A Question of Public Value : Bukit Brown

by Z’ming Cik

(14 October 2013)

It has been a sweet triumph of sorts for the heritage enthusiasts of Bukit Brown who dub themselves the ‘Brownies’. They have now managed to earn international recognition for the site by placing it on the 2014 World Monuments Watch – even if that does not seem likely to change the government’s immediate plans to build a highway cutting through it.

It is not just an affirmation of its significance that Bukit Brown has been selected, alongside Venice in Italy, Yangon historic city centre in Myanmar and sites in war-torn Syria such as a 17th-century souk in Aleppo, as one of 67 cultural heritage sites currently “at risk from the forces of nature and the impact of social, political and economic change” – in the words of the New York-based World Monuments Fund.

It is also an affirmation of a universalistic ethos that any cultural heritage of the world can transcend the narrow confines of ethnic identities, and be protected by all mankind, against irreplaceable loss due to unchecked urban development or other factors. Such is indeed also the true spirit behind the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention, best known for the mechanism of the world heritage list, on which Singapore is attempting to inscribe its Botanic Gardens.

The purpose of this little article here is not to make a case for the nomination of Bukit Brown as a world heritage site – though that can definitely make a fruitful exercise, given its historical and aesthetic values based on all the knowledge accumulated. Instead, I would like to approach the issue of Bukit Brown from a more general perspective, of what is stake in general with plans to sacrifice such a site for traffic and future residential use, and how decisions should be arrived at from the perspective of public administration. For as the Brownies have expressed at a press conference last week, there is an urgent need to ‘reframe’ public discussion, away from a false dichotomy that treats it as a choice between space for the dead and space for the living.

Indeed, the issue of Bukit Brown is not a dilemma between past and future, tradition and modernity, heritage and progress, or community and nation. It may be framed instead as a question of ‘public value’ for the average Singapore citizen, whereby one should weigh between the gains of constructing a highway to ease traffic (and allowing more cars on the road) and the environmental costs which may impact on the quality of life for all residents, not to mention the opportunity costs in compromising a heritage site with value in education and tourism use.

I am borrowing the term ‘public value’ here from Mark H. Moore, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, author of the book Creating Public Value. Under such a framework of public administration, one may discuss whether a public enterprise reflects the desires or aspirations of the citizens, and also analyse whether it is cost-effective for collective interests.

This gives us a clearer picture of the problem when we consider the following points. First, in terms of desires or aspirations, 54% of Singaporeans according to the recent Our Singapore Conversation Survey have expressed a preference for preservation of heritage spaces over infrastructure, and 62% have expressed a preference for preservation of green spaces over infrastructure. The Singapore Heritage Society also cites an earlier Heritage Awareness Survey whereby 90% of Singaporeans agree that preservation of heritage would become more important as Singapore becomes a global city.

Second, plans for the 8-lane highway through Bukit Brown were announced without full disclosure of its Environmental Impact Assessment, which should rightly be of public interest. Nature Society has cited the importance of Bukit Brown as a green lung with cooling effects on the climate and mitigating effects against flash floods. We have surely seen how Urban Heat Island (UHI) effects, due to increased urban surfaces and industrial and car emissions, lead to more flash floods. The National Environment Agency is now advising Singaporeans to brace for warmer and wetter days in the next century. Should Singaporeans be inspired then to make extra more babies? Would more population growth and urban development be sustainable in the long run?

The idea of ‘sustainability’ is incidentally concerned not only with economic development but also with environment and social equity; it begs us to rationalise the needs of the present generation, in order not to compromise the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. So who are we to decide for the future generations that they have no need for natural green spaces, for authentic cultural and natural heritage?

Third, an 8-lane highway may be cost-effective for the operations of LTA and its contractors, but is it ‘cost-effective’ for all Singaporeans? On the concern of infrastructure alone, will the benefits be well distributed among Singaporeans? I believe a lot of Singaporeans would prefer to see improvements in public transport – whereby they should be managed as public enterprises rather than as profit-making private enterprises, while controlling the growth or inflow of population meantime. COEs this month have just reached 90K, and ERP rates have been rising too, so how does a new highway represent the interest of the average Singaporean? Should the dictum of the government be what former head of Civil Service, Ngiam Tong Dow recalls: “What’s wrong with collecting more money?”?

An 8-lane highway may make good business sense if the objective is to attract higher demands for car traffic. But it is a road of no return where environmental costs and the loss in heritage are concerned.

Perhaps the word ‘heritage’ is not always useful here, for some people may mistake it as being synonymous with ‘tradition’, and they assume that to acknowledge a cemetery dating back to the Qing dynasty as heritage would mean having to wear a pigtail, or to bow before the image of some dead old merchants and ask for 4D numbers. They imagine ‘heritage’ as a form of liability, instead of as a form of resource for an authentic experience of national history, or of works of art.

How the historical significance of Bukit Brown as ‘heritage’ should be interpreted, is certainly open to debates. But being ‘modern’ does not mean discarding everything of the past. We are not living in an era of Cultural Revolution somewhere in China. The National Heritage Board has also recognised the importance of Bukit Brown Cemetery and the need to work with the community for its preservation.

Being ‘modern’ also means being able to rationalise how one should help steer the development of one’s country or the world at large. Hopefully more Singaporeans will be able to look at the issue of Bukit Brown not as a matter of whether one has personal affinity to it, but from a perspective of public value.

We may ask ourselves: What heritage values does it hold on a local level and on a global level, and how would that represent the desires and aspirations of Singaporeans? In what circumstances would redevelopment be justifiable, and in what way would that represent social equity and long-term interests among Singaporeans?

We as Singaporeans need to rethink what this land of Singapore means to us, and what the word ‘progress’ truly means.

Z’ming Cik is pursuing his Phd in heritage studies in Germany.

The first tour after the announcement of Bukit Brown’s World Monuments Listing. Basil the macaw weighs in on what it means (photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

A day after the meet the media session with Brownies on the World Monuments Watch listing, the barricades are up at the roundabout (photo Milli Phuah)

SINGAPORE HERITAGE SOCIETY’S STATEMENT ON LISTING OF BUKIT BROWN ON 2014 WORLD MONUMENTS WATCH

10 October 2013

The Singapore Heritage Society is heartened that Bukit Brown has been included in the World Monuments Watch list for 2014.

Founded in 1965, the World Monuments Fund, which runs World Monuments Watch, is based in New York and is the world’s leading independent organization dedicated to saving mankind’s treasured places. Its expertise and resources, including support from UNESCO, have helped restore some 600 sites in more than 90 countries.

On this year’s Watch List is also Pokfolum Village in Hong Kong, while other sites listed in previous years include the Buddhist Remains of Bamiyan (destroyed by Taliban in 2001), the historic Gingerbread Neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti (damaged by earthquake), the Cultural Heritage Sites of Syria (destroyed or damaged in the civil war) and Penang’s Georgetown Historic Enclave (2000 and 2002 Watch List) which is now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

This is the first time a Singapore site has been included in the World Monuments Watch. Together with the Singapore Botanic Gardens’ UNESCO nomination, Bukit Brown’s inclusion represents widespread international recognition of the historical importance of local heritage sites. Indeed, Bukit Brown’s narrative of early immigrants and regional histories complements the Botanic Garden’s narrative of colonial empire to provide a more complex and complete story of Singapore.

The nomination of Bukit Brown for World Monuments Watch inclusion was advanced by the community group, All Things Bukit Brown. This has been a grassroots initiative in response to Prime Minister Lee’s National Day Rally call to Singaporeans to step forth to make Singapore a better home for ourselves.

It is also in keeping with independent surveys on heritage awareness in Singapore. The 2006 Heritage Awareness Survey revealed that almost all Singaporeans surveyed (98.4%) felt that heritage plays a positive role in their lives and that an overwhelming 90% agreed that preserving our heritage would become more important as Singapore moves towards becoming a global city.[1] The survey also revealed that 87% of Singaporeans agreed that a better understanding of Singapore’s history and heritage would increase their own sense of belonging to Singapore. Meanwhile the 2013 Our Singapore Conversation survey showed that Singaporeans wanted heritage spaces to be preserved as far as possible.[2]

This World Monuments Watch inclusion is not a one-off event but part of an on-going series of Bukit Brown-related events such as symposiums, exhibitions and public talks that have been organised by citizens and community groups that have been taking place since November 2011.

Finally, the inclusion in the World Monuments Watch 2014 list is in keeping with the Singapore Heritage Society’s call for Bukit Brown to be gazetted as a heritage site. This inclusion should be seized as the opportunity to raise greater awareness of Bukit Brown and to conduct comprehensive documentation of the greater Bukit Brown space that includes the Seh Ong, Kopi Sua and Lau Sua cemeteries, which will provide the basis for future preservation plans.

[1] Channel News Asia (18 July 2007) Heritage awareness rising among Singaporeans: study; see also http://www.heritagefest.org.sg/2007/official/images/stories/Downloads/press_release_shf2007_opening_ceremony.pdf (accessed 8 Oct 2013)

[2] https://www.oursgconversation.sg/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/OSC-Survey.pdf (accessed 8 Oct 2013)

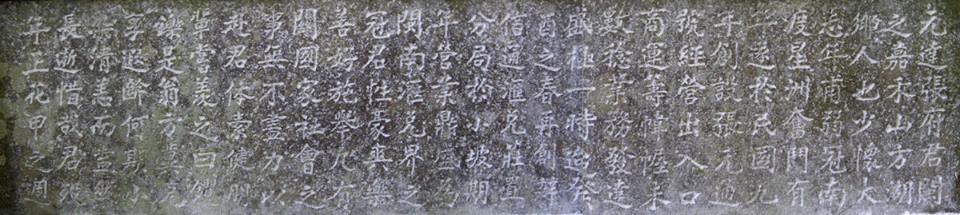

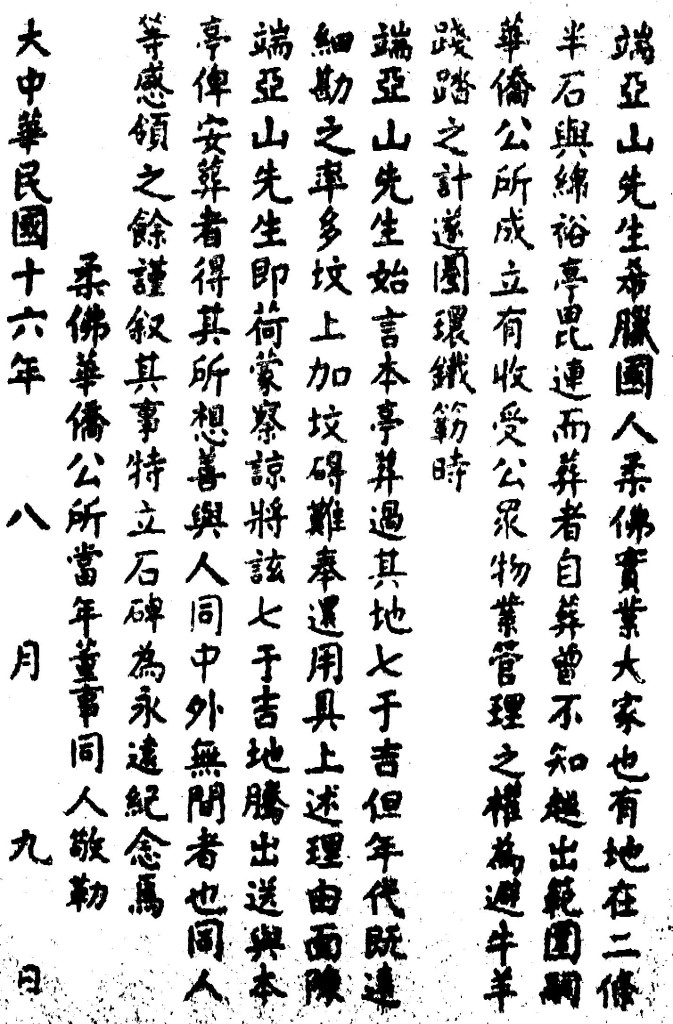

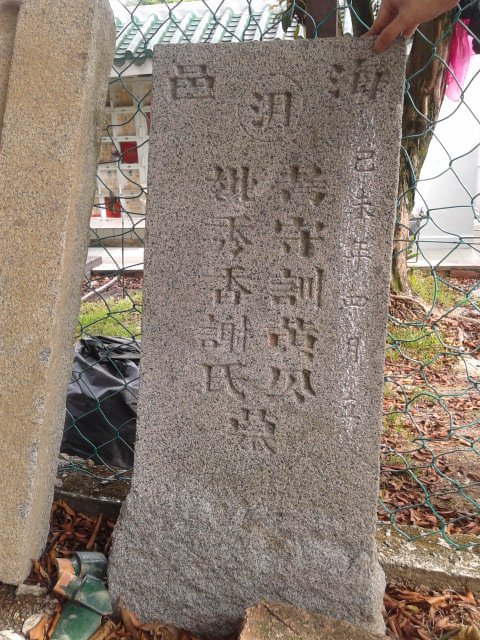

Located by the roundabout in Hill 1 (near the LTA signboard) is the tomb of Thio (Teo) Guan Tat who came from Fujian Province and was a pioneer in the remittance business.

On the altar of his tomb, is an epitaph inscribed in elegant calligraphy

Summarised by Brownie Khoo Ee Hoon:

“Mr Thio Guan Tat came to Singapore as a youth with high aspirations and who strived for many years before succeeding. Finally in 1920 he started “Thio Guan Tong” a import and export business. He profited from his business and shortly after started a remittance agency at South Bridge Road. His remittance business became the most well known and popular Hokkien Remittance company.

Mr Thio is a generous and kind man, who lend a hand to his fellow clan men and society.”

Thio’s tomb stake number 1044 will have to be exhumed to make way for the highway

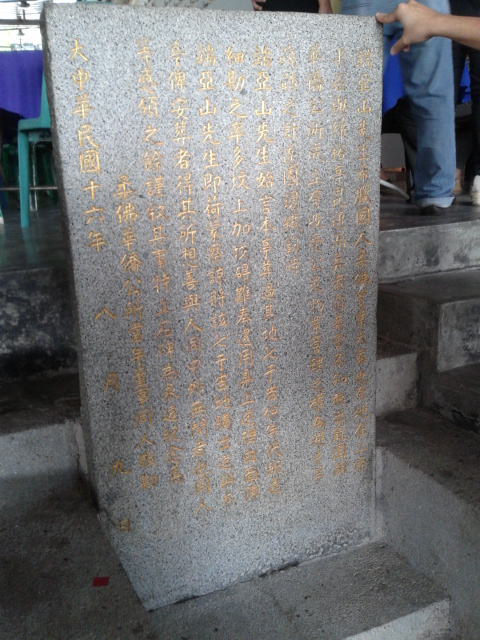

NEWS FLASH: THE CHEE FAMILY HAS STEPPED FORWARD TO CLAIM MRS CHEE KIM GUAN FOLLOWING TODAY’S NEWS PAPER REPORT IN ZAOBAO , 1 OCTOBER 2013

What began as a news flash on the Facebook Group Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown Cemetery by Raymond Goh has materialised into a newspaper article calling on descendants of Mrs Chee Kim Guan, mother of Chee Yam Chuan, to lay claim to the tomb, stake number 1818.

(This is a relocated tomb, located at Hill 2, Block 3 and is one among a cluster of 1830s tombs)

On August 25th, 2013 Raymond posted:

” Newsflash – I believe I have found the mother of Chee Yam Chuan among an old cluster of tombs staked to be removed due to an impending road project. One of Chee Yam Chuan’s grandson is Chee Swee Cheng. Today I dug the soil at the bottommost of the tombstone to reveal the only grandson on the tombstone. It was Keat Bong. Next I check out David Chng record of Chee Yam Chuan tomb inscription found in Malacca. His eldest son was also Keat Bong. Based on the son and grandson inscribed in this tombstone, I can almost confirmed that this is the tombstone of the mother of Chee Yam Chuan, Mrs Chee Kim Guan nee Khoo. This tomb is dated to 1836, and the Chees’ are one of the pioneering family to come to Singapore during its modern founding in 1819″

For more on Raymond’s research on the Chee Family, please click here

Today, 1 October 2013, Zaobao published an article on the identity of who is buried in the staked tomb, which is in the way of the 8 lane highway and still unclaimed. The following is a summary of the article by PatSg one of the members of the facebook group

* 百年古墓即将起坟 峇峇富商生母之墓无人认领?

武吉布朗3746个受新道路工程影响的坟墓,10月起将逐一起坟。在2525个至今还没有后人认领的坟墓中,有一个年代可追溯到“道光十六年岁次丙申”(1837年)的清代迁葬墓,相信是马六甲和新加坡峇峇富商徐炎泉生母之墓。

* Century-old Tomb of Mother to Wealthy Baba Merchant: On verge of exhumation and yet unclaimed (Lianhe Zaobao – 01 Oct 2013)

Bukit Brown’s 3,746 tombs affected by the new highway project will be exhumed starting from this October. Amongst the 2,525 unclaimed tombs is one that was re-interred in 1837 during the Qing emperor Daoguang’s 16th year of reign (also the year of the Fire Monkey). This tomb is believed to belong to the birth mother of the wealthy Malacca and Singapore Baba merchant Xú Yán Quán [徐炎泉: Chee Yam/Yean Chuan].

原籍漳州府龙溪县的徐炎泉(1819-1862)和父亲徐钦元都是海峡殖民地成功商人,曾经富甲一方,生意遍布马六甲和新加坡。徐炎泉21岁时就已经当上马六甲福建帮领袖,不过他在1862年遭枪杀,时年43岁。

Hailing from Longxi county of Zhangzhou prefecture, both Xú Yán Quán [Chee Yam/Yean Chuan] (1819-1862) and father Xú Qīn Yuán [徐钦元: Chee Kim Guan] were successful and extremely wealthy merchants of the British Straits Settlements with businesses all over Malacca and Singapore. Xú Yán Quán was already the leader of the Malaccan Hokkien community at age 21, but was gunned down in 1862 at age 43.

原来徐炎泉的这位生母,百多年来一直静静的躺在武吉布朗坟场,而且很快便要被挖走!除了徐炎泉生母,他儿子徐桂梦和媳妇周吉娘的墓也在武吉布朗。

吴安全相信徐炎泉依然有后人在新加坡和马六甲,希望他们看到报道后,能尽快与他联络,认领被遗忘多时的坟墓。

It turns out that Xú Yán Quán’s [Chee Yam/Yean Chuan’s] birth mother has been resting peacefully at Bukit Brown Cemetery for the past 100-plus years, and would very soon be exhumed ! In addition to his birth mother, the tombs of his son Xú Guì Mèng [徐桂梦: Chee Quee Bong] and daughter-in-law Zhōu Jí Niáng [周吉娘: Chew Kiat Neo] are also located at Bukit Brown.

Raymond Goh believes Xú Yán Quán [Chee Yam/Yean Chuan] have descendents still living in Singapore and Malacca, and hopes that after reading this report, they would contact him as soon as possible to claim the long-forgotten tomb.

============

Additional Genealogical Summary by PatSg

** Chee Yam/Yean Chuan (徐钦元 Xú Qīn Yuán: 24 May 1818/19/20 – 28 Jul 1862)

* Father: Chee Kim Guan (died 13 Jan 1839)

* Mother: Siok Hui (淑惠 Shū Huì: posthumous name, re-interred tomb dated to 1836)

* Wife: Tan Liat/Lian Kian

* 2 Daughters

* 10 Sons: Chee Gin Siew (alias Cheah Jin Siew), Chee Him Bong, Chee Pee Bong, Chee Teck Bong, Chee Hoon Bong, Chee Lim Bong, Chee Hee Bong, Chee Quee Bong, Chee Beck/Peck Bong, Chee Siang Bong

Editors Note: The tomb of Mrs Chee Kim Guan is part of a cluster of over 50 tombs which have been reburied in Bukit Brown. The tombstones date back to 1830s, which indicate that these would be pioneers who predate the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819. Information on this cluster of tombs was not recorded in the Bukit Brown Burial Registry. As such the only way to identify who are buried in this cluster is first, to decipher the names and inscriptions on each individual tomb and conduct further research. This was how Raymond identified the tomb of Mrs Chee Kim Guan

Bukit Brown, Development and Possibilities for Singapore

By Ian Chong

Recent events and public discussions about public transport, the environment, and heritage should give pause to the proposed construction of the dual four-lane carriageway across Bukit Brown. Singaporeans have one last opportunity to consider the consequences of irrevocably altering the face of an important part of our nation’s natural and cultural landscape before the planned exhumations begin in October 2013. Surveys for Our Singapore Conversation indicate that 62 percent of Singaporeans prefer preserving green spaces over constructing roads and other infrastructure, while 53 percent prefer heritage preservation over infrastructure building. (OSC Survey, p. 6) Staying road construction over Bukit Brown demonstrates responsiveness to public needs.

Simply building roads, such as one over Bukit Brown, does not address the fundamental reason underlying congestion in Singapore. As Kishore Mahbubani, dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, pointed out, the fundamental challenge facing road space in Singapore is sub-optimal public transport, which heightens demand for car use. (ST, Sep 14) Recent steps by the LTA to raise ERP rates and introduce new considerations for the COE underscore the fact that controlling vehicle population should be key to addressing the traffic snarling our roads. The heavy traffic on Lornie Road during rush hours comes from vehicles filtering on and off a congested PIE, an issue a road through Bukit Brown is unlikely to solve. In fact, Singapore can probably never build enough roads if current approaches to car use and public transport are not thoroughly re-thought.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s last National Day Rally should provide more impetus for maintaining Bukit Brown in its current form. According to Mr. Lee, new plans to develop Singapore’s southern and eastern coasts along with Paya Lebar mean that, “we do not have to worry about running out of space or possibilities for Singapore. We are not at the limit, the sky is the limit! We are creating possibilities for the future.” This means that there is space for Bukit Brown in its current form in our future and those of our children.

As physical changes in Singapore become ever more prevalent, the remaining tangible markers of our unique heritage and history only grow in importance to society. This is a reality that digitisation can never fully replace or replicate.

In fact, the Prime Minister’s National Day Rally statement about being able to maintain possibilities for Singapore stands in stark contrast to National Development Minister Khaw Boon Wan’s claim that it is necessary to sacrifice Bukit Brown and nature for construction. (Zaobao, Sept. 28) Today’s Singapore is no longer in the 1960s where infrastructure development was imperative.

The haste to construct the dual four-lane carriageway – and other follow-on developments – over Bukit Brown may even be counter-productive. Flooding earlier this month serves as a reminder of the need for development projects to proceed with caution. As the NEA subsequently stated, “Rapid development and urbanisation…are likely to be significant factors which may explain this trend [of heavy precipitation leading to flooding].” (Today, Sept 13) The Expert Panel on Drainage Design and Flood Prevention Measures likewise noted, “increased urbanisation in the Stamford Canal Catchment might have been a contributing factor to the 2010 and 2011 floods…” (p. 13)

Moreover, the panel observed that “other than generating higher and faster surface run-off, increased urbanization may also bring about other impacts such as increased heat production, changes in rainfall patterns and other climate change impacts…” (p. 13) Panel recommendations to mitigate the effects of urbanisation is recognition of the relationship between rapid, large-scale development and flooding. (p.1, 9, 15, 52, 55) Notably, the Environmental Impact Assessment for the road across Bukit Brown remains unavailable for public access.

Building the road over Bukit Brown may prove to be a temporary patch rather a real solution to the challenges of congestion, and can potentially create more difficulties down the line. The LTA and URA should hold off construction until there are more comprehensive ad appropriate ways to address the environmental, heritage, traffic, and development issues that intersect at Bukit Brown.

At a minimum, there ought to be a rigorous, publicly available study first. This is a first step toward finding a more comprehensive and sustainable approach to the issues above. Halting construction clearly comes with costs, but these may be much lower that those from building the road. Singapore is worth the extra effort.

Ian Chong works at a tertiary institution. His comments are in his personal capacity. An edited version of this commentary first appeared online in Today 30 September 2013

Dateline 27 September 2013

This morning descendants and members of the Poit Ip Huay Kuan marked the 130th anniversary of Teochew leader and King of Gambier, Seah Eu Chin (1805-1883). In November 2012, his grave was found by the Goh brothers, Raymond and Charles. And since then descendants have been making tracks up to Grave Hill, in Toa Payoh to pay their respects.

“Under the initiation of Teochew Poit It Huay Kuan and the endorsement of Ngee Ann Kongsi, it was a great moment in current Singapore Teochew history that many Teochew Organizations and Seah family members gathered at Seah Eu Chin’s tomb for a memorial service for his 130th death anniversary.” Zaobao 28 Sept 2013 (translated by Raymond Goh)

Today offerings were made at the grave which had been prepared for the occasion. Thank you to Brownie, Khoo Ee Hoon for documenting this commemoration of Seah Eu Chin.

2 days before the 130th Anniversary when the Brownies visited, the marquee was already up and grave cleared (photo Catherine Lim)

Zaobao reporter Yen Yen who covered the discovery of Seah Eu Chin’s tomb a year back was at the 130 Anniversary to interview descendants ( photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

Members of Poit Ip Huay Kuan who were responsible for the major preparations for the 130 Anniversary of Seah Eu Chin (photo Khoo Ee Hoon)

Both Raymond and Charles Goh were in attendance at the anniversary this morning.

Postscript: Raymond reporting from the event posted this photo on the facebook group page.

“”It is a remembrance ceremony on the occasion of 130th death anniversary of Seah Eu Chin’s death. An eulogy was read out during the memorial service.”

From Sugen Ramiah commenting on the layout of the offerings on the table : What you see above is a Teochew style remembrance. What is seen follows a hierarchy – 5 sets of rice, wine and tea served . Twelve buns/kuehs, odd numbers of poultry and seafood and odd numbers of fruits offerings.

There were 3 chairs placed in the front of the offerings (not seen in the photo above)

From Tay Hung Yong: The three chairs are meant for Seah Eu Chin and his two wives (correct me if I am wrong). The 5 sacrificial animal offerings are quite common among Southern Chinese. There should be at least 8 different dishes. Twelve buns represent 12 months in the calendar. For Teochews, fruit offerings are usually in 4 not 5. The joss paper they offered are usually meant for deities.

Editors note: In any ritual there are different interpretations on how they are conducted and how the different offerings are laid out.

A member of the facebook group Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery recently posted a series of maps and articles which pointed to coolies living in Bukit Brown in 3 blocks, near Block or Hill 3. The coolies would most likely have worked on the maintenance of the tombstones and the cemetery.

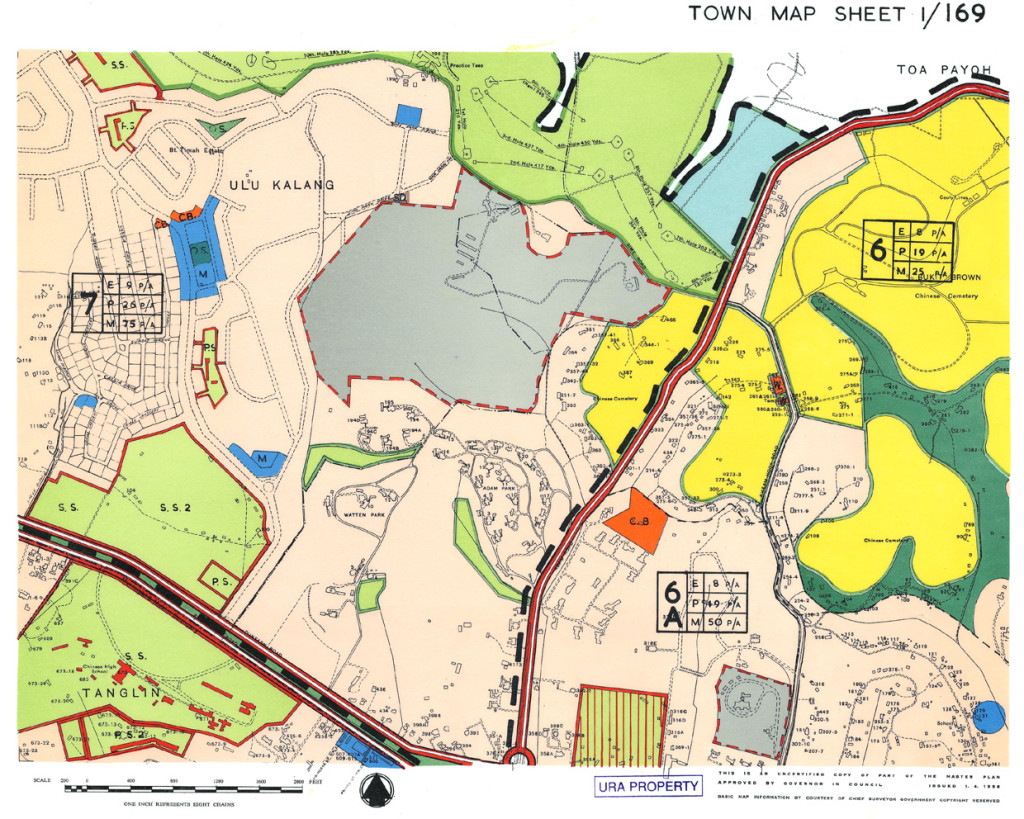

1958 map showing the “cooly lines” of 3 blocks, at the yellow section just above the number 6 on the right line (Map Source: URA)

According to the posts

“Both the 1958 town map & NAS’ BBC map show 3 blocks of “Coolie Lines” (ie. indentured labourer housing) along the tarmac road at Block 3 (at the demarcation between Div A & B ), a short distance before the “eco-bridge” that overlooks the stream.

http://www.nas.gov.sg/docs/Bukit_Brown_Map-1.jpg

http://www.ura.gov.sg/dc/mp58/dcdmp58tm169.htm

The said “coolie lines” could’ve already existed when BBC (estd. Jan 1922) was still the private burial ground of Seh Ong clan. In Oct 1928, the structures were reported to be “in a very dilapidated condition, and it is proposed to rebuild them”. In Aug 1929, Lian Hup Co. won the tender ($6,200) to erect the proposed new “Coolie Lines”.

As it was common to have resident indentured coolies living in cemeteries, might some of the paupers’ or unknown/ unmarked graves at BBC belong to these resident coolies ?For instance, when ~237 WWII-era tombs at BBC were exhumed in 1965 for the realignment of Lornie Rd, the exhumation list included 2 plots whose residential addresses were stated as “coolie lines”. For the “Unknown” plot, the burial date was 05 Jul 1942, & the address was “5 Coolie Lines SHB” (in this case, the Cantonese coolie lines of S’pore Harbour Board).”

Extract from Infopedia on Coolies : Chinese coolies formed the early backbone of Singapore’s labour force, engaged mainly in hard physical labour. They were mainly impoverished Chinese immigrants who came to Singapore in the later half of the 19th century, seeking their fortune but serving instead as indentured, unskilled labourers. Coolies were employed in almost every sector of work including construction work, plantation work, in ports and mines and as rickshaw pullers.

The Archived Newspaper Reports:

* SG Free Press (23 Oct 1928) – Proposal to rebuild dilapidated coolies lines at BBC: http://newspapers.nl.sg/Digitised/Article.aspx…

* SG Free Press (28 Aug 1929) – Lian Hup Co. awarded tender to rebuild coolie lines at BBC: http://newspapers.nl.sg/Digitised/Article.aspx…

* ST (26 Mar 1965) – PWD Exhumation Notice for BBC (Lornie Rd alignment): http://newspapers.nl.sg/Digitised/Article.aspx…

Mian-Yu-Ting Cemetery, Johor (Part II)

by Choo Ai Loon

(Ai Loon continues from part one of her blog post on Mian-Yu-Ting Cemetery )

Among the tombstones at the Mian-Yu-Ting , is one belonging to Wu You-Xun (邬有询), which pays tribute to his alma mater, Chinese High School (華僑中學 in traditional Chinese characters)

A student with a promising future, Wu You-Xun (邬有询) aspired to become a doctor, In 1920, after completing his Senior Cambridge examination (equivalent to GCE “O” levels) , he enrolled at Chinese High. He graduated among the first batch of students, two years later. In the graduation year book, he was described as a hardworking student who “had no time to chit-chat as time was too precious”.

Wu excelled in English and was a committee member of an English speech society, which I presume was the “Nanyang version of the Toastmasters Club”, and chief editor of an English magazine.

But alas! Wu passed away at just 22 years old, a year after graduation. Inscribed on his tombstone is “graduate of Chinese High School” is a reflection of how proud he must been of his school

In contrast, one grave has only 3 characters inscribed but no name. Gu-ren-mu (古人墓), literally means “the tomb of someone who has passed away”.

This typical Teochew tomb which resembles an arm chair, a pair of couplets in red on the scroll pillars.

The arms of the tomb curve gracefully and there is a dragonhead carved on it The usual practice of depicting the whole dragon it seems has been adapted to just a dragon’s head. I have observed these variations in motifs and representations. This dragon appeared benign compared to the fierce-looking ones found in older tomb carvings.

Another grave had steps leading up the tombstone perhaps imitating a stupa, influenced by Buddhism.

The Tomb of She Mian-Wang

She Mian-Wang (佘勉旺), belonged to a wealthy Teochew family. The surname “She” is more commonly spelt as Sia or Seah.

The She Mian-Wang family profile in Johor parallels that of the Seah Eu Chin in Singapore. Both families had made their fortune from the cultivation and trade of gambier.

Seah Eu Chin’s tomb was discovered in 2012 within Greater Bukit Brown, in a forested area called Grave Hill in Toa Payoh West, Singapore. He co-founded and led the Ngee Ann Kongsi in Singapore, to look after the religious needs and welfare of early Teochew migrant workers.

Similarly, She Mian-Wang was an important figure in the Ngee Heng Kongsi The enormous plot size and the expansive tomb arms of She’s grave reflects his status and wealth in those days. Interestingly, his tablet is enshrined and worshipped at Pu Zhao Chan Si Temple (普照禅寺) in Singapore.

So could these two powerful families in the Teochew community be related? I leave you with this parting thought .

My thanks once again to Mr Bak Jia How and Mr Pek Wee-Chuen for the insightful and enjoyable tour of Mian-Yu-Ting.

Thanks to Mr Bak Jia How and Mr Pek Wee-Chuen for the insightful and enjoyable tour.

Choo Ai Loon, works as a translator and is passionate about art and heritage, She supports Hair for Hope for children with cancer. She blogs at http://chooailoon.wordpress.com/2013/05/05/hair-for-hope-2013/

by Choo Ai Loon

The Mian-Yu-Ting Cemetery (绵裕亭) across the causeway in Johor, Malaysia, has an area of about 60 acres. The cemetery which has been closed for burial includes a casket company, a crematorium and two columbaria, among other facilities.

I attended a tour of the cemetery led by Mr Bak Jia How and Mr Pek Wee-Chuen who are alumni of Foon Yew High School in Johor. The tour was to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the school, and dedicated to two of the four founders who were laid to rest in Mian-Yu-Ting.

We also visited the graves of other contributors to Foon Yew and stories about them were shared. At the same time, I learned other interesting facts about the graves, in particular, the meaning behind the unique inscriptions .

The land for the cemetery was a gift by Sultan Abu Bakar in 1885. In the 1920s, due to poor management, burials had mistakenly crossed over onto an adjacent piece of land. That land was owned by a tycoon, Al-Habib Hasan bin Ahmad al-Attas of Arab origin, but born in Malaya. He however kindly agreed to donate a part of the land to the cemetery. As a token of gratitude, a Rosetta stone was erected within the compound to remember his generosity.

The Chinese character “氵月” on the tombstone circled below means ‘Qing (Dynasty) without a leader’ (清无主). This was a secret word created to symbolise the movement to overthrow the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) and to revive the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

However, engraving the character on a tombstone in Nanyang (Southern Seas or south of China) in the last 200 years did not necessarily mean one was active in the movement. It can be interpreted to symbolise the unity among members from a certain cohort or gang, formed by early Chinese migrants to Nanyang.; in this instance, the Teochew community.

Notably, most of the tombs in Mian-Yu-Ting that carry “氵月” character are on Teochew tombs and not found on the Cantonese tombstones there . Have you seen the same character at any tomb in Bukit Brown?

There is tomb adorned with Majolica tiles which was built when the Ngee Heng Kongsi was ordered to dissolve in 1919. The Ngee Heng Kongsi was a powerful Teochew gang in Johor and an offshoot of the Tian-Di-Hui (天地会) secret society in China. The society aimed to topple the Qing Dynasty so as to reinstate the Ming Dynasty.

That said, the overseas offshoot of Ngee Heng Kongsi was largely committed to taking care of the welfare of early Chinese immigrants. When it wound up, a fraction of its funds was spent on building this tomb, with the Chinese words of Ming-Mu (明墓), meaning Ming tomb, engraved on the headstone.

The remaining fund, a substantial sum at that time, was donated to Foon Yew School. And in return, the school would have to perform rituals at the tomb twice a year, on the 3rd day of the third Lunar month (spring) and the 25th day of the seventh Lunar month (autumn). For almost a century now, the school continues to fulfil its promise.

No one was buried under the tomb. Instead, a catacomb was said to have been built to place ancestral tablets of important members of the gang, and to safe keep sacred objects. Notably, Ngee Heng Kongsi had established one of the earliest Chinese settlements in Johor. We certainly won’t be where we are today without our pioneers.

Here are some highlights from other graves

At one grave, there is a larger-than-usual placement of the Guardian Deity of Earth which is comparable to the one at Ong Sam Leong’s in Bukit Brown.

In Singapore and Malaysia, the Guardian Deity of Earth may be addressed in Mandarin as Tu-Di-Zhi-Shen (土地之神), just like the one in the photo, or Hou-Tu (后土) or Fu-Shen (福神). Have you seen another name being used in Bukit Brown?

A mythical creature Ao-Yu (鳌鱼) has a dragon’s head and a fish’s body, it is believed to have transformed from a carp.

I hope these discoveries may lead you to exclaim “oh I see!”; or trigger a memory: “oh I have seen this somewhere before!”.

I would like to thank Pek Wee-Chuen and Bak Jia How, for an enjoyable tour and sharing their knowledge with me.

Look for part 2 of my journal on Mian-Yu-Ting. Highlights include, a Johorean connected to a high school in Singapore and, the story of a family business which parallels that of Teochew leader, Seah Eu Chin.

Choo Ai Loon, works as a translator and is passionate about art and heritage, She supports Hair for Hope for children with cancer.

She blogs at http://chooailoon.wordpress.com/2013/05/05/hair-for-hope-2013/

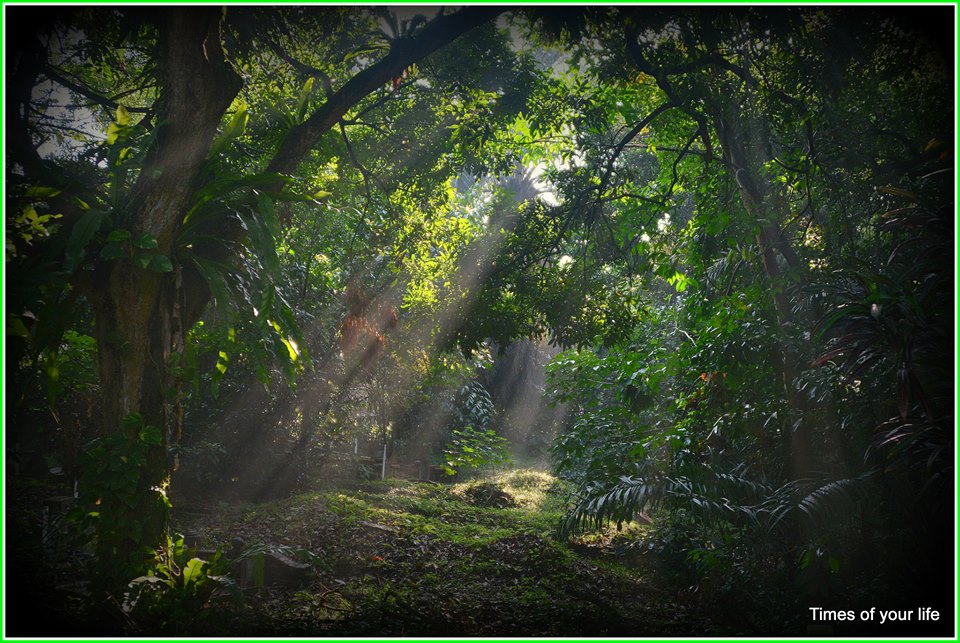

“It started off as a dream. A dream to create a video where one or more musicians play beautiful music as they explore the ‘invisible’ gem of Bukit Brown “

Environmentalist Cuifen wanted to make Bukit Brown more “visible” to share its beauty and tranquility.

The result ” Ukelady meets Ukebaba in Bukit Brown Conversations”

Please share, and share and share this video and let it go viral, so others can enjoy Bukit Brown too!

More on Cuifen’s thoughts on Bukit Brown in her blog Conscious Steps

Cuifen would like to thank :

Ukelady – Yen Lin

Ukebaba – Su Min

Video editor – Jasmine

Video & mic equipment – Ee Hoon

Recent Comments