淸明- 杜牧 (唐著名詩人)

淸明時節雨紛紛 qīng míng shí jié yǔ fēn fēn

路上行人欲斷魂 lù shàng xíng rén yù duàn hún

借問酒家何處在 jiè wèn jiǔ jiā hé chù yǒu

牧童遙指杏花村 mù tóng yáo zhǐ xìng huā cūn

Incessantly the rain falls during Qingming

On the roads are travelers deep in sorrow

Where is there a tavern to be found?

The shepherd boy points to Xinghua (Almond Flower) Village in the distance

(poem by Dumu translated by Ang Yik Han)

My Cheng Beng 2012 is a photo essay by Toh Zheng Han in memory of his late Ah Chors (great grandparents), Ah Kong (grandfather) and Ah Ma (grandmother) It marks his family observance of the festival and perhaps a coming of age for him in a year which has seen him playing his part to save Bukit Brown. Zheng Han is a 3rd year student, currently studying English and History at NTU/NIE.

Reflection

On the morning of 31st March 2012, three days before the actual day of Cheng Beng on 4th April my family and I headed to Track 14 (Old Choa Chu Kang Road) to the Hokkien Cemetery and Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery to pay respect to our ancestors. It had rained nonstop the night before. The poem 淸明- 杜牧 (唐著名詩人), captured the mood of the day, perfectly.

I only remember tagging along with the family for Cheng Beng about five years ago. I did not know why I wanted to go then. Maybe I thought it would be somewhat of an adventure to be climbing up the hills to visit my ancestors.

Recently, many Singaporeans including me have been trying to save Bukit Brown Cemetery from an 8 lane highway because we feel it is an intrinsic part of our nation’s history, heritage and habitat. Although I do not have any ancestors buried at Bukit Brown, it spurred me to find out more about my country and my ancestors. Personally, I feel that it is only by being able to find out about my country’s and ancestor’s histories that I am able to understand more about Singapore and myself. Cheng Beng offered me a chance to reflect upon this, to help me connect the past to the present and future; it reminds me that Singapore is home from the very day my great grandfather decided to make this place his home.

Family History (paternal)

This year, I decided to write this short reflection and take my camera to snap shot my family’s past. I have always wondered how my ancestors made the long and difficult journey out of their village many kilometers inland of Quanzhou, Fujian to Singapore without modern transportation such as cars, trains or planes. Instead they traveled the arduous journey by a boat all the way to Singapore. I guess I will never be able to find out or fully understand how it feels to leave home and make a new life for myself in a strange land. But I feel fortunate because my ancestor took that journey and I came to be born here.

My paternal great grandfather passed away about 20 years after arriving in Singapore a few years before the Japanese Occupation of Singapore. My father never knew him. Of my paternal great grandmother (his grandmother), he has only very vague memories as she passed away in the mid 50s a few years after he was born.

My father recalls life was tough growing up. He was one of 10 children and his parents – my grandparents – eked out a living raising poultry and pigs, and growing vegetables. Meals consisted mostly of porridge with soy sauce and some vegetables, and only occasionally a treat of meat. I have wondered how it would have felt to eat this meager meal day in and day out. But I am also guilty of complaining at times when my father cooks and I ask ‘Why is it the same thing again?”

It has only been in recent years that I felt a compulsion, a hunger to find out more about my family’s past and by extension to get a sense of my country’s past. Of course I realised I am no longer able to ask or hear stories from my grandparents who both passed away more than 10 years ago. I had not realised how much my grandparents doted on me when I was a child. But I am not about to let this deter me as I turn to my Ah pek (阿伯/ uncle), Ah kor (阿姑/ auntie) and the extended family to find out about my history, my story.

Cheng Beng 2012

1st Stop – Paternal great grandfather up the hill @ Track 14 Hokkien Cemetery

On top of a hill the simple pre- war grave of my paternal great grandfather, made almost entirely of bricks

The five-coloured paper represents the 5 cardinal directions and signifies that the grave has been visited. Some people choose to put the paper in the form of a flower for both aesthetic and pragmatic purposes, as paper can't be blown away by the wind

Some vegetables growing out of a grave about 3 metres away from my great grandfather’s grave

First up, offerings for the Earth Diety consisting of tea, sweets and biscuits together with the incense, special candles and joss paper that my uncle is burning. 3 incense sticks at anyone time

2nd Stop – Paternal great grandmother mid-hill @ Track 14 Hokkien Cemetery

Shock when we reached great grandmother’s place. The heavy downpour throughout the night caused some flooding, or ‘im chwee’ in Hokkien. The flood was cleared by two of my Ah Peks later.

"Huat Kueh"on the headstone of my great grandmother together with red coloured paper taken from the stack of 5 coloured paper. Some use any stone or bricks in place of the Huat Kueh

Great grandmother till clear more than half a century later. No renovating done. You can also see the company that built her grave

2 sons and 7 grandsons listed. In the old days, many graves did not have names of daughters and granddaughters listed.

Final picture with my great grandmother before we left for Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery. Notice the moat that prevents water from accumulating and which directs and channels water downhill. There was some flooding earlier, because of soil and debris that had choked the exit of the grave.

3rd Stop – Paternal grandfather @ Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery

My grandfather’s grave. I noted the difference between the size of a new grave and the old graves earlier.

Incense paper, gold, silver etc for my grandfather. Notice the circle and dot in the middle? It ensures that this gets sent to only my Ah Kong. Just like how a crossed cheque works

4th Stop – Paternal grandmother @ Chua Chu Kang Chinese Cemetery

Quiet moment for my dad with his late mother. Last stop of the day before we went with my Ah Peks (uncle) and Ah Kor (aunties) to have dinner

Favourite drink (Milo) of my grandmother or Ah Mah as I address her in Hokkien. She also likes to eat kuehs like Kueh Bulu and cakes like Pandan Cake. It was only recently that I heard stories from my mother that my late Ah Mah (as a 70 year old lady) used to take a bus alone all the way from Changi to my maternal grandmother’s house at Joo Chiat to visit me when I was a child. Gamsia Ah Mah. Gamsia (Thank you)Mama

Lost in a sea of graves - a failed attempt to locate my maternal great grandfather who passed away in the late 1970s.

Postscript:

I wish to emphasize that every one of us needs to treasure the time we have with our loved ones and not wait until Cheng Beng to do so. While Cheng Beng gives us a formal occasion for the extended family to gather and reminisce about the past, what is even more important is the need to also enjoy the present and love your parents. Treasure the past, and enjoy the present – so that we can eventually embrace the future.

Peranakans in Mourning by Norman Cho

The three most important events in one’s life is thought to be Birth, Marriage and Death. They are seminal. Therefore, the Chinese conceived special rites and rituals associated with each of these occasions.

Traditionally, when death occurred in a Peranakan home, white masking tapes would mark an “X” over the jee-hoe(family plaque) that was hung above the main door as a sign that the residence was in mourning. The main door and the front windows were similarly demarcated. All mirrors in the house were either covered with white cloths or be “X” over with white masking tapes. This was done to prevent deflecting the soul of the recently deceased. If two deaths occurred in a family consecutively, mourning favoured the latest death.

If the deceased had his funeral done away from his own home then a chye kee (red banner/bunting) must be hung at the main door of the residence that hosted the wake. This was to show that nobody from that house had died.

The full duration of the mourning period was three years. This is known as tua-har berat (heavy mourning). It is divided into stages. For the first 100 days, the mourners would wear traditional Chinese mourning garb that was made from belachu (sackcloth material). The womenfolk who would normally don the chignon had to let down their hair as an expression of grieve. The subsequent one year, the mourners would wear fully black baju and sarong (nyonya attire). The nyonya would start doing her chignon during the “black” mourning stage. The following stages would be one year of chit-itam (black-white combination), then six months biru (blue) and the final six months of ijoh (green). Interestingly, each stage is not customarily carried through to the full term for each stage. The mourners would perhaps mourn only 90 days out of the 100 days or 11 months out of the one year.

During the various stages of mourning, the nyonyas would adorn themselves with pearl mourning jewellery set in silver. The whiteness of pearl and silver was thought to be apt for mourning. In the Victorian west, pearl mourning jewellery was also very popular and the pearls signified droplets of tears. It was little wonder that the nyonyas who were under British adopted the same practice. Such pearl jewellery was not only worn by the mourners but also interned with the deceased. It was known that some living nyonyas would commission replicas of their favourite gold diamond jewellery in silver and pearl, to be worn when they depart.

The working male normally wore traditional sackcloth mourning attire till the body was interned. Then, they would switch to wearing a small square patch (made from sackcloth) on the shirt sleeve for 100 days. If the deceased was male, the patch would be worn on the left arm. However, if the deceased was female, the patch would be worn on the right. Subsequently, they would wear a black arm-band for one year, in accordance with the western practice.

When the nyonyas buang/bukak/lepas tua-har (terminates her mourning), she would signify this by wearing bright coloured attire such as red and insert bunga siantan (ixora) onto her chignon. The end of mourning is marked by a definitive splash of colour.

This Sunday, we conquer Hill 4, not quite as indomitable as you think. A leisurely stroll of between 15-20 minutes from the Cemetery gates will take you to Hill 4 . Chat with with volunteer guides: Peter and Catherine, as they take you there, to open minds and hearts. Hill 4 is not on the usual tour but it offers the life and times of the poet and revolutionary who coined an early name of Singapore, “Sin Chew”, features a circus family, a family of 5 cats, a small brigade of sikh guards life- sized and hobbit sized, and the illustrious of Chong Pang, Nee Soon, Tan Tock Seng to name but a few. There are graves here which are also staked and slated to make way for the 8 lane highway which will slice Bukit Brown into half.

Date: 3 June Sunday

Time: 9am to 12pm

Meeting Place: Under the large and beautiful, and possibly endangered, rain tree, at the Roundabout. After the main gate, go forward another twenty metres, to the right of the SLA office

For information on how to get there and handy tips please visit

http://bukitbrown.com/

==========================

Registration:

Our weekend public tours are FREE …

Optimally the group size is 30 participants (15 individuals/guide).

Please click ‘Join’ on the FB event page to let us know you are coming, how many pax are turning up, or just meet us at the starting point at 9am. We meet there rain or shine.

==========================

The Bukit Brown area is about 233 hectares in extent, bordered by Lornie Road, Thomson Road and the Pan-Island Expressway. It lies just to the south of the Central Catchment Forest, being separated from it by Lornie Road and includes Singapore’s only Chinese Municipal Cemetery. With more than 1

Don’t forget to bask in the peaceful surrounds, and also chat with your guides and make friends with other participants. We are amateurs and volunteers, but we are passionate and serious about what we do at Bukit Brown, and we encourage sharing of knowledge.

Here is a map of the grounds:

http://bukitbrown.com/

We will not cover Ong Sam Leong’s (the largest tomb), nor will we visit Chew Geok Leong (with the coloured Sikh Guards). However, if there is time and repeat visitors who already know the way, they could show you how to get there.

==========================

Please take note:

1. We will be walking mainly on paved roads. But there are hill treks so dress appropriately, especially your footwear.

2. Wear light breathable clothing. Long pants and long sleeves if you are prone to insect bites or sunburn. Bring sun block and natural insect repellent.

3. Wear comfortable non-slip shoes, as safety is important. Walking sticks are recommended.

4. Do read up on Bukit Brown before going so you have a better understanding of the place (e.g. BukitBrown.com)

5. Do bring water, light snacks, poncho/umbrella, sunhat and waterproof your electronics.

6. A towel around your neck is a necessary fashion statement at Bukit Brown.

7. Please go to the toilet before coming. There are NO facilities anywhere there or nearby.

==========================

How to get there by MRT / Bus:

Bus services available: 52, 74, 93, 157, 165, 852, 855.

From North: Go to Marymount MRT and walk to bus stop #53019 along Upper Thomson Road. Take Buses 52, 74, 165, 852, 855

Alight 6 stops later at bus stop, #41149, opposite Singapore Island Country Club (SICC), Adam Road. Walk towards Sime Road in the direction of Kheam Hock Road until you see Lorong Halwa.

From South: Go to Botanic Gardens MRT and walk to bus stop #41121 at Adam Road, in front of Singapore Bible College. Take Buses 74, 93, 157, 165, 852, 855. Alight 2 stops later at bus stop, #41141, just before Singapore Island Country Club (SICC), Adam Road. Cross the bridge, walk towards Sime Road; follow the road until you see Lorong Halwa.

By car:

Turn in from Lornie Road, to Sime Road. Then, turn left into Lorong Halwa.

Parking space available at the largish paved area near the cemetery gates.

By a strange coincidence, different forms of mosaic art flourished in the West and East independently of each other. The renowned Byzantine mosaics have their parallels in the “jian nian (剪黏)” or cut and paste mosaic sculptures of Southern China. This decorative technique is widely used in traditional architecture, particularly in the elaborate sculptures adorning the roofs of temples in the Fujian and Chaozhou regions. Migrants from these regions brought the technique abroad and mosaic sculptures can be seen in many traditional buildings in Singapore and Malaysia.

A cemetery is not the usual place to find an ornate temple roof but the art of “jian nian” has nevertheless managed to find its way into Bukit Brown. On Hill 4, at the tomb of Mdm Yeoh Siew Kheng (commonly known as the “5 cats” tomb due to the presence of 5 lions), a lavish display of “jian nian” mosaics can be seen. There are the five lions, a pair of male attendants and tableaux featuring the 8 immortals. Even the Chinese characters of the tomb couplets are mosaics.

Time and the elements have not been kind to these art pieces but enough remain to give a hint of the once gay colours and resplendent forms.

So far, this is the only instance of “jian nian” mosaic sculptures found in Bukit Brown. With so many tombs unexplored there may be more surprises in store.

The search for a long lost aunt buried at Bukit Brown began last year, when Miho Tan requested the help of Raymond and Charles Goh to locate his father’s sister. She provided these details

Name : Tan Lay Chee

Grave : C III, 857

Age : 18

Year of death : December 1932

Following up this year, Raymond found Miho’s aunt and from her tomb inscription discerned that Tan Lay Chee died at the young age of 17 on Christmas Day, 1932. She was unmarried, but a boy was inscribed in the tomb as a “stepson”. According to the information Raymond gathered – the burial registry does record cause of death – she died of mo tan, a kind of high fever.

He recalls her family visiting her tomb a few years ago but they had forgotten the route as the surrounds had become quite inaccessible due to fallen trees and overgrowth.

The family of Tan Lay Chee visited her soon after Raymond located her tomb, and brother Lay Chee connected once more with his elder sister.

Also buried at Bukit Brown, is Miho’s grandfather. Miho captured a family visit to his tomb in February in a video here

Grandfather Tan Choon Kiat was a book keeper and died at the relatively young age of 51 years old.

Miho’s grandmother, Lim Geok Yan survived her husband by more than 30 years. She died just past her 80th birthday and her ashes are interred at Bright Hill Temple at Sin Ming. Her grandfather’s tomb, is a double tomb but he rests alone. It can be deduced that his wife was originally intended to rest side by side with him.

The life and times of Lim Geok Yan is deeply etched in the mind of Miho’s father. He was the youngest of 8 children, 6 boys and 2 girls. We know she had to bury a child and as a young widow life must have been tough. Miho recalls what his father shared with him:

“Being a tough nonya my Dad says she had to pawn her jewellery bit by bit in order to maintain the household , the daily expense had to cover (they lived in a traditional Peranankan house), around 16 members which included 7 “cha bor kan” – Hokkien for maids. She was a strict mother too (Dad did not elaborate). I’m sure she would have been been a strict grandmother too and maybe I’ll be allowed to wear traditional Baba wear on special days.”

Miho remembers being taken to the Baba House, where her father pointed to a portrait of Lim Ho Puan hanging there, and he said to Miho, “there, that is your chor kong – (Hokkien for great grandfather)”

Lim Ho Puan is among a list of luminaries which include Lim Boon Keng, Lim Nee Soon and Lim Yew Hock named in the book Singapore Chinese Society in Transition, Business, Politics and Socio Economic Change, 1945 – 1967

A simple tomb of a long lost aunt, has become for the niece who never knew her, a touch stone revealing a family history which is both personal and historical.

几枚白石伴青珉,

小筑坟莹隔岁春

地下有灵相谅解,

迟工原是为家贫.

A few pieces of white rock accompany the green stone,

A little grave built but alas late one year

My dear I hope you can understand the reason,

I am late to build because of my poverty.

(Khoo Seok Wan (1874-1941) in memory of his wife, Lu Jie (陆结)

He was a Confucian scholar, a political activist in revolutionary China, a prominent community leader in Singapore and an early advocate for education for girls who helped set up the Singapore Chinese Girls School.

Born into a wealthy merchant family, Khoo’s fortunes waxed and waned because of his extravagant life style ( he was known to be a generous host) and the over extension of his funding activities to revolutionary causes. But embedded in his life is a love story which captured the heart of Bukit Brown resident tomb whisperer Raymond Goh; he was determined to find his grave.

When Khoo Seok Wan’s wife died in 1936 at the age of 44, his fortunes were on the wane and he was bankrupted. He could not afford a tombstone for his wife whom he buried in Bukit Brown. So he buried his own tooth with her and when he could afford it the next year also constructed his own tombstone in preparation to be reunited her one day. The poem was penned to mark the occasion.

Khoo was born in Fujian, China, and followed his mother to Macau before he joined his father in Singapore in 1881. His father, Khoo Cheng Tiong (邱正忠), was a successful rice merchant and prominent community leader in Singapore. Khoo was schooled in traditional Confucian education, and when he was 15 years old, he went back to his hometown to prepare for the Chinese imperial examinations. He passed the district and provincial examinations to attain the level of a juren (举人) that qualified him as a candidate for the central government imperial examinations in Beijing, but he failed in that attempt in 1895 and returned to Singapore.

Khoo suffered from leprosy and lived his last years on the generosity of his friends. He died in Singapore at the age of 68 on 1 December 1941.

He was buried in Bukit Brown cemetery beside his wife. Earlier this year, Raymond Goh finally tracked down the tombstone Khoo built for himself and his wife from records in the Burial Register lodged with the National Archives. Khoo Seok Wan’s tomb is in Blk 4 Section C, is in the path of new dual 4 lane road.

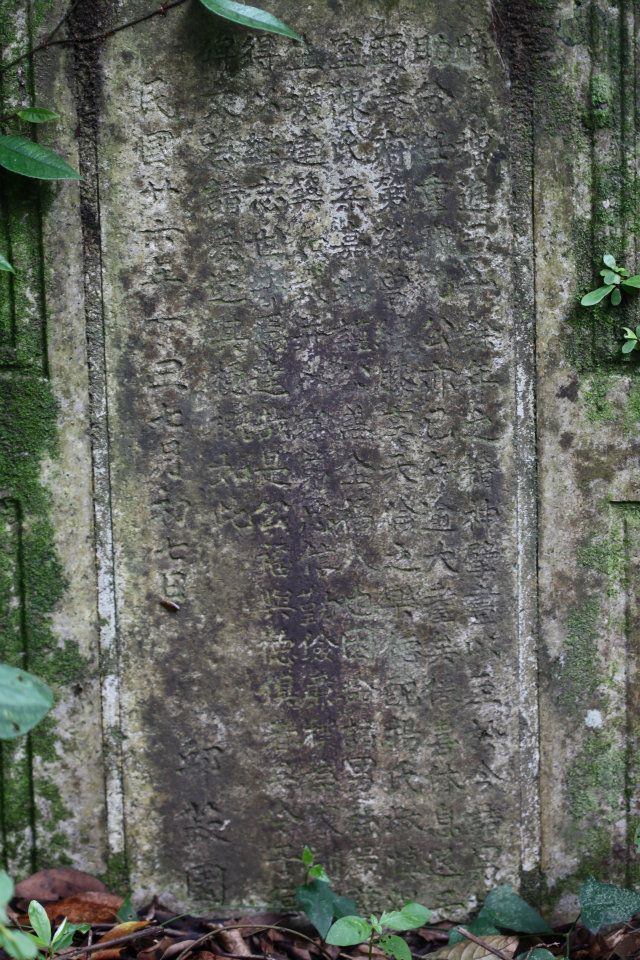

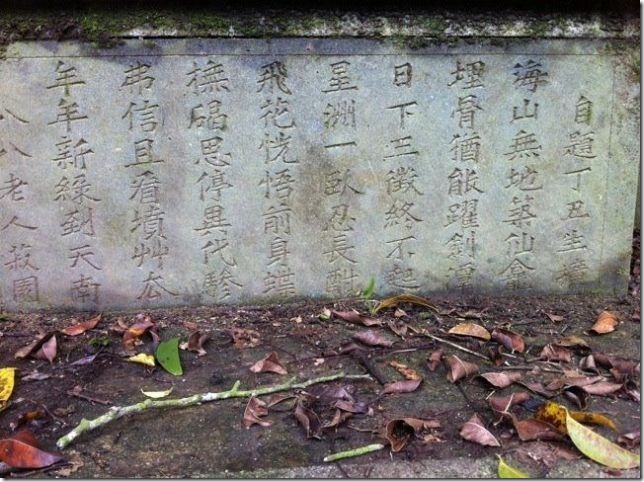

Khoo Seok Wan “live” tomb, inscribed on the altar is his epithet which he penned himself (photo:Raymond Goh)

海山無地築仙龛

… How can the buried bones leap across the sword lake

日下三徵終不起

Even if you beckon 3 times, I could no longer arise

That lay in Singapore enduring long thirst

Flying flowers realized their butterfly past life

Caressing the epigraph, thoughts stop and future generations

If you don’t believe just look at the tomb grass

88 old man Seok Wan

I stand before him, silent, in respect and awe.

His genes embedded in every cell of mine

We are bonded though the course of time.

A white stake declares a foreboding future

His eyeless sockets shedding copious tears

That eight lane highway: unspoken fears

“Could you not ask them to let us rest in peace”

His silenced tongue in eloquence loudly says

His bony hands grasp me in one last fond embrace.

by Lim Su Min 林蘇民 in tribute.

The prolific Khoo is responsible for composing epithets for luminaries buried at Bukit Brown. Among them the father of Khoo Teck Puat, Khoo Yang Thin. His epithet is an exhortation to the descendents through a list of things to do to live a good, honest and honorable life.

Discernible beneath the grime there is true grit Khoo Yang Thin’s grave can be found in group 12 on the map (photo Perry Tan)

Another example is the epithet for Wee Teck Seng’s tomb (just below Gan Eng Seng):

Khoo Seok Wan was also responsible for popularizing the term Sin Chew which is a sobriquet for “Singapore” (translated) Khoo writes: Singapore is an island surrounded by the sea, and with vessels and boats large and small anchored around it; the glitter of artificial lights at night are like a crown of illuminated stars (“星”) when viewed from afar. “洲” (zhou, island) and “舟” (zhou, boat) are homonyms: while the boat lights are like stars, those on the island are like the Big Dipper to accentuate the constellation. This is why the term “Sin Chew” is widely known by folks here and afar.

Editor’s note: In the first posting of this article, Lim Su Min our tea master, believed Khoo Seok Wan to be his great great grandfather based on initial evidence. Further investigation has shown this trail to be false. But in the spirit of paying tribute to Khoo Seok Wan the poet, we are leaving in this post the poem composed by Su Min.

New activity for this Sunday, Eco Stations with Beng Chiak of Nature Society, hunt down ants and insects and understand their relationship to plants and trees, how trees host other living things and nature’s self help system! Check out more details here

Family Day, we did it last Sunday on March 11 and we now know we can do it even better. Up sized buffet of activities from guided tours to treasure hunts, to arts and crafts, haiku composing for all ages and nature gems for the whole family. Adults must be accompanied by children for treasure hunts!

Please read handy tips for a more enjoyable day, there will be a quiz before you can join – just kidding – but do, DO read it for safety precautions!

The event begins at 9 am and will end by 12.30 pm.

Tours will be done differently, instead of one long guided tour, there will be 4 stations to stopover and participants may drop out anytime they want to sample other delights. Student volunteers will usher participants from station to station in 2 rounds of tours one starting at 9 am and the second at 9.30 am. They will also point out directions to those who want to return to the roundabout.

Please download this map and take note that the 4 stations covered in the route are group 1, group 3, group 4 and group 12. Constraint by time guides may not be able to cover every tomb in each group. The estimated schedule if you visit every station is 2 hours. This is the timetable with estimated times and guides :

9.oo at Sikh Station – introduction by Catherine (Second tour starts at 9.30 am if there are more than 10 people and follows the same schedule as tour 1)

a)9.15 at group 1 – by Peter (second tour eta 9.45)

b)9.50 at group 3 – by Raymond (second tour eta 10.20)

c).10.30 at group 2 – by Yik Han (second tour 11.00)

d) 11.10 at group 12 – by Charles, this last station will be capped by a short uphill (easy) to the jewel in crown Ong Sam Leong’s family grave site and group photo. ( the second tour eta 11.50 will be led Catherine and Peter )

This gives you some idea what some of your guides look like:

For the treasure hunts starting at 9.30am, look out for :

Your Emeritus Zoo Keeper of Bukit Brown – She is responsible for collecting “animals” for the treasure hunt and the design.

Watch this space for more details of Family Day activities by co-organisers: SOS Bukit Brown and Nature Society, Singapore

Dateline 4 March Sunday 2012, Raymond Goh after a grueling morning tour which stretched 3 hours, returns to Bukit Brown after lunch and scored a hat trick which helped connect relatives to their ancestors.

Tomb 1-

The family of a certain Mdm Fong Fon who died during the war. They family had contacted LTA who then advised them to contact me. They emailed me previously but I had not time to reply. So I decided to search for her the day before and found it, and today (Sunday) I saw them looking for graves at Blk 4 with some tomb keepers., Out of curiosity I approached them. They were looking for plot number 20. Bingo! It was the same tomb belonging to the same family who had emailed me. The plot number was indeed 205, but it was at Blk 3 Section .

Tomb 2 –

I was coming down from the Gan Eng Seng tomb when I encountered 3 people looking for their grandfather’s tomb. They had never been to their grandfather’s tomb but recalled their father telling them it was somewhere up a hill. They managed to obtain the tomb number from the burial register, it was Blk 3 Section B tomb 389. He was a certain Mr Ng who hailed from Tong Ann. I led them quite high up the steep hill, and when they saw their grandfather’s tomb they apologized to him for not visiting for a long time. They then informed him that if it had not been for a volunteer to guide them, (yours truly) they would never have found him, and they thanked the stars for this wonderful reunion.

Tomb 3 –

This was the third attempt of a request to locate the grave of a 17 year old woman Tan Lay Chee who died in 1932. Although the tomb address is Blk 3, Section C, 857, it was actually located at the very top of the hill, some where in Section B. I think for all of us, each and every tomb in Bukit Brown is precious, whether big or small, poor or rich, for it means something special to someone out there. It was third time lucky as they say, but sometimes the spirit of Bukit Brown works in mysterious ways and my last tomb find of the day, enriched me greatly at the end of a long day.

text and photos by Raymond Goh

This letter was penned for ST Forum to be considered for publishing.

Letter reads:

The commentary by Chua Lee Hoong (“Resilience and the curse of narcissism” ST March 1, Budget Debate 2012) on NMP Faizah Jamal’s maiden speech goes to the heart of a question which has been elusive: What is it that we love about Singapore which roots us to our country. The answer simply put by the new NMP is land.

There is a piece of land called Bukit Brown Cemetery through which a new highway is scheduled to be built in 2013. It will slice through some of the most beautiful landscapes still available and accessible, and destroy it forever. It is also slated a couple of decades down the road for housing.

Bukit Brown Cemetery is approximately 97 acres, and has for over 100 years been landscaped by nature; it is also a piece of land that tells the story of our nation.

The tomb of Fang Shan, a coolie from China is recorded as the oldest remains of an immigrant interred at Bukit Brown. He died in 1833, 14 years after the founding of Singapore.

So far, 25 pioneers for whom our streets are named have been “discovered” at Bukit Brown; at last count some 15 pioneers who supported Sun Yat Sen’s revolution have also been identified.

Bukit Brown is the site of a fierce battle on 14 February 1942 between the British and Japanese. We are marking the 70th anniversary of The Battle of Singapore this year. A war archaeologist believes Bukit Brown is one of the last remaining battle fields intact from the theatre of war in the region. During the war, the cemetery was also the site of group burials for civilian casualties of all races.

Early this year, a small group of volunteers who have come to love this piece of land, started guided tours on request from various groups and the public, to share what little we have learned about its history and habitat.

I conducted a tour for a group of 16 year old students who had asked their teacher if she could arrange a visit. The site visit was followed up in the classroom when they invited an Assistant Professor to talk to them about the people buried there particularly, from their alma mater.

I ended the site tour at the crossroads in Bukit Brown, shaded by a canopy of rain trees, where there is ironically a no entry sign. I left the boys with this thought: 10 years down the road they may find themselves in an office looking at plans for Bukit Brown. 20 years down the road they could also be living here. What would they choose?

Bukit Brown holds the promise of land, as defined by Faizah Jamal. It should be protected in its entirety as a legacy for future generations, for them to decide what their legacy will be.

By Catherine Lim

Recent Comments