Today marks the 70th anniversary of Lim Bo Seng’s martyrdom (29 Jun 1944)

An excerpt from Singapore war hero Lim Bo Seng’s diary:

“My duty and honour will not permit me to look back. Every day, tens of thousands are dying for their countries. You must not grieve for me. On the other hand, you should take pride in my sacrifice and devote yourself to the upbringing of the children. Tell them what happened to me and direct them along my footsteps.”

Family members attended a remembrance ceremony organised by Changi Museum, at the Kranji War Cemetery this morning.

Read the Today report here

by Norman Cho

In 2011, I discovered the grave of my paternal grandfather, Cho Kim Leong at Bukit Brown Cemetery. Since then, I have been trying to locate the tomb of his father, Cho Boon Poo (Cho Poo), who was laid to rest in Malacca. I had absolutely no clue as to which cemetery he was buried. Bukit Cina and Jelutong cemeteries came to mind but these are huge cemeteries with more than a hundred thousand graves each. They are maintained by the Cheng Hoon Teng Temple but pre-war records are unavailable. It seemed that I had hit a dead-end!

However, miracles do happen. To me, these are little blessings from above. Perhaps, the old man had wanted his descendants to visit him and had influenced how things turned out. It must have been decades since the last time any descendants paid their respects at his tomb. He must have known my sincerity and had helped me along without my knowledge. The breakthrough came in April 2014. A relative whom I had never known, contacted me via Facebook to introduce himself as the maternal great-grandson of Cho Poo, after he had discovered that we have matching ancestors from an online Family Tree software on the internet. 70 year old Vincent Lee was descended from Cho Poo’s eldest son, Cho Kim Choon, while my paternal grandfather, Cho Kim Leong, was the third son. He resides in Australia and was planning a trip down to Singapore in April 2014. He requested my assistance to put him in touch with the relatives in Singapore.

It turned out to be a blessing for me! I talked to my eldest aunt, Rose Cho (88 years old), to ask for the contacts of other relatives from the Cho clan. That was how I found aunt Elizabeth Cho (62 years old), who was the only child from the fifth son, Cho Kim Hock, a famed state badminton player for Malacca in the 1930s. We organised a dinner for our overseas relative and his wife. During dinner, I had a nice chat with Elizabeth – whom the family affectionately calls Bert – about Cho Poo. She told me that her only visit to his grave was when she was a child of 9 years old. That was more than 50 years ago! Her father who was the only surviving son at that time dreamt of his father asking him why he had not visited him in such a long time. Heeding the call, he brought his wife and daughter to pay their respects to his father. Since then, he had visited the grave alone every year till several years before his death in 1990.

Aunt Elizabeth, had the memory of an elephant! She vividly recalled that the cemetery was about a 40-minutes-drive from the Malacca Town, but had no inkling about the name of the cemetery. She further described that the cemetery was sliced into two by the main road, there was a cemetery on the left and another on the right, and Cho Poo’s was on the right. The tomb was relatively large and on a gentle-sloping plain. It faced a vast and beautiful paddy field. She added that the cemetery was on the land which once belonged to Cho Poo and was probably the private burial ground of the Cho family. Later, when the family was not doing well financially, it was sold to the Malacca’s Eng Choon Hway Kwan and it became a cemetery for the Eng Choon community. She thinks that the tomb should still be there, given the leisurely pace of development in Malaysia. She asked if I would be able to find the tomb. I told her that I could try. All her clues were useful, except for the paddy field. I told her that I doubt the paddy field in her memory still exists. Nevertheless, I took whatever clues that I could use and converted them into intelligent information.

Firstly, I eliminated Bukit Cina as it was near Malacca Town and therefore could not be a 40-minutes-drive. Next, I looked at the map of Jelutong cemetery but it was not sliced into two by any road. I asked a few Malaccan friends of other lesser-known cemeteries and searched the Google Map for them. Finally, I found a relatively small cemetery, probably no larger than 20 acres, which was dissected by a main road. It was away from the Malacca Town and would probably take about 30 minutes to get there by car. This was the Krubong Cemetery. To be certain that I had located the correct cemetery, I contacted a Malaccan friend who verified that this cemetery is indeed managed and owned by the Eng Choon Hway Kwan. He helped me to obtain the mobile contact of the tomb-keeper to locate the grave. With modern technology, I communicated with the tomb-keeper via Whatsapp to economize on the phone bill. Amazingly, he found the tomb the very next day. The search was completed successfully in less than a week since I started piecing the information together!

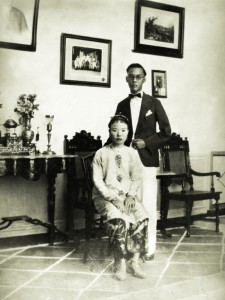

I informed aunt Elizabeth who was extremely excited and delighted with the news. We decided to go on a trip to Malacca to pay our respects to our common ancestor, Cho Boon Poo. He was the first ancestor who came to this part of the world to carve a better life for himself and his family. By braving the elements to come to the land across the Southern Seas, he had changed his destiny and that of all his descendants. It was through sheer grit and hard work that he built a successful business and owned vast plantations in Malacca and Seremban dealing in palm leaves, gambier, tapioca and rubber. We all had to be grateful to him for being able to lead good lives in Malaya and Singapore for six generations and counting. He married nyonya wives and that was how my Peranakan roots came about. Being a strict father, all his children were well-brought up and a few of his descendants took on key positions in the civil service.

I was told how strict he was about punctuality. The family would have dinner at 7pm sharp and everyone was expected at the table. Nobody could join in once dinner was served. If you missed dinner, it meant that there would be no dinner for you. During one occasion, his fourth son, Kim Tian came home late but the kind servant saved some food for him. When found out, the servant was sacked. He had a strong character and was on the board of the executive committee of the Eng Choon Hway Kwan.

We arrived at his grave on the morning of 23 June 2014 and I noticed that his tomb was the largest amongst the 50-odd tombs in the vicinity.

What captivated me were the Peranakan tiles (Majolica tiles) which adorned his tomb. No other tombs in the surrounding area had this feature. I was told that having Peranakan tiles on the tombs was not widely popular with the Malaccans. Unlike in Singapore, figurines of the Golden Boy and Jade Maiden were conspicuously absent in Malaccan tombs of even the very wealthy. The tomb used to face water-filled paddy fields which are supposed to be auspicious – water and rice. Unfortunately the paddy fields had since given way to modern development. Cho Poo’s tomb seems to be steep in Fengshui elements : the front courtyard of the tomb forms part of a hexagon instead of the normal rectangle or semi-circle. Along the perimeter of the front courtyard lies a water catchment channel which would collect water when it rains. This had since been covered with soil. The tomb shoulders are angular but eventually taper to form convoluting arms that seem to embrace the courtyard. Likely, it symbolizes a firm hold on wealth.Through the tomb inscriptions, I found the names of one of his wives (Lee Hong Neo) and that of the male descendants – sons, grandsons and even great-grandsons! He died at the age of sixty-nine in 1930. My aunt offered joss-sticks and joss-paper as a form of respect to our ancestor.

This trip has been very fruitful not only about finding out more about Cho Poo and paying our respects to him, but it has built a closer bond between aunt Elizabeth, her husband and I, even though we had known each other only recently.

More on Norman Cho’s journey of discovery, here

Family photo taken with the tomb-keeper. (L-R): Norman Cho, Elizabeth Cho-Tan, Peter Tan, Tomb-keeper Liow. (photo Norman Cho)

“Moving House”

The Story behind the Painting

by Alvin Ong

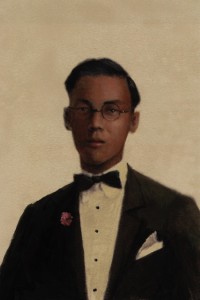

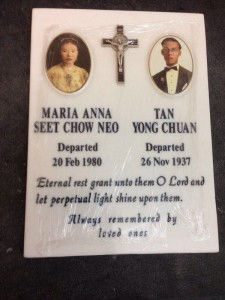

The story of 3 affected graves at Bukit Brown not too long ago inspired a revival of family interest; Tan Yong Chuan (Blk 4, Div C), Tan Tiam Tee (Blk 3, Div B), Wee Geok Eng Neo (Blk 4, Div 6) were exhumed in May 2014. Old photos were unearthed from family albums, and heirloom objects from another era suddenly came to light. For the first time in decades, stories and narratives unlocked themselves from these objects and brought new layers of meaning to the notions of home and identity.

Tan Tiam Tee was the son of the magnate Tan Hoon Chiang (buried in Bukit China, Malacca), one of the founders of the Straits Steamship Co. His wife, Wee Geok Eng Neo, and his son, Tan Yong Chuan were all affected by the proposed highway.

(click on images for a bigger view)

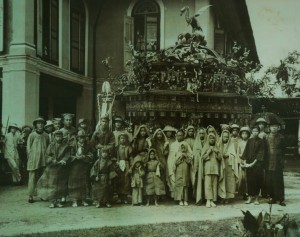

Funeral of Wee Geok Eng Neo, nee Mrs Tan Tiam Tee. Upper Thompson Rd, 1926. (photo courtesy of Alvin Ong)

Funeral of Tan Yong Chuan, died age 29, 26 November 1937, Neil Road. (photo courtesy of Alvin Ong)

Descendants at the tomb of Tan Tiam Tee, holding his portrait during Cheng Beng -tomb sweeping festival, 2012 (photo courtesy of Alvin Ong)

Descendants at the tomb of Tan Yong Chuan, Cheng Beng-tombsweeping festival , 2012 (photo courtesy of Alvin Ong

Miniature cooking pots were interred in Mrs Tan Tiam Tee’s tomb, presumably for her to cook in the afterlife, along with a pearl sanggul, and bracelets. According to my relatives, a set of gold teeth with an engraved heart shape was also found in Tan Yong Chuan’s tomb.

****

Tan Yong Chuan (son of Mr and Mrs Tan Tian Tee) was finally reunited with his wife for the first time in Holy Family Columbarium after 77 years. The columbarium has an unusual regulation that all photos of the deceased must be in color.

No color photographs of the deceased had existed at that time, so with the help of numerous correspondences, scans were digitally emailed, and the photos doctored and hand-painted.

Studying overseas has allowed the artist the space, physically and emotionally, to explore ideas of home and identity. These graves were only re-discovered shortly after the redevelopment plans were announced. The sight of the many abandoned tombs on the artist’s first visit to Bukit Brown had sparked questions about what happened to the descendants of the people who were interred there, which in turn, prompted the artist to explore if there were indeed any family connections to the cemetery at all. Beyond the historical and material significance of the place, it also felt like a site where mystery, the past, and present all came together. Reuniting with the tombs for the first time in many years became an emotional moment for some, and it also made us feel as though we have touched history, an experience that is becoming exceptionally rare in Singapore.

These were ideas that all came together in the painting, which were almost auto-biographical in that they featured vignettes of the artist’s experience with the discovery of the pioneers of Singapore and his roots. One random memory was a trek with Raymond Goh to Seah Eu Chin’s grave; One of the Teochew stone lions guarding the perimeter of the tomb eventually found its way into the picture. Raymond was featured in the early stages of the work, but in the end, this idea of displacement, loss and discovery surfaced in the final version titled, “Moving House”.

This is not the end of the road. There is yet another tomb whose story remains waiting to be told, my maternal great grandfather, Peck Mah Hoe, pictured here. The artist will be heading to the Peck clan temple in attempt to uncover more. And hopefully, there will be more paintings to come.

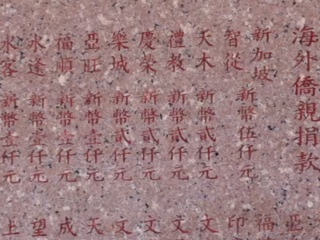

Stele in Peck clan temple with the name “Peck Mah Hoe” at the top, although the character for “Hoe” differs from the one on the tomb. Photo courtesy of Yik Han.

******

About the writer who is an artist :

Alvin Ong is reading fine art in Oxford, and did architecture at the National University of Singapore. In 2004, he was the youngest winner of the UOB painting of the year award at the age of 16. He had his first solo exhibition at 17, in the presence of His Excellency President S R Nathan.

by Ang Yik Han

Born in Kulangsu Island off Amoy, Chua Chwee Oh came to Singapore at the age of 14. He studied till 17 or 18, after which he went into business. Beginning with trading between Singapore and Medan, he founded the firm Hock Heng in 1920 which had branches in Rangoon, Annam and other cities. It dealt mainly in local produce like dried fish and provisions. The biggest segment of his business was in French-controlled Annam, followed by British Malaya and the Dutch Indies. He was the second chairman of the Amoy Association (1940-1941) after its founding, and also a chairman of the Goh Loo Club.

Active in the China Relief Fund’s efforts in raising funds to support the Chinese forces against the Japanese, he was known for donating $100,000 single-handedly under his firm’s name. He also encouraged others to contribute by setting an example when the need arose. It must have been a bitter blow for him during the Japanese Occupation when he was forced to join the Hokkien section of the Overseas Chinese Association (OCA), the umbrella body set up by the Japanese to force the Chinese community to pay war reparations.

Chua Chwee Oh died in 1960 at the age of 64. His first wife Mdm Tan passed away at the young age of 32 and is buried together with him. His second wife was Mdm Ng. The place of origin inscribed on his tombstone is “Si Ming” (思明), another name for Amoy coined by Koxinga when the island was his base of operations against the encroaching Qing forces. This name evokes Koxinga’s longing for the glory days of the Han Chinese Emperors in the Ming Dynasty. Barred from use after the Qing Dynasty consolidated its control over all of China, this place name was revived after the Qing Dynasty was overthrown.

The tomb is at Hill 3, about 10m behind and to the left (facing uphill) of Tan Boo Liat’s tomb.

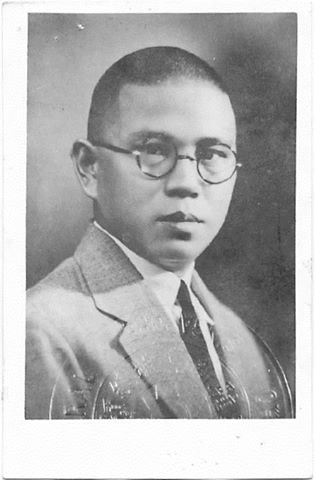

Tan Ean Teck (1902-1944)

According to “Biographies of Famous Personalities in the Nanyang,” Tan Ean Teck came to Singapore from Tong Ann, China at the age of 16. He worked for about four years in his brother’s (Tan Ean Kiam) company before striking out on his own, setting up his own rubber trading firm.

He was a strong supporter of the anti-Japanese war effort in China, and contributed to charitable causes in both China and other lands. He also contributed to the Hokkien Huay Kuan, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the Tong Ann District Guild, as well as many schools and social institutions,

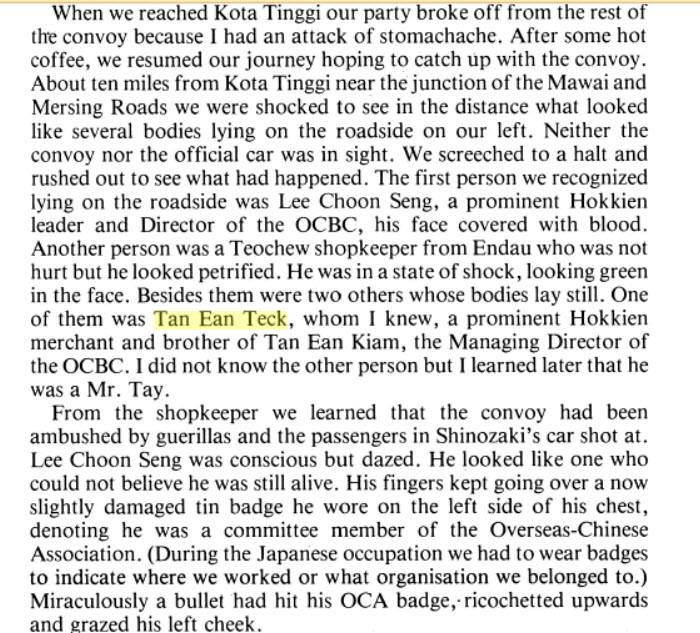

But Tan Ean Teck’s life was tragically gunned down when he became a casualty of WW 2. On 19 April, 1944, the MPAJA (Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army) ambushed officials of the OCA ( Overseas Chinese Association) en route to visit the Chinese settlement of Endau in Johor.

A member of the OCA convoy, captures vividly what happened:

Tan Ean Teck’s body was taken back to Singapore and 4 days later on 23ed April , he was buried in Bukit Brown, close to his brother Tan Ean Kiam. He was 42 years old.

Prologue: Endau and World War II

In August 1943, in order to ease the food shortage problem in Singapore, the Japanese authorities mooted the idea of setting up new settlements outside Singapore and encouraging Singaporeans to relocate to these settlements to cultivate the land there. These settlements were planned to become self-sufficient in food supply. A settlement was created for Chinese settlers at Endau in Johore. (Source: Iinfopedia)

From Alex Tan Tiong Hee

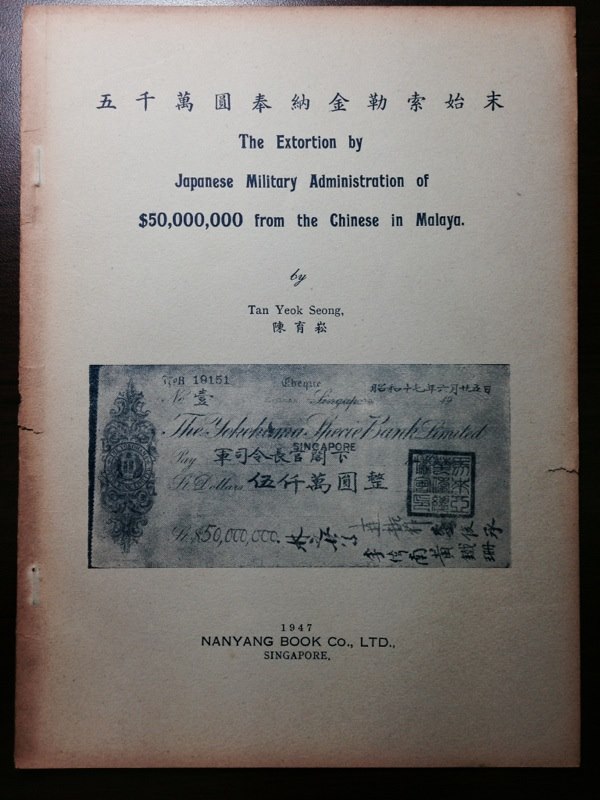

My understanding, based on my late father’s (Tan Yeok Seong) account:

The OCA was not popular with the anti-Japanese elements that went underground to survive. Those living an open unconcealed life in public were natural targets for the Kempeitai who sought revenge against the Chinese, hence the pogrom.

The pacification of Japanese antagonism was the OCA’s raison d’etre and which had to be traded by the raising of $50million from the Chinese community as a gift for the Japanese emperor’s approaching birthday. This being done, the persecution or ‘sook ching’ then ended.

The communist terrorists were enterprising enough to merge with the anti-Japanese underground group to form the MPAJA. They accused the OCA as collaborators and monitored the Endau Project. Their opportunity came when they ambushed and fired at a convoy killing all except Lee Choon Seng who was Vice President of the OCA.

Extract from Collaboration during the Japanese Occupation : Issues and Problems focusing on the Chinese Community by Han Ming Guang (Hons thesis for history):

Even though Endau was administered by the Chinese, the fact that it was sponsored by the Japanese military and established by the O.C.A whom the MPAJA saw as an organisation of collaborators, meant that the Chinese administrators that administered the settlement were now targets for the MPAJA guerrillas. The MPAJA guerrillas ambushed the O.C.A officials that were on their way to visit Endau and in the process wounded Mr Lee Choon Seng, the chairman of the Overseas Banking Corporation. They also managed to kill Mr Wong Tatt Seng, who was in-charge of maintaining peace and order within the settlement, along with other Chinese administrators who were also living in Endau at the time of the attacks.

While it was clear that the MPAJA viewed the members of the O.C.A as well as the Chinese leaders of Endau as collaborators and traitors, in general the people who were living in Endau did not share those views. They understood that the Endau plan was conceived by the O.C.A and Mamoru Shinozaki in order to save Chinese lives from the dreaded Kempeitai , by giving the Chinese community a piece of land in Johore, for them to live separately and free from the Japanese military.

Pat Lin on life in Endau:

According to my parents, Maggie Lim and Lim Hong Bee (H.B. Lim) both of whom were actively involved with the MPAJA in the Endau settlement (Yes, I was there too) there were people in the OCA who were what we may today call double agents. They included some very prominent local people who on the surface professed to be anti-Japanese, but who were informers who were usually rewarded by the Japanese.

As with the French resistance, it was a very difficult time as people all lived under a climate of uncertainty as to who was about to betray them to the Japanese. My mother also had her suspicions as to those who carried out the covert assassination of informers.

She has a vivid story of having to deal with someone who was brought into the Endau clinic (she was the Endau doctor) one evening with a bullet in his head. As a physician she was duty bound to do everything to save him. She was filled with the reluctance to do anything as it was known by the Endau leadership that he fed information to the Japanese that led to people being taken away for execution or disappearing suddenly. Possession of any sort of weapons was punishable by death, but people like my father possessed hand guns that they somehow received from some source and were very carefully hidden.

Endau was located in healthier environs and there were more people who managed to make a go of farming. The staples were kangkong and ubi kayu. My little family brought chickens up from Singapore piled up In chicken coops on top of a lorry. Some of them ran off into the jungle, and others fell prey to wild animals. Wild animals including roaming tigers were a real threat.

The first year in Endau and Bahau were particularly bad before the first harvests. OCA members from Singapore would make periodic visits with whatever they could scrounge up including medicines. Some within the community tried being entrepreneurial by trying to sell black market food stuffs they somehow managed to obtain. Mom recalled being so hungry from having to work and nurse me but my father being ever the man of high ethical standards refused to allow the purchasing of black market goods.

An Epilogue on a Life Miraculously Saved

The metal badge of the OSA worn on the chest, deflected the bullet that could have fatally wounded the Vice President of the OSA, Lee Choon Seng. He believed he was saved for a reason and his life took on a spiritual quest in the aftermath of war. Lee Choon Seng subsequently founded the Poh Ern Shih to dedicate merits to people killed during the occupation. His grandson transfromed the monastery into Singapore’s first green temple.

***********

Editor’s Acknowledgement : This blog post is a compilation of first hand accounts and research from the Heritage Singapore Bukit Brown Facebook Community.

by Ang Yik Han

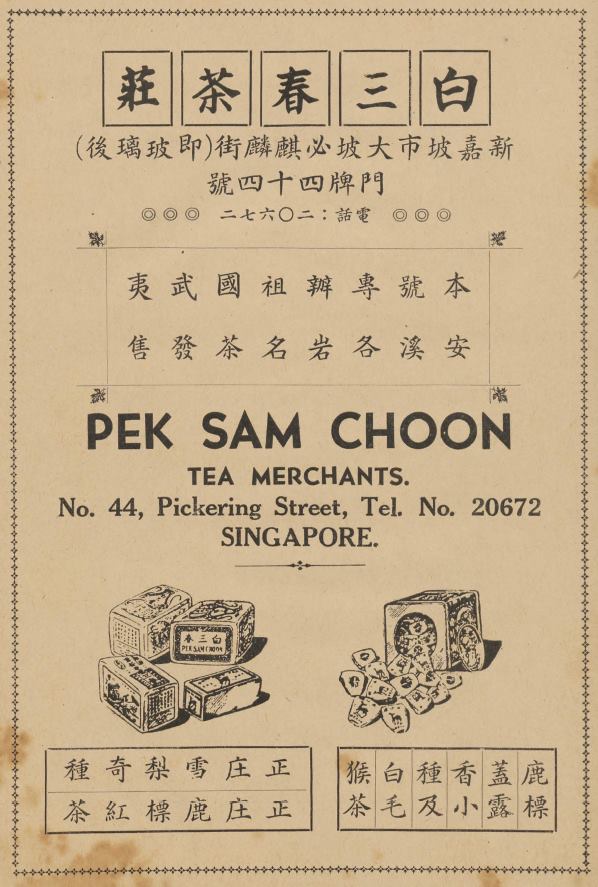

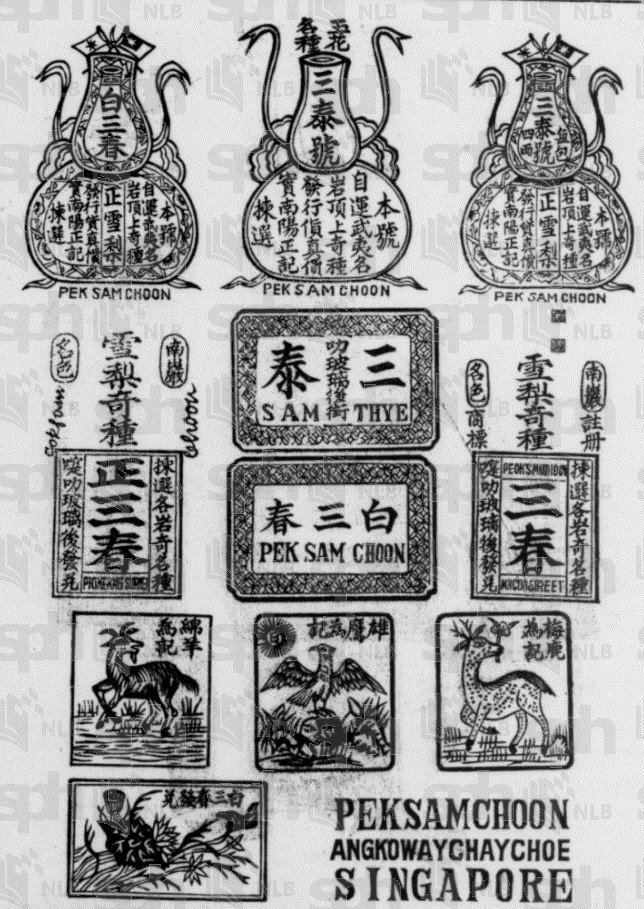

The tomb of 白心正 (probably Pek Sim Jia in romanised Hokkien) at Hill 3. Hailing from Anxi (安溪 – An-khoe) county of Fujian, he was the proprietor of Pek Sam Choon (白三春) – a tea importer who was one of the founding members of the Singapore Chinese Tea Importers and Exporters’ Association in 1928.

No longer in operation today, the firm was known to still exist in the 1950s when it was run by one of his sons, Thiam Hock, whose name appears on his tombstone. As Anxi county is famed for producing tea especially Ti Kuan Yin (铁观音), a sizable proportion of local Chinese tea merchants hail from that county. Some old firms founded before the war are still around today.

Advertisement for Pek Sam Choon in the 30th anniversary commemorative publication of Singapore Ann Kway Association 1952

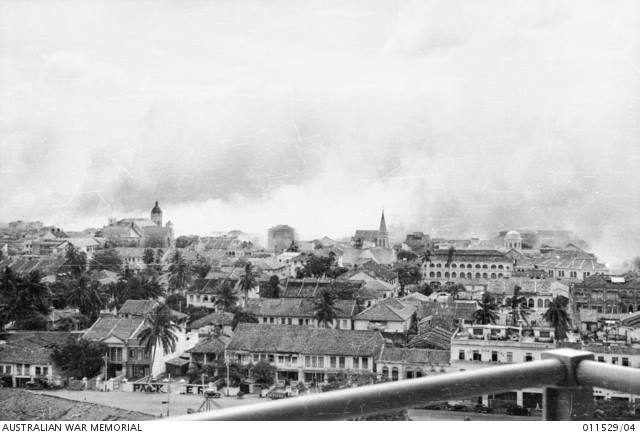

This chronology of the Japanese invasion was compiled by James Tann, a heritage blogger, in the lead up to the 72nd anniversary of the fall of Singapore on 15 February, 1942.

Feb 8, 1942.

The Japanese Army invasion of Singapore Island begins with the crossing at Lim Chu Kang.

February 9, 1942.

Having landed the night before along the Lim Chu Kang coast, by the afternoon of 9th Feb, Tengah Airfield was in the hands of the invading Japanese Imperial Army.

Also on 9 Feb, the Japanese Army opened a 2nd battle front by landing the Imperial Guards Division at Kranji and the Causeway. This Division was to move east heading towards the Sembawang & Thomson regions.

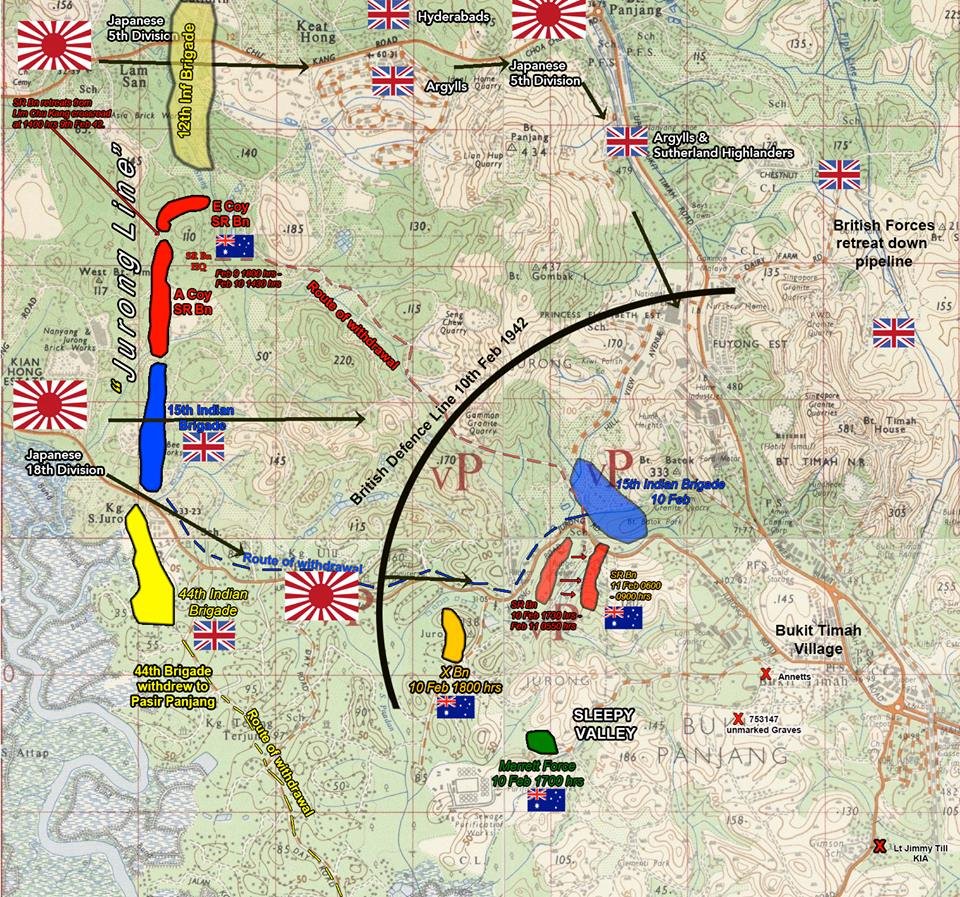

The Jurong-Kranji Line – 9th February, 1942.

The Allied forces formed a futile blockade called the ‘Jurong Line’ stretching east of Tengah Airfield, through Bulim to the Jurong River (where Chinese Garden is today) to try and contain the Japanese forces within the western sector of Singapore.

By evening of 9th Feb 1942, the Jurong Line had collapsed completely due to miscommunication. The main Australian 22nd Brigade retreated, resulting in a domino effect leading other units to retreat as well.

Luckily for them, the Japanese forces did not press their advantage as they had to wait for reinforcements and logistic supplies to follow up across the Straits to continue the invasion.

You can also read how a jungle dirt track saved the lives of 400 soldiers by James Tann here

10th Feb 1942.

The capture of Bukit Panjang and the massacre at Bukit Batok.

With the overnight collapse of the ‘Jurong Line’ blockade, the Japanese 5th Division easily manoeuvred down Choa Chu Kang Road and overpowered the defences by the Argylls & Sutherland Highlanders and the Hyderabad Regiment at Keat Hong. Pushing them back all the way to Bukit Panjang Village. It was the first encounter with Japanese tanks in Singapore by the British.

By the early afternoon, Bukit Panjang Village had fallen to the Japanese. Some British units managed to escape through the farmlands of Cheng Hwa and eventually followed the water pipeline down to British lines near the Turf Club region.

Intending to re-establish the ‘Jurong Line’, the British High Command despatched 2 battalions from Ulu Pandan to Bukit Batok (West Bukit Timah).

X Battalion made it way to 9ms Jurong Road (opp today’s Bukit View Sec Sch), while Merret Force lost its way and camped at Hill 85 (Toh Guan Road today).

The Japanese 18th Div coming down Jurong Road encountered both X Battalion and Merret Force during the night. X Bn, caught totally off guard, was annihilated and lost over 280 men, while Merret Force had half its force killed in the ambush.

The Japanese Commander, Gen Yamashita, had ordered both his 5th and 18th Division to take Bukit Timah Village and Bukit Timah Hill by the 11th Feb. Thus, both units were in a frenzied rush to capture the strategic high point.

By midnight of 10th Feb, Bukit Timah Village was ablaze and effectively conquered by the invasion force.

Photo credits: Australian War Memorial

1. Japanese soldiers at Bukit Timah Hill

2. Japanese Type 95 HaGo Light Tanks in Bukit Timah Village

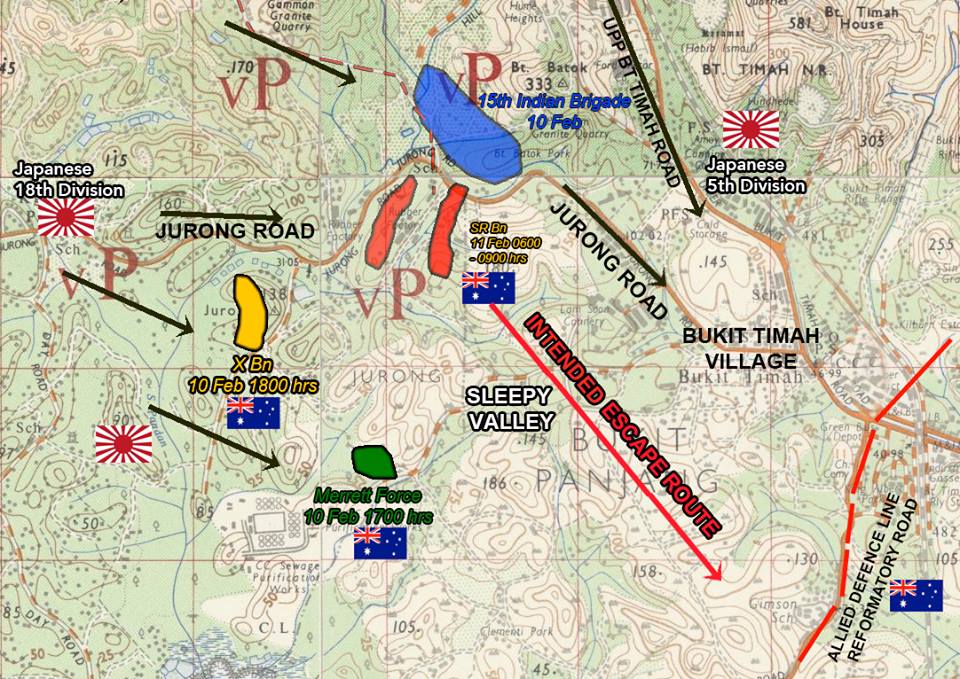

11th February 1942.

The Fall of Bukit Timah Hill and the Tragedy at Sleepy Valley.

By the time Gen.Yamashita’s army crossed into Singapore, he was critically short of supplies, fuel, ammunition and even food for his troops. His strategy was thus to conduct a tropical blitzkrieg – ‘hit them fast hit them hard’ – to capture Bukit Timah. It being the high point for observation also held the British ammunition, food and fuel depots which he coveted.

To raise morale of his troops, he set Feb 11 as the day to capture Bukit Timah Hill. The significance of Feb 11 was that it was the Japanese Kigensetsu, the day they celebrate the ascension of the 1st Emperor and the founding of the Japanese Empire. The task was assigned to competing 5th and 18th Divisions with untold glory going to the unit achieving the objective first.

By midnight of 10th Feb, both units had already reached Bukit Timah Village and the resultant battle against the British defenders set the entire region ablaze. The British retreated and held their line at Reformatory Road (Clementi Road)

By early morning of the 11th, the Japanese had secured Bukit Timah Hill.

Meanwhile back at Bukit Batok…

By the morning of 11 Feb, the senior commander of 15th Brigade, Brigadier Coates, who was to lead the re-taking of the Jurong Line, knew that the Japanese had surrounded his position. He cancelled the order and proceeded to retreat, together with the Special Reserve Battalion, back to allied lines at Ulu Pandan.

Forming 3 columns consisting of 1500 men from the British, Indian and Australian units, they proceeded from Bukit Batok to cross an area called Sleepy Valley.

Unknown to them, the Japanese 18th Division was already waiting to spring their trap on the British soldiers.

What happened next is a seldom mentioned debacle which actually had the highest number of casualties of any skirmish within Singapore during the war. The firefight that took place at Sleepy Valley took the lives of 1100 allied soldiers out of the 1500 who entered that valley of death.

Throughout the day, the British sent in reinforcements to try and re-take Bukit Timah. However, both Tomforce and Massey Force could do little to dislodge the Japanese.

When Bukit Timah Hill fell, Gen Percival moved his HQ from Sime Road to Fort Canning. The fear of the approaching Japanese Army also led them to destroy the infamous 15” Guns at Buona Vista Camp at Ulu Pandan that morning. It was a sign that things had come to bear…

12th Feb 1942.

Yamashita’s Ultimatum.

Tomforce’s attempt to re-take Bukit Timah and Bukti Panjang ended in futility. Unknown to them, they were up against the battle hardened Japanese 56th and 114th Regiments of the 18th IJA Division, Yamashita’s crack troops, who had fought all the way from China.

By the morning of 12th Feb, the British lines were being pushed backed.

Tomforce fell back from Reformatory (Clementi) Road to Racecourse when the Japanese overran the supply depots at Rifle Range. By the end of the day they would retreat all the way back to Adam and Farrer Road.

By then, Gen Percival had redrawn the defence line.

Massey Force would protect the waterworks from Thomson Village to the east of the MacRitchie golf links, where the former HQ at Sime Road was.

Gen Heath’s British units would fall back from Nee Soon, having abandoned the Naval Base, and form the line from Braddell to Kallang.

In the west, the Australians fell back from Reformatory Road to Holland Road (Old Holland Road), while the 44th Indian Brigade formed the line from Ulu Pandan to Pasir Panjang. Sporadic fighting occurred throughout the day along the line.

Elated with the capture of Bukit Timah, Gen.Yamashita was still faced with logistical problems including a critical shortage of ammunition. He knew he wouldn’t be able to last out in a war of attrition and thus resorted to his plan to bluff the British into surrendering, by dropping ultimatum notes into the British lines.

“To the High Command of the British Army, Singapore”

I, the High Command of the Nippon Army have the honour of presenting this note to Your Excellency advising you to surrender the whole force in Malaya.

My sincere respect is due to your army…bravely defending Singapore which now stands isolated and unaided…..futile resistance would only serve to inflict direct harm and injuries to thousands of non-combatants….Give up this meaningless and desperate resistance…If Your Excellency should neglect my advice, I shall be obliged, though reluctantly from humanitarian considerations to order my army to make annihilating attacks..”

(signed) Tomoyuki Yamashita”

Getting no response to his ultimatum message, Yamashita sent his units on probing incursions along the line.

These took place mainly at Sime Road and Pasir Panjang near Normanton.

He had no intention to enter the city as he knew he did not have the resources to fight a street to street battle.

Major Bert Saggers was CO of the Special Reserve Bn that was ambushed at Sleepy Valley. He survived and made his way to Ulu Pandan where he found only 80 of his 420 men alive but all his officers killed. (photo Ian Saggers, Perth Australia )

Lt Jimmy Till was an officer in Bert Sagger’s unit. He was buried near the spot where he was killed. This was near where today’s Ngee Ann Polytechnic Alumni Clubhouse stands. Picture is his grave now at Kranji War Memorial. (photo James Tann)

13th Feb 1942.

The noose tightens around Singapore City.

With the core of Singapore Island firmly in the hands of the Japanese Army, Gen.Yamashita moved his HQ from Tengah to the Ford Motors factory at Bukit Timah.

Strangely, the previous day ended somewhat with a lull in the fighting.

This allowed Gen Percival to continue finalising his last line of defence.

From Kallang Airfield to Paya Lebar, Paya Lebar to Braddell, Thomson Village to Adam Park, Adam Road to Farrer Road to Tanglin Halt, from Buona Vista across Pasir Panjang ending at Pasir Panjang Village.

The last unit to pull out , the 53rd Brigade, left Ang Mo Kio area around noon and the traffic along Thomson Road was so choked that Japanese planes had an easy time strafing the columns along the route.

Gen.Yamashita had actually feared that Gen.Percival would dig in and fight to the last.

In order to continue his feint, despite running low on ammunition and men, he launched attacks to give the British the appearance of Japanese strength.

He ordered the crack 18th Division to take Alexandra Barracks and the 5th Div & the Imperial Guards to attack the Waterworks at MacRitchie and the pumping station at Woodleigh.

Alexandra Barracks was the main British Army Ordnance Depot, where most of their equipment, stores and fuel storage, as well as the main Alexandra Military Hospital, were located

The attack on Alexandra Barracks began from Pasir Panjang (Kent Ridge) after 2 hours of heavy shelling at noon.

Waves of Japanese soldiers fought determined defenders from the 1st Malaya Brigade and the 44th Indian Brigade. Fighting was vicious and often hand to hand. The Malay Regiments were slowly overpowered with the Japanese winning height after height. The Gap, Pasir Panjang Hill III, Opium Hill, Buona Vista Hill, would fall one after the other but fighting would continue till the following day.

Over at MacRitchie, the Japanese 5th Division fought the 55th Brigade (1 Cambridgeshire & 4 Suffolk Regiments) to gain control of the reservoir. An all night tough fight including tanks forced the British Regiments all the way back to Mount Pleasant Road across Bukit Brown cemetery. The Suffolks lost over 250 men defending their ground.

The Japanese Army was now within 5 kilometres of the City on 2 fronts.

All this while, civilians casualties were mounting in the collateral damage from the Japanese shelling.

The City now had up to 1 million evacuees, most in dire straits without shelter, food nor water.

An Officer was to record travelling down Orchard Road:

“Buildings on both side went up in smoke…civilians appeared through clouds of debris; some got on the road, others stumbled and dropped in their tracks, others shrieked as they ran for safety. We pulled up near a building which had collapsed, it looked like a slaughter house; blood splashed, chunks of human being littered the place. Everywhere bits of steaming flesh, smouldering rags, clouds of dust and the groans of those who still survived.”

At the Battlebox, the new HQ at Fort Canning, Gen.Percival and his senior commanders were contemplating the latest orders from Gen.Wavell as well as an order from Churchill.

14th Feb 1942.

Prelude to Capitulation

Throughout the night of 13/14th Feb, sporadic skirmishes occurred both at Pasir Panjang and Adam Road.

At daylight 8.30am at Pasir Panjang Ridge , the Japanese charged up for a final assault on Hill 226 and Opium Hill facing heavy resistance from the 1st Malay Regiment. Bitter hand to hand combat lasted till 1.00pm in the afternoon when the Japanese gained control of the hills and in the process annihilating the Malay Regiment.

As the loss of the strategic ridge gave way, the Japanese advanced along Ayer Rajah in pursuit of Indian troops towards the British Military Hospital. It was then that the tragic incident occurred at the BMH with the senseless slaughter of wounded patients and medical staff.

There was also little relief along Adam Road. The Japanese, with Col Shimada’s Tank Regiment, pressured the line with a bulge through Bukit Brown, towards Caldecott Hill and Adam Park. Bitter fighting occurred around Hill 95 and Water Tower Hill (today’s Adam Park/Arcadia).

The Imperial Guards Division harried the eastern battle line at Paya Lebar and were near to capturing the Woodleigh pump station by mid day.

At British HQ in the BattleBox at Fort Canning, Gen.Percival conferred with his field commanders.

Brigadier Simson advised that the water situation was extremely grave with the threat of epidemic.

Gen Heath, commander of British Forces, and Gen Bennett, commander of Australian Forces, urged Gen Percival to surrender. Percival refused to yield, having direct orders from Churchill via Gen.Wavell, the Commander in Chief based at Java, not to surrender and to fight to the last man.

However, Gen.Percival informed Gen.Wavell that the enemy was close to the City and that his troops were no longer in a position to counter attack much longer.

Gen. Wavell sought permission from PM Churchill to allow Gen.Percival to consider the option of surrendering.

Churchill replied to Gen. Wavell:

“You are, of course, sole judge of the moment when no further result can be gained at Singapore., and should instruct Percival accordingly, C.I.G.S. concurs”

With that, the final key was inserted into play for Singapore. (But the permission for Percival to consider surrendering did not go out to Percival until the next morning of the 15th.)

*CIGS = Chief of Imperial General Staff

Lieutenant-General A E Percival, General Officer Commanding Malaya at the time of the Japanese attack.(photo Imperial War Museum London)

General Sir Archibald Wavell, C-in-C Far East, and Major General F K Simmons, GOC Singapore Fortress, inspecting soldiers of the 2nd Gordon Highlanders, Singapore, 3 November 1941. (photo Imperial War Museum London)

15th Feb 1942.

Chinese New Year – The Year of the Horse

There was absolutely no joy in celebrating Chinese New Year in 1942. The country was in shambles.

The foreboding fear of the encroaching Japanese military, preceeded by tales and rumours of their atrocities in China all portent the unknown that lay ahead.The British masters and their families had all bugged out. What did this mean for the locals now?

A Japanese flag could he seen flying from the top of the Cathay Building! Was this the end?

For the locals, especially for the Chinese, it was going to be the start of three and a half horrifying years.

Morning of 15th Feb saw the opposing forces holding most of their ground, with infiltration mainly by the Japanese within the eastern sector reaching Kallang Airfield. In the west, Japanese troops reached Mount Faber.

Gen. Percival convened his most senior officers at the Battlebox at 9.30am for the latest status reports.

Brigadier Simson reported that water supply could not be maintained for more than a day due to breakages everywhere which could not be repaired. Water was still flowing despite the pumps and reservoir being in enemy’s hands!

The only fuel left were what remained in each vehicle and at a small pump at the Polo Club.

Reserved military rations could last for only a few more days.

With unanimous concurrence of all present, the decision to cease hostilities and to capitulate was made.

A deputation comprising Brigadier Newbigging, HQ Chief Admin Officer, the Colonial Secretary Mr Fraser and Major CH Wild as interpreter, left Fort Canning for the enemy lines at Bukit Timah Road.

At the junction of Farrer Road, they proceeded on foot with Union Flag and a white flag across the defence line for 600 yards where they were met by the Japanese soldiers. They were later met by Col Sugita who refused their ‘invitation’ to the City for negotiations. Instead, Col Sugita demanded that Gen.Percival was to personally surrender to Gen.Yamashita.

To acknowledge this condition, the British were to fly a Japanese Flag from the top of the Cathay Building.

At 5.15pm, the British surrender party drove up to the Bukit Timah Ford Motors factory.

The delegation was made up of Lt-Gen AE Percival, Brigadier Newbigging, Brigadier Torrance, Gen Staff Officer Malaya Command, and Major Wild, the interpreter from III Corps.

Though Gen.Percival tried to negotiate for some terms for his men, Gen Yamashita thought that he was playing for time and pressed Percival for an unconditional surrender, telling him that a major attack on the City was scheduled for 10.30pm that night and any delay, he might not be able to call off the operation in time.

“The time for the night attack is drawing near! Is the British Army going to surrender or not?”

Banging the table he shouted in English “Answer YES or NO.”

At 6.10 pm. Gen.Percival signed the surrender document, handing Singapore over to the Japanese Empire.

************************

Read about the Battle at Bukit Brown on 14 February, 1942, a day before the surrender to the Japanese, here

And the latest on missing soldiers here

Time 9 am – 12 pm

MEETING POINT: Junction of Lorong Halwa, Kheam Hock Road and Sime Road.

Feb 15, 1942 – Singapore, the “Impregnable Fortress” of the British Empire, falls to the Japanese invading forces.

Visit Bukit Brown Cemetery, site of fierce battles involving British (4th Suffolks) and Indian (Royal Deccan Horses) forces, near a village of Chinese and Malay civilians had lived.

Your guides are Claire and Ish Singh, and Peter Pak. Together they will help piece together an important day in Singapore history at the site, and recount personal stories of those buried there as well as an account of their families got caught up in the war. We welcome anyone with knowledge of the area and the battles fought there to join us and honour the memory of the war dead.

Disclaimer: By agreeing to take this walking tour of Bukit Brown Cemetery, I understand and accept that I must be physically fit and able to do so.To the extent permissible by law, I agree to assume any and all risk of injury or bodily harm to myself and persons in my care (including child or ward)

Registration:

Please click ‘Join’ on the FB event page to let us know you are coming, how many pax are turning up, or just meet us at the starting point at 9am.

“We guide rain or shine or exhumations.” – we urge you to wear sensible shoes, carry a bottle of water, put on insect repellent, and come with an open mind as we explore together. We share and talk as we walk, and learn from each other. Our walking tours are meant to be learning journeys, for both participants and guides. We believe in building communities and growing organically.

** IMPORTANT NOTE: GETTING THERE: http://bukitbrown.com/

Reading materials:

This was their last tour report, marking the day bombs first fell on Singapore: http://bukitbrown.com/

To read about the 4th Suffolks battling the Japanese who came across Hellfire Corner on the evening of Feb 14, 1942: http://bukitbrown.com/

To read about the Kheam Hock skirmish and massacre: http://bukitbrown.com/

Bukit Brown is the only Singapore site on the World Monuments Fund Watch List of threatened heritage sites. Read more here: http://bukitbrown.com/

Ish himself found a strong link to his Sikh roots through Bukit Brown: http://bukitbrown.com/

Claire’s TEDx talk touches on the war: http://www.youtube.com/

all things Bukit Brown will mark the weekend with tours and talks on both days. Keep an eye for updates.

By Serene Tan

Not long after my dad passed away in 2011, the government announced plans for an 8 lane highway that would cut through Bukit Brown, and graves in the way would have to be exhumed.

The news of the highway triggered a memory. The last time I visited my grandpa’s tomb was more than 40 years ago when I was a young girl. I could vividly recall my grandpa’s tomb at Bukit Brown. Concerned it might be affected, I realised it was time to visit him.

I arranged with my cousin to visit the grave for the ‘Qing Ming’ festival the next year, 2012. It was a relief to learn that his grave was not staked for exhumation. But to my dismay, the tomb was in a dilapidated condition. The tomb had been neglected for more than 15 years after my dad suffered a massive stroke which left him paralyzed and wheel chair bound.

It dawned on me then, that I now had the responsibility to carry on my father’s duty to ‘sweep’ grandpa’s tomb during the ‘Qing Ming’ festival. His tombstone spoke to my roots.

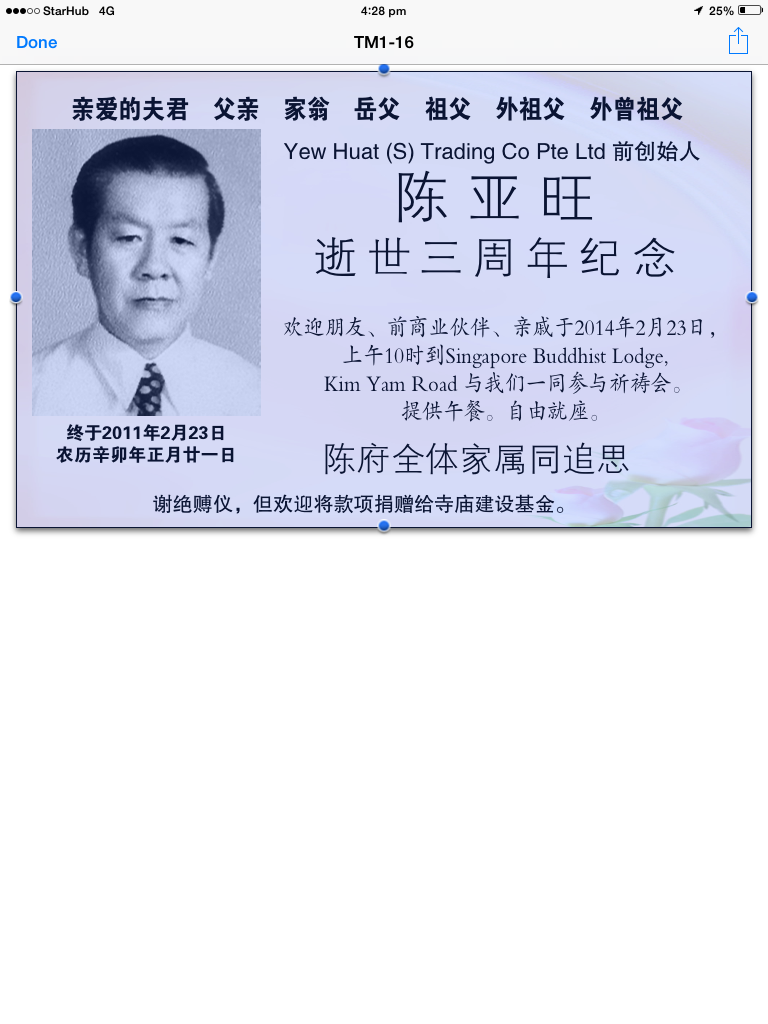

Inscribed on the tombstone was my ancestral hometown , Kimen, my grandfather’s death date, 1937, and the names of his children. My father was the only son. For the first time I came to know my father’s birth name 陈天吉, Tan Tien Kiat, inscribed on the tomb. My grandpa passed away when my dad was only five and dad changed to a simpler name, 陈 亞 旺, Tan Ah Ong

I arranged with a contractor to renovate my grandpa’s tomb, and before work started, I decided it was also time to visit my ancestral home in Kinmen, Taiwan . Unconsciously, I think I was seeking the blessings of my father and grandfather.

My grandpa Tan Teow Meng (陈 朝 明 )left his home in Kinmen, more than 100 years ago. In Singapore, I was told he worked as a lorry driver and died because of a bout of high fever.

My father had attempted to visit his ancestral home, thrice in the 80s. Kinmen is a small archipelago of islands and at that time was under a military administration because of fighting with China. The only means of transport then was by military helicopter. Visitors to the island were restricted but because Dad could claim to be descended from his ancestors in Kinmen, getting permission was not the problem. Each time, it was bad weather which prevented my father’s flight on the helicopter from taking off from mainland Taiwan.

He was so close and yet so far. I felt deeply the pain of his disappointment. Dad subsequently passed away, without fulfilling his dream.

It was in my ancestral village of Houshan (后山), now known as Bishan, that I learned my father had contributed funds to two temples. His name was inscribed on the list of donors for both temples. This one is from the smaller village temple 陈氏宗祠

I placed my father’s photo as close as I could to the inscription of his name among the temple’s donor list (photo Serene Tan)

My heart swelled with pride. There is an old Chinese saying “Drink Water, But Remember the Source”- “饮水思源” . My father, although he was not able to visit his ancestral home, never forgot his roots.

The family home and land in Kinmen, remains abandoned. But at home in Singapore, my grandpa’s tomb has been rebuilt with granite stone and fresh inscriptions in gold dust. My grandpa had a humble life his son – my father – worked hard and became a successful business man and never forgot his father. I have always admired my father for his work ethic and persistence.

So as I marked Qing Ming at my grandpa’s new “home” after my visit to Kinmen, I felt happy and blessed to have been able to accomplish my father’s dream of visiting our ancestral home.

***

My journey to my ancestral home in Kinmen in a photo essay.

My ancestral home and land, abandoned. Relatives I met told me, the home was occupied by troops during the conflict with China and they also dismantled the wooden structures to build their bunkers. ( photo Serene Tan)

The village temple 陈氏宗祠

The temple serves residents nearby to offer prayers anytime as and when they deem necessary. (陈氏宗祠)

My father also donated to the larger Tan clan ancestral temple, 陈氏 家廟. Unlike the village temple, it’s opened only for certain festival celebrations and entry restricted to only male descendants. I was privileged to be granted permission to enter, as an exception.

- In the courtyard of the Tan temple, holding a photo of my father (photo Serene Tan)

My father’s name 亜 旺 on the donors list.

4th from left is my father’s name on the list of donors from Singapore to the Tan temple (photo Serene Tan)

Meeting my relatives for the first time, I learned my great grandfather’s name is 陈 正. So he is the earliest of my ancestors I have come to know.

I will be marking my father’s third death anniversary at the Singapore Buddhist Lodge, 17-19 Kim Yam Road on 23 Feb 2014 at 10 am. Friends and relatives are welcome to join us in prayers.

Chew Chai Pin

(b. 11 November 1911 – d. 13 June 1941)

Among the 4,000 graves which will have to be exhumed to make way for the highway is that of Chew Chai Pin (# 1253)

The Grave of Chew Chai Pin ( photo credit : The Bukit Brown Documentation Project)

Chew Chai Pin was one of three founders of the Chinese High School in Batu Pahat. Unlike the other prominent Chinese men who contributed to the school, Chew was not well known then in the community. He held the concurrent position of director and teacher of the Ayer Hitam School. But he was soon to answer a higher calling.

On March 6, 1940, Chew went to China from Singapore to Yangon and China, to visit and give moral support to the Nanyang volunteer mechanics and drivers, as well as civilians and troops. The Nanyang Volunteers were recruited and trained from South East Asia, to transport war and logistic supplies through the notorious China-Burma highway to sustain China’s war effort against the invading Japanese. Chew represented Batu Pahat as part of a deputation comprising of representatives from the overseas Chinese communities of South East Asia.

But on March 29 1940, the vehicle he was in overturned and he sustained serious injury to his spinal cord. He was warded at a hospital at Xiaguan (Yunnan) while the rest of the deputation proceeded to their destinations. He was visited by none other than Tan Kah Kee, who was instrumental in galvanizing the support of the overseas Chinese in Nanyang (South East Asia) for the second Sino-Japanese War. Tan made arrangements to have Chew sent to Yangon for treatment as the doctors in Xiaguan were unable to heal him. Chew’s legs were numb and he could not walk for more than a year. Chew also received a letter of consolation from the Commander-in-Chief of the war and leader of the Kuomintang , Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek.

On March 4th of 1941, a year after his accident, an arrangement was made for him be transported to Singapore for treatment. Just when many thought Chew would recover, he died in Singapore on June 13, 1941 at 0615 hours. It was said that his funeral in Singapore was attended by more than 400 people. He was hailed in both Singapore and Malaysia as a patriot who sacrificed his life for China.

An obituary in the Nanyang Siang Pau to the memory of Mr Chew Chai Pin proclaims: “He Died for his Country”

On his deathbed, he urged his compatriots to spare no effort for China’s salvation. He said:

“I am ashamed to have done nothing in service of my country. How can I die without doing anything for the motherland? I must do something for the nation when I come back in another life.” Chew Chai Pin.

Chew was just 30 years old when he died.

Tan Kah Kee wrote in his memoirs that when the deputation left Singapore by ship on the 6th of March, it was sent off by a crowd in high spirits. Only Chew’s mother and wife were weeping. Somebody observed to Tan, that the deputation would be away for only 3 months and it was an honour to be a delegate, so even though one could excuse Chew’s mother as she was of an older generation, his wife who was educated and a teacher was showing too much emotion. After seeing Chew in hospital six months after his accident, when he could not be cured by the doctors there, Tan Kah Kee remarked that it seemed the mother and wife had been prescient of what was to come at the point of parting.

Chew was born on 11/11/11 in the Hokkien Province, Tong An County, Au To village. He married in November 1937, and was childless at the time of his death. After he passed away, his parents adopted a son on his behalf.

postscript : Chew Chai Pin’s grave has been claimed.

***

Source: From the blog of 沈志堅’who is a teacher at Chinese High School in Batu Pahat. (Translated by Fabian Tee)

Additional information from the Memoirs of Tan Kah Kee

Recent Comments