Every year on the 1st day of the 7th month lunar calender, the Chinese believe the gates of hell are opened, and the spirits are released to the earthly realm. Liew Kai Khiun shares his reflections of the rituals conducted at Bukit Brown Cemetery for the wandering souls.

Remembering the Forgotten and Forsaken

I had the opportunity to participate in one of the rituals for the lunar 7th Month festival at Bukit Brown Cemetery. Known as the “Hungry Ghost Festival”, this is a time where souls are released from hell for a month to roam the human realm. Although considered an inauspicious month where no weddings and property transactions takes place, it is actually a time for the living to remember the forgotten dead. Even the practice can be seen to be feudal, it is actually a spiritual extension of acts of charity to the wandering and homeless souls.

Long before it was known to the larger public, devotees from temples have quietly organized rituals to commemorate the nameless souls from the pauper graves of Bukit Brown Cemetery. While I have participated in Chinese folk religious rituals since I was a kid (particularly during military service), being self-taught in Karl Marx, I am not a very religious person. But, since the finalization of plans to run a mega expressway through Bukit Brown Cemetery by the end of the year, I felt the need to apologize and beg for forgiveness for not doing enough to stop this soulless project of the living from penetrating into this soulful place of the dead.

The night with this particularly group of devotees and the priest has been my most soulful and spiritual experience in Bukit Brown Cemetery. As the priest blessed my car before I exit the premise in the wee hours of the morning, I have never felt so tranquil and at ease driving home. Although these activities are done away from the public limelight, I feel the need to pen my thoughts here to clear common misconceptions and prejudices of such practices.

I am also truly humbled by their continued efforts without any intention of public recognition whatsoever. For those who have been forgotten and forsaken in life, it is rituals and activities like such that we try to remember them in their after-life.

It is not the road, but the rich cultural and ecological diversity that gives Singapore a soul.

Co-existence of Culture and Nature: This is a wonderful moment where smoke from the incense emerges amidst the hanging roots and leaves

Footnote: Unlike in HDB estates, these devotees do clean up and pack up after the rituals end

For more from Kai Khiun’s album, please click here

Since the news of the redevelopment of Bidadari Cemetery in the late 1990s, Kai Khiun has been involved in advocacy of Singapore’s built and natural heritage. As an academic, he has also been involved in the research and documentation of socio-cultural and historical issues in East and Southeast Asia, and has published some works recently on the use of the social media by conservationists in Singapore.

We need to leave something for our future generation. A piece of history that can be seen and felt, and not read from text books in schools and libraries.

acknowledgement to Goh Hiap Leng from NTUC Media , 《生活》月刊2013年7月号 (“Sheng Huo” Jul 2013).

(Source: 文章来自《生活》月刊一三年七月号) (“Sheng Huo” Jul 2013)

Abstract of feature, translated by Raymond Goh:

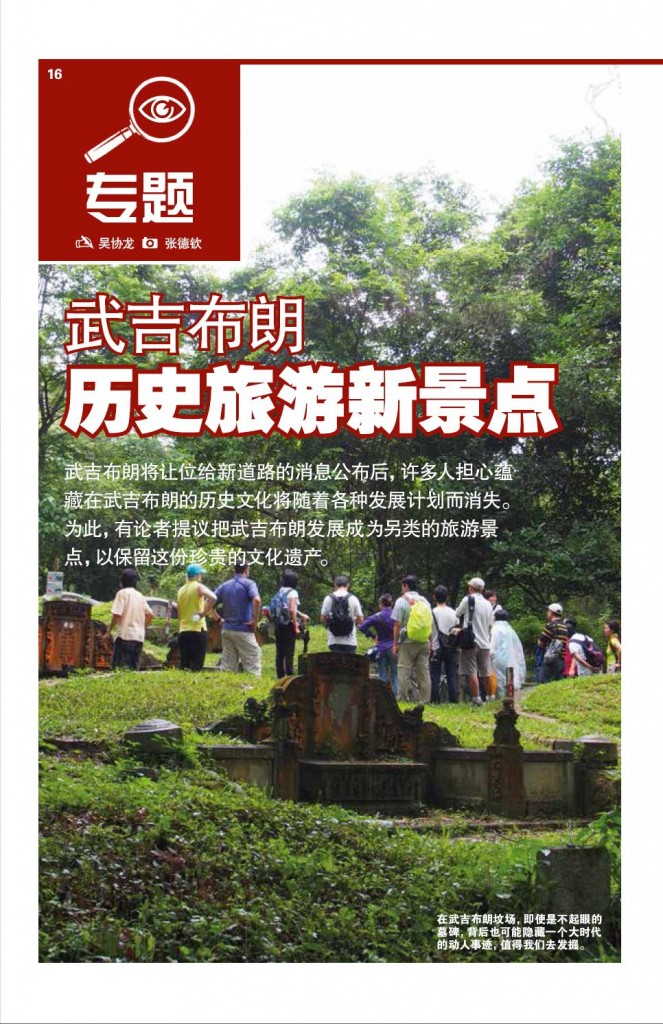

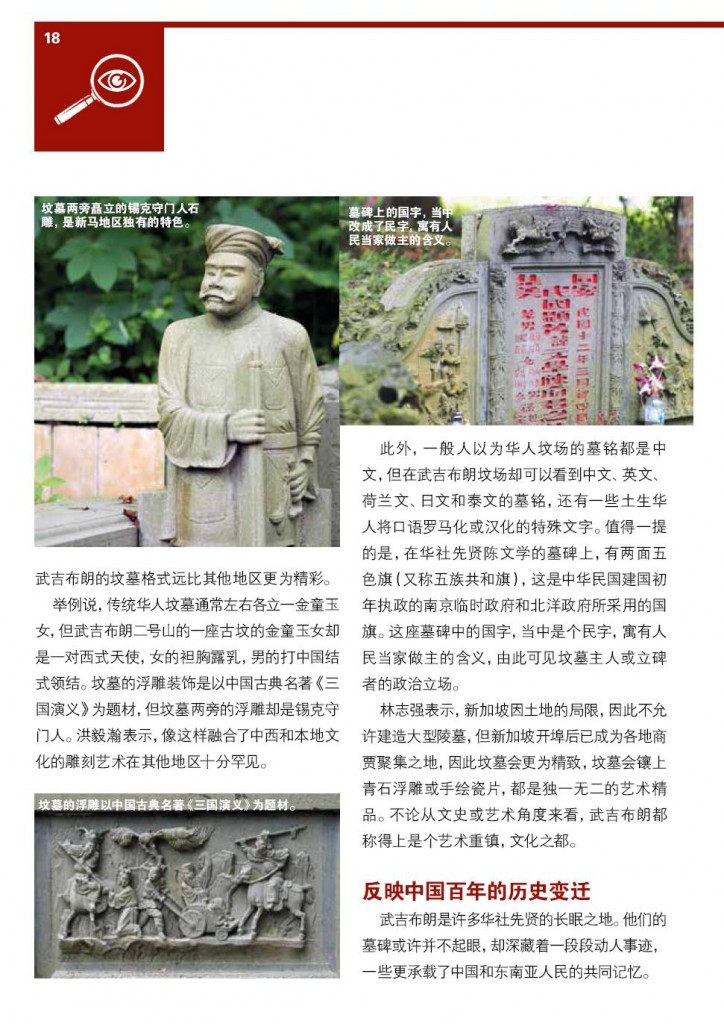

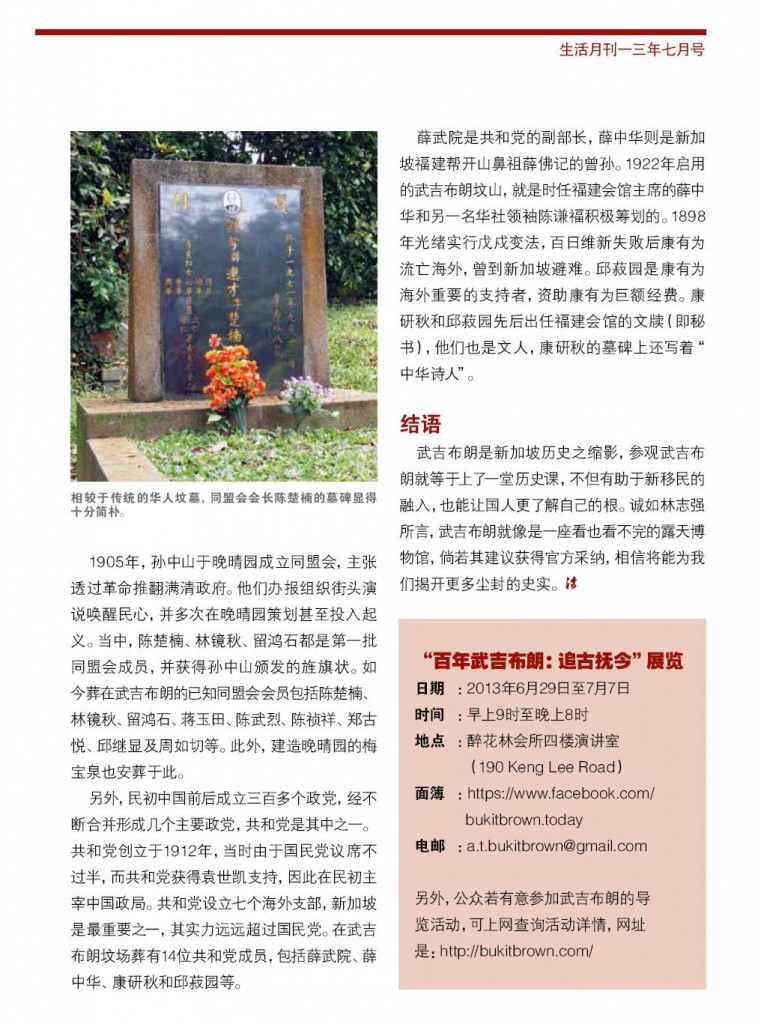

“Ever since the news that Bukit Brown is to give way to a new highway, many people are concerned that the cultural heritage in Bukit Brown would disappear in line with further developments. Thus, there are people who suggest that Bukit Brown should be developed into an alternative tourist attraction, in order to preserve this precious heritage.

Volunteer guide Walter Lim felt that Bukit Brown reflect the history of Singapore being at the cross roads of the East and West, the centre of Nanyang, and the mother of the Chinese revolution, and can be a very worthy historical attraction which encompass all these cultural artifacts.

Another guide Yik Han mentioned that the history of Singapore does not start after independence, but before that, Singapore was already a prosperous place. Bukit Brown provides an invaluable resource for the study of pre-independence Singapore, and how our early pioneers helped to build the current foundation.

Bukit Brown is a snapshot of Singapore history, visiting Bukit Brown is like undergoing a lesson in history. Not only does it help in the immersion of new immigrants, but it also helped its citizens understand more about their roots. It is like a vast living museum and one can never see enough, and will keep on surprising and enlightening us with new facts if this proposal is accepted by the authorities.

Through time and distance, Grace Seah remembers and pays tribute to her grandparents buried in Bukit Brown.

“To forget one’s ancestors is to be a brook without a source, a tree without root”

(Chinese proverb)

As a young girl, I remember accompanying my parents to Bukit Brown Cemetery to pay respects to my late grandparents every Qing Ming. It was always an exciting time for me, folding the paper money into boat shapes, helping to trim the overgrown vegetation around the tombs, sweeping the surrounds and running around admiring the neighbouring tombs.

As the years went by, I gradually stopped attending to this annual ritual and left it entirely to my parents to do their filial duty on their own. My life took on a momentum of its own that left me with hardly any time to think about my ancestry and heritage and old traditions of my childhood. In time, I moved to another country to set up home there with my own family.

With the sense of loss I felt during the first few years of settling into my adopted country, there was renewed impetus to capture and treasure the precious memories of my Peranakan heritage and family mementos. The one memory I had of my grandparents was this beautiful old photo taken around the year 1934. It shows my paternal grandparents with my father, their youngest son and his 2 elder brothers.

I never grew up knowing my Mama and Kong Kong as they passed from this world before I could remember much. However, I have always felt particularly drawn to them through this photo. It was as if they were always smiling at me. I grew to love this special family photo with all my heart.

In this family photo are:

The matriarch and patriarch are my paternal grandparents. Both were buried in Bukit Brown. My father is the youngest boy in the picture. The dapper young gentleman in the black suit is his 2nd brother Tan Kim Teck and my 3rd uncle Tan Kim Cheng is in the middle. In those days daughters were not part of the family photos. One of my dad’s sisters Tan Imm Neo eventually married Cheang Theam Chu, son of Cheang Jim Chuan and grandson of Cheang Hong Lim.

My grandparents came from humble backgrounds but worked hard to raise a large family in the Peranakan tradition of those times. My grandfather passed away in 1946 and my grandmother single-handedly presided as the matriarch in the family until her death in 1964.

Through a series of coincidences and unexpected events, I was one day led to the amazing work being done by the Bukit Brown community to preserve the heritage that is Bukit Brown. Suddenly memories of all that I loved about Bukit Brown and memories of visits to my grandparents graves came rushing back at such a speed that it left me breathless. For reasons that only God and the Universe understand, I was given this one last chance to help locate the tombs of my grandparents before the government deadline of 31 Dec 2012.

It was a family photo that started the chain of events identifying my grandparents’ tombs. It was an unbelievable feeling when I finally reconnected with them. My 88-year-old father was also pleasantly surprised with the discovery, as with age, he had himself lost touch with his parents’ graves at BB.

I would like to think that Mama & Kong Kong had a hand in making all this happen. Who would have thought that this beautiful family photograph would be the key to ensuring that their earthly remains will finally be laid to rest permanently amongst the others, in a special place, never to be forgotten again.

Editors note : The tombs of Tan Keng Kiat and Chan Gin Neo are staked and will have to be exhumed to make way for the eight-lane highway. When Grace Seah posted a request on the Facebook page to help find their tombs, the response was near instantaneous, as Brownie Ee Hoon had remembered taking photos of the tombs and noting its unique features.

By Eugene Tay

Eugene helms the movement “We support the Green Corridor” and is one of the partners of All Things Bukit Brown.

The Green Corridor is a former railway while Bukit Brown is a cemetery, so different yet so similar. The Green Corridor and Bukit Brown both connects the past and future, and both involves heritage and the environment. I hope that all of you can support the preservation of Bukit Brown, just as you have actively supported The Green Corridor so far.

I supported The Green Corridor proposal by NSS because I feel that it would improve Singapore’s long-term resilience. The biggest threat to Singapore is apathy, and when Singaporeans do not feel a sense of belonging and are not bothered with what goes on here, then Singapore is in trouble.

For Singapore to survive and prosper in the long term, it is necessary to have more opportunities in preserving our shared memories and creating our shared vision. And keeping the railway lands as a Green Corridor is one opportunity not to be wasted.

Similarly, I feel that Bukit Brown is another excellent opportunity that enables Singaporeans to feel they belong here by remembering our past and creating our future.

Remembering Our Past

Bukit Brown tells the stories of our forefathers who built Singapore, and creates opportunities for history education and discovery. The cemetery connects Singapore’s past and present, and allows us to understand that Singapore’s success is built up by our forefathers’ sweat and tears, and should not be taken for granted.

We should preserve Bukit Brown because it helps us remember our past and keeps us rooted to Singapore.

Intense interest in the historical tombs and shared camaraderie on public tours (photo Catherine Lim)

Creating Our Future

Bukit Brown presents the opportunity for transforming the cemetery into a world-class living outdoor museum or heritage park. If this transformation adopts a bottom-up approach and with stakeholder engagement, it would allow us to come together, plan and work towards a future Singapore where heritage, nature and our economic needs can co-exist.

We should preserve Bukit Brown because it enables us to work together and build bonds and resilience, and to create a space where our children and their children can enjoy and be proud of.

Support Bukit Brown

Singapore is a young nation and needs more common spaces like The Green Corridor and Bukit Brown to remind us how we got here and why this is home, and to create opportunities for building our future social resilience. Support Bukit Brown, just as you have supported The Green Corridor.

Here’s what you can do:

1. Sign the petition to save Bukit Brown 100% at the SOS Bukit Brown – Save Our Singapore website.

2. Join the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook Group to understand more about Bukit Brown and keep yourself updated.

3. Spread the message by sharing with your friends about Bukit Brown and urging them to sign the petition.

In the end, our society will be defined not only by what we create, but by what we refuse to destroy. – John C. Sawhill

By Eugene Tay

“Bukit Brown : What We Have Really Lost” by Joshua Chiang

(This essay first appeared on The Online Citizen on March 20, 2012 and is reproduced here with the permission of the writer)

On a separate note, I found out from one of the SOS Bukit Brown volunteers that Tan Tock Seng’s grave on a knoll at Havelock Road would also have made way for a road because – get this – the people who planned the road had no idea that the grave belonged to him. It was only through the intervention of activists that the tomb was saved. This is what happens when we’ve lost our roots. We even believe our ancestors are as equally pragmatic as us.

All Things Bukit Brown notes: Till today, there has been no engagement from the relevant bodies on Bukit Brown and development plans are proceeding, deaf to the community of diverse voices which has grown. More have been coming for public tours conducted by volunteers; it has become the subject of lessons, videos, books, heritage forums on and offline and incorporated into a play. Soon it will be the inspiration of the art of a New York artist. He is calling his next exhibition “Extinction”

Dateline : 26 Tuesday 7-pm – 9.30pm

The Ngee Ann Kongsi auditorium of the sprawled out spanking new campus of University Town, NUS fills up. The event: “Moving House” jointly organised by NUS Museum and All Things Bukit Brown. The highlight: a timely resurrection of an award winning documentary by film maker Tan Pin Pin. “Moving House” made in 2001 which followed the Chew family , one of 55,000 Singapore families forced to relocate the remains of their relatives to a columbarium as grave sites made way for urban redevelopment. The screening was followed by a presentation by Dr Hui Yew Foong on the first exhumation documented at Bukit Brown on 3 June 2012 by his team which also included a video clip of present day descendants at the grave of their ancestors. It was a reprisal of a poignant scene from Pin Pin’s Moving House 11 years ago to the present which struck a chord with Judith Huang who was in the audience, and moved her to write in her blog about matters of national importance the morning after. We reproduce it here with her kind permission

Matters of National Importance

For most the glittering success of Singapore is like a mirage, can see but cannot touch. – a friend

I consider myself a patriotic Singaporean, and have been since I was a small child. Perhaps it is a quirk of my character, a function of being unusually enthusiastic about group identities, or perhaps I am just one of those people more susceptible to propaganda. I can’t be sure. But every morning, from the age of 7 through 18, when I recited the Singapore pledge, I meant every word of it (and still do). I still remember this feeling of national pride in progress – particularly economic and technological, that was thick in the air in the 80s and 90s. In particular, when I was in primary school, the object of national pride was the MRT (built in 1986) and Changi airport, both of which featured prominently in any national day poster we would draw for primary school art competitions. There was a sense that this infrastructure, as symbols of modernity and top-of-the-line technology, was part of a national effort to prove that Singapore had a future – or, rather, that Singapore was the future, and that we were all in this together.

The past 5 years saw massive changes in my country’s skyline, population makeup and politics, all of which I am grappling with as a returnee Singaporean. For me something changed when the casinos were opened. I’ve been down by Marina Bay quite a few times now, and I especially enjoyed the iLight festival, where this city really did seem like something out of a scifi movie set, only real. But there is something disconcerting about the fact that our most iconic building is not an opera house, not a national stadium, not a government building, but a casino which bars locals from entering, built for the cynical purpose of milking superrich foreigners to increase the GDP. Can someone who believes gambling is a vice really feel national pride in something like this? I know I feel distinctly uncomfortable when I look at those three slender columns and the ship-like sky garden linking them. Many of my friends from overseas have enjoyed the spectacular view from the top in the infinity pool, but something still restrains me from paying the $20 to enter the sky garden. Somehow, I don’t want my money to go to a company that makes money off other people’s misery and addiction, even if I’m not directly spending it in the casino.

In a week or so another spectacular national development will be unveiled – the supertrees, also in the Marina Bay area. I’m a little more enthusiastic about these, since they also appeal to my geeky side. The supertrees cost $1 billion, and are touted as an amazing man-made imitation of nature, a leap forward in ecological architecture. While I will definitely be checking them out, I can’t help but contrast the construction of the supertrees with the destruction of Bukit Brown, a natural secondary forest, rich in biodiversity, where human heritage and ecology mingle seamlessly.

While watching the screening of Tan Pin Pin’s documentary Moving House at NUS yesterday, I was hit viscerally by the high human cost of national development. The sight of aunties and uncles praying to their ancestors for forgiveness before plunging their hoes into their parents’ graves, the half-curious, half-fearful peering into the grave to see the blackened, shrunken bones of the loved ones they buried some twenty years ago, and the uneasy feeling that their ghosts may be unhappy at these developments were both difficult and fascinating to watch. I think we Singaporeans are no strangers to “sacrificing the small me to complete the big we” (牺牲小我,完成大我). The sort of boh-pian stoicism, the black humour in the “can’t be helped, government needs your land, sorry sorry” explanations offered to the ghosts, are all deeply familiar and endearing, resignation tinged with the tiny sting of resentment.

But the thing is, we are able to swallow this resentment as long as we see the point of the sacrifice. The danger comes when national development is seen to be benefiting not citizens as a whole, but a small, privileged group, which, furthermore, may not even be primarily Singaporean. Yes, the supertrees will be open to the public – the $1 billion is not going to finance a private garden. However, they are located in the Marina Bay CBD area, enhancing the million-dollar views of the skyscraping buildings and condos in that region, and I’m willing to bet that the average heartlander will probably not make the trip down to see them all that often. Bukit Brown, on the other hand, is a far more humble site, though occupying some pretty prime land (next to the exclusive Singapore Island Country Club). It is a sacred site for veneration of ancestors, a rich source of historical information as well as biodiversity. Furthermore, its destruction (and so, the loss of historical memory) is irreversible – it’s not as though we can simply transplant the gravestones somewhere, or preserve the material culture without destroying it.

The truth is that much of the frustration I sense from the people who have relocated, exhumed graves, or had their land repossessed for the sake of “national development” is that simply not enough information is given to explain why their sacrifices matter, and, crucially, what they (and people like them) are going to get out of it. In other words, the cost-benefit analysis, while a process transparent to policymakers, is largely opaque to those affected. Perhaps the average Singaporean would be more willing to relocate because an MRT station needs to be built, rather than a highway, since he may see the MRT as a more egalitarian infrastructure project compared with a highway that he associates with cars (which, due to the high cost of COEs, are out of the reach of most Singaporeans).

Funnily enough, I find that now I have returned, my sense of national pride has shifted from the nation-building projects to the amazing growth of civil society I’ve witnessed from afar in the last few years. I am amazed at the volunteer spirit of the “brownies”, the way they have set out to teach other Singaporeans about their heritage and history and ecology. While the building projects are monumental and aspirational, the movement to preserve Bukit Brown’s heritage is nostalgic and humble, but also noble in its insistence that every pioneer buried there matters, and offers a glimpse of life on this island as it once was, a piece of history that, once destroyed, represents a loss to all of us, because our own understanding of ourselves would be that much poorer. The narration of the past is just as important as the building of the future. We are not rootless creatures. Although our nation may be young, each of our family histories reaches as far back into time as anyone else’s, no matter what our nationality, and it is truly up to us to preserve or discard these pasts.

Whatever the outcome at Bukit Brown, what is remarkable about the movement that has sprung up around it is that dialogue has opened up in ways unimaginable just a few years ago. Although activists may say that the government has been unresponsive, and civil servants may be wringing their hands at the unexpected “trouble” activists have given them, the truth is that the level of dialogue and collaboration has far exceeded any other civil society case in recent memory, and this can only be a good thing, as the government learns how to communicate its plans and decision-making processes better, and civil society gains more experience and tools in making the wishes and aspirations of Singaporeans known.

After all, a sense of national identity needs to come from the citizens themselves, rooted in our culture and our history, because in our democratic society sovereignty rests with the citizens, and legitimacy rests with their elected representatives. It is our shared past and our shared future that makes us Singaporean, and if we don’t stand up to define it, no one else will.

Judith’s other pieces on Bukit Brown can be found here and this one was written after her first visit to Bukit Brown

The Purpose of Keeping Heritage sites is to Preserve the Physical Linkage between the Present and Past

When the relevant authorities were planning for the cemetery to give way to the highway, did they know the historical value of Bukit Brown? Or was it after the researchers and the public’s strong interest and views that they suddenly realised the importance of this site? If this is the case, it reflects a deeper layer of problem: do the upper echelons of our government officials seriously lack historical and cultural conciousness? Today Bukit Brown is affected, who is to say a similar problem will not happen in future?

More than 50 – 60 years ago, scholars like Tan Yeok Seong and Hsu Yun Tsiao did indepth research of Singapore heritage sites including cemeteries, and they also inspired later generation scholars to conduct more research.

Everyone knows that History is ever continuing, and we make use of the past to shine a torch for the future. The 19th century German philosopher Hegel once said, ” What we can see now is but the fruit of the past, and what history tell us is invariably to preserve the things left behind from the past. Hence keeping track of the development of history is like a water current, the further out it can flow, the more volume it can gather, and the more content it can generate.

The importance of preserving heritage sites is to keep the physical linkage between the past and the present. If we destroy each and every heritage site, it means destroying the links between the past and the present, it means cutting off the roots of our present generation, so that if the latter generations would like to know how their ancestors travelled the path before, they would not have the physical evidence to substantiate it

Continuous gathering of history knowledge and research should be the mission of our education sector, but alas this is where the weakness of our Singapore education lies. We should build upon the foundation of the past research done by our predecessors, expand and upgrade them to the next higher level.

Translated by Raymond Goh extracted from the article by Han Tan Juan

Original Article

早报网–从恒山亭到武吉布朗

(2012-05-31)

韩山元

… 开门见山

笔心

保留古迹的意义就在于保留古与今的一个实体的连接点。

武吉布朗坟山因为当局要修建高速公路,要把其中数千座坟墓清

远在武吉布朗之前,新加坡开埠初期有座大坟山在恒山亭后面(

碧山也是历史超过百年的广东人在本地最大的坟山,1819年

当年这些坟山被铲除,也曾有人提出异议,表示惋惜,但是其声

有关当局在考虑修建高速公路,须叫古墓让路时,事前知道不知

早在五六十年前,陈育崧、许云樵等学者对于新加坡的古迹(包

众所周知,历史是有延续性的,是承先启后的。19世纪德国哲学家

保留古迹的意义就在于保留古与今的一个实体的连接点,如果将

历史知识与研究也应该有延续性,历史知识的延续是教育界的任

Memories – Myths

Zaobao, March 25, 2012

Extract:

Art Festival General Manager Low Kee Hong : The pace of our development is getting quicker, every generation needs to preserve their memories, from the Railway Station, Methodist Girl School old school site to Bukit Brown Cemetery. But finally we are not unable to keep these environment, only preserve these memories in digital photographs or in our memories. But will these memories of ours became myths, lost poems or finally lost? He asked.

Memories, are what we seek for our individual spiritual existence, what is ironic is that when we want to build our future, we have to give up our own individual existence and become wandering souls.

That day, I stood by the cemetery of Shuang Long Shan, reminiscing of the distant legends of Lanfang Republic, and the thoughts flowed back of what Tan Chuan Jin said in Parliament using the words of Lim Kim San :”Do you want me to look after your dead ancestors, or do you want me to look after your grandchildren?” My heart could not but felt spasms of nerve pain…

by Chew Boon Long – Zaobao reporter

周文龙:记忆迷思

(2012-03-25)

漂流记

多亏徐家辉即将在新加坡艺术节演出的新戏《兰芳记》,否则我大概

已听说这坟场的风景奇特,但真正走进去,我还是觉得震撼莫名

双龙山坟场位于应和会馆的嘉应五属义祠后。虽说是山,但它并

这坟场所处位置也非常有意思。它的前方是联邦路的旧车场,后

一个象征死亡的坟场,却位于一个民生力量蓬勃的邻里,使到双

参观坟场那天,徐家辉解释着这坟地的历史背景时,组屋区就忽

严格来说,徐家辉这位青年艺术奖得主的新戏《兰芳记》,与双

根据了解,兰芳国全称“兰芳大统制共和国”,是1770年到18

罗芳伯具有政治才能,而且胸怀大志,领导当时南来的矿工们,

值得一提的是,兰芳共和国像新加坡,有着相似的地理面积、政

兰芳共和国历经10名领导人,建立107年后,终因国小力弱

这传奇也为徐家辉开启创作灵感。他大胆地奇想,兰芳国子民会

历史可以重建?记忆情感可以创造?这想法乍听有点不可思议,

今年新加坡艺术节主题为“迷思”,所谓迷思,指的是一些十分

艺术节总经理刘祺丰说,现在城市发展越来越快,每一代人都强烈

“可是我们这些记忆,最后会成为迷思、迷诗,还是迷失呢?”

记忆,原来是我们所要寻找的个人存在的精神灵魂,令人感到反

那天,我站在这双龙山坟场,遥想着兰芳国传说,然后又想起前阵子

(作者是本报记者)

Notes:

Lanfang Republic was the first Republic in Asia, set up in West Kalimantan in Indonesia, and was established by a Hakka Chinese.

Shuang Long Shan is a Hakka Cemetery situated near Holland Road Singapore, founded in 1887 to meet the burial needs of Ying Fo Fui Kuan, a Hakka clan association. Shuang Long Shan means Twin Dragon hill, in reference to the two hills in the vicinity of the 100 hectare land, thought to resemble reclining dragons.

Researchers are trying to find the links of our cemeteries including that of Bukit Brown to that of Lanfang Republic.

By Ng Yi Shu writing for The Online Citizen

The debate with regards to Bukit Brown had raged for close to a year. With LTA’s and MND’s go-ahead on the eight-lane highway and the call for moratorium on the highway gone unheeded, there is nothing the NGOs can do today to stop the destruction of our heritage. But with all honesty, will we remember the our ancestral heritage and culture?

Will we even care? This is a hard question that no one wants to answer, but still, it beseeches an answer. This is not a question about policy nor governance. This is a question about our society, identity and narrative in general. This is a hard question to answer.

It was only the destruction of the old National Library building that sparked the debate to determine which of the two important matters of urban development and heritage preservation was more important in our society. Personally, I am too young to remember the destruction of the old National Theatre, but I do remember as a young boy reading that the government was intending to destroy the old National Library and that some commemorative red bricks from the building would be sold to heritage enthusiasts. In retrospect, I understand why people chose to pay money to purchase a piece of history about to be destroyed – because a picture of a place, though it speaks a thousand words, cannot compare to the experience of a place humans remember.

That is the same reason I took the chance to visit my great-great grandmother’s grave at Bukit Brown. My family is lucky that the grave is a fair distance from the highway and that it would be preserved.

Until the next development comes along.

Fact is, many of us do not remember the past. Many of us chose to forget the stories we have been taught since young: that of the first pioneers of Singapore, what they had built and the traditions they practiced. I am also guilty of the same thing: my understanding of old Chinatown came from a museum trip and a trail around the area. I would have never visited Bukit Brown if I did not know of the personal connection my family and I had of that area.

In my personal opinion, forgetting is not a sin. The circumstances that made us forget were understandable – we were a young country with dreams – dreams that we would be wealthy enough someday. These same dreams took us overseas – to study, to work, or for some, to sightsee. These same dreams brought back other cultures. Our open nature allowed for a melting pot of cultures to happen. Then, technological advancement came, accelerating this melting pot. We yearned for Western modernity. We worked for it. We became wealthy as a nation. In the end, there was neither time nor interest in our heritage or culture.

Then came the great privatisation of our media and the introduction of cable TV. The transformation of the then Singapore Broadcasting Corporation into Mediacorp today was hailed by many back then as a move to increase of broadcasting freedoms. However, a culture of self-censorship ensued. This, coupled with our yearning for other, ‘better’ cultures caused Singaporean media to be overlooked. Affluent viewers purchased alternatives from other countries, which created huge followings – that of JPOP and KPOP.

But, will we remember?

Politically, yes. The Bukit Brown Highway will remain a sore point. Citizens had many concerns – ranging from how the development of Bukit Brown would allow for more foreigners to come here to the environmental and ecological impact. Others took offence to the preservation of SICC and questioned the reasons why the country club for the wealthy was not spared. The decision to build the highway will, to some, represent the indifference the government has towards the people. The controversy will raise into public consciousness the importance of tradition and culture.

But such a negative event should not be the trigger for us Singaporeans to start caring about our roots again. In fact, the onus should be on us to explore, to see and to experience our heritage. Those that have been kept – the Chinatown shophouses, Sri Mariamman Temple, Masjid Jamae… the list goes on. The onus should be on us to maintain the emotional connection we have to our past. It is, after all, our choice to remember; our choice to be rooted; our choice to belong.

Recent Comments