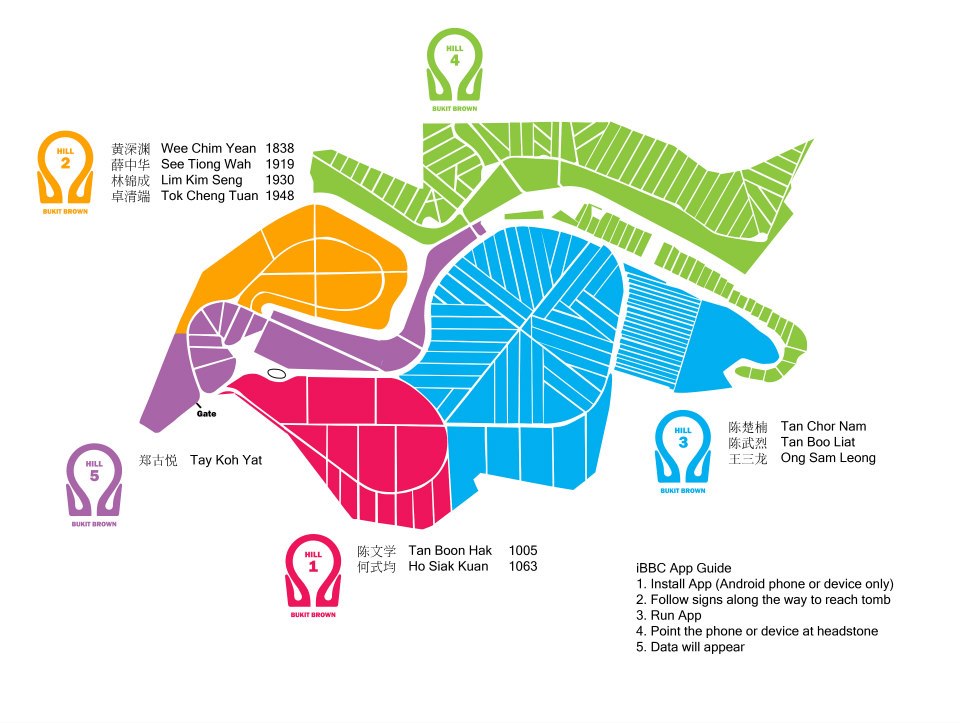

The iBBC App Guide is a FREE App to accompany you when you visit Bukit Brown Chinese Cemetery. It has been developed by the The Bukit Brown Cemetery Documentation Project led Dr Hui Yew Foong. Brownie Khoo Ee Hoon designed the artwork of the map. There will be physical markers on site to guide the way.

Download your App from the Google Android store now, here

Check out a video demo on how it works here

And once you have downloaded you can test the application here before heading to Bukit Brown!

Note: This is a sample of a few tombs. The the App itself has data of over 20 tombs introducing you to the pioneers buried there.

Those with accompanying numbers e.g. Tok Cheng Tuan 1948 are staked and and will be exhumed. to make way for the eight lane highway. You only have a few months left before you can catch this tomb in all its magnificent glory.

The Wayang in the Tombs

by Ang Yik Han

(Popular tales performed in Chinese Wayang carved in iconic scenes on tomb panels.)

In the ” Romance of the Three Kingdoms” General Guan Yu is immortalised as the epitome of loyalty and righteousness. He played a significant role in the establishment of the state of Shu Han during the period of the Three Kingdoms.

Guan Yu took a poisoned arrow in his right arm when he was besieging the city of Fanzheng. Determined not to retreat, he called upon the services of the famed physician Hua Tuo to treat him on the battlefield. Hua Tuo saw that the poison had spread to Guan Yu’s bones and he had to operate on his arm and cleanse the poison by scrapping his bones. Undeterred, Guan Yu subjected himself to the ordeal, all the while sipping his wine and playing a game of chess. ( photo by Yik Han)

Legend? Embroidered truth? It does not matter, over the ages from at least the Ming Dynasty, the image of Guan Yu smiling and sipping his wine while Hua Tuo scrapped his arm bone has been a source of wonder and encouragement for many.

This tomb is located in Hill 2 and belongs to the Teo Family.

More tombs featuring Guan Yu, here

From Madam White Snake :

A panel possibly of the White Snake parting with her husband after he was taken in by the words of the monk Fa Hai. (photo Yik Han)

The White Snake and her companion the Green Snake (the two ladies in the boat) leading the creatures of the sea in an attempt to flood Jinshan Temple and rescue her husband Xu Xian (许宣) from the clutches of the monk Fa Hai (法海). (photo by Yik Han)

From Nezha conquers the Dragon King :

Nezha storming the palace of the Dragon King with his signature Qiankun ring in one hand, his spear in the other and riding on his “fire wind wheels”. The Dragon King flanked by his courtiers are seated on his throne on the right, a bumbling turtle is trying to resist Nezha, and on the left is a shellfish nymph. (photo Yik Han)

Nezha storming the Dragon King’s domain as the Dragon King riding on a magnificent dragon beats a hasty retreat covered by his underlings. The armed figure on the right may be Nezha’s father Li Jing (李靖), furious with the havoc created by his son (Photo Yik Han)

The panels can be seen at the tombs of Poh Cheng Tee and his wife, and mother, in Hill 1, stake numbers 1017 – 1019. Exhumation of staked tombs in the way of the 8 lane highway is expected to begin after April 15th

饮水思源 Remember The Source of the Water

Elizabeth Ong and Emma Lim

By Catherine Lim

In 2002 in London and Scotland, two Singapore couples stationed in the United Kingdom, welcomed new arrivals, both girls. Born four months apart, the Ongs in London named their daughter Elizabeth and she was their second child. The Lims in Scotland named their daughter, Emma and she was their first born

In 2006, after 13 years abroad, the Ongs returned home to Singapore because they felt it was time for their young family to root themselves to their country and they returned to the family home which with their children now houses 4 generations. Their children, elder brother Alexander to Elizabeth were enrolled in Nanyang Primary School and because they were still very young adapted well.

In 2010, the Lims after 12 years abroad returned home for very much the same reasons, to be with family and reconnect to their homeland. By then Emma had a brother and a sister. Their grandparents had visited them frequently when they were in Scotland and the grandchildren settled down comfortably in Singapore, all under one roof. Emma was able to enroll in Nanyang Primary School.

In 2011 Elizabeth and Emma met for the first time. They barely spoke in the first term of school but by term two their friendship just took off. Both are in the choir; Emma sings alto, and Elizabeth second soprano. Their passions are artistic. Dance lessons for Emma every weekend, and Elizabeth has been talking art lessons since 2007. Their mothers met and play dates were arranged whenever the girls had free moments in their busy schedules of school and extra curricula activities. But mostly the girls just text each other when apart.

As their friendship grew so did their mothers’. It was not long before they realised they had similar experiences of living abroad and coming home. When their husbands came into the picture, the Ong and Lim families found a deeper connection which reached back into Singapore’s past and found another friendship which their daughters’ echoed.

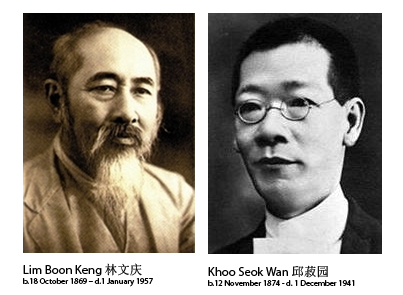

Elizabeth, is the great great granddaughter of Singapore pioneer and scholar Khoo Seok Wan and Emma is the great great great granddaughter of another luminous pioneer, Lim Boon Keng.

Lim Boon Keng and Khoo Seok Wan

By Ang Yik Han

One was the dapper son of a rich rice merchant from China, a poet and scholar who sat for the Imperial exams. The other was a local born Western trained doctor, recognised by government and society as one of the leading voices of the Straits Chinese community. Khoo Seok Wan and Lim Boon Keng made an unlikely pair of friends. But the historical and political milieu of their times gave birth to unlikely pairings.

Both men were supporters of the reformist movement in China which sought to re-vitalise the Qing Dynasty. Khoo founded the Thien Nan Shin Bao, a local Chinese newspaper sympathetic to the reformist cause; Lim Boon Keng was its English editor. Subsequently, Lim and his father-in-law took over another Chinese newspaper which also adopted the reformist line.

When Kang Youwei, the leader of the reformists, fled China after the Reform’s failure, Khoo offered him shelter in Singapore and sucour for the cause. With the threat of assassins dispatched by the Qing government hanging over Kang, Lim worked with Khoo and the Straits Settlements authorities to protect him. Kang moved three times during his short stay of five months in Singapore. The first two places were properties belonging to Khoo Seok Wan and the third hideout was none other than Lim Boon Keng’s house.

The two also combined their efforts in education and social reform. They established the Singapore Chinese Girls School with other progressive members of the Chinese community at a time when the proper place of women was at home and female education was look upon with disdain. Half of the funds for the school ($3000) were contributed by Khoo Seok Wan and both men served on the inaugural Board of the school.

Khoo’s role in society was greatly diminished in the years following his bankruptcy. He became destitute and had to scrap a living with his pen. Even then, the friendship continued.

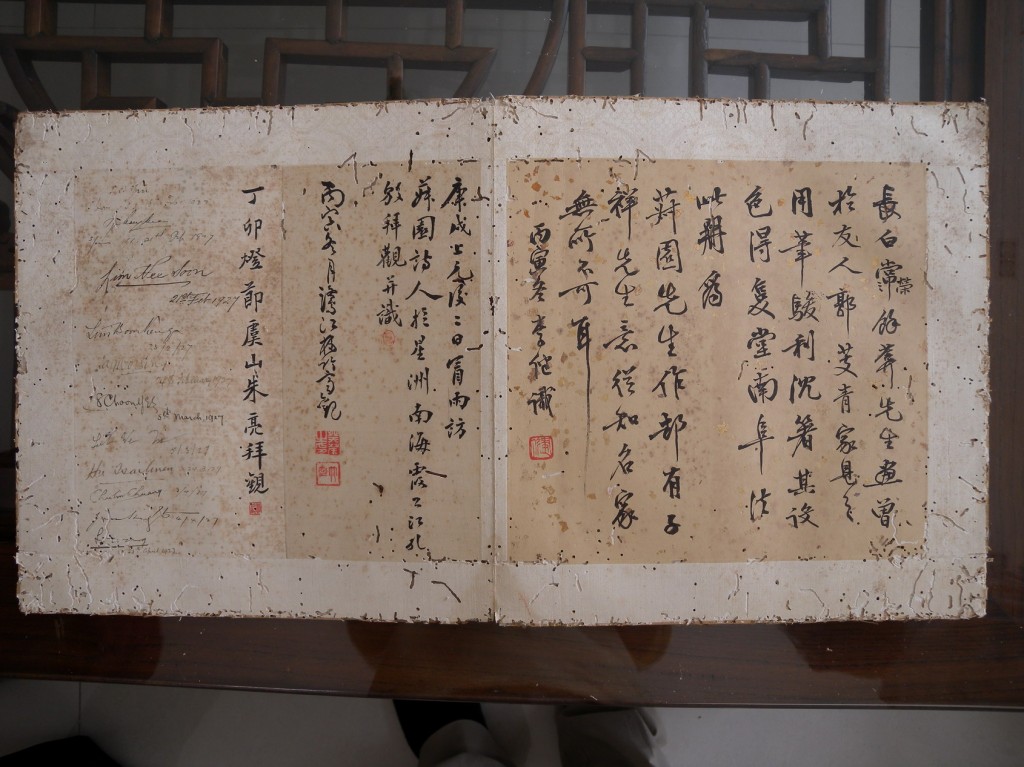

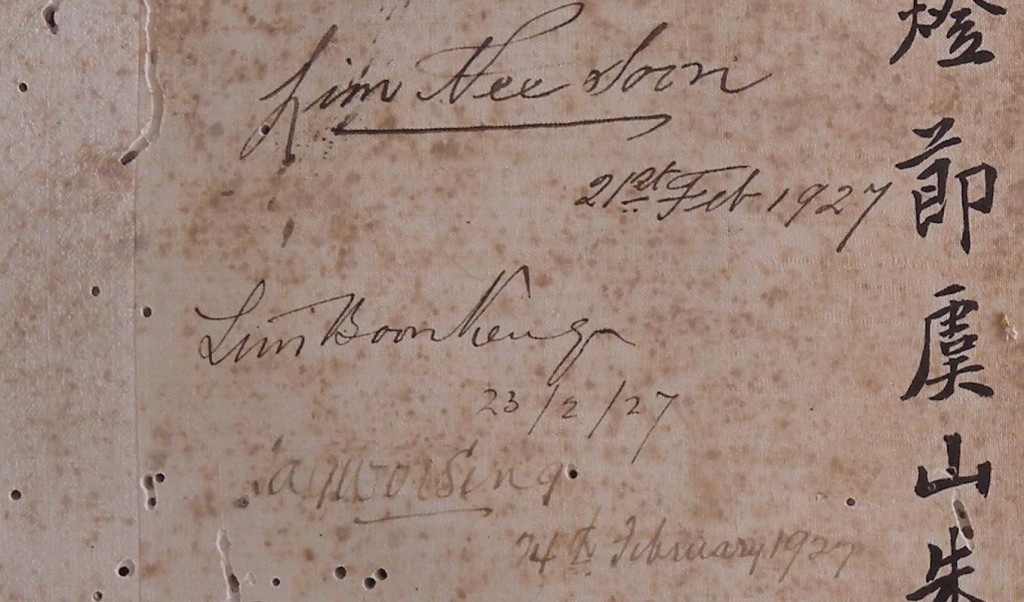

The Ong family has in their possession a book of calligraphy and original paintings which belonged to Khoo Seok Wan.

This book bears the signatures of various guests who had the honour of leafing through it, including Lim Boon Keng who visited in February 1927. By then, his full time job was the Chancellor of the Amoy University. Lim’s occasional trips back to Singapore were primarily for the never ending task of raising funds for the University, yet somehow he found time to visit his old friend. This signature is testimony to their enduring friendship.

Post script on Emma and Elizabeth

Emma on her friend, Elizabeth:

Elizabeth is pretty and cute.

Elizabeth is smart, funny and my BFF.

Elizabeth has a kind heart and always helps me when I am in need.

Elizabeth on her friend, Emma:

Emma is my BFF and she is fun and exciting to be with.

She always sticks by me through thick and thin.

Emma is pretty and she is a true friend to me.

by Andrew Tan

In Bukit Brown Cemetery, an avenue, like prime real estate, connects Singapore’s prominent families—all inter-related, as these powerful cliques were linked by arranged marriages to perpetuate their wealth and influence through six generations, during 150 years of British rule (1819 to 1959).

Chronology

1819-1867 Beginnings

The earliest Asian elites in Singapore were comprador-kapitans from Malacca, who brokered with European (mainly British) companies, exclusive credit and arms deals. To procure native products for Europeans, compradors resourced from powerful clan headmen who controlled the supply of coolie labour, ships, and native products—crucial to entrepot success. Business partnerships were tied by arranged marriages between all families.

Family examples: Tan Tock Seng and his family network supplied and distributed manufactures for the British “country traders”; they also married influential relatives of the compradors and Kapitan Cina. Together, this was the first powerful clique in Singapore, which broadened (after Singapore’s cessation as entrepot of the opium-arms trade following British victory over Qing China) to include revenue farmers and labour contractors as their enterprises penetrated Southeast Asia.

1867-1900 Rise

From 1867, with Singapore a crown colony, the long established families recruited scholars and professionals as sons-in-law, to perpetuate their vested interests (e.g. tax-free “free trade” policies, opium farms, colonial intervention in tin-rich Malaya) through positions in the advisory board and councils at the municipal, rural and legislative level; appointments rotated among relatives (who advised the Governor on nominations) to ensure advantageous policy continuity.

The immediate decades after Suez Canal opened in 1869 diverted oceanic traffic through Singapore. To compete internationally, merchant families pooled their resources into joint-venture consortiums (in steamships); their offspring intermarried too. Ties between in-laws counted more than paper contracts.

Family examples: Notable Queen scholars (Lim Boon Keng, Song Ong Siang etc) and other top professionals were sons-in-law of well established merchant-shipping families like the Wee-Ho Hong-Lee group, as well as others who partnered in Straits Steamship.

1900-1941 Peak

Insatiable demand for World War One commodities (tin, rubber) produced the first multi-millionaires in Singapore: these nouveaux-riches—their heirs and heiresses were courted and charmed by Old Money. Merging New Money with Old gave birth to multifamily-owned conglomerates (e.g. OCBC, UOB, Straits Steamship) tying together banks, ships, plantations, factories and newspapers.

Large fortunes would aggrandize social ambition: Plutocrats usurped collective and consular institutions (e.g. Ngee Ann Kongsi, Chinese Chambers of Commerce), to connect with powerful Chinese warlords of lucrative market potential, offering to regimes funds for schools and humanitarian relief, using family-controlled newspaper editorials to galvanize mass involvement.

Ability to lead the Chinese masses into action was recognized by the British military; however, these plutocrats on war councils were relocated with their families to India just weeks before the Japanese Occupation.

Family examples: Families from shipping, commodities, revenue farming, and remittances, co-founded the conglomerates of OCBC and UOB, with ties to the burgeoning sectors like film and publishing, and family connections in politics.

1945-1959 Turning Point

In postwar Singapore, enriched by military contracts in the Cold War, scions used their wealth to contest for elected self-government, but the expanded, impoverished electorate rejected these “rich men’s parties” (Progressive Party and Democratic Party, whose members were related, merged into the Liberal Socialist Party), in favour of a new regime, the People’s Action Party (PAP).

Family examples: Contracts were monopolized by consortiums who subcontracted to each other. Chain of suppliers for the British military coalesced and expanded to retail giants.

1959 onwards Decline

Following Singapore’s independence under the PAP, the old elites diminished in economic influence: their once-predominant, century-old monopoly of colonial contracts was overshadowed by the growth of public state-sector industries in partnership with foreign multinationals. Attrition too, their vast landholdings compulsorily acquired by the state for redevelopment.

Their hereditary clan-leadership in communities has been subsumed by government departments that fund and run all neighbourhood activities and amenities. More than cultural and community centres, clans were once the centre of powerful labour unions. They once ran schools; but today, the Education Ministry syllabus and compulsory mandarin has created a generation disconnected with their dialect heritage, previously stressed in clan schools.

Arranged marriages and pedigrees became obsolete as post-war mass education broadened careers and widened choices in life partners. Also, professionalization broke down class barriers. The Women’s Charter in 1961 ended the quasi-feudal family structure.

As Singapore developed to become a middle class society, a new breed of technocrats allied with the PAP replaced the Old Establishment.

A multifamily tree, with 1000 people from 100 families, 6 generations interlinked in strategic alliances from the late 1700s to now, will be published in 2012. I shed light on the influential cliques (made up of powerful families) who dominated Singapore’s society and economy past two hundred years. Andrew Tan

Theatre practitioner, Alvin Tan visits Bukit Brown for the first time and shares his impressions and reflections on where he sees its place in the Singapore story – past, present and future

It began with a text message:

Jasmine alerts me to a Bukit Brown walk (Saturday 14 April 2012) on SMS:

Hi all,

Any one up for a stroll through Bukit Brown this Saturday morning 14th APRIL from 9am to 11-ish? The good volunteer peeps of the Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown facebook group have agreed to take us on a walking tour led by the tomb whisperer himself – the brilliant Raymond Goh. Pls sms me if you’re inTERESTED. Pls ask along friends family other filmmakers. Children and infants in baby carriers are always welcome! <<jasmine

I responded that I was interested but unable to confirm because it was a very busy week and I might be too exhausted. I’m not much of a morning person. I stalled. Jasmine persisted. And on Saturday morning, I was on the MRT meeting Jasmine at Tiong Bahru Station, jumping into a cab and we were on our way to Bukit Brown.

I was relieved that I reached Bukit Brown with such ease. Getting off the cab, friends from the theatre and film communities were already there. And soon we were to be inducted into the Bukit Brown community as we waited for for Raymond to arrive.

The tranquil environment was soothing; ordinary and extraordinary at the same time. Why is the dead impacting on us so much with this Bukit Brown saga? Why is heritage beginning to matter to us? Have we been losing too much of that in recent years and more Singaporeans are feeling the loss?

It’s happening at a point in Singapore’s history, after GE 2011, after the KTM/Green Corridor episode. It’s been bringing Singaporeans from all walks of life together – advocates, interest groups, NGOs and the public. I’ve never witness a cause being mainstreamed so fast here in Singapore that it is beginning to take on a momentum of a small movement.

Petitions have been started, position papers on both the heritage and habitat of Bukit Brown have been written, outreach activities to create awareness and appreciation of Bukit Brown to draw the Singaporeans and visitors from all walks of life, took flight. Whether it shows a sign of maturity, that Singaporeans are beginning to be stakeholders as citizens of this country is not as important to me as the fact that it’s the only kind of Awakening Singaporeans can afford. There is not just a small group of people, a core of activists who can be easily contained, labelled, character assassinated and dismissed.

The realisation that organic change is the best revolution for me accompanied me throughout the morning at Bukit Brown as I took in the stories shared so generously by the tomb whisperer, Raymond Goh. Just looking at all of us being attentive and learning about our history, cultural heritage made me appreciate the moment we were all in as we moved from one tombstone to the next.

Then the Peranakan tombs came into focus. It was not just the Chinese that were buried at Bukit Brown. There were so many Peranakans buried here as well. The tiles that lined some of the tombs made me wonder again how the Peranakans were determined to distinguish themselves from the other Chinese (sinkehs) who came later. The fact that the Peranakans integrated and assimilated successfully in Nanyang again arose in my mind, juxtaposed to our contemporary reality of new migrants arriving at our shores today. What would that outcome be like compared to the Peranakan story of our past? How rich these lessons are or can be and how did this visit to Bukit Brown inspire such multi-layered discourse in my mind? What can happen if history teachers, dramatists and other artists have site-specific happenings, engaging the public. Surely this would be something concrete that the Community Engagement Programme would gladly commission to build social cohesion meaningfully amongst Singaporeans.

Then of course a friend’s question bothered me: ” Why only now? Before the whole ruckus, who bothered about Bukit Brown? So why bother about it now? It can go, it wouldn’t bother me. It didn’t bother me before, and so, it shouldn’t bother me now. It’s a loss I can afford. “

Or can we? As we walked the trail, with nature all around us, I easily fell into deep reflection, sometimes conscious of the people around me and sometimes just amazed at how beautiful Singapore can be. Why do we make invisible what is astoundingly beautiful to replace it with something that comes from economic pragmatism? I can’t find it in myself to grief. Maybe because I am 49 and have been toughened over the years. There is never much use fighting for causes, fighting for what we believe in because we will come face to face with disappointment and disillusionment especially when it is already a done deal. Why should this time be any different?

But the above picture shows a group of people strolling downhill towards our next destination and those who were ahead loved the image so much that we all whipped out our cameras, almost simultaneously to capture the image.

Therein lies the hope: this small group of believers were walking down because they had walked up the tiny hill before this. This group of travelers believed enough to submit to the necessary demands of this route. There will always be people who will continue to persevere for what they believe in, shaping expectations along the way, building capacity, developing and strengthening community bonds. This is the birth and nurturing of stakeholders. No cynicism should discourage that impulse. It is not a group of people egging the public on. It is the public coming from all walks of life meeting at the cross road called Bukit Brown.

By the end of the walk, Bukit Brown had become a metaphor in my mind. But it will not become just a cerebral relic. Something in my heart was beating and burning. Something I have missed for some time – the quiet rhythm of a community forming, unbeknown to most of us. Something young and raw but definitely alive amongst the thousands of tombs all around us.

Editors note:

We have included additional photos from the tour including this “hat trick” of great spontaneity and generosity, instigated by Tan Pin Pin. $200 was collected to pay a tomb keeper to clear a couple of graves of undergrowth

About Alvin Tan and

From Catherine: I wrote this almost 5 years ago for The Straits Times. It seems to stand the test of time

Preservation and the soul of a nation

Catherine Lim Suat Hong, For The Straits Times, 17 July 2007

(c) 2007 Singapore Press Holdings Limited

MY FAMILY home, the National Stadium and an 80-year-old tree that was just felled over the weekend – in my mind they are all connected, and at three levels of engagement, from the personal, to the national and the global.

My family home at Serangoon Gardens was sold early this year.

In my memory it stood as a place of good times and bad. We moved in during the early sixties, and extensions were built, somewhat willy nilly to the original structure. We had one toilet and one bathroom shared among a family of six, a live-in maid and at various times even a tenant.

In the early nineties, my brother and his wife bought the house and rebuilt it. The new home had three bathrooms for a family of five.

I moved out with my parents to Bishan just before the turn of the millennium. I’m making new memories here and have no regrets for the family home no longer in our hands.

Not so simple though for the National Stadium. Watching the fire in the cauldron of the grand dame snuffed out for the last time on television recently, I was taken back by the groundswell of emotional response, including mine.

As a fledgling journalist I had covered National Day stories on the ground. In later years, it marked a high point in my career, when I helmed the live television commentary in the commentators’ booth, above the VIP seating area with an unparallel view of the parade.

I felt the earth move with the 21-gun salute; a hair’s breadth away from the men and their magnificent flying machines as they seemed to swoop towards me in the fly past; and as night fell the sky lit up in a kaleidoscope of colours that blew my mind away.

My personal memory counts for little. But viewed from the macro lens of a young nation, it is part of the collective memory of Singapore’s sporting history, of romances which blossomed on the stands and on track, and the passing of the baton from father to child.

Still, I was paradoxically ambivalent about this collective loss. After all, sporting history will continue to be made, love will still blossom and National Day Parades will continue to evoke patriotism in the continuum of time and space. Then I read Mr Ho Weng Hin’s compelling piece – Losing a slice of history – in these pages on Friday. He asked: ‘As another nation-building icon bites the dust… was it all really inevitable?’

He brought to the fore of the debate about conservation an international perspective in favour of rejuvenation through technology, even as our technocrats invoke the tide of progress as the cornerstone of their arguments for demolition.

Time and tide waits for no man. But time can be suspended, to allow generations to be bridged in a past that lives on into the present and beyond.

Much has already been lost. How much is subjective, not objective, and history will be the judge. But when the physical proof of such memories is demolished, all we have left will be words and pictures in libraries and museums, the purview of scholars many years down the road.

And it is to Braddell Road I now turn – to the 80-year-old angsana tree right smack in the middle which is now no more; the cut was swift just days after it was announced that it had to go because it posed a danger to motorists.

The decision came, ironically, hot on the heels of the Live Earth concerts to galvanise awareness of a planet in crisis. It prompted letters to the newspapers and on the Internet. Tree lover Sim Hong Gee wrote: ‘What is more appalling is the rationale for removing the tree – because motorists were not observing the speed limit of 40 kmh posted on that stretch of road. With all the well-posted road signs, it is clear to users… that one has to slow down significantly, given the extent of the road curvature even without the tree being in the middle of the road.’

The other letter that was published came from a neighbourhood committee member who wrote: ‘I have never been able to understand the unyielding stance taken against the cutting down of trees (by the two authorities Land Transport Authority and National Parks Board) even when there is a danger of them causing injury and death.’

He added: ‘I have always thought it ridiculous to spend $200,000 to have a major road split up just to avoid cutting down a tree.’

Judging by the netizen response to these two opposing letters, the latter were drowned out by supporters of the tree. But to no avail.

Human life is primary and rotting trees which pose a danger to innocent pedestrians and drivers should be felled. But not this tree. It was healthy, just inconvenient to speedsters. As one netizen pointed out, you don’t obliterate drink driving by eradicating alcohol; you educate.

The nexus of conflict, between saving the environment – both natural and man-built – and material progress, will continue to dog us.

We can establish a principle: that when we have toted up the pros and cons of demolition as compared to that of preservation – and by preservation I mean a living and breathing preservation – we subject the balance to the scrutiny of the collective consciousness. And return to the drawing board to relook, rethink and resketch new possibilities.

Our government has pledged that it is here for the long haul. As it contemplates how to root Singaporeans to the country, economic success alone is not enough; equal weightage has to be given to the soul of a nation.

There is still time. We are a city of possibilities.

The search for a long lost aunt buried at Bukit Brown began last year, when Miho Tan requested the help of Raymond and Charles Goh to locate his father’s sister. She provided these details

Name : Tan Lay Chee

Grave : C III, 857

Age : 18

Year of death : December 1932

Following up this year, Raymond found Miho’s aunt and from her tomb inscription discerned that Tan Lay Chee died at the young age of 17 on Christmas Day, 1932. She was unmarried, but a boy was inscribed in the tomb as a “stepson”. According to the information Raymond gathered – the burial registry does record cause of death – she died of mo tan, a kind of high fever.

He recalls her family visiting her tomb a few years ago but they had forgotten the route as the surrounds had become quite inaccessible due to fallen trees and overgrowth.

The family of Tan Lay Chee visited her soon after Raymond located her tomb, and brother Lay Chee connected once more with his elder sister.

Also buried at Bukit Brown, is Miho’s grandfather. Miho captured a family visit to his tomb in February in a video here

Grandfather Tan Choon Kiat was a book keeper and died at the relatively young age of 51 years old.

Miho’s grandmother, Lim Geok Yan survived her husband by more than 30 years. She died just past her 80th birthday and her ashes are interred at Bright Hill Temple at Sin Ming. Her grandfather’s tomb, is a double tomb but he rests alone. It can be deduced that his wife was originally intended to rest side by side with him.

The life and times of Lim Geok Yan is deeply etched in the mind of Miho’s father. He was the youngest of 8 children, 6 boys and 2 girls. We know she had to bury a child and as a young widow life must have been tough. Miho recalls what his father shared with him:

“Being a tough nonya my Dad says she had to pawn her jewellery bit by bit in order to maintain the household , the daily expense had to cover (they lived in a traditional Peranankan house), around 16 members which included 7 “cha bor kan” – Hokkien for maids. She was a strict mother too (Dad did not elaborate). I’m sure she would have been been a strict grandmother too and maybe I’ll be allowed to wear traditional Baba wear on special days.”

Miho remembers being taken to the Baba House, where her father pointed to a portrait of Lim Ho Puan hanging there, and he said to Miho, “there, that is your chor kong – (Hokkien for great grandfather)”

Lim Ho Puan is among a list of luminaries which include Lim Boon Keng, Lim Nee Soon and Lim Yew Hock named in the book Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, Business, Politics and Socio Economic Change, 1945 – 1967

A simple tomb of a long lost aunt, has become for the niece who never knew her, a touch stone revealing a family history which is both personal and historical.

几枚白石伴青珉,

小筑坟莹隔岁春

地下有灵相谅解,

迟工原是为家贫.

A few pieces of white rock accompany the green stone,

A little grave built but alas late one year

My dear I hope you can understand the reason,

I am late to build because of my poverty.

(Khoo Seok Wan (1874-1941) in memory of his wife, Lu Jie (陆结)

He was a Confucian scholar, a political activist in revolutionary China, a prominent community leader in Singapore and an early advocate for education for girls who helped set up the Singapore Chinese Girls School.

Born into a wealthy merchant family, Khoo’s fortunes waxed and waned because of his extravagant life style ( he was known to be a generous host) and the over extension of his funding activities to revolutionary causes. But embedded in his life is a love story which captured the heart of Bukit Brown resident tomb whisperer Raymond Goh; he was determined to find his grave.

When Khoo Seok Wan’s wife died in 1936 at the age of 44, his fortunes were on the wane and he was bankrupted. He could not afford a tombstone for his wife whom he buried in Bukit Brown. So he buried his own tooth with her and when he could afford it the next year also constructed his own tombstone in preparation to be reunited her one day. The poem was penned to mark the occasion.

Khoo was born in Fujian, China, and followed his mother to Macau before he joined his father in Singapore in 1881. His father, Khoo Cheng Tiong (邱正忠), was a successful rice merchant and prominent community leader in Singapore. Khoo was schooled in traditional Confucian education, and when he was 15 years old, he went back to his hometown to prepare for the Chinese imperial examinations. He passed the district and provincial examinations to attain the level of a juren (举人) that qualified him as a candidate for the central government imperial examinations in Beijing, but he failed in that attempt in 1895 and returned to Singapore.

Khoo suffered from leprosy and lived his last years on the generosity of his friends. He died in Singapore at the age of 68 on 1 December 1941.

He was buried in Bukit Brown cemetery beside his wife. Earlier this year, Raymond Goh finally tracked down the tombstone Khoo built for himself and his wife from records in the Burial Register lodged with the National Archives. Khoo Seok Wan’s tomb is in Blk 4 Section C, is in the path of new dual 4 lane road.

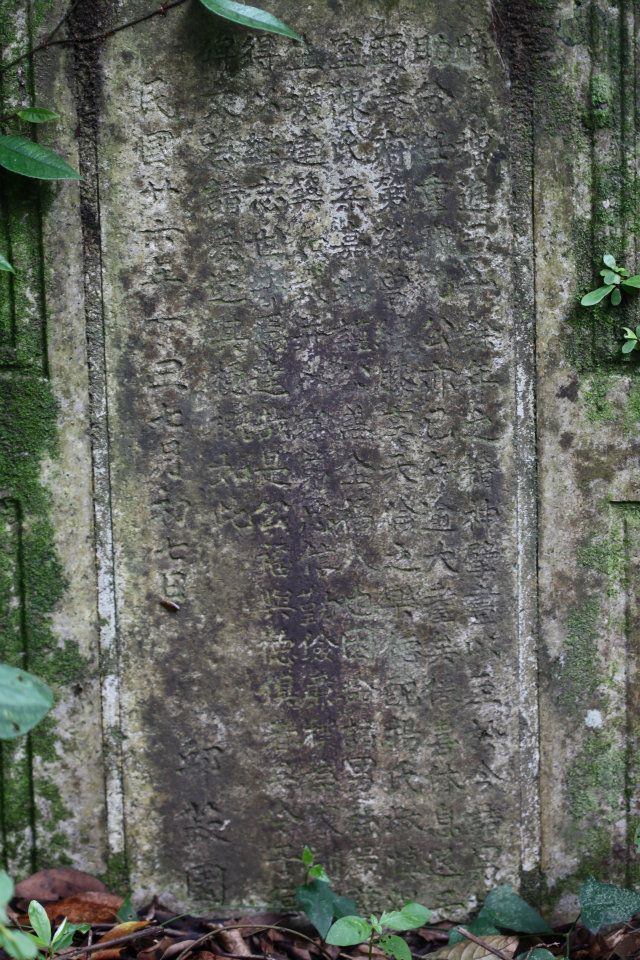

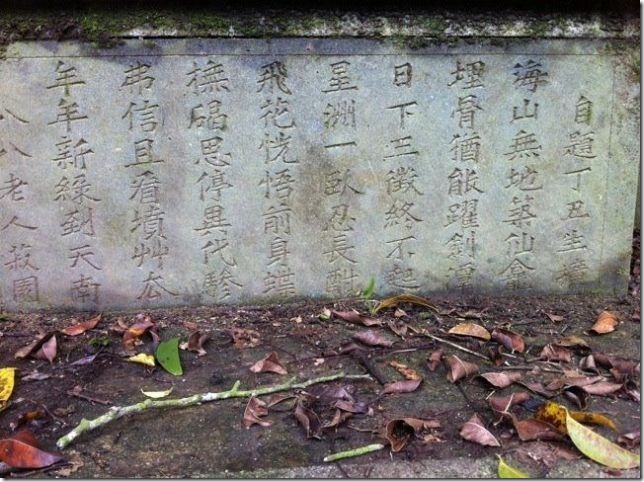

Khoo Seok Wan “live” tomb, inscribed on the altar is his epithet which he penned himself (photo:Raymond Goh)

海山無地築仙龛

… How can the buried bones leap across the sword lake

日下三徵終不起

Even if you beckon 3 times, I could no longer arise

That lay in Singapore enduring long thirst

Flying flowers realized their butterfly past life

Caressing the epigraph, thoughts stop and future generations

If you don’t believe just look at the tomb grass

88 old man Seok Wan

I stand before him, silent, in respect and awe.

His genes embedded in every cell of mine

We are bonded though the course of time.

A white stake declares a foreboding future

His eyeless sockets shedding copious tears

That eight lane highway: unspoken fears

“Could you not ask them to let us rest in peace”

His silenced tongue in eloquence loudly says

His bony hands grasp me in one last fond embrace.

by Lim Su Min 林蘇民 in tribute.

The prolific Khoo is responsible for composing epithets for luminaries buried at Bukit Brown. Among them the father of Khoo Teck Puat, Khoo Yang Thin. His epithet is an exhortation to the descendents through a list of things to do to live a good, honest and honorable life.

Discernible beneath the grime there is true grit Khoo Yang Thin’s grave can be found in group 12 on the map (photo Perry Tan)

Another example is the epithet for Wee Teck Seng’s tomb (just below Gan Eng Seng):

Khoo Seok Wan was also responsible for popularizing the term Sin Chew which is a sobriquet for “Singapore” (translated) Khoo writes: Singapore is an island surrounded by the sea, and with vessels and boats large and small anchored around it; the glitter of artificial lights at night are like a crown of illuminated stars (“星”) when viewed from afar. “洲” (zhou, island) and “舟” (zhou, boat) are homonyms: while the boat lights are like stars, those on the island are like the Big Dipper to accentuate the constellation. This is why the term “Sin Chew” is widely known by folks here and afar.

Editor’s note: In the first posting of this article, Lim Su Min our tea master, believed Khoo Seok Wan to be his great great grandfather based on initial evidence. Further investigation has shown this trail to be false. But in the spirit of paying tribute to Khoo Seok Wan the poet, we are leaving in this post the poem composed by Su Min.

New activity for this Sunday, Eco Stations with Beng Chiak of Nature Society, hunt down ants and insects and understand their relationship to plants and trees, how trees host other living things and nature’s self help system! Check out more details here

Family Day, we did it last Sunday on March 11 and we now know we can do it even better. Up sized buffet of activities from guided tours to treasure hunts, to arts and crafts, haiku composing for all ages and nature gems for the whole family. Adults must be accompanied by children for treasure hunts!

Please read handy tips for a more enjoyable day, there will be a quiz before you can join – just kidding – but do, DO read it for safety precautions!

The event begins at 9 am and will end by 12.30 pm.

Tours will be done differently, instead of one long guided tour, there will be 4 stations to stopover and participants may drop out anytime they want to sample other delights. Student volunteers will usher participants from station to station in 2 rounds of tours one starting at 9 am and the second at 9.30 am. They will also point out directions to those who want to return to the roundabout.

Please download this map and take note that the 4 stations covered in the route are group 1, group 3, group 4 and group 12. Constraint by time guides may not be able to cover every tomb in each group. The estimated schedule if you visit every station is 2 hours. This is the timetable with estimated times and guides :

9.oo at Sikh Station – introduction by Catherine (Second tour starts at 9.30 am if there are more than 10 people and follows the same schedule as tour 1)

a)9.15 at group 1 – by Peter (second tour eta 9.45)

b)9.50 at group 3 – by Raymond (second tour eta 10.20)

c).10.30 at group 2 – by Yik Han (second tour 11.00)

d) 11.10 at group 12 – by Charles, this last station will be capped by a short uphill (easy) to the jewel in crown Ong Sam Leong’s family grave site and group photo. ( the second tour eta 11.50 will be led Catherine and Peter )

This gives you some idea what some of your guides look like:

For the treasure hunts starting at 9.30am, look out for :

Your Emeritus Zoo Keeper of Bukit Brown – She is responsible for collecting “animals” for the treasure hunt and the design.

Watch this space for more details of Family Day activities by co-organisers: SOS Bukit Brown and Nature Society, Singapore

Recent Comments