by Catherine Lim

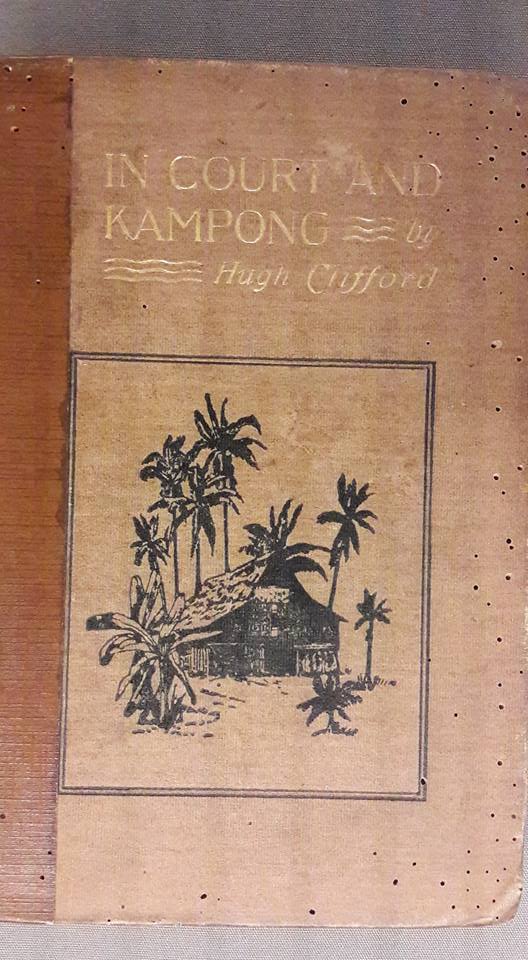

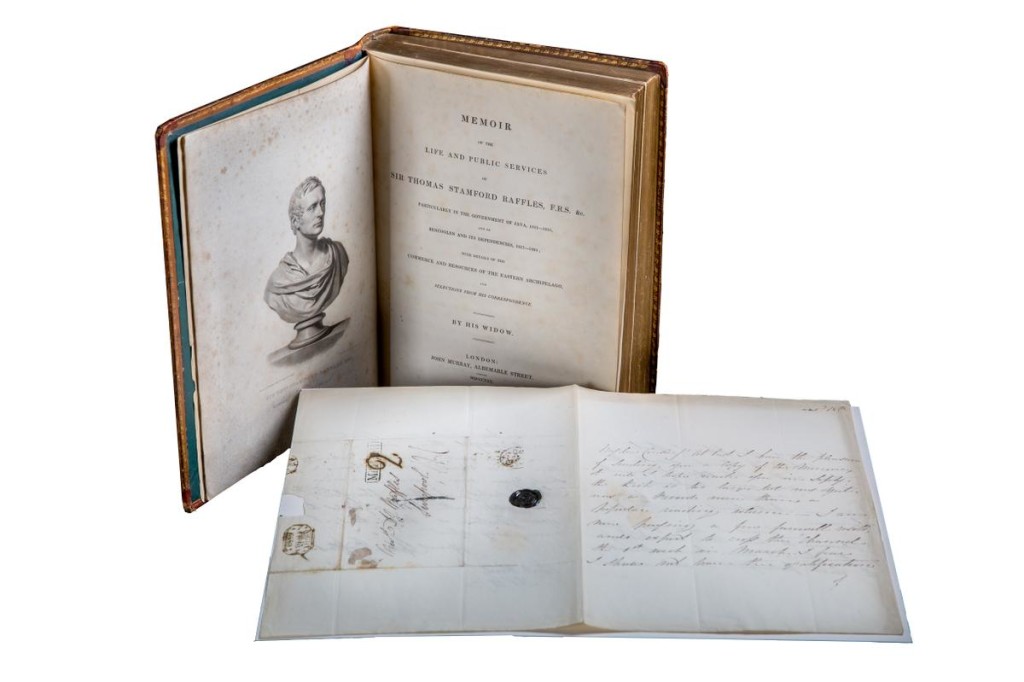

Considered the foremost authority on Raffles, the National Library Board has acquired the collection of Dr. John Bastin’s more than 5000 materials. 38 of which have been curated for public viewing on the 13th floor.

The exhibits both showcases and makes accessible NLB’s existing Singapore and South East Asia Collection which “form an important nucleus of works on early Singapore. “ The rare materials collection is conventionally the preserve of academics, perhaps perceived as” high brow” located as such on the 13th floor.

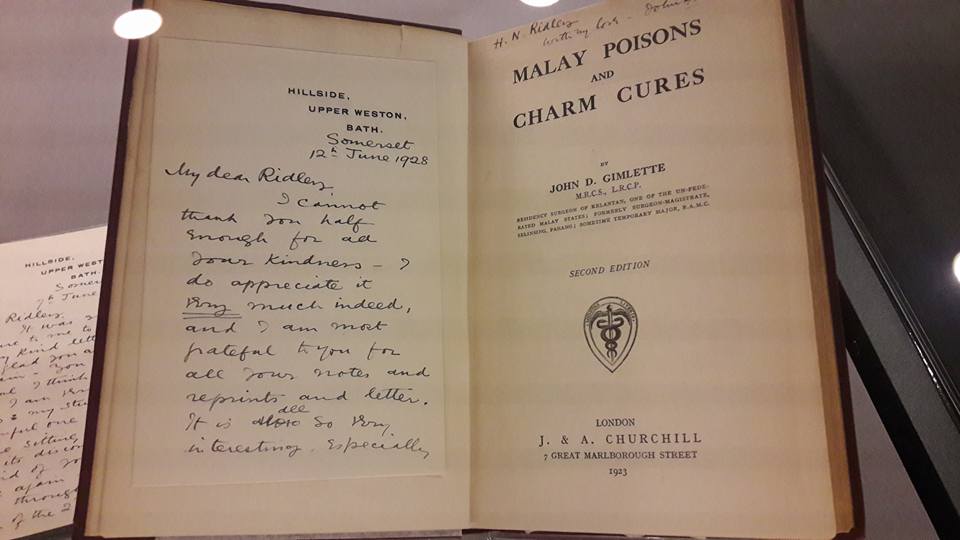

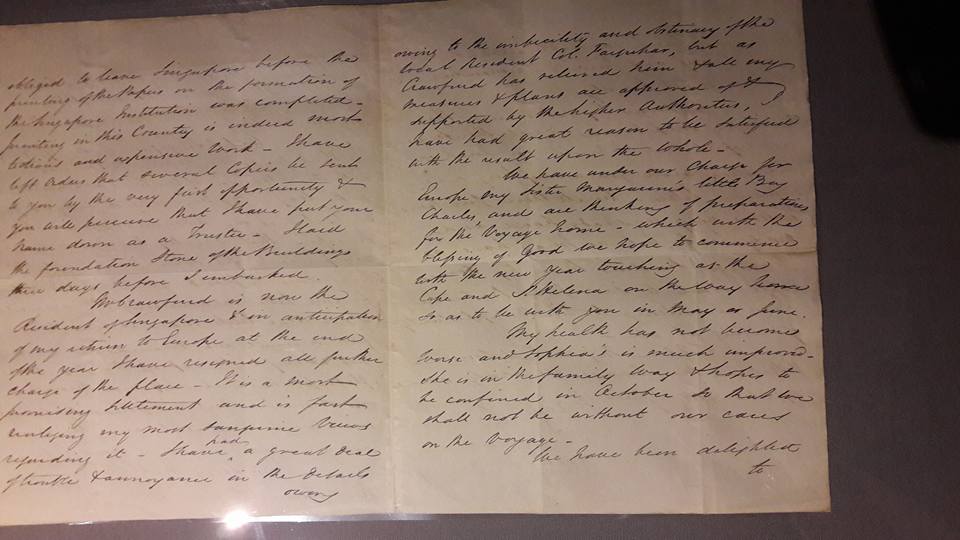

But this collection is curated with ordinary Singaporeans in mind with both the personal – a hand written letter by Raffles to his cousin which more than hints at his displeasure with Farquhar – and the quaint – a book on Malay Poisons and Charm Cures – to the spiritual – an almost complete Malay translation of the the Anglican Common Book of Prayer.

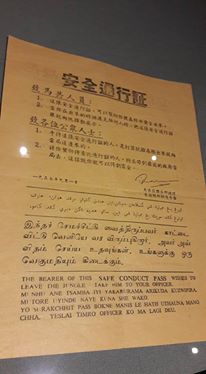

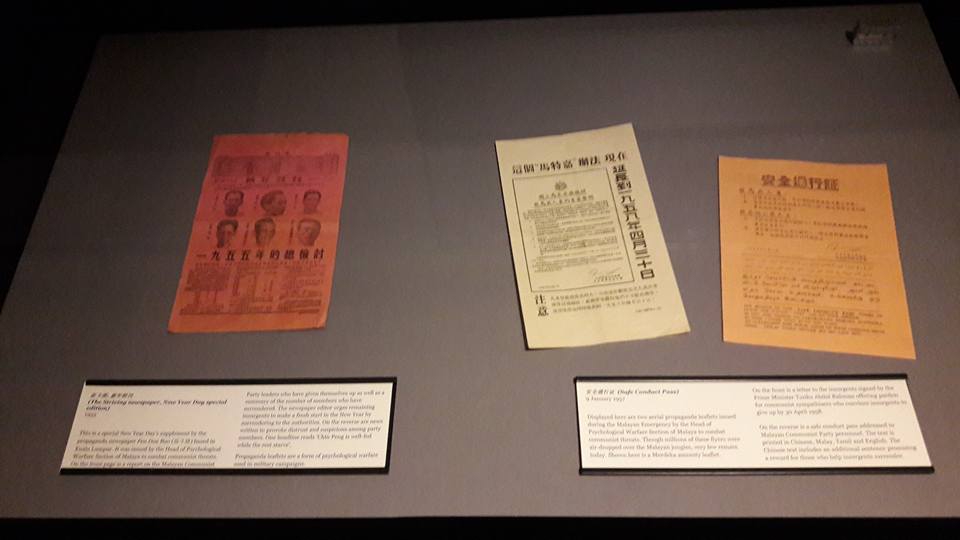

But the highlight must surely be the leaflets which were air dropped in the 50s at the height of the communist insurgency in the jungles of Malaya, in an attempt to “persuade” – both by threats and propaganda – insurgents to surrender peacefully. These leaflets dropped by the thousands and commonplace then, have become rare. I have seen them once in a private collection. The NLB rare gallery showcases three pieces.

A 1955 Chinese New Year “special” designed to tugged at the heartstrings and homesickness at a time of celebration (photo Catherine Lim)

Leaflets in 4 languages which provided “safe conduct” upon surrender. An indication that the communist insurgency had support from all ethnic groups ? (photo Catherine Lim)

Other Highlights:

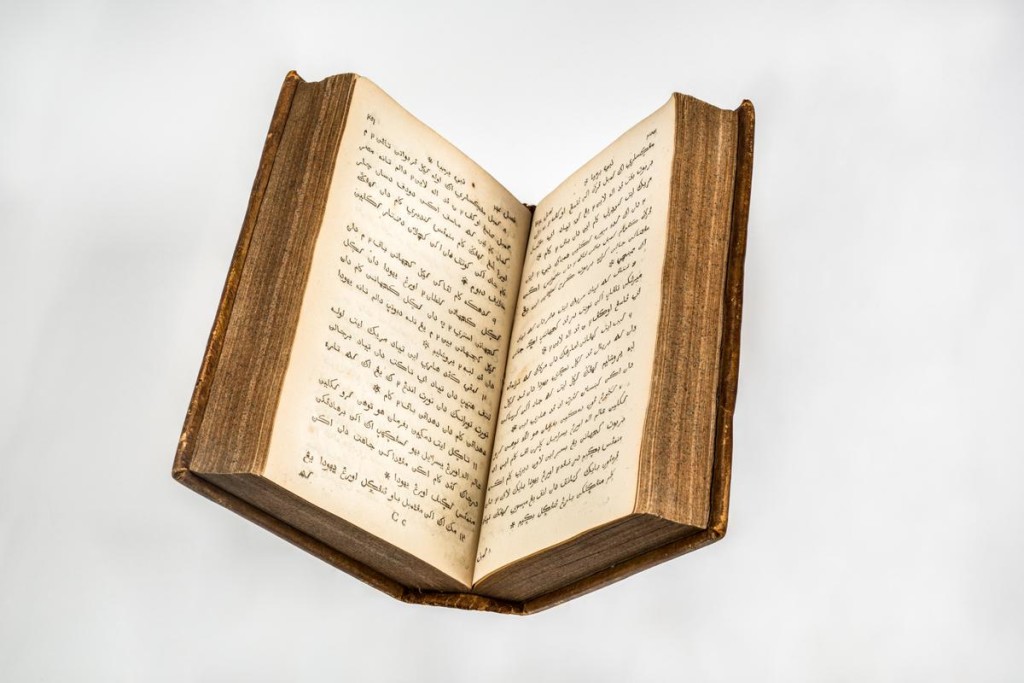

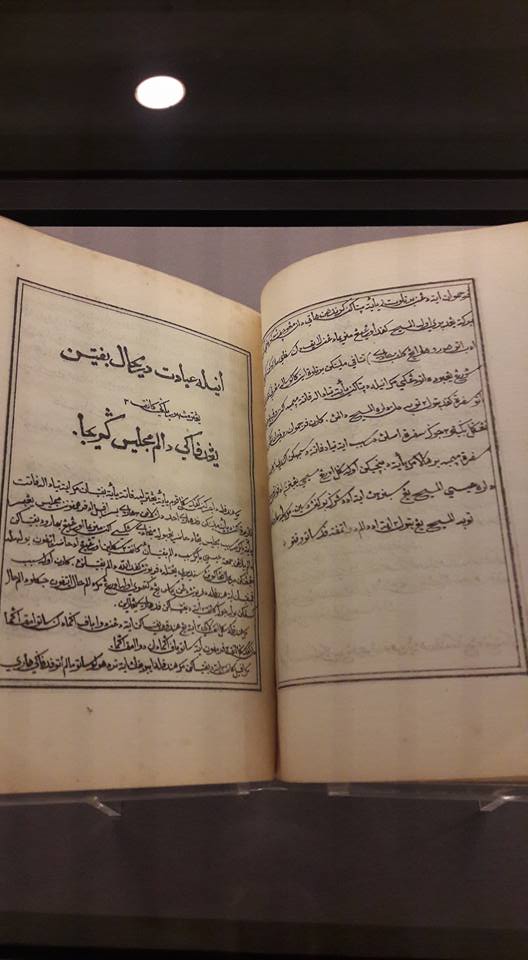

Treasures of the Rare Gallery – Al-Qawl al-atiq iaitu segala surat Perjanjian Lama ,Old Testament Bible in Malay (photo NLB)

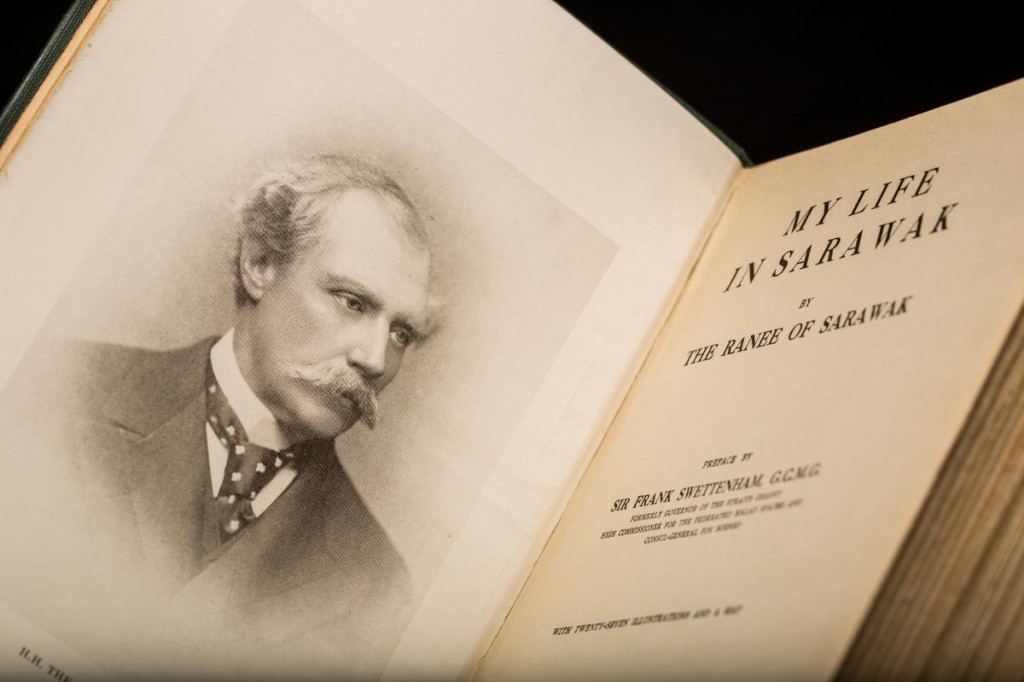

Exhibits on Java, Sawarak , Sumatra written by the “colonial masters ” stationed here, a reminder that Singapore was part of the “Straits Settlements”

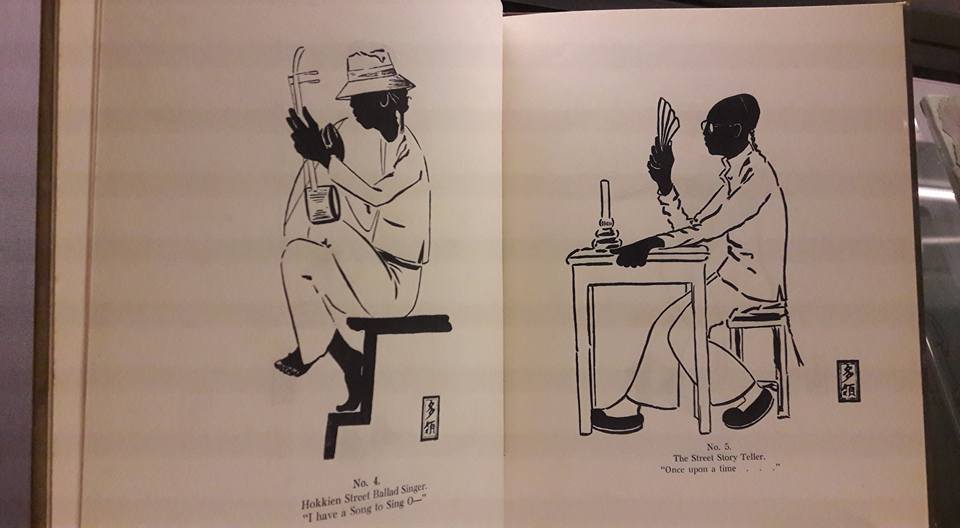

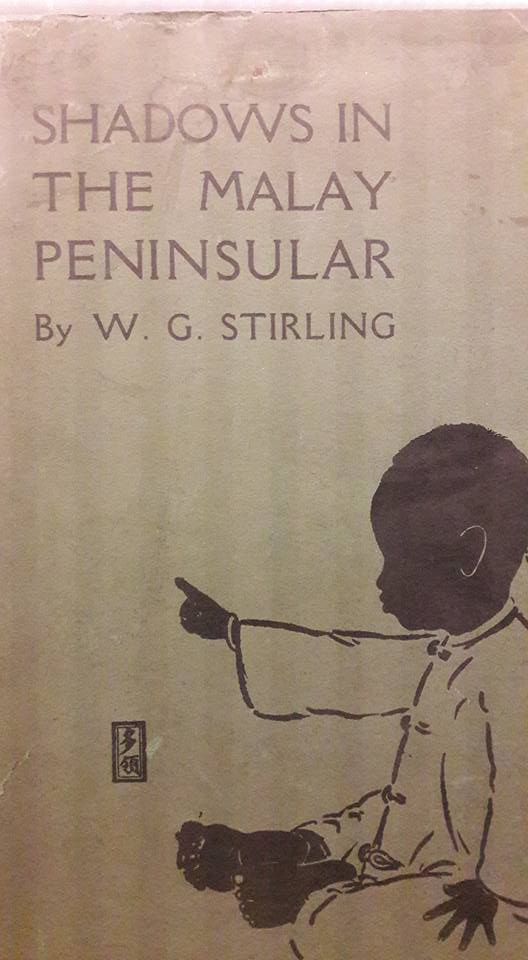

Thirty-two such silhouettes of different types of Malaysian people of the 20th C from “Shadows in The Malay Peninsular” by W.G. Stirling, London 1910 (photo Catherine Lim)

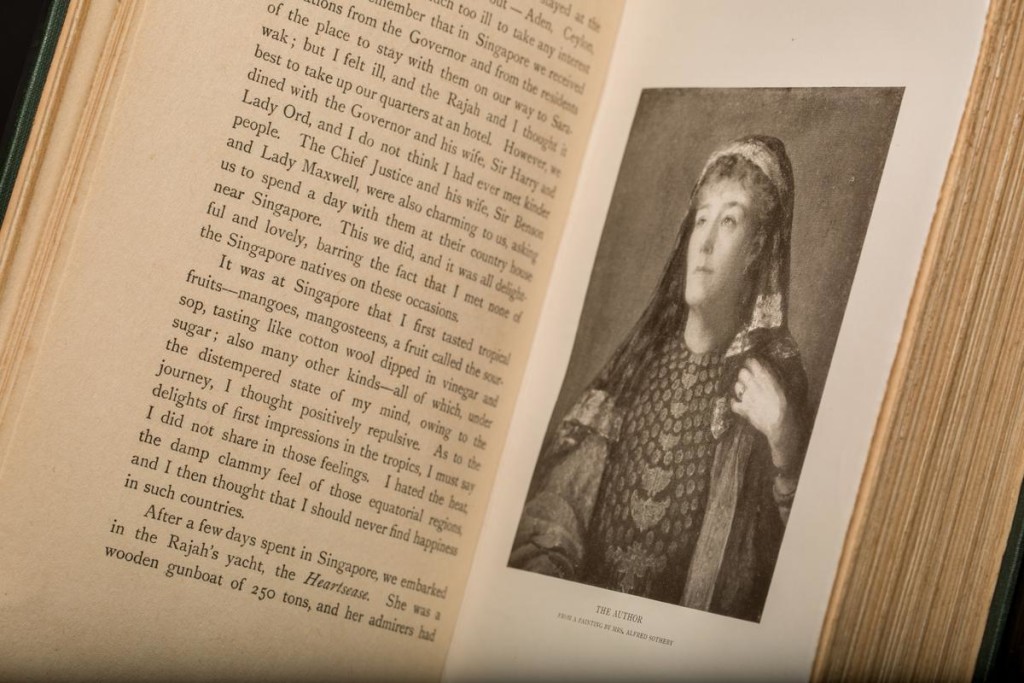

Written by Margaret Brooke “Ranee of Sarawak (1849-1936) and consort of the Sir Charles Brook. The copy on display establishes the social connection between the Brookes and Swettenham (Governor of the Straits Settlements). Swettenham refers fo Ranee as “Margaret darling” in 2 handwritten letters (photo NLB)

Expressing Raffles passion for the biodiversity of the region.

From “Descriptive catalogue of the Lepidopterous insectsnby Thomas Horsefield London, 1828/9 (photo Catherine Lim)

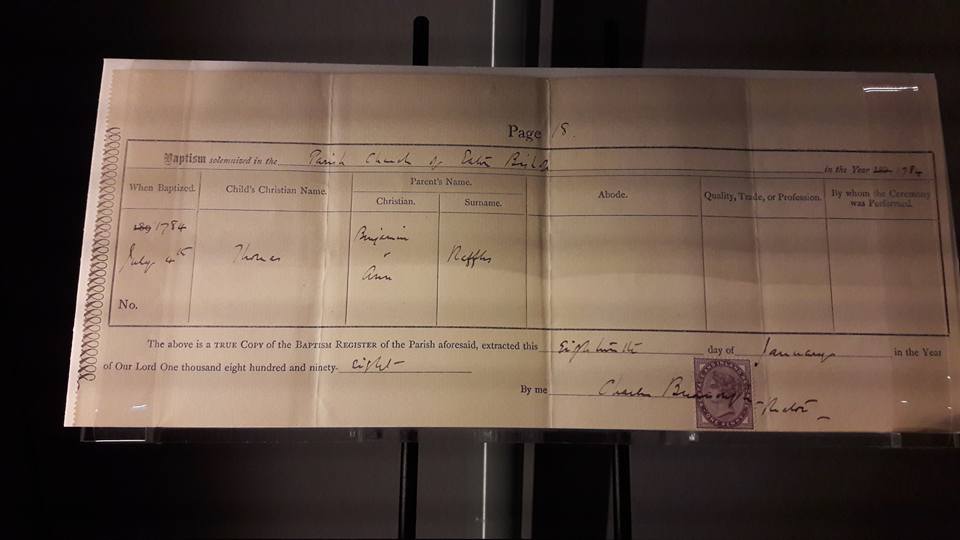

And lets not forget, exhibits which clearly reminds us of the collector’s primary interest, Raffles himself.

Of interest for further study an exhibit of : a bill introduced to the British Parliament on 18 June 1824 to ratify the Anglo-Ducth Treaty of 1824 which concluded longstanding territorial and commercial disputes between Britain and Netherlands. A valuable source of information of how the two rival colonial and maritime powers decided on how to carve out their colonies in the region

As a collection, its importance is to give visitors a flavour of our past, providing historical context in print that covers different facets of political, social and community engagement at a personal level.

If there is anything more the NLB can do to get more Singaporeans to “embrace” the rare collections , is perhaps for this collection to serve as an inspiration for other activities which could revolve round art and story imagining of a past which helped defined who we are today.

Guided tours of this collection will be held monthly between July and December. Do check listings here

———————————————————————————

Catherine Lim is co-editor bukitbrown.com

Moved by “unseen” hands, the deities which used to be located at the former entrance of Bukit Brown Cemetery, were also moved when the pillars of the gates were relocated.

They now have a brand new shelter – we have been informed by a credible source – which was “upgraded” by Fusion Clad Precision (of their own initiative), the company commissioned by the National Heritage Board to restore the gates.

Photos captured by Brownie volunteers help document the “sheltering” of the deities which we believe are the efforts of a community who work behind the scenes.

An unsheltered Earth Diety also known as Tu Di Gong or Tua Pek Kong taken sometime in May 2016 by Bianca Polak before a new shelter was put in place.

Guanyin captured in 2015 by Darren Koh before the gates were moved. According to Darren, Guanyin is a heavenly deity unusual for a cemetery which is traditionally the purview of the Earth Deity . But then, this is Guanyin who will take any form necessary to help humankind.

Fast forward to June 2016, and the altar, now relocated along with the gates, have now been “regularised” with the disappearance of the Guanyins, and the installation of a “new” Tua Pek Kong flanked by two Datuk Gongs, one on each side. (photo by Darren Koh)

The “upgrade” by Fusion Clad include the paint job and sensor lights, shelving and a dry place to store joss sticks and with even a lighter in place (although the last may have been placed there by others for convenience). The community who work at Bukit Brown have been observed by Brownies to pay respects before they start each construction work day as a mark of respect and request blessings for a “safe environment”

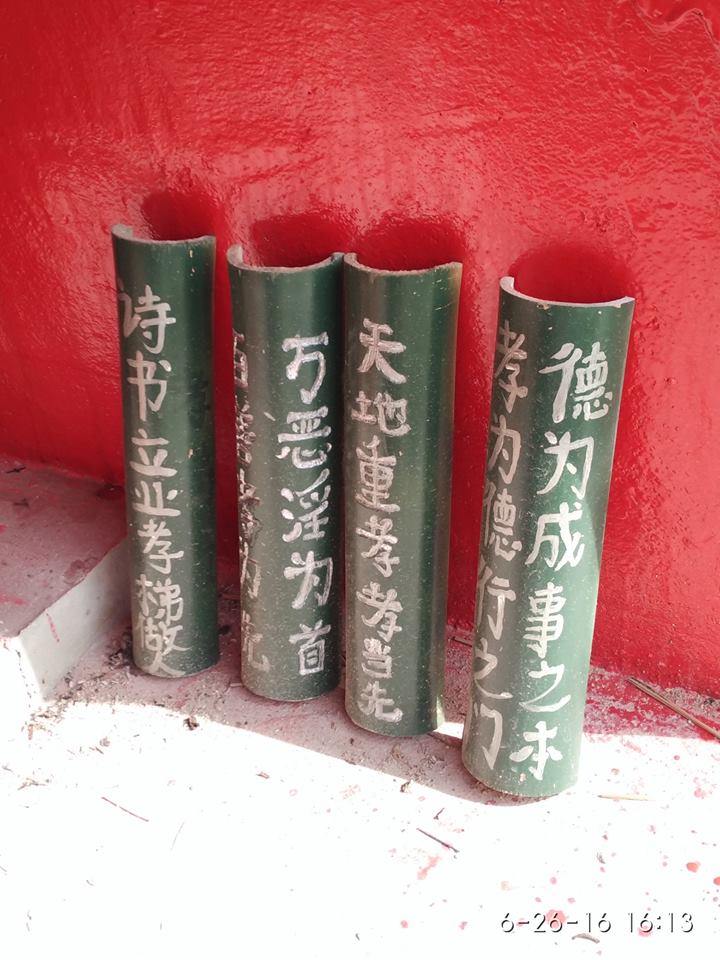

Together with this new shelter interesting is the emergence of the green bamboo inscribed with felicitations – not our local tradition, according to Darren and he wonders wonder what is the story behind them (photo June 2016 of bamboo inscriptions on left side of altar by Darren Koh)

Change is inevitable; Memories endure; The tangible is the gateway to the intangible.

A closeup of the iron wrought design detail shows what uncannily looks like a bat . In Chinese “Fu” is a homonym for fortune. (photo Chua Ai Lin)

The iconic gates of Bukit Brown which had stood in the same spot for some 90 years were removed on September 2015, and have been undergoing the delicate process of refurbishment since January 2016. It is expected to be relocated back in June 2016 and enjoined with the pillars which have already been relocated to the new entrance.

Members of All Things Bukit Brown and the Singapore Heritage Society as part of the working committee on Bukit Brown chaired by the Ministry of National Development were invited to a private viewing of the work in progress in March. The refurbishment is being undertaken by Fusion Clad Precision who were hired by the National Heritage Board.

SHS, NHB and ATBB representatives at Fusion Clad Precision premises in March 2016 (Photo Chua Ai Lin)

According to a Straits Times report published on May 3, 2016 “Iconic Gates to Greet Visitors to Bukit Brown Cemetery Again” :

“The refurbishment, which started in January, has five core steps. Rust is first removed before coatings are applied to reduce future corrosion.

The gates’ lock and latch components as well as lampholders are then repaired before missing parts are replaced. The last step is to reinforce the gates’ structural integrity.

The team, comprising four master craftsmen and three other members, is at step two of the process.

Its managing director Teo Khiam Gee said the gates need a lot of attention as well as “the human touch”.

“Skilful hands are important as the parts are in varying states of disrepair. Its original state was very fragile. It is like handling a baby,” he said.

The structure is made up of parts, such as a pair of cast-iron gates through which cars used to pass, two side gates for pedestrians, and four free-standing square columns.

It was likely prefabricated in Britain and shipped to Singapore. Its square columns were cast on the spot.”

The report adds:

“NHB’s assistant chief executive of policy and community, Mr Alvin Tan, said retaining and refurbishing the gates are important as they “provide a sense of arrival to the cemetery and preserve a sense of continuity for visitors and interest groups”.

The refurbishment is an initiative of a multi-agency work group chaired by the Ministry of National Development. It includes NHB, the Land Transport Authority (LTA), and civic organisations All Things Bukit Brown and the Singapore Heritage Society (SHS).

The effort is guided by conservation best practices shared by SHS. The heritage board also has its own in-house metals specialist, Mr Ian Tan, manager of the heritage research and assessment division.

When ready, the gates will be painted black – a common colour for outdoor use.”

You can find is a step by step graphic representation provided by ST on the process here

NHB produced a short documentary on the removal of the gates and the relocation of the pillars which supports it:

We honour the memory of the gates in our recently launched book WWII@ Bukit Brown.

“In the end we will conserve only what we love; we will love

only what we understand; and we will understand only

what we are taught.” (Baba Dioum, 1968.)

A quote by the Guest of Honour Senior Minister of State , Desmond Lee (National Development and Home Affairs) in his address , captured aptly the journey of the Bukit Brown community leading to another milestone in what has been dubbed ” a movement” with the launch on 16 April, 2016 of the book WWII@Bukit Brown – a collection of essays, poems and stories from the community of Brownies and descendants.

In his speech, Minister Lee recounted his first guided walk at Bukit Brown Cemetery with his constituents :

“During the visit three years ago, we learnt about the history and heritage of our pioneers from the stories shared by the Brownies.

Over the years, we have all been very impressed by the passion demonstrated by the Brownies, as they have contributed so much of their personal time, personal energy and expertise to research, document and share the history of Bukit Brown with the rest of us in Singapore.

They are an example of what the community can do to connect with, and to celebrate our history. But if we reflect on it, although Bukit Brown is a cemetery, their work is so much more than just about the past. It is also very much about our future.

The research that the Brownies did led descendants to approach them for help to identify their ancestors’ resting places, and from there, an opportunity to open up conversations about their personal and family stories, which they then shared for the benefit of posterity.

I understand that some of the descendants are here. Some of your stories and stories of your forefathers have made their way into this book. This book is a testament to the hard work and effort the Brownies had invested over the years.”

We were also honoured to have descendants among the contributors to the book grace the launch and they included the descendants of Tay Koh Yat, Tan Ean Kiam, Cho Kim Leong and Tan Kim Cheng.

Tan Keng Leck, grandson of Tan Ean Kiam with Minister Desmond Lee. The Tan Ean Kiam foundation is also one of the sponsors for the book (photo Lawrence Chong)

Claire Leow (Editor) with the youngest and oldest grandsons of Tay Koh Yat showing them the chapter on their grandfather.(photo Carolyn Lim)

Jenny Soh in maroon top is the niece who was saved by her Aunt Soh Koon Eng who died during a bombing raid at their home in Geylang. (photo Carolyn Lim)

Among the guests who attended, the Australian High Commissioner Philip Green and his partner Susan who have been guided by Brownies (photo Lawrence Chong)

The Editorial Team (minus 2, Yik Han and Raymond Goh) with Minister Desmond Lee. L-R Catherine, Claire, Simone, Peter, Minister Lee, Bianca, Fabian, Chyen Yee, Charles (photo Lawrence Chong)

It was an occasion for connections and re-connections.

SHS President Chua Ai Lin with Dr. Tan Cheng Bock an old family friend and Alex Tan Tiong Hee who contributed a chapter in the book. (photo Lawrence Chong)

SHS President Chua Ai Lin, Catherine (editor) Kevin Tan (former SHS President and Editor of ” Spaces of the Dead- A Case from the Living 2011″) Minister Lee and Claire (editor) – Overheard, Kevin recounting to Minister it took 11 years to raise funds for the book Spaces of the Dead also published by Ethos (photo Lawrence Chong)

Descendant of Dr Lee Choo Neo – Singapore’s first female doctor – with CW Chan who contributed a profile piece of Lee Choon Seng – “oh to be a fly on the wall of this conversation” (photo Carolyn Lim)

Minister Lee meeting Jon Cooper who contributed a chapter to the book and recently launched his own book Tigers in the Park on the WW II archeological digs he conducted over a span of 6 years as part of the Adam Park Project

Jon, captivated the audience at the launch with his stories of the descendants and survivors of POW camps he had met in the course of his research (photos of Jon’s presentation by Lawrence Chong)

And finally a pictorial thanks to our sponsors in no particular order :

And as previously mentioned Tan Ean Kiam Foundation is one of the sponsors.

You can support funds for the book by purchasing a copy or more here

If you would like to bulk purchase books to donate to community organisations, drop us an email a.t.bukitbrown@gmail.com

And here’s a reminder of “who” this is all about:

“In the end we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand; and we will understand only what we are taught.” (Baba Dioum, 1968.) Photo Simone Lee

Acknowledgments:

To everyone who came, out heartfelt gratitude. To our official photographers, Lawrence Chong and Carolyn, thank you.

Look out for more stories about the launch and updates about the book in the blog under History : Books

Co Publishers:

Ethos Books and Singapore Heritage Society

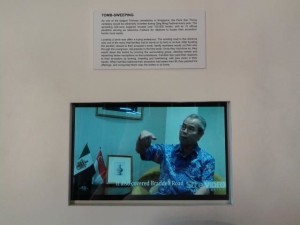

It’s the end of another weekend and rarely a weekend passes when Raymond Goh aka “Tomb Whisperer” is not to be found doing ground exploration and research at Bukit Brown, nowadays often with tombkeeper Soh who helps him bush bash and lends his knowledge of the grounds he grew up in.

Today’s sharing on his “finds” on the Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown FB group included a tomb “gift wrapped” in Peranakan tiles, a newly refurbished tomb ( more signs that descendants are returning) , a tomb with a story to be unraveled, and a tomb bearing 中華民國 – Republic Of China.

Unusually Raymond was also at Bukit Brown this Saturday (he splits weekend days between his family and his passion ) to meet an independent researcher who hopes to write an article on a prominent pioneer whose tomb Raymond had found much earlier and wanted to tap his knowledge

Then I learned that much earlier in the week, Raymond got up at 4 am one weekday morning so he could help facilitate a fervent request by an international documentary crew to film an exhumation at Bukit Brown. Exhumations are private family affairs and it was indeed a testimony to Raymond’s reputation for sensitivity and discretion in such matters that he was able to persuade family to allow for the filming and be interviewed.

All in a weeks work you could say for Raymond who has to juggle his passion with his career heading a multi- national healthcare company which finds him traveling on average once a month on business trips.

It is a passion which can be traced back a decade when he teamed up at the instigation of his younger brother Charles – who heads workplace safety and health at a Japanese firm – to explore and uncover the “lost heritage and history of Singapore”. The siblings have more than a blood bond, as they leverage on each other’s strengths. It was Raymond’s interest in Chinese and regional culture and history which Charles’ sought to complement his own skills in map-reading and understanding of title deeds and ownership.

Their decade of exploration and what they have uncovered including the community which has rallied around them was documented recently in a feature called Life Extraordinare

http://video.toggle.sg/en/series/life-extraordinaire/ep8/358863

The Goh brothers intrepid exploration of forgotten places – more often than not sited in thick forested areas – paired with their investigative work trawling the archives for maps and records, have helped Singaporeans connect to their past, and sparked personal journeys into the search for their roots for a new generation of Singaporeans.

The discovery of the grave of Singapore’s foremost Teochew pioneer Seah Eu Chin (1805-1883) by the Goh brothers in November 2012 is an exemplar of their commitment and passion, one with wider resonance in 2015.

In 2011, prompted by a request from a descendant of Seah who went to school with Raymond, they found a Straits Times obituary (1883) that described Seah Eu Chin’s funeral procession, from his home in North Boat Quay to his plantation in Thomson Road, about 4.8km away from town. From the description of the funeral procession, Charles extrapolated the approximate location from a 1924 map. But to confirm whether it was indeed the grave of Seah Eu Chin, what was needed was an understanding of the Chinese practice whereby family members of the same generation used the same characters in their names. And that was where Raymond’s interest in Chinese culture and tradition came to the fore.

“Knowing the generation name, which was certified in an imperial edict he found, helped him confirm that the grave he found on Grave Hill belonged to Seah Eu Chin”. ST Nov 28, 2012, Teochew pioneer’s grave found in Toa Payoh

Of the discovery, Dr Hui Yew-Foong, an anthropologist at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies and the appointed documentarian of Bukit Brown Cemetery commented, “This grave is of the same level of historical significance as the graves of Tan Tock Seng and Tan Kim Ching, and therefore serves as an invaluable part of Singapore’s heritage.”

For the Goh brothers it was mission accomplished. For the Seah clan, it was the beginning of the unravelling of familial connections lost after the devastation of World War II. Before the war, the 2,000-strong family of descendants spanning at least five generations had gathered regularly. The 130th anniversary of Seah Eu Chin’s death was marked at his grave site in 2013 a year later by descendants and members of the two Teochew Clan Associations he help found, the Po Ip Huay Kuan and Ngee Ann Kongsi.

For Sean Seah 39, a 6th generation descendant of Seah Eu Chin who took part in the memorial prayers, it was followed by a journey tracing the steps of personal history when he made a trip back to the ancestral home and villa of Seah Eu Chin in Yuepu village, Chaozhou province in 2014 which he documented in this video. https://vimeo.com/95650452

“When I was young, my father used to tell me stories about Seah Eu Chin. when I went to school, I learnt more about him, but many questions still lingered. When I gazed upon and touched the tomb of Seah Eu Chin, I felt a a tangible visceral connection to my roots and moved to embark on a quest for these questions to be answered, and so to the Goh brothers, I am grateful” – Sean Seah (personal communication)

Intrigued by this unearthing of history, in November 2015, the Goh brothers revealed the significance of two stone markers they found in MacRitchie area. One was inscribed with the words “Dare” in English and the other “Seah Chin Hin” in Chinese for Mr Seah’s plantation, as well as the stone and brick foundations of Mr Dare’s former home. “Dare” was George Mildmay Dare a former secretary of the Singapore Cricket Club. The two stone markers are discoveries which tell the complementary stories of the land, of our colonial past and our migrant pioneers.

The Goh brothers cache lie in ignominious stones, the kind you trip upon when taking a road less travelled but when examined closer becomes a doorway to our historical landmarks.

The curiosity as well as the passion for our history drives them to search on the ground as well as delve into archives for supporting evidence or clues. Charles was exploring the old forested area near Macalister Road when he stumbled upon a wall in the grounds of the Singapore General Hospital in September 2014. The National Heritage Board was alerted to its discovery by the Goh brothers and through further research, found that the remnants belonged to the New Lunatic Asylum which 128 years ago was revolutionary for its time, a period when strait jackets was more the norm. The perimeter wall was to allow patients to move about freely under protection. Within the grounds of the SGH carpark, which was undergoing development in 2014, was also the remnants of a burial site belonging to a Chua clan dating back to the 1860s, occupying a private strip of land then sandwiched between Tiong Bahru (New Cemetery) and Tiong Lama (Old Cemetery) that would have been referred to as Seh Chua Sua (Chua Hill) On a visit to the site led by Raymond and Charles organised by the Tiong Bahru heritage group earlier this year , participants found four gravestones cordoned off for protection in the midst of the construction site.

2015 is a significant year for the Goh brothers as it marks a decade of exploration of Bukit Brown Cemetery and the adjoining cemeteries which have become an important memory marker for Singaporeans.

It is what the Goh brothers have become most known for in the public consciousness, ironically because of the unexpected controversy which erupted in 2011 when the government revealed plans to build an 8 -lane highway across the last remaining Chinese cemetery, one with a history dating back to the 1800s. The Goh brothers had started to explore Bukit Brown as early as 2005, and uncovered the tombs of pioneers such as Cheang Hong Lim, Tan Keong Saik, Khoo Siok Wan, Seah Imm, Tan Ean Kiam, Chew Boon Lay, Chew Joo Chiat, Tan Kheam Hock – more than 30 pioneers to date whose names are immortalised in our streetscape.

By 2011, they had the best working knowledge on the ground of Bukit Brown which had closed in 1973 – the final resting place of an estimated 100,000 pioneers and whose terrain had become overgrown, the kind of challenging landscape the Goh brothers relished.

As descendants’ awareness of their familial obligations to claim and exhume their forebears grew, it was to the Goh brothers that they turned to unravel the clues to locate ancestors’ graves or other related information lost to time. Others, their interest piqued by the circumstances, started to trace if they had ancestors buried there, leading to even more leads to chase.

Many who requested help from the Goh brothers to trace their ancestors even mistook Raymond as being employed by Land Transport Authority to help them verify whether the graves of their ancestors would be affected by the highway. Both brothers were members of the Advisory Council on the Bukit Brown Documentation Project, a committee set up by the government in recognition of the heritage and historical value the cemetery. It was made up of stakeholders who could advise on documentation of the approximately 4000 graves which had to be exhumed to make way for the highway. Nonetheless, their endeavours were beyond the remit of the advisory council, and testament to the true value of the Goh brothers to the broader community.

It was this broader interest in helping descendants seek their ancestors, regardless if they were affected by the highway, that resonated with ordinary Singaporeans and residents.

Besides Seah Eu Chin, early clues in Bukit Brown also led to the discovery of Chia Ann Siang, who was not buried there. The discovery of Chia Ann Siang’s grave in a forested hilllock off Malcolm Road, also led to reunions and connections. Alphonsus Sng, 6th generation Chia Ann Siang writes,

” We were told growing up we were descendants of Chia Ann Siang on my mother’s side, but it was not until his grave was discovered by the Goh brothers, that we could confirm, from the names of his sons etched on his grave we were in fact descendants from his 3rd son Beng Chiang, who was my great grandfather on my maternal side. The reunion at the grave was a first in meeting cousins we never knew existed of my generation, descended directly from Chia Ann Siang. We have since kept in touch, exploring our shared ancestry together” – Alphonsus Sng (personal communication)

Raymond Goh estimates that he has helped to connect about 50 families whose roots are in Bukit Brown. But the Goh brothers’ contribution in a body of work that spans a decade is exponential.

Leveraging on their research, a community of volunteers came together in 2012 almost spontaneously and started conducting regular public walks in Bukit Brown to instill awareness on its intrinsic heritage and history, some later expanding on the research of the Goh brothers to conduct their own independent research. They became collectively known as the “Brownies” – a motley group from different professional backgrounds from lawyers to engineers, of different faiths, different ethnicity including a Sikh and a Catholic Indian. The youngest is below 30 of age the oldest, above 60. For them Bukit Brown has taken them to places outside of Bukit Brown and indeed out of Singapore to explore the history and heritage of our migrant roots, our diaspora. A handful have also joined the ranks of Raymond and Charles in helping to connect descendants with ancestors.

“2015, Singapore’s Jubilee, was a year to take stock of where we are heading, and where we came from. In this connection, very few ordinary Singaporeans can claim to have played as significant a role in helping us appreciate our past. Raymond and Charles Goh are arguably pioneers in their own right in exploring and sharing with the public the significance of cemeteries, particularly, Bukit Brown in linking the dots between the past and the present, the departed and those living

On a personal note, I have had the pleasure to be a former classmate of Raymond and we are both alumni of Gan Eng Seng. I was moved by the tour of Bukit Brown conducted by Raymond which culminated in homage paid at the tomb of our school’s founder. This reminded me of the Raymond Goh I remembered when he was a boy, a classmate with an enquiring mind, a strong sense of curiosity, who excelled in the sciences. I am proud that he has applied these skills in his Bukit Brown related pursuits, for he is an excellent detective and investigator of the past.” Khir Johari, Singapore Heritage Society, SHS Vice President (personal communication)

The Goh brother’s decade-long track record, and an undaunted and persevering spirit to a cause despite a lack of early support have been self-less. They have willingly shared their knowledge and skills and created space for other like-minded persons to follow in their very large footsteps. They have inspired other volunteers, but also a broader public, which has opened their eyes to alternative histories and an independent route of inquiry.

In the words of a recent reflection by journalist Lisabel Ting in the last week of 2015.

“Like a salmon swimming upstream, I think all humans have an innate desire to return to where we came from and to site ourselves in the continuum of history by knowing what has come before. …..This urge to return to our source may be particularly compelling for Singaporeans, especially the many of us who are culturally adrift and loosely moored to this island only by the strength of several generations.For the majority of us, whose parents and grandparents hail from countries across the ocean, our kin are scattered around the world, and may be culturally and linguistically distinct.Having a family tree on which to hang our heritage could, in an impalpable sense, provide a sense of deep-rooted belonging or affiliation which is sometimes missing here.” ST 29 December 2015 “ My surreal connection to my ancestral home”

Today 24 January, 2016, I came across another reflection which resonated ” We cannot protect what we do not know” and the Goh brothers have shared what they know and will continue to explore and unravel so we can also also embark on our personal journeys to learn.

“We cannot protect what we do not know”

The tomb of Wee Theam Tew is yet another significant discovery made by tomb whisperer, Raymond Goh in the Greater Bukit Brown. Wee Theam Tew was a lawyer and died at the age of 52 due to his failing health. His tomb has inscriptions in both English and Chinese, and a set of poetic couplets, which is believed to enhance the livelihood of the deceased’s family. This one reads:

坐山脈正派

向水源當長

添秀山為景

籌華地作玩

This is how one member of the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook community, James Koh translated the couplets to English and added his interpretation of the significance of the words :

The mountain sits with honorable aura

The river flows with abundance

The hills add charm to the landscape

The earth becomes pleasing to the eye with accumulated lustre

He adds that the couplets “represent the things which Mr. Wee wish to bestow on his descendants — reputable status, decent lineage and legacy, strong prospects, and a happy home.

What makes these couplets interesting is, in each sentence, there is supposed to be a stop after the first two words. For e.g., 坐山 ¶ 脈正派. But the second and third words actually form a noun which is related to Mother Nature — 山脈, 水源, 秀山, 華地. This, in turn, displays Mr. Wee’s brilliance in Chinese literature.”

We are assuming these were either written by Wee or chosen by Wee.

Do join the discussions in the Heritage Singapore – Bukit Brown Cemetery Facebook group page, a platform for all members like James Koh, to learn, as well as contribute and share their knowledge in all things related to heritage, habitat and history.

An update on this post as Jing Xiang has completed his Masters thesis

Abstract : Housed within Bukit Brown Cemetery are the many tombs of pre-independent Singapore pioneers with syncretic elements of a multicultural milieu. It remained a largely forgotten site except to families who visit the burial ground especially during the annual Qing Ming (tomb sweeping) festival.

In 2011, the state announced plans to redevelop Bukit Brown. Civil society groups, who saw the site as one rich in biodiversity and embedding an important historical past, contested the decision. This contestation rehearses a long-standing tension between heritage and progress in Singapore. This dissertation recasts Bukit Brown Cemetery as a highly charged site where notions of identity and belonging are latent.

The dissertation argues for an understanding of this forgotten landscape as integral to the Singaporean psyche of home and nation. Using Benedict Anderson’s concept of imagined communities and Henri Lefebvre’s spatial trilectics as its theoretical

frameworks, this paper outlines the spatial taxonomies present in Bukit Brown, and how identity is produced and anchored in those spaces. The inquiry unfolds on two scales: the first is a micro-territorial scale where the spatial practices of the individual and domestic unit are studied in relation to the tombs and myths found within and around Bukit Brown. The second one looks at Bukit Brown as macro-territory dotted with cultural anchors signifying collective histories.

Taken together, these two scalar frames reveal the complex structures of individual and collective identity, and how such structures are still actively forming/reforming at the Bukit Brown Cemetery.

His thesis can be found here

=========================================

First Published on the blog on 20 August, 2014

Some elements in the drawing are all too familiar landmarks in the cemetery, while others suggest hidden secrets, or things that,as of the present moment, has disappeared due to the roadworks. The drawing straddles between what is real and what is imagined, what is there and what is not there, or ‘not there’ because we can’t see it (yet) like other intangible (forces or) values of Bukit Brown.

(please click to view and appreciate full image)

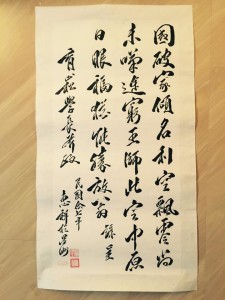

When the country is broken and families are upturned, fame and fortune mean nothing.

Although I am forced to wander, I am not yet lamenting that our cause is hopeless.

My eyes may be luckier than that of Lu You, for I may (live to) see the day when the righteous army sweeps north and pacifies the central plains

[i.e., when we have driven out the Japanese].

Update: For the latest on which library the exhibition has moved to please click on this FB page link

Becoming Bishan: A Heritage Exhibition

What is Bishan? A concrete jungle of million-dollar HDB flats? The futuristic, award-winning architecture of SkyHabitat and Bishan Library? Or even the bustling activity of Junction 8? These are the conventional perceptions of the young, vibrant town of Bishan – an ex-cemetery transformed into a heartland showpiece.

Our team, however, felt that there just had to be more to this rising area. Whether we were lifelong residents of the district or saw it as a mere part of our daily commute to school, we became increasingly curious about how this place came to be. Why was there even a cemetery in Bishan in the first place? Did people live in Bishan before the HDB flats were built? What was Bishan’s place in the Singapore Story?

Driven by overwhelming curiosity, we, in conjunction with the Raffles Archives and Museum, embarked upon the Becoming Bishan Project, hoping that the outcomes of our research would be able to provide a poignant contribution to our country’s jubilee celebrations.

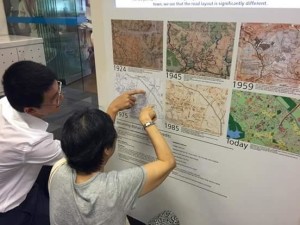

Our first step was to analyse the development of Bishan through maps. One of our members, Yilun, is an avid map enthusiast with an especial interest in urban redevelopment. With gusto, he surfaced many old maps of the area, the oldest dating back to 1924. Through painstaking effort, he managed to highlight the stark changes in the landscape of the area, as well as match old landmarks of the area to more familiar present-day ones. The topographical studies revealed many details about the geography of the Bishan area. Today, the land that makes up Bishan is rather flat. However, the contours of old maps suggest that pre-redevelopment,

Bishan was covered by rolling hills. Many photographs also show the grave-covered hills with the HDB flats of Toa Payoh in the background. This explains the how the name “Bishan” (“Jade Hills” in Mandarin) came about. One of our interviewees even compared the view from a Toa Payoh flat to a green dragon, because of the undulating hills and the scale-like tombs on them.

The highlight is a series of maps of Bishan tracing the landscape of changes from 1924 to the present (Photo RI Student Project Team)

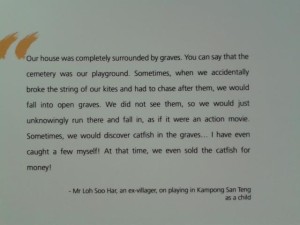

There were several kampongs within the cemetery, the most notable one being Kampong San Teng, whose kampong association members still meet regularly today. Interviews with the old residents revealed a rather self-sufficient community, with a school, farms, a teahouse and a market. There was also a cinema, Nam Kok cinema, in the Bishan area that screened Chinese and Western films. A worker in the KPT coffee shop in Bishan North told us of how he used to work there, proudly showing us his old posters of Elvis Presley and actors from Hong Kong. But when we asked about people’s impressions of Bishan before redevelopment, the greatest fears were not ghosts and spirits, but secret society activity.

We also made several exciting discoveries along our research journey. One was that Bishan was once a World War II battlesite! Jon Cooper, who also runs the Bukit Brown battlefield tours, managed to surface the battalion diaries and hand-drawn maps of the Second Cambridgeshire Regiment. These documented the action at Braddell Road in the dying days of the Battle for Singapore (1942). Further research revealed that the battle positions occupied by the British troops are the present-day locations of Junction 8 shopping mall, Bishan Library and Raffles Institution. This story was corroborated by many residents, who recalled the sounds of gunfire through the rolling hills of Bishan. Another revelation we made was that the philanthropist Wong Ah Fook was once buried in the Peck San Theng cemetery and his ashes now lie in the columbarium, something that even those running the columbarium had been unaware of.

Along the way, our team has also met and befriended many diverse characters, who each have their own personal stake in Bishan. From the intriguing Mr. Molay, a Cantonese-speaking Indian man whose father once owned a hundred cows in Bishan, to the unabashed Mr. Loh, who once ate human flesh to survive the deprivation of the Japanese Occupation, it is the stories of these people who make the Bishan Story come alive. We thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to talk to these individuals and learn more about the almost-foreign land that is the past. Later, we also spoke to current residents who told us about their thoughts and memories about this place. Though it is hard to say that the HDB dwellers of today have the same community spirit as kampong residents did, it was interesting to note how people develop, or fail to develop, attachments to Bishan.

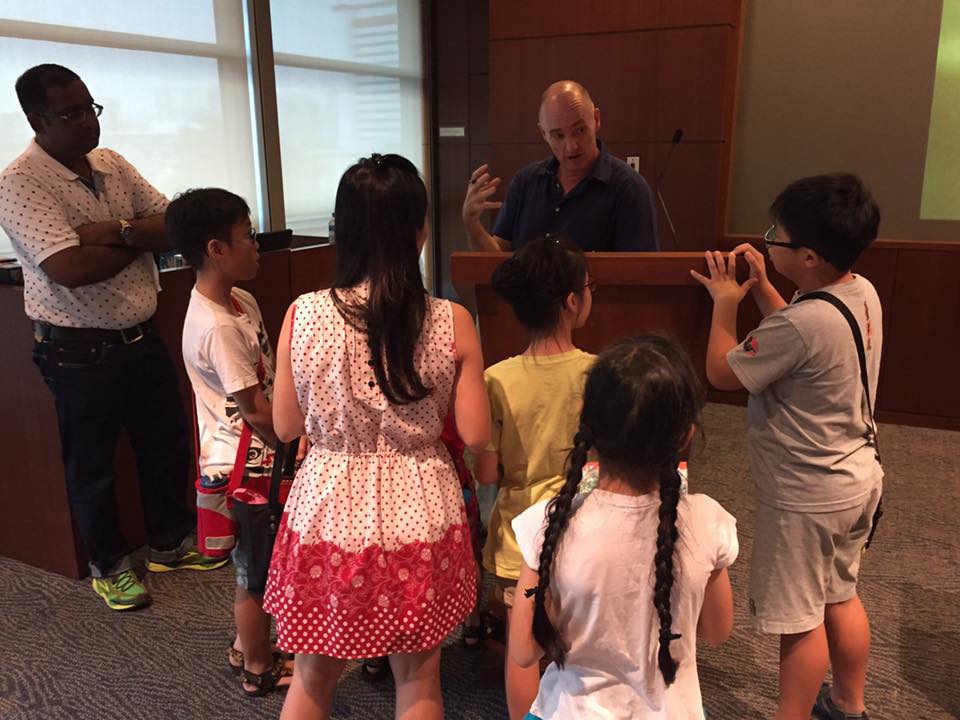

Visitors to the exhibition have a chance to listen in on their memories of Bishan as a cemetery and its social community life then (photo RI Project Team)n

We feel immensely privileged to have had the experience of exploring Bishan’s story and curating this exhibition, and hope that you might find meaning of your own in our fruits of labour and love.

The Becoming Bishan exhibition will be officially launched on 11 July (Saturday), from 9 am – 12 noon, at the Bishan Community Library. This event will be graced by Senior Minister of State Josephine Teo. The exhibition will run at the Bishan Community Library from 1 July to 23 August, Ang Mo Kio Public Library from 24 August to 30 September and Toa Payoh Public Library from 1 to 31 October.

This is a student project from Raffles Institution, as part of the South cluster schools’ contribution to the SG50 celebration efforts.

This blog post is a team contribution from the students of Raffles Institution involved in Becoming Bishan.

atBB reviews:

atBB visited the exhibition and we are struck by the sheer breath of the history and heritage the students have been able to uncover of Bishan and how it has evolved into what it is today. From the old to the modern, the curated posters capture more than a snap shot, but with carefully chosen quotes, it has emotional resonance such that, one can be transported to a different time and space in Singapore.

Of particular interest was the coverage on how the community coped with WW 2 and provided refuge for other residents in other areas in war torn Singapore.

The exhibits on WW II was an eye opener with artefacts from both Japanese and British sides.

Augmented with video recordings of residents interviewed makes this exhibition a exemplar template for exhibitions on other neighbourhoods to emulate. Accompanying the exhibition is a pictorial booklet which value adds the exhibition and makes for a treasured keep sake for those interested in history and heritage and the transition to the modern.

atBB has been following the development of this project since the students first approached us for help in understanding cemetery culture and symbolism. We are proud to have made a small contribution to this project and have to say that full credit go to the students for taking it so far from when they first began. Congratulations and well done!

Mdm Chng of the Pang Family – A Mother of Journalists, Educationists and Revolutionaries

by Ang Yik Han

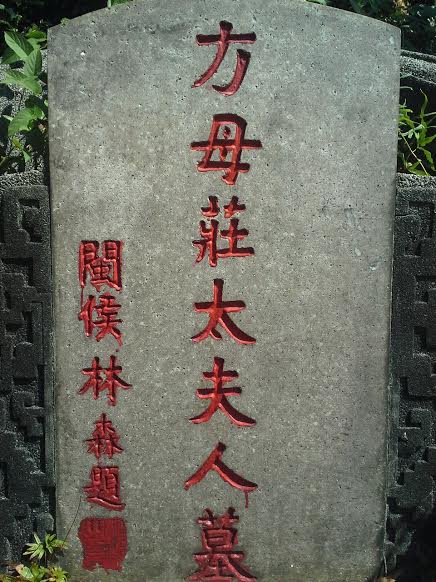

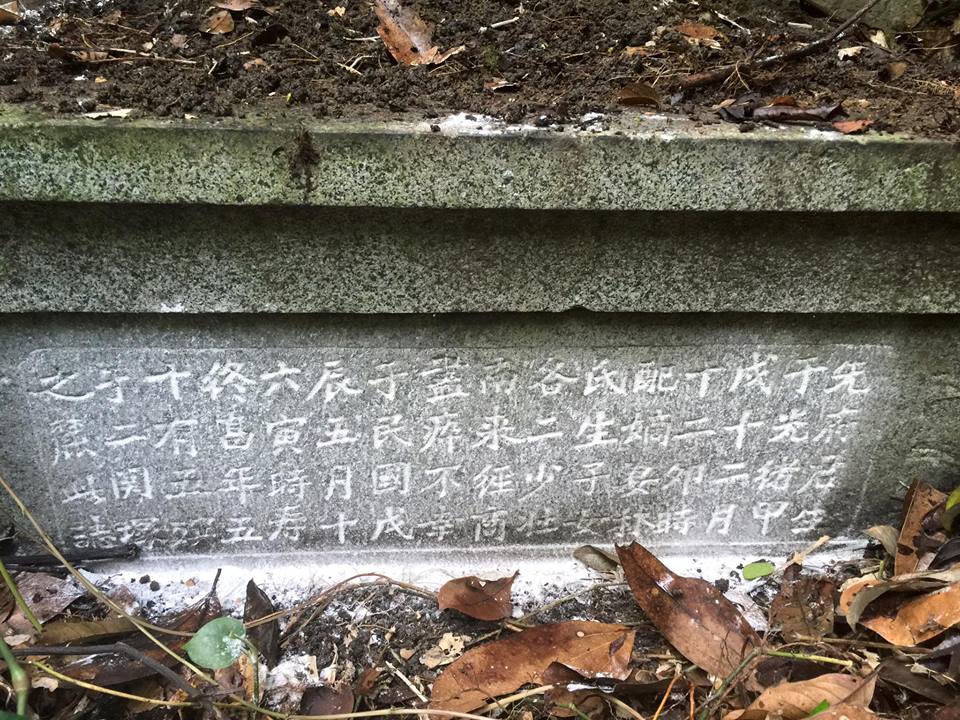

The tombstone of Mdm Chng, who died in 1936 at the age of 77. The characters on the tombstone were written by Lin Sen, KMT Chairman. (photo Yik Han)

Located at Hill 4 in Bukit Brown, the Teochew style tomb of Mdm Chng of the Pang family (方母莊太夫人) is simple and nondescript. A sharp-eyed observer will notice however that the calligraphy on the tombstone came from the hand of Lin Sen (林森), Chairman, of the ruling pre war Nationalist government in China.

Another sign of her family’s close connection to the Kuomintang was the fact in her obituary in the Nanyang Siang Pau, she was described as the mother of a martyr. This was in reference to her second son, Pang Nam Gang (方南岡), whose story was recorded in Feng Ziyou’s “Anecdotal History of the Revolution《革命逸史》” published in 1948.

Although two of Mdm Chng’s sons passed away before her, the names of all her sons were inscribed on her grave: Siao Cheok少石 (deceased), Nam Gang 南岡 (matyred), Chee Dong 之 棟, Huai Nam 懷南, Chee Cheng 之楨. Also present were the names of two daughters, though her obituary only mentioned one surviving daughter.

Pang Nam Gang had a good grounding in classical Chinese education. However, he spurned the traditional path of becoming a mandarin and chose to pursue his studies in Japan. There, he joined the Tongmenghui. Deeply committed to overthrowing Manchu rule, he devoted his time outside of studies to learning how to make bombs.

In 1905, Pang and eleven of his compatriots in Japan were ordered by Sun Yat-Sen to return to China to assist in the Huang Gang uprising in the Teochew region. Injured while preparing bombs, he was brought to Hong Kong and hospitalised, hence missed out on the action. When the uprising petered out, Pang decided to join his uncle who was a local governor in Gansu, with the intention of seeking opportunities to incite the local Hui people to rise against the Qing. His uncle was initially pleased to see his nephew, but flew into a rage when word reached him that Pang was a revolutionary. Locked up by his uncle, Pang escaped with the help of other relatives, stealing two horses and riding to Hankou, where he sold the horses and boarded ship for Japan to continue his studies. Eventually, he made his way to Penang where he became the editor of the Kwang Wah Yit Poh newspaper which was linked to the Tongmenghui.

The young revolutionary could not sit still for long. When news of the successful 1911 uprising in Wuhan reached the Nanyang, Pang rushed back to China where he raised a fighting force in his home county of Pho Leng. When Yuan Shikai was elected the first President of the nascent Chinese Republic, Pang felt that Yuan could not be trusted as he had too many links with the old regime. Disgruntled, he returned to Penang where he took up his old job at the newspaper.

Pang’s worst fears came true in 1915 when Yuan Shikai assumed the title of Emperor. This time, he could no longer abide the situation and returned to China again to fan the flames of revolution. Unfortunately, he was captured in Macau by Yuan Shikai’s agents and smuggled across the border and imprisoned. At first, he assumed a false identity and did not divulge any information even under torture. However, his fervent preaching of revolutionary ideas to his fellow prisoners gave him away and he was summarily executed. So perished a martyr of the Chinese Revolution at the age of 29.

Photo of Pang Nam Gang (reproduced from the book “The Teochews in Penang: A Concise History” by Mr Tan Kim Hong)

The house of Pang Nam Gang in Pho Leng (taken from the site 方益森的博客 http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_756c1ab90101ipv2.html)

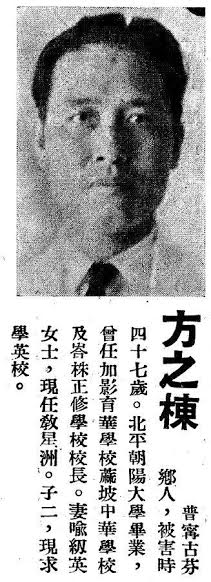

Mdm Chng’s obituary also mentioned that her three surviving sons were active in the areas of journalism, education and social works. Her youngest son, Pang Chee Cheng (方之楨), was in the limelight as well for his involvement in politics. A journalist, he was a KMT cadre who actively canvassed support for the party as one of the main committee members of the Nanyang branch headquarters.

In 1930, Sir Cecil Clementi became the Governor of the Straits Settlements. He had a dislike of the KMT due to its instigations of strikes during his previous posting in Hong Kong. On the day that he arrived and assumed office in Singapore, it was unfortunate that the KMT Nanyang branch headquarters chose to hold its general meeting at the same time.

One of the first acts of the Governor was to summon the KMT representatives to his office where he told them in no uncertain terms that the KMT was not allowed to operate local branches in the Straits Settlements and Malaya. A few months later, the Governor upped the ante by issuing orders to deport Pang Chee Cheng and another KMT stalwart; well aware of the situation, they left on their own for China first.

Quiet diplomacy between the British and Chinese governments behind the scenes eventually led to the deportation orders being rescinded. In later years, Pang Chee Cheng was based largely in China where he was active in the Overseas Community Affairs Council (僑務委員會) set up by the Nationalist government.

Pang Chee Cheng often met with renowned personalities of the day. So it was that when the Indian poet Tagore visited in 1927, Chee Cheng arranged for him to travel to Muar and visit Zhonghua School (中華學校, a forerunner to today’s 中化), where Tagore was received by his brother Pang Chee Dong (方之棟) who was the principal then. A graduate of a university in Beijing, Chee Dong was successively principals of Chinese medium schools in Kajang, Muar and Batu Pahat. In 1933, he may have worked as editor of a Chinese newspaper in Rangoon as well.

After the Japanese invaded, he perished during Sook Ching in Singapore, leaving behind his widow and 2 sons.

A short biography of Pang Chee Dong in the 8th anniversary commemorative publication of the Nanyang Pho Leng Hui Kuan published in 1948.

The fourth son Pang Huai Nam (方懷南) was the first editor of Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商報) established by Tan Kah Kee in 1923. Slightly less than a month into its publication, he left the newspaper as the Straits Settlements authorities found his writing too political for their liking. He was also a committee member of the Poit Ip Huay Kuan and principal of Choon Guan School. It was mentioned in Phua Chay Leong’s “The Teochews in Malaya” that he shared the same sad fate as his elder brother Chee Dong during Sook Ching.

Mentioned as well in Mdm Chng’s obituary was one of her grandsons, Pang Say Hua (方思法). Born in Singapore to her eldest son, he was “fostered” to his uncle Pang Nam Gang; his father was convinced that his second brother would come to no good end with his revolutionary ways and hence it was better that he had a son to his name. Pang Say Hua went back to China to study and subsequently became a signaler in the Nationalist Army. He was one of the many caught up in the tumult of the times. Due to his background, he suffered after the Communists took over, being imprisoned for over ten years. After his release, he worked at various jobs and retired in 1980. His story became known when a civic organisation in the Teochew region which sought to recognize veterans of the Sino-Japanese War found him and publicised his story.

Single for life, he attended church regularly and spent his last days in a Christian old folks’ home where his favourite pastime was to watch Teochew opera. He died in Jan 2015, a month after he celebrated his 104th birthday.

Source: http://www.stcd.com.cn/html/2013-09/21/content_464908.htm

Recent Comments