalion of the 18th Division who had only landed in Singapore two weeks earlier. The Suffolks, raised from the country towns and farming communities of East Anglia, had already seen combat up at Bukit Tinggi and had been forced to retreat back towards the Lornie Road by the relentless drive of the IJA’s elite 5th Division. The Suffolk’s hasty withdrawal and the stubborn defence of Adam Park by the 1st Battalion Cambridgeshires had allowed the men to establish new positions overlooking the eastern end of the SICC golf course and southern tributaries of the MacRitchie Reservoir. They were all that stood between Yamashita’s army and the all important water pumping stations at Thompson Village and Woodleigh. That evening Yamashita’s exhausted and battle weary troops were to launch one final effort to break through to the east. The leading units of the 11th Regiment of the 5th Division were by now running short of ammunition and artillery shells and the bombardment and attack was to be their final assault. It was to be a ‘make or break’ attack on the hills of Bukit Brown.

At dusk the 3rd Battalion, 11thRegiment led by Colonel Ichikawa surged up the Sime Road and charged across the Lornie Road. Colonel Shimada’s tank company parked up on the fairways of the golf course provided covering fire and his men witnessed the arms and legs of the defending Suffolks fly up into the air with every explosion. He watched as the screaming infantry disappeared into the murk and smoke along the tree line on Hill 130 then to his relief saw the torch lights and flares signal the successful capture of the temple complex. The attack had been a total success; those Suffolks that had not fled or been blown to bits by the barrage had been bayoneted in their trenches. The way was open to Thomson Village; surely Singapore would now surrender.”

The tour continued back to the main road where the group cut through a jogging path in the nature reserve for the most visible evidence of war.

And you have to watch where you are going in case you fall into this hole which will fit a man “comfortably ” (photo Bianca Polak)

This young chap seems to be charging ahead with gusto for the next leg of the tour (photo Claire Leow)

Here, Jon gets a break while BB volunteer guide Claire Leow explains some of the features of a Chinese tomb. This one is the largest single occupant tomb belonging to Onn Choon Neo. The soldiers would probably have found this useful (photo Bianca Polak)

But Jon explains how scary this terrain must have been to the Suffolk boys. Yes they could hide, but bullets could ricochet of the stones and they were be hit, If they decided to make a run for it, they face the swords of the Japanese. It was a grim prospect (photo Catherine Lim)

This was our own Ms G.I. Jane who lasted the whole tour but there was one last stop! (photo Claire Leow)

Our final “resting” place. There used to be a temple here which Colonel Ichikawa had spotted from way across the golf course which was the target of his capture. (photo Claire Leow)

If you want to know what Jon’s parting words to us was, look out for the next Battlefield at Cemetery Hill Tour , hopefully at the end of August. It’s not a difficult terrain to traverse and as I said the main route is pass the golf course but it is hot and humid. Jon is a passionate war archaeologist who with his team has uncovered intimate details about the men who fought in this battle on both sides of the divide . He draws you into the theatre of war with much verve, is great with kids and I was captivated (no pun intended!)

About Jon Cooper : He is an expat, a graduate from the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology at Glasgow University. He has spent the last three years working as the project manager alongside his partners in the Singapore Heritage Society and the National University of Singapore, for The Adam Park Project; a study into the archaeological record of the battle for the estate and the subsequent POW camp that was established there in 1942. The project’s findings r went on show at the National Library in an exhibition entitled ‘Four Days in February earlier this year. The exhibition is now over. and Jon reports, some of the exhibits has had to be stored in his home, where his sons have tremendous fun with their own battle ground”

Today, at precisely 12 pm, the sirens will sound all over Singapore to mark the darkest period in our nation’s history. 71 years ago on 15th February, the British surrendered to the Japanese after the devastating defeat of Singapore’s last strategic post of Bukit Chandu (Opium Hill.) Read Jerome Lim’s moving tribute to those who died valiantly to protect Singapore in that battle here.

a.t bukitbrown remembers the war by sharing the life and times of Tay Koh Yat, one of the war heroes buried in Bukit Brown.

Tay Koh Yat (1880 – 1957)

He was a pioneer in Singapore’s public transportation, but also a feisty patriot who started and led his own self defence force of 20,000 during the onset of the Japanese Occupation of Singapore in World War 2.

His grave located near the Bukit Brown cemetery gates is a fairly well maintained tomb and comes with benches, as if to offer a chance for people to gather and talk about his legendary deeds. The funeral cortege for Tay was grand with a reported 100 cars in attendance.

Tay was born in 1880 in Kinmen and came to Singapore when he was 22 years old. He started as a general worker in a trading company and was paid $2 a month. $1.50 was sent home to his family. Tay managed to survive on what was left because at that time, the meals, transport, housing was provided by his employer. So 50 cents was a luxury to be spend on aerated water or some porridge at hawker stalls. 2 bowls of porridge would cost only 1 copper coin, and 1 cent was equivalent to 4 copper coins.

After working for more than 10years, Tay saved up enough to start his own small firm, dealing with salted fish. He was just 26 years old. His reputation for being hard working and trustworthy led to the expansion of his business in Indonesia

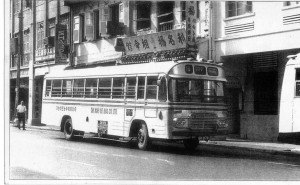

In 1938, Tay noticed that local transportation was inadequate and started the Tay Koh Yat Bus Company. He built up his fleet to 120 buses and became the largest bus operator among the 10 other bus companies.

But more than buses, Tay was admired for his patriotism and daring do in leading a 20,000 strong self defence force which he formed just before the Japanese invasion. His rallying cry “20,000 people, one heart.” The force helped to maintain order and prevent panic and chaos as people started to flee the country with the invasion of the Japanese forces.

Tay stood his ground until the eleventh hour and escaped to Indonesia to escape certain death only on the eve of the fall of Singapore. He was on the Japanese most wanted list. But before he left he had organised a 2000 strong rescue team, for people who injured by the Japanese air raids.

After the war, Tay returned and immediately started to compile the fatalities from his volunteer force and lobbied the colonial government for the same compensation given to widows and children of servicemen who died during the war. Initially rejected, he appealed and the government finally gave in.

Tay next went on to form the Singapore Chinese Appeal Committee for the Japanese Massacre victims to seek justice and compensation. It was estimated that some 50,000 people had died under Japanese hands.

In March 10, 1947, the War tribunal committee found Lieutenant General Kawamura Saburo, Singapore garrison commander and Lieutenant Colonel Oishi Masayuki Kempeitai commander guilty of war crimes and sentenced them to hang.

They had been in charge of the Sook Qing operation in Singapore which massacred thousands of ethnic Chinese.

Tay was invited to witness the execution of the two war criminals. Tay was one of only six people to witness the execution, such was his standing in the community. And, on seeing the two generals, he burst out in anger and sorrow:

“You have committed big sins and really deserve to die, but even when your soul descends to hell to suffer further punishment, still it is not enough to atone for your sins.”

Tay Koh Yat never lost his fiery nature. During the riots of the early 50s of union unrest and political instability, Tay who was by then also managing a newspaper became an indirect target. One day he received a phone call that 4 young people were burning his buses near Rex Cinema. He got his driver to take him to the scene of the arson. When he saw 2 young men burning his bus, he caught hold of one of them and exclaimed “How dare you, burn my bus!” But at 70 he was no match against a young rioter and barely escaped.

Tay Koh Yat’s tomb is in the line of the proposed new highway that cuts through Bukit Brown and his grave is slated to be exhumed, finally uprooting a pioneer and a hero who had always stood his ground.

His tomb is marked as A1 at Blk 5 division 1

A postscript on Bukit Brown ‘s war years: Many of the those who died during the 3 1/2 years of the Japanese Occupation had to be buried hastily in mass plots without tombs at the Paupers Section. They remain largely unknown.

A Singaporean recalls praying at the site of a similar mass grave where one of his relatives was buried during the war. The circumstances then dictated that bodies were collected and buried in a communal trench. This is in Block 5.

***

Here’s another blog on another war hero buried at Bukit Brown: Wong Chin Yoke. (credit: the Rojak Librarian)

Here’s a newspaper article on Wong Chin Yoke.

***

Other family details:

Marriage certificate of Tay Koh Yat’s daughter with Tan Ean Kiam as marriage solemnizer and 5 colored flag, the national flag at that time (on display at the Sun Yat Sen Memorial Hall)

Recent Comments